| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

| 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station | 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station |

| 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

| 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

The Greatest and Most Important Time in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS | LITANIES FOR PASSIONTIDE |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | The Last Days of Christ | Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

CLICK ON ANY LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS | LITANIES FOR PASSIONTIDE |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | The Last Days of Christ | Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

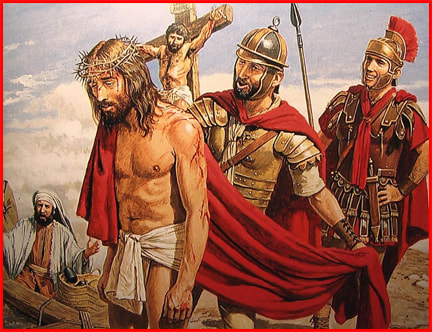

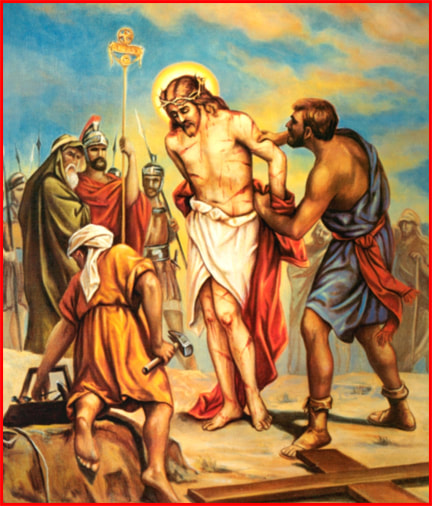

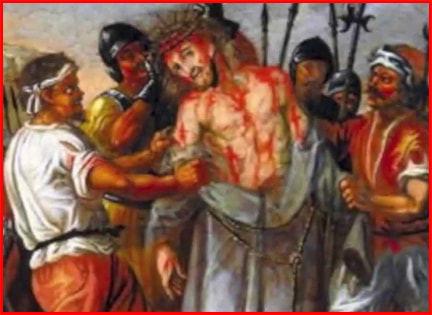

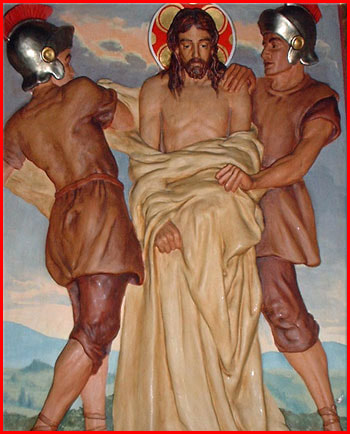

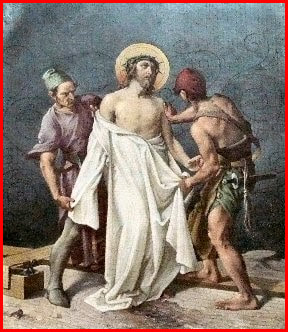

THE TENTH STATION : JESUS IS STRIPPED OF HIS GARMENTS

“St. Augustine assures us that there is no spiritual exercise more fruitful or more useful than the frequent reflection on the sufferings of Our Lord. St. Albert the Great, who had St. Thomas Aquinas as his student, learned in a revelation that by simply thinking of or meditating on the Passion of Jesus Christ, a Christian gains more merit than if he had fasted on bread and water every Friday for a year, or had beaten himself with the discipline once a week till blood flowed, or had recited the whole Book of Psalms every day” (The Secret of the Rosary, St. Louis Marie de Montfort, “Twenty-Eighth Rose”).

|

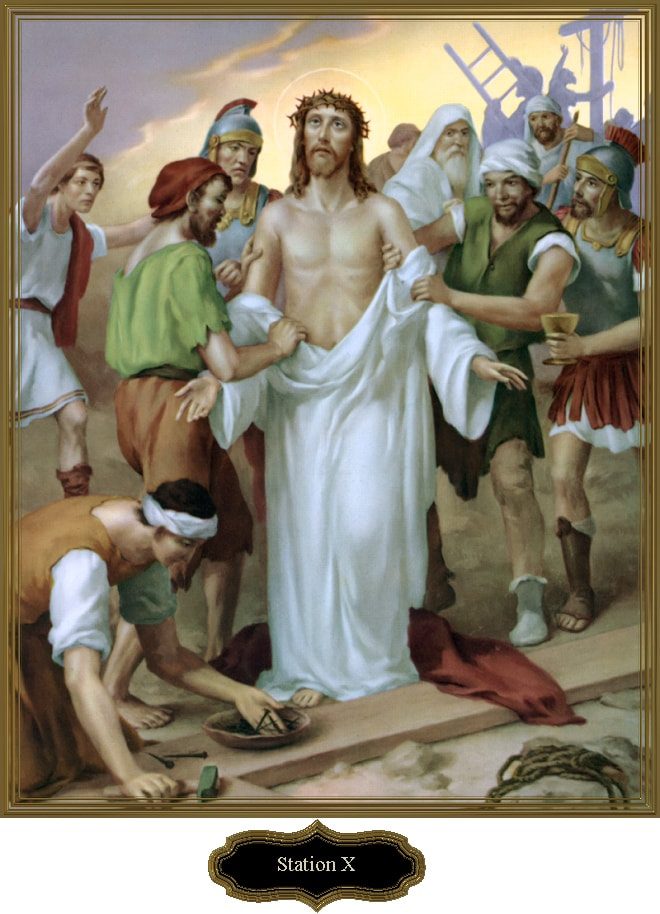

The following passage is taken from The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ by Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich

The preparations for the crucifixion being finished, four archers went to the cave where they had confined Our Lord and dragged Him out with their usual brutality, while the mob looked on and made use of insulting language, and the Roman soldiers regarded all with indifference, and thought of nothing but maintaining order. When Jesus was again brought forth, the holy women gave a man some money, and begged him to pay the archers anything they might demand if they would allow Jesus to drink the wine which Veronica had prepared; but the cruel executioners, instead of giving it to Jesus, drank it themselves. They had brought two vases with them, one of which contained vinegar and gall, and the other a mixture which looked like wine mixed with myrrh and absinthe; they offered a glass of the latter to Our Lord, which He tasted, but would not drink. The executioners soon pulled off Our Lord’s cloak, the belt to which the ropes were fastened, and His own belt, when they found it was impossible to drag the woolen garment, which His Mother had woven for Him, over His head, on account of the crown of thorns; so they tore off this most painful crown, thus reopening every wound, and seizing the garment, tore it mercilessly over His bleeding and wounded head. Our dear Lord and Savior then stood before His cruel enemies, stripped of all, except the short scapular which was on His shoulders, and the linen which girded His loins. His scapular was of wool; the wool had stuck to the wounds, and indescribable was the agony of pain He suffered when they pulled it roughly off. He shook like the aspen as he stood before them, for He was so weakened, from suffering and loss of blood, that He could not support Himself for more than a few moments; He was covered with open wounds, and His shoulders and back were torn to the bone by the dreadful scourging He had endured. He was about to fall when the executioners, fearing that He might die, and thus deprive them of the barbarous pleasure of crucifying Him, led Him to a large stone and placed Him roughly down upon it, but no sooner was He seated than they aggravated His sufferings by putting the crown of thorns again upon His head. MEDITATION Let God strip away all your undue attachments There is one detachment that we bring about, and there is another that God brings about for us. The Christian who is trying to follow Christ on the way to Calvary does not confine his detachment to what he gives up; he thinks of detachment more from the point of view of what God takes. A religious man can become so deeply interested in the process of detaching himself from this and that—in drawing up his list of things to be shed — that he forgets what detachment is primarily for. So long as I say, “Lord, look with favor upon these renunciations I am making for You,” I have one eye on the generosity of my sacrifice. When I say, “Lord, I tend to cling so tenaciously to the things I like that the best plan would be for You to detach me in Your own way by taking whatever You want,” I have my eyes on God. It is a fairly general rule that wherever there is less glamour, there is more room for grace, and there is far less glamour in allowing God to take than in making self-chosen sacrifices. But it is a doctrine that has to be properly understood. A man has no right to conclude that because he has nominally given God a free hand, he can dispense himself from ever making a sacrifice. Far from providing a good excuse for indulgence, the principle of letting God take supposes an overall declaration against indulgence. On the assumption that a measure of renunciation is recognized by the soul as absolutely necessary, it is suggested here that the grace of detachment comes more readily when the emphasis is on God’s action rather than on our own. Detachment is a grace, but not necessarily a miracle. There has to be the will to detachment, and even the actual striving after detachment, before God grants the supernatural habit of detachment. We are inclined to make the mistake, when thinking about the relation between the gift and the use of the gift, of imagining that the reward comes first and that the virtue comes after — as one who would say, “I can wait for the grace of continence before I need to try to be continent.” While we have every reason to trust in grace rather than in any strength of our own, we have no reason to trust in grace as though it were magic. Leaving aside the man whose laziness is supported by superstition, who persuades himself that one day there will be a click in his mind and he will thenceforth be able to float his way to God, unencumbered by creatures, we can consider the alternative methods employed by two men who are seriously bent upon perfection. Both men hear Christ’s summons to launch out into the deep (Luke 5:4). Both survey their respective crafts, and to each it must appear that his boat is overloaded for the task. One man says, “If I am heading for deep waters, I must take no risks. I shall have to throw overboard my cigarettes, my sherry, my spare clothes, my books, my pictures, my camera, and my television set. It is the price I have to pay, and, after all, I am doing it for God.” The other man says: “I hate getting rid of anything. When it comes to choosing, I do not know what I am meant to keep and what I am meant to throw away. If I am heading for deep waters, I must take no risks. I dare not throw away something that may be necessary to me when the voyage gets under way. I dare not risk having to come back to pick up what I had stupidly judged to be ballast. I must put my confidence in God, and let Him arrange the journey for me. It is He who has called me to do this thing, so I can believe that He will either wash overboard what is excessive weight or else give me the judgment to make these practical decisions as I go along.” Whereas the first man is liable to alternate moods of dismay and vainglory, the second is made constantly aware of God’s Providence and of his own insufficiency. Whereas the first, devising an approach that may or may not be in the plan of God, limits the idea of renunciation to a particular area, the second gives unconditional scope to the divine action. The one looks at his boat more than at God; the other looks at God more than at his boat. It was Christ’s will that all His life He would do without luxury and even comfort. Unlike the foxes with their lairs and the birds with their nests, the Son of Man had nowhere to rest His head (Luke 9:58). He who owned all ― to whom every inch owed rent — willed to have no place of His own. Detaching Himself from what belonged to Him, he lived for the love of the Father as a poor man. Not only did He choose to be without this and that, but He chose to let others take from Him what they wanted. He submitted to being stripped of even those things which were for His necessary use. The Tenth Station shows us the extreme to which Christ’s love of detachment took Him. While many of those who aspire to the Christ-life will be deprived of their comforts, few will so nearly resemble Christ as to be deprived of their covering. But in spite of the gulf that exists between Christ’s example in this matter of detachment and our own practice, there is occasion here for self-examination. Am I detached enough about dress, or do I set too much store by being comfortably or fashionably or expensively or strikingly clothed? Am I resentful when people take away my things and wear them? I must remember that while the lilies of the field are better dressed than Solomon (Matthew 6:28-29), Christ had not the comfort of being as properly clothed as the plants He had created. If we are to be detached from soft living and all that pleases the senses, we are to be detached all the more from pleasures and possessions that touch us more closely. The pleasures of friendship, for example, are to be held in a loose grasp. A good friend is as legitimate a possession as a good suit, but the follower of Christ should be as ready to be stripped of the one as of the other. The man whose affections cause him to snatch at the response that he looks for in others, that cause him to cling to the time or the confidence or the exclusive love of another, has not understood the meaning of detachment. The more subtle the pleasure, the greater is the need for detachment. At the moment when Our Lord was allowing His clothes to be taken from Him, He was allowing His Apostles to leave Him. It is harder to he detached from our followers than from almost anything else. Detachment, if it is to be complete with the completeness of Christ’s, must extend to our good name. A man’s reputation is as legitimate a good as can be had, but even here there can be occasions when the possessor must stand back and show a supernatural indifference toward it. In the approach to Calvary, no prelude to the Crucifixion can be more apt than loss of standing. When the world turns against a man whom it once approved of, when the cry goes up that the hero had clay feet after all, the consummation cannot be far off. But a man has to be far advanced in detachment if he is to bear this trial with equanimity. If without dramatizing it in any way or indulging in the least self-pity, a man can watch the process of his own decline in public favor, and unite the experience to Christ’s at the hands of the Jews, he is blessed indeed. Not many can bear the reversal of a confidence that has been placed in them. Finally, there is the detachment from ourselves. A man may have renounced physical indulgence, may have risen above the intellectual delights of reading and the arts, may have surrendered his following of disciples, and may have sacrificed his reputation for the love of God, but if he is to enjoy the grace of transforming union, he has still to be stripped of his self-esteem. Layer after layer of self has to come off until he knows by the most intimate of all experiences — the experi- ence of truth burning its way into the soul ― that he is nothing and that God is all. He has to stand there and look on while the light of grace exposes one by one his evasions, part-playings, secret refuges, compensations, and self-deceptions. Since there is room for self even in the disgust and humiliation that follow such a revelation — “He who despises himself,” says Nietzsche, “nevertheless esteems himself as a despiser” ― there must be a detachment once again. When full confidence in God has replaced the bitterness of self-knowledge, then can the soul be made ready for the final union. Not without reason do the earliest presentations of this station include in its title the mention of gall. That Christ at His stripping was handed the sourest of all drinks is a detail that implies much (Matthew 27:34). The cup has always been the symbol of suffering, even when we think of it as the chalice of salvation, so we should not be surprised at finding in it vinegar as well as wine. CONCLUDING PRAYER V. We adore Thee, O Christ, and we praise Thee, R.. Because by Thy holy cross Thou hast redeemed the world. O Jesus, strip me of my old sinful self and renew me and rebuild me according to Thy will and desire. I will not spare myself, however painful this should be for me: stripped of all temporal and material things, stripped of my attachments to the persons, places and things of this world; stripped of my own will and preferences; I wish to die to all these, in order to live for Thee forever. PRAYER O Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me! Offer me Thy helping hand, and aid me, that I may not fall again into my former sins. From this very moment, I will earnestly strive to reform: nevermore will I sin! Thou, O sole support of the weak, by Thy grace, without which I can do nothing, strengthen me to carry out faithfully this my resolution. Our Father Hail Mary. Glory Be. V. Lord Jesus, crucified, R. Have mercy on us! |

Web Hosting by Just Host