| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

LINKS FOR ARTICLES IN "THE NARROW PATH TO HEAVEN" SERIES

Preface: Introduction to the Mountain

1. Setting-Up Base Camp

2. To Go Further, or To Go Back Down?

3. The Real Climb Begins

Preface: Introduction to the Mountain

1. Setting-Up Base Camp

2. To Go Further, or To Go Back Down?

3. The Real Climb Begins

PART 2 : TO GO FURTHER? OR TO GO BACK DOWN?

|

Letting the Natural and Physical Give Supernatural and Spiritual Lessons

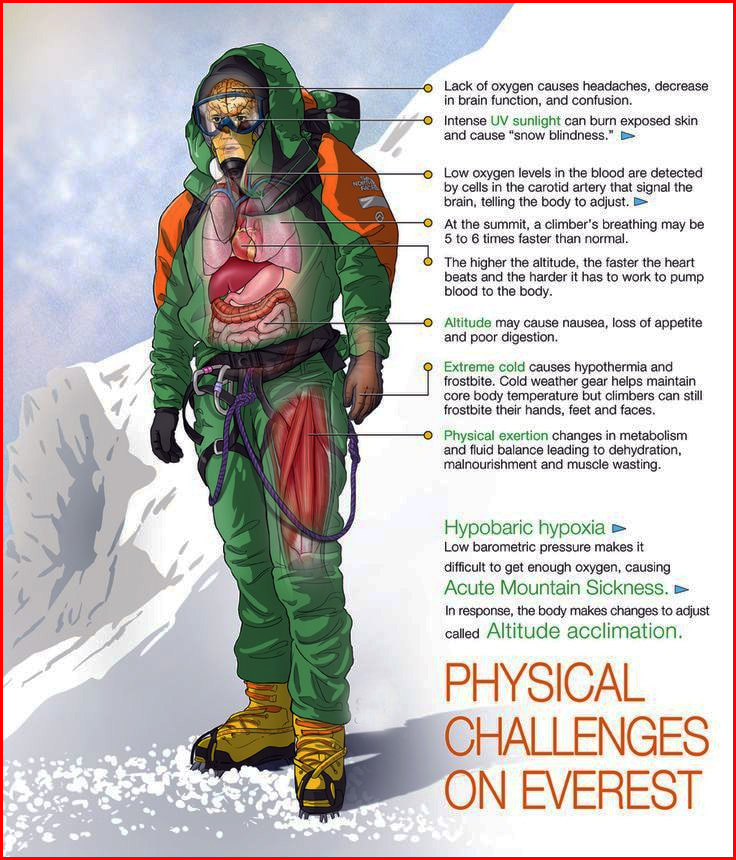

Before we draw spiritual analogies—of which there are an abundance, almost like the snowflakes on Everest—let us examine the natural and material and physical aspects of climbing Mount Everest, before moving into the supernatural and spiritual lessons to drawn and learnt from the experience. Thus, we shall look at a paragraph or two of the natural, and then draw some spiritual fruit from it. [NATURAL] In the preceding articles, we have come from the comforts and lower altitude of the city (Kathmandu) to the discomfort and much higher altitude of Mount Everest Base Camp. Around 30,000 people (in the most recent years) make the trek to Mount Everest Base Camp each year—but trekkers are not climbers. You could compare the trekkers to the spectators at a professional sports game—thousands watch, but only a few play! The many thousands would be incapable of playing the sport—they just prefer to watch from a distance. The same goes for the trekkers to Mount Everest Base Camp—they look at Mount Everest from distance, and rather than climb it, they turn round and go back down to the city. Around 800 people attempt to climb Mount Everest annually. Most who attempt to climb to summit (these days), actually make it—but a large part of that success does not depend upon their skill in climbing, but the quality of trained and qualified climbers who accompany them, like guardian angels and who do most of the hard work for those ‘tourist’ climbers. The percentage of successful summiting has increased recently—largely due to the climb being made easier by many additional safety measures having been put in place on the mountain. More than 4,000 people have scaled the summit since Sir Edmund Hilary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay first conquered the mountain in 1953. [SUPERNATURAL] Only 30,000 people merely come to the foot of Mount Everest each year! Out of a world adult population of around 4,000 million people, only 30,000 come to see it from a distance (at Base Camp) and only 800 seek to go beyond Base Camp and climb Mount Everest each year. Most of the world cares very little about climbing Everest. Most don't have the two months, which it takes, to spare. Many are too old to try. Most are too poor to afford what it costs, and most lack the physical fitness and skill to succeed. The same can be said of the spiritual life and climbing up the ‘mountain’ to Heaven and God. Most of the world cares very little about Heaven. Mos don't have the time to work towards it. Many are too ignorant of how to get there, most make too little effort to get to Heaven. Most do not want to pay the cost of getting to Heaven, and most lack the spiritual, knowledge, fitness, strength and skill to succeed. Death Rate For Everest Summit Climbers [NATURAL] There is no firm count of the exact number of climbers that have died on Mount Everest, but by the end of 2016 about 282 climbers have died, about 6.5 percent of the more than 4,000 climbers who have reached the summit since the first successful ascent by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953. Most climbers die while descending the upper slopes of Mount Everest—often after having reached the summit—in the area above 8,000 meters called the “Death Zone.” The high elevation and corresponding lack of oxygen coupled with extreme temperatures and weather together with some dangerous icefalls that are more active later in the afternoon create a greater risk of death than on the ascent. The sheer number of people that attempt to climb Mount Everest every year also increases the risk factor. More people means the potential for more fatal traffic jams at key sections of the ascent, such as the Hillary Step on the South Col Route or long lines of climbers following in each other footsteps. An analysis of the 212 deaths that happened during the 86-year period from 1921 to 2006 indicates some interesting facts. Most deaths―192―occurred above Base Camp, where the real technical climbing begins. The overall mortality rate was 1.3 percent, with the rate for climbers (mostly non-natives) at 1.6 percent and the rate for Sherpas, natives of the region and usually acclimatized to high elevations, at 1.1 percent. The annual death rate was generally unchanged over the history of climbing on Mount Everest until 2007 ― one death occurs for every ten successful ascents. Since 2007 as traffic on the mountain and the number of tour companies offering climbing packages to anyone with the money and inclination to try it, the death rate has increased. Most commercial expeditions approach Everest’s summit from the Nepalese side, relying heavily on Sherpas to set up camps and transport gear below the South Col. The summit has become the most dangerous place for expedition members—notice how many of them are killed on their way down from the summit to the South Col, and how great the risk of falling is up there. But, arguably, these patterns exist because expeditions members are largely shielded from the mountain’s other dangers—the Khumbu Icefall before “Ice Doctors” (Sherpas) have established safe routes through it with ladders and ropes; the exhaustion of carrying equipment between Base Camp, the Icefall, and higher camps; the repeated, precarious steps over crevasses and under ice shelves during multiple gear shuttles between camps. The Sherpas bear the brunt of these risks.

There has always been a divide between Sherpas and Western summit-seekers, but these tensions have increased in recent years as Everest has become more accessible to unskilled-but-well-heeled climbers. The world’s tallest mountain has become much safer for the average Joe than ever before. For the people who live in its shadow, though, and must return to it again and again to earn a living, the risks haven’t declined in the same way. Susmita Maskey, an expert climber herself, says the burden on Sherpas is intensifying as climbers with little experience increasingly find their way to Mount Everest. “I’ve seen a lot of climbers coming from abroad without training. They don’t have formal mountaineering training and completely rely on the Sherpa guides, putting their life in danger and putting the Sherpa’s life in danger.” [SUPERNATURAL] Likewise in the spiritual sphere and in climbing the mountain of God. There is no doubt about it—today’s Catholics are “dumbed-down” in matters of the Faith, while being “well clued-up” in matters of the world. They have little or no knowledge on what it takes to climb the mountain of God to Heaven, and they have very little training and skill for climbing such a mountain. The losses are heavy! This world has sucked-in and sucked-down so many souls. We are uncomfortable at the thought, much like Fr. Lombardi was uncomfortable, when interviewing Sr. Lucia in 1954, with the thought of many souls being lost in Hell. The interview was printed in the Vatican weekly newspaper, Osservatore della Domenica, on February 7th, 1954. Fr. Lombardi: “Tell me, is the ‘Better World Movement’ a response of the Church to the words spoken to Our Lady?” Sr. Lucia: “Father, there is certainly a great need for this renewal. If it is not done, and taking into account the present development of humanity, only a limited number of the human race will be saved.” Fr. Lombardi: “Do you really believe that many will go to Hell? I hope that God will save the greater part of humanity.” [He had just written a book entitled: Salvation for Those Without Faith] Sr. Lucia: “Father, many will be lost!” Fr. Lombardi: “It is true that the world is full of evil, but there is always a hope of salvation!” Sr. Lucia: “No Father, many will be lost!” Father Lombardi remembered that Sr. Lucia had seen Hell and added: “Her words disturbed me. I returned to Italy with that grave warning impressed on my heart” (Francis Johnston, Fatima—The Great Sign, p. 36). Sr. Lucia was not just giving an isolated opinion of her own creation. She was totally in line with the words of Our Lord, Our Lady and many saints from all the different ages and centuries of the Church—from the time of Our Lord to the present day. Everyone, without exception, is meant and called to climb the mountain of God to Heaven. Yet most never make it—either because they refuse to climb, or they climb without sufficient preparation, training, knowledge and skill.(see more quotes here) To Climb or Not to Climb?—That is the Question! Borrowing a line of thought from William Shakespeare’s play―Hamlet―we shall play upon the words of Hamlet, as he ponders “To be or not to be? That is the question!" In a very broad sense we can apply it to climbing Mount Everest or the mountain of God that stands invitingly and frighteningly before each one of us. We are bidden to climb—yet to climb may lead to death. Yet not to climb will mean eternal death! To die at the foot of the mountain having done or attempted nothing—or to climb and perhaps die in the attempt? A dilemma that Our Lord seems to answer when He says: “For whosoever wants to save his life, shall lose it: and whosoever shall lose his life for My sake and the Gospel, shall save it” (Mark 8:35). First of all, here are Shakespeare’s lines to set the scene, in both old English and modern English: Original Text & Modern English Here is a line-by-line comparison of Shakespeare's words with a paraphrased translation: To be, or not to be: that is the question: To live or not to live, that is the question. Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer Whether it is greater to suffer in your mind The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, All the troubles and nasty things that bad luck throws your way Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, Or to fight against all those troubles And by opposing end them?; By simply putting an end to them once and for all? To die: to sleep no more; and by a sleep to say we end Dying, sleeping—that’s all dying is—a sleep that ends The heartache and the thousand natural shocks The emotional pain and the many stresses That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation that life on earth gives us—to sleep, maybe to dream. Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep; To be sought eagerly. To die, to sleep; To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub; To sleep: maybe to dream: oh, there's the catch; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come For in death’s sleep who knows what kind of dreams might come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, After we have put the noise and commotion of life behind us Must give us pause: there's the respect Must make us stop and think: that’s certainly something to worry about. That makes calamity of so long life; That’s the consideration that makes us stretch out our sufferings so long. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, For who would tolerate the indignities that time brings, The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely, The injustice of the oppressor, the proud man's arrogant rudeness, The pangs of despised love, the law's delay, The pains of unrequited love, the delays of the law, The insolence of office and the spurns The contempt of our superiors, and the rejections That patient merit of the unworthy takes, That happen to those who don't deserve them When he himself might his quietus make When he himself might end it all With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear, With a mere dagger? Who would bear burdens To grunt and sweat under a weary life, To grunt and sweat under a tedious life, But that the dread of something after death, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscover'd country from whose bourn The unknown region from which No traveler returns, puzzles the will No traveler returns, confuses the mind And makes us rather bear those ills we have And makes us prefer to endure the troubles we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Rather than fly to new, undefined troubles? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all; In this way, thinking makes cowards of us all; And thus the native hue of resolution And thus the natural color of decision-making Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, Becomes sickly with the pale color of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment And enterprises of great power and importance With this regard their currents turn awry, At this point are derailed, And lose the name of action―Soft you now! And become inactive. Hey now! The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons The lovely Ophelia! Girl, in your prayers Be all my sins remember'd. May all my sins be remembered. Let Us Dig Beneath the Surface Snow The first six words of the soliloquy establish a balance and a dilemma. There is a direct opposition and contradiction, that is mutually exclusive, for you cannot have both ― “to be, or not to be”―you cannot have your cake and eat it. Hamlet is thinking about life and death and pondering a “state of being” versus a “state of not being” ― being alive and being dead. We could say, in the spiritual domain, “To be alive to God, or dead to God? … To be alive to the world, or dead to the world?” … When could further transpose this onto the spiritual life--“To be spiritually alive in a state of grace, or to be spiritually dead without the state of grace?” … “To be a true Christian, or not to be a true Christian? That is the question!” … “To be of this world, or not to be of this world? That is the question?” … “To be like everyone else, or not to be like everyone else? That is the question!” … “To live for this world, or to live for Heaven? That is the question!” Our Lord answers: “Lay not up to yourselves treasures on Earth… but lay up to yourselves treasures in Heaven … No man can serve two masters. For either he will hate the one, and love the other: or he will sustain the one, and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon … If thou wilt be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come follow Me” [up the mountain] (Matthew 6:19-24; 19:21). What Hamlet is musing on is the comparison between the pain of life, which he sees as inevitable (the sea of troubles - the slings and arrows - the heart-ache - the thousand natural shocks) and the fear of the uncertainty of death and of possible damnation of suicide. Hamlet's dilemma is that, although he is dissatisfied with life and lists its many torments, he is unsure what death may bring (the dread of something after death). He can't be sure what death has in store; it may be sleep, but perhaps that is merely a speculative dream or wishful thinking, and perhaps it is an experience worse than life. Death is called “the undiscover'd country from which no traveler returns.” In saying that, Hamlet is acknowledging that, not only does each living person discover death for themselves, as no one can return from it to describe it, but also that suicide is a one-way ticket. If you get the judgment call wrong, there's no way back. Some may think that ending one’s life, when faced by troubles, is a form of Heaven—but in reality they only find Hell afterwards. For those who suffer hell in this life, the afterlife brings Heaven. Make no mistake about it—climbing the mountain of God, like climbing Mount Everest—can be hell at times, but it is a hell that promises Heaven. To climb or not to climb? That is the question! The whole speech is tinged with the Christian prohibition of suicide, although it isn't mentioned explicitly. Spiritually, we could say suicide is the attempt to end what the Providence of God has chosen as our path up the mountain of God. We refuse it because we think it to be unfair or too difficult. Yet there is a catch—for in refusing what we feel is too difficult, we end up in even grater difficulties. The dread of something after death, would have been well understood by a Tudor audience to mean the fires of Hell. The speech is a subtle and profound examining of what is more crudely expressed in the phrase “out of the frying pan into the fire.” We can very easily try to escape the heat of the frying pan of this world, but in doing so, fall from the frying pan into the fires of Hell (or Purgatory at best). In essence, yes, life is tough and sometimes downright bad, but death and what comes after death might be far worse if we fail to manfully climb the mountain of life to God in Heaven. To put it another way, if you pardon my ‘French’--“If you can’t stand hell on earth, then how the hell will you tolerate hell in Hell?” To climb the mountain of God may be a helluva climb, but it’s a climb that avoids the chasms of Hell and leads to the heights of Heaven. |

Web Hosting by Just Host