| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CHOOSE THE MIRACLE YOU WISH TO READ ABOUT FROM THE LINKS BELOW

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

THE VICTORY OF THE HOLY ROSARY AT LEPANTO

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

PART SIX

THE DAY OF BATTLE & VICTORY

THE DAY OF BATTLE & VICTORY

THE CHRISTIAN FLEET GATHERS TOGETHER IN SICILY

|

|

|

ABOVE: The Straits of Messina, as seen from the south-west tip of Italy, looking south-west across the Straits of Messina at the island of Sicily. The famous Etna volcano can be seen in the distance, covered with snow. The narrowest part of the Straits is only 2 miles wide. At the harbor of Messina, it is about 3 miles wide.

THE MUSLIM TURKISH FLEET AWAITS AT LEPANTO

|

Anchored Safely in the Gulf

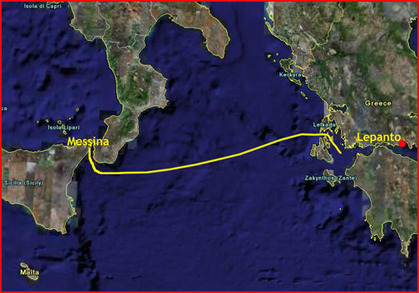

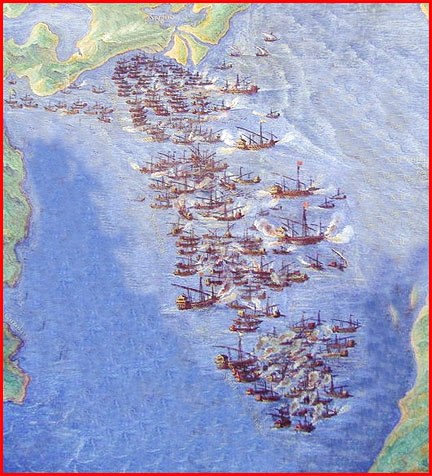

The Gulf of Lepanto is a long arm of the Ionian Sea running from east to west and separating the Pelloponnesian peninsula to the south from the Greek mainland to the north. Jutting headlands divide the Gulf into two portions: the inner one, called the Gulf of Corinth today, ends with the isthmus of the same name, and the outer one is an irregular, funnel-shaped inlet now called the Gulf of Patras. For six weeks Ali Pasha's ships had been anchored inside the fortified harbor of Lepanto located in the gulf's inner portion, and, on October 5th, they began to move slowly westward past the dividing headlands into the outer Gulf of Patras. Still unsure of the enemy's position, Ali Pasha ordered his fleet to drop anchor for the night in a sheltered bay fifteen miles from the entrance to the inlet, where it remained all the next day anxiously awaiting the return of the scouting vessels. The Alarm is Sounded Around midnight Kara Kosh reached the anchorage with the news that the Christian fleet was then at Cephalonia, an Ionian island almost directly opposite and parallel to the mouth of the Gulf of Lepanto. With the first light of dawn the following morning, October 7th, 1571, lookouts stationed high on a peak guarding the northern shore of the gulf's entrance signaled to Kara Kosh that the enemy was heading south along the coast and would soon round the headland into the gulf itself. Prepare for Battle! The signal was relayed to Ali Pasha, who gave the order to weigh anchor. Everyone scrambled to battle stations and, as the fleet advanced, strained for the first sight of the enemy force. The Christian fleet had started to move southward toward the Gulf of Lepanto. Now only fifteen miles of open water separated the forces of Islam and those of Christendom. The Turkish fleet, which numbered over two hundred and thirty galleys and one hundred auxiliary vessels, Ali Pasha commanded the center squadron, which faced the one commanded by Don Juan of Austria. |

Spiritual Battle Preparations

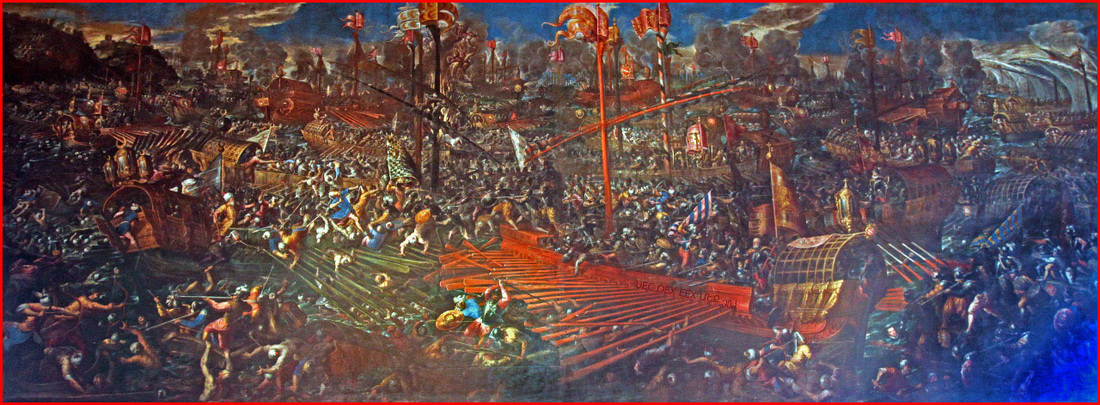

At sunrise on Sunday morning, October 7th, the chaplains on each ship were celebrating the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass as the vanguard of the fleet cruised south along the coast, turned the corner at the headlands, and entered the Gulf of Corinth. Since dawn the Turks had been moving in their direction from the east, with the advantage of having the wind at their back. While the ships of the League maneuvered from file to line abreast, Don John, with crucifix in hand, passed by each galley shouting encouragement and was met, as he made his way through the line, with tremendous applause and enthusiasm. By using tact and understanding, and forcefulness when necessary, he had welded many disparate elements into a united fleet. Although the Christian galleys were outnumbered, around 290 to 212 (these numbers vary greatly from one historian to another), they had superior firepower in cannon and arquebuses (primitive rifles), while the Turks relied mostly on bows and arrows. By nine o’clock the two lines were fifteen miles apart and closing fast. Wind Blows in Christian's Favor Just before contact was made, the wind that had been favoring the Turks shifted around from the east to the opposite direction. This was important for the six large galleasses, which were much larger, heavier and more sail reliant for their speed. Against the wind, they could barely move, other than by oars; but rowing such a large ship was slow-going, but with the wind in their sails, in addition to oars for more precise maneuverability, and being loaded with many cannons, they would suddenly became a lethal fighting force. |

BATTLE FORMATIONS AND THE BATTLE BEGINS

|

The Christian Fleet

As the Turks were planning further invasion of Europe, a coalition of Christian forces under John of Austria included 206 galleys and 6 galleasses. The Christian fleet consisted of 109 galleys and 6 galleasses from the Republic of Venice, 80 galleys from Spain, 12 Tuscan galleys of the order of St. Stephen, 3 galleys each from the Republic of Genoa, the Knights of Malta and the Duke of Savoy, as well as some privately owned galleys. The fleet was manned by almost 13,000 sailors, 43,000 rowers and 28,000 soldiers, including 10,000 Spanish, 7,000 German, 6,000 Italian and 5,000 Venetian soldiers. Most of the 43,000 rowers were free oarsmen. The Turkish Fleet The Christian League was outnumbered by the larger Turkish fleet of 230 galleys and 60 galliots. Under the command of Ali Pasha, the 13,000 experienced sailors were drawn from all the maritime nations of the Ottoman Empire: Egyptians, Syrians, Greeks and Berbers. The Turkish fleet included 34,000 soldiers. |

Comparing the Opposing Forces

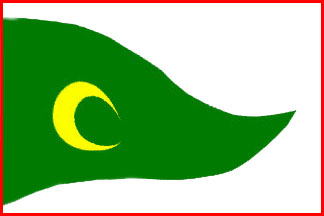

While the Christians were outnumbered in every other way, the Christian League had two significant advantages. Their infantry were definitely superior, and the Christians had 1,815 canons, compared to 750 among the Turkish vessels. The Christians also had more advanced muskets, while the Ottomans trusted in their greatly feared composite bowmen. Unlike the Christian fleet, the Turkish fleet was powered entirely by Christian slaves and prisoners of war forced to row in chains. According to naval practice in those days, the moment two rival fleets finally assumed their respective battle formations, the leader of one would fire a piece of artillery as a challenge to fight, and the opponent would answer by firing two cannon to signify that he was ready to give battle. This day it was the Turks who made the challenge, and the sharp report from Ali Pasha's flagship was quickly followed by double round from Don Juan's artillery. At this time a large green silk banner, decorated with the Muslim crescent and holy inscriptions in Arabic, was hoisted on the Turkish flagship. |

THE START OF FIVE BLOODY HOURS

|

The Cross and the Crescent

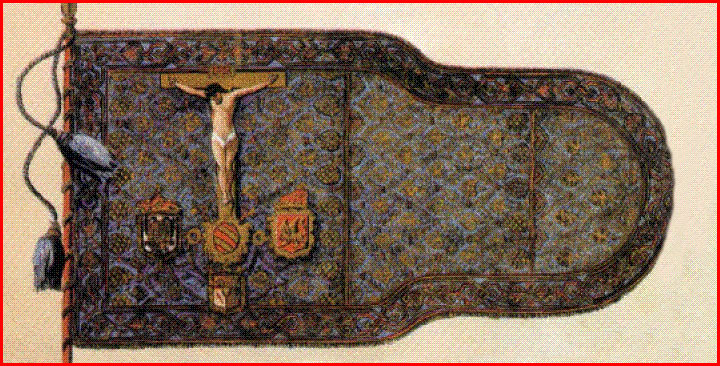

Now the setting was complete. It was eleven in the morning when the battle commenced and it would last five bloody hours. Ali Pasha's war galleys were deployed in a gigantic crescent. At this time a large green silk banner, decorated with the Muslim crescent and holy inscriptions in Arabic, was hoisted on the Turkish flagship. In the center, the Christians could see Ali Pasha's green and gold battle pennant streaming high on the mast of his flagship, the Sultana. The Islamic pennant was covered with verses from the Qur'an and emblazoned with the name "Allah" embroidered 28,900 times in gold calligraphy. It was the banner of the Sultan and one of the Islamic treasures of Mecca. The Prophet himself had carried the sacred symbol—it had never been captured in battle. The Banner of Christ Crucified Don John signaled that he intended to engage. He ordered that the battle pennant of the Holy League be run up the mast of his command ship, the Real. The great banner, blessed and given to the Holy League by Pius V, unfurled to display a gigantic cross on which was depicted the Crucified Christ. The consecrated banner was heralded by a great shout from the soldiers of the Holy League who until this time had been ominously quiet. By contrast, the Muslim fleet was advancing in a cacophony of sound—ululating war cries and prayers, random shots, clashing gongs and banging cymbals, and blaring bugles, all meant to attack the enemy's courage and shatter his nerve. The cross and the crescent fluttered aloft, symbolizing the two religions and the two hostile Civilizations of Christendom and Islam, whose forces were about to meet in the decisive battle of their long and bitter holy war. Priests with Crucifixes The war galleys of the Holy League continued to struggle with a head wind, while the galley slaves of the Ottoman fleet rested at their oars. Priests on the Christian galleys moved about the decks with raised crucifixes, blessing the men and hearing final confessions. Every man on board, whether slave or free, held a Rosary and implored the Blessed Virgin for victory in the coming battle. Their prayers joined those of countless Christians throughout Europe who were also praying the Rosary, as requested by the Pope. Don John climbed into a small galliot and rowed across the line of his advancing armada, calling out to his men, "You have come to fight the battle of the Cross—to conquer or to die. But whether you die or conquer, do your duty this day, and you will secure a glorious immortality." Then, he went back to his flagship, the Real, and knelt at the bow, eyes raised to Heaven, humbly praying that the Almighty bless His people with victory. Across the fleet, officers and men followed his example by dropping to their knees. With eyes fixed on the consecrated banner streaming from the mast of the Real, they petitioned the Lord of Hosts for help in the coming struggle. |

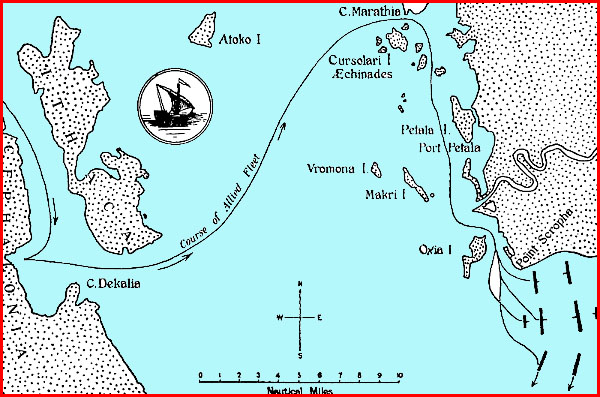

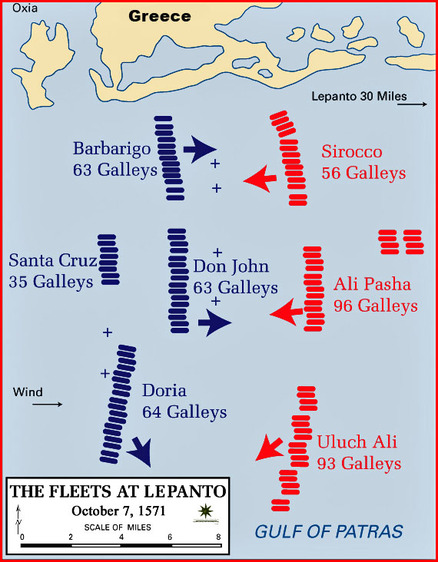

The Breathe of God Blows

Then, a miracle occurred. The wind opposing the Christian fleet switched allegiance; it came completely around and began to blow against the Muslim fleet. Across the galleys of the Holy League, lateen sails were quickly raised just as Ottoman sails were hastily dropped. The sails of the Christian fleet filled as if from a "mighty and confident breath". The Ottoman galley slaves were roused from under their benches and whipped into action. Throughout the Christian fleet, slaves and convicts who had been chained to their benches were unshackled and handed swords or half pikes. None doubted that a Mighty Providence had intervened on their behalf. They had all been promised freedom in the event of a victory. Favorable winds freed up thousands of Christians for the coming battle. In contrast, each galley slave in the Muslim fleet remained chained to his bench. If his galley went down, he perished with it. The Christian Fleet The Christian fleet maintained an extended front of about three miles as it closed on its adversary. On the far right was a squadron of sixty-four galleys commanded by Gian Andrea Doria of Genoa. The center, or main battle commanded by Don John had sixty-three galleys. The ships of his vice admirals were on either side of the Real—on the right, the commander of the papal fleet, Antonio Colonna, and, on the left, Sebastian Veniero, the fiery captain-general of the Venetians, who at seventy-six was the oldest man fighting at Lepanto. The left wing of the Christian line had another sixty-three galleys and was commanded by the Venetian Agostino Barbarigo. A reserve squadron of thirty-five galleys under the exceptionally brave and competent Marquis of Santa Cruz was centered to the rear of the main battle. The reserve under Santa Cruz would play a critical role in the outcome of the looming engagement. The Turkish Fleet Ali Pasha was in direct command of the ninety-six warships comprising the Ottoman main battle opposite Don John. He had deployed on his right his best commander, Muhammad Sirocco, with fifty-six galleys of low draft—their mission was to turn the flank of the Venetian left wing by sailing as close to the shoreline as possible, a place where Venetian galleys with their deeper draft couldn't sail. On his left, Ali Pasha placed the Algerian Uluch Ali and ninety-three galleys; their mission was to extend the Christian right and try to detach it from the main battle. It was a good plan and might have succeeded were it not for the surprises the Christians had in store for Ali Pasha and his men. |

|

|

|

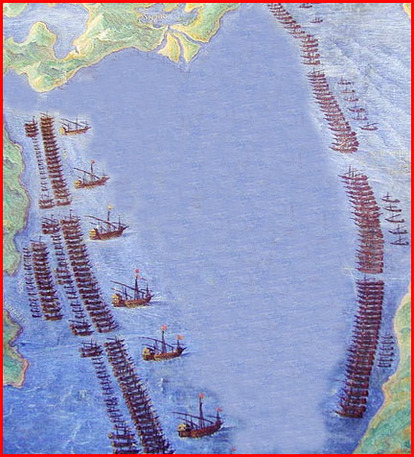

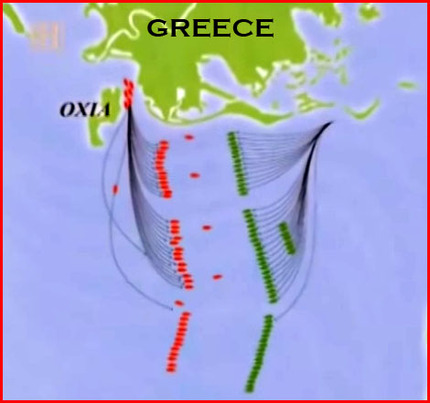

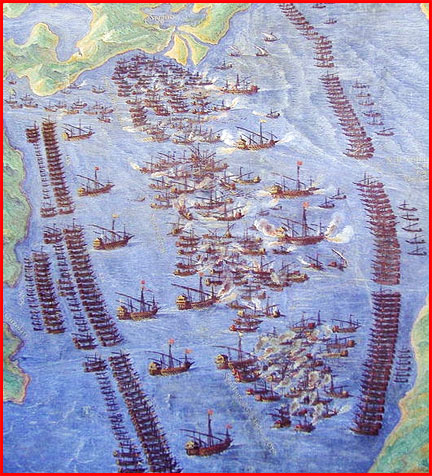

The pictures below show various simulations of the opening exchanges between the two fleets, before finally locking together in bloody hand-to-hand combat.

|

|

|

|

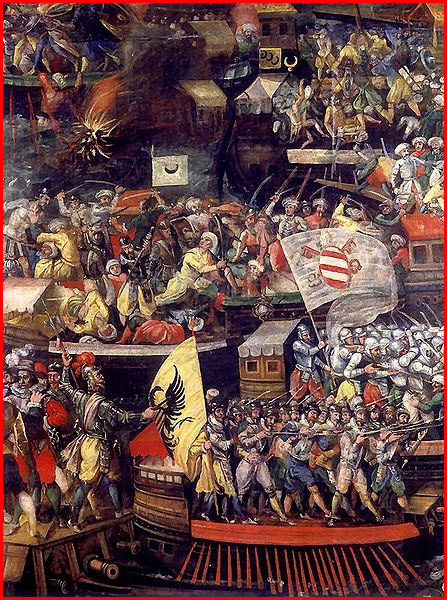

When the battle started the Turks mistook the large galleasses to be merchant supply vessels and set out to pirate them. The first surprise was the six heavily armed war galleys (galleasses) placed a mile in advance of the Christian line. When All Pasha's galleys passed these ungainly but deadly vessels, they came under fire from four hundred arquebusiers (musket or riflemen), who fired massed volleys into the Janissaries (the elite Turkish troops) packed on the decks of the Muslim galleys.

The next surprise was uncovered as the Turkish ships drew alongside what they thought were merchant ships, because the galleasses were a new Venetian innovation, carrying a tremendous battery of artillery. The fifty-four cannon that were mounted beneath the high decks of each galleass, fired broadsides into the Turkish galleys as they attempted to pass the great ships. This proved to be disastrous for the Turks, as a single volley destroyed some Ottoman war galleys. With the very first barrage many Turkish galleys were sunk and over a twenty were badly damaged. The 6 Venetian galleasses sank up to 70 Turkish galleys before the rest of the fleet could engage. The galleasses succeeded in breaking up the Ottoman formations. A large segment of the advancing crescent was disrupted before it even met the extended battle line of the Christian fleet. It was the very first time that the high-walled galleasses with their banks of cannon were ever used in battle. Lepanto signaled the end of oared galleys. Future battles would be decided by broadside cannon and sail and not by infantry assaulting from the decks of oared galleys. The third surprise in store for Ali Pasha and his fleet was the strange appearance of the regular Christian war galleys. Don John, on the advice of the Genoese admiral Andrea Doria, had ordered the removal of the iron rams that were mounted on the bows of their galleys. Andrea Doria was a seasoned veteran of galley warfare. He had observed that the ram would not allow the main cannon in the bow to depress at close range—most shots were sent high and harmlessly into the enemies sails and rigging. Without their iron rams, the Christians were able to deliver devastating cannon fire from the from the front of their galley, aimed at the water line of the attacking galleys, often sinking them with a single volley. |

On the left side of the Christian line, the galleys of the Venetian admiral Agustin Barbarigo remained locked in a desperate struggle. Barbarigo had barely managed to avoid having his line turned by the very skillful Ottoman commander, Muhammad Sirocco, who almost outflanked the galleys of Agostino Barbarigo of Venice, commander of the left wing, maneuvering between the shore and the Venetians. He made a quick dash between the Venetian commander’s left wing and the shore line, hoping to swing around and trap Don John’s center squadron from behind.

Barbarigo quickly slid over and intercepted the Turks, but several galleys had slipped by and attacked him from the rear. When his squadron closed in to help, Barbarigo, standing in the midst of fierce struggle, lifted the visor of his helmet to coordinate their attack. An arrow pierced his eye and he had to be carried below. However, his quick, self-sacrificing action had prevented Sirocco’s flanking movement. The battle was fearsome. Capuchin priests were seen at the front of many boarding parties, leading the assault with an uplifted crucifix. On some Turkish galleys, Christian slaves managed to break their chains and join the battle against their Turkish masters. Admiral Barbarigo was found to have been mortally wounded in the struggle, taking the arrow to the eye. Lingering below decks in agony, his officers brought him news that Muhammad Sirocco had fallen and the enemy was defeated. Giving up his last breath, he exclaimed, "I die contented." The Christian left wing then trapped the Muslim right wing of fifty-six galleys against the shore and with the help of vessels from the rearguard sent in by another Holy League commander, Don Álvaro de Bazán, the Marquis of Santa Cruz, methodically destroyed the entire Ottoman right wing in two hours. |

AFTER THE CANNON BARRAGE, THE REMAINING SHIPS LOCK TOGETHER AND BOARD ONE ANOTHER FOR HAND-TO-HAND COMBAT

|

The Two Leaders Collide

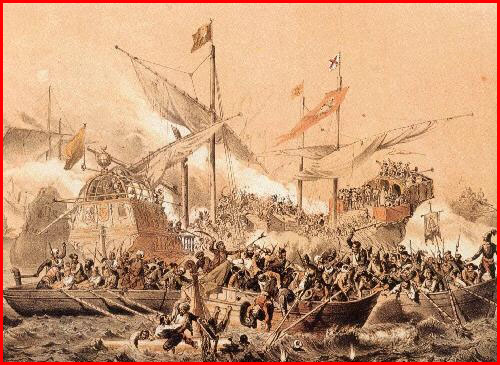

Meanwhile, a fierce mêlée developed between the Christian and Ottoman center. The center of both the Christian and Ottoman battle lines bore down heavily on each other without any thought of subterfuge or trickery. As the fleets closed for battle, Don John ordered his helmsmen to steer for the enemy's flagship. So, too, did Ali Pasha. Usually, the flagships stand off from the heat of battle, but not this time; both supreme commanders set a hard course for each other. Both leaders ignored the convention of galley warfare that flagships did not engage one another. Christian Flagship Boarded The Muslims were yelling, screaming, and banging anything that would make noise. The Christians were in an ominous silence, weapons in one hand, Rosaries in the other. The two flagships collided in a staggering crash, the prow of Ali Pasha's larger, heavier Sultana gained the initial advantage by ramming into the Real up to the fourth bench of rowers on Don John's Real. Don John threw across grappling irons and pulled the two ships together and boarded. Instantly, a dozen Turkish ships closed in behind Ali Pasha, supplying him with thousands of Janissaries (the elite Turkish fighting forces). Grappling lines quickly locked the two ships into a deadly duel. Surprise Welcome On Board The next surprise occurred when Ali Pasha and his Janissaries attempted to board the Christian galleys. When the fanatically brave Janissaries began to climb the sides of the Real, they reached an unfamiliar, deadly obstacle: all of Don John's galleys had boarding nets stretched from stem to stern. Unable to board, the Janissaries hung in the nets, absorbing the withering gunfire fire of the Spanish infantry massed on board the Real. Their bravery approached insanity as they tried to grapple their way up the sides of the Real, only to be shredded by musketry. Blood Soaked Decks, Blood Stained Sea More than eight hundred men were now packed shoulder to shoulder on the decks of the two ships, raining arrows and musket balls point-blank into one another. The carnage was terrible. Scores of dead and dying men soon littered both decks, while more reinforcements piled on board for more bloodshed. Ali Pasha had planned to counter the superior Christian firepower by using his reinforcements from the reserve, until Muhammad Sirocco and Uluch Ali outflanked the Christian wings and could attack the Christian center squadron from behind—which is always the most vulnerable spot. Despite heavy losses from the large cannons of the Christian galleasses, some Ottoman galleys penetrated the Christian ranks and more of Ali Pasha's reinforcements boarded the Real. Veniero and Colonna hugged the Real from either side and poured their troops onto the Real to help repel the Turkish boarders. Reinforcements arrived from other galleys. Some two dozen ships became interlocked, thus forming a floating battlefield. The battle raged back and forth over the blood-soaked, carnage-strewn decks. The Tide Turns Soon, however, the Ottoman center was overwhelmed. Don John's Spanish infantry was forced to muster three times, before they gained a foothold on the blood-smeared decks of the Sultana. The arquebus (muskets) of the West slowly overcame the traditional composite, recurve bows and arrows of the East. Even though the Turkish bowmen might get off as many as thirty arrows before the arquebusier could reload his arquebus for another shot, the Turkish arrows could not penetrate the armor of the Spanish infantry. The musket balls of the arquebusiers devastated the unarmored Turks, blowing wide swaths through their massed ranks. |

Don John Wounded, Ali Pasha Killed

Don John was wounded in the final assault on the Sultana. Ali Pasha went down with a musket ball to the forehead. An armed convict, one of those freed and armed by Don John, quickly severed Ali Pasha's head, against the wishes of Don John, and hoisted it on a pike. He carried the grisly symbol of victory to the quarterdeck of the Real. However, when his severed head was displayed on a pike from the Spanish flagship, it contributed greatly to the destruction of Turkish morale. With their commander visibly dead, the men of the Sultana were finally overrun and subdued. Simultaneously, the sacred banner of the Prophet was swept from the masthead and the papal banner raised in its place. A blare of trumpets and cries of "Victory" all down the Christian line signaled Don John's capture of the Muslim flagship. Even after the battle had clearly turned against the Turks, groups of Janissaries (the Turkish elite soldiers) still kept fighting with all they had. It is said that at some point the Janissaries ran out of weapons and started throwing oranges and lemons at their Christian adversaries, leading to awkward scenes of laughter among the general misery of battle. Morale Collapses When Ali Pasha was killed and his flagship, the Sultana, was taken in tow by the Real, the Ottoman center collapsed. All the Ottoman ships in the center were sunk or taken and their crews massacred, almost to the last man. The sea was red with blood. Last Chance Fails The clash between the seaward squadrons started later. One last hope for the Ottomans remained. Uluch Ali and Gian Andrea Doria, the most skilled sea captains on either side, tried to outmaneuver each other. Uluch Ali, the clever Barbary corsair, out-foxed Doria by dragging him too far to the Christian right. While the bulk of his galleys engaged Doria's right and center, Uluch Ali managed to inflict serious damage upon some 15 of Doria's galleys that had broken formation at the left flank. He then cut back and slipped through the opened hole. Cardona, with a handful of galleys, attempted to block Uluch Ali, but was wiped out. Uluch Ali proceeded to attack the Christian center's right flank in order to help the overwhelmed Ottoman center, but it was too late; Ali Pasha was already dead, and Santa Cruz sent his remaining Christian reserve against Uluch Ali. Santa Cruz, who was giving valuable support to the center squadron, broke away to intercept Uluch Ali. Seeing his opportunity for an unhindered attack on the Christian rear disappear and that he could not save the day, Uluch Ali escaped into the open sea with some 30 galleys, while having to cut the ropes of the captured Christian ships that he was towing. Most of his squadron was destroyed when Doria wheeled about and assisted Santa Cruz in finishing the weakened Ottoman fleet. The Christian victory was complete. The Holy League fleet destroyed almost the entire Ottoman navy with its crew and ordnance. Over 210 Turkish ships were lost. Of these, 117 galleys and 10 galliots were captured in good enough condition to be used by the Christian forces in future. The only prize captured by the Turks was one Venetian galley. On the Christian side, 20 galleys were destroyed and 30 damaged so seriously that they had to be scuttled. The Turkish losses were estimated at 30,000 dead and wounded and 15,000 prisoners. On the Christian side, 7,500 soldiers, sailors and rowers were dead, but twice as many Christian prisoners, around 15,000, were freed from Turkish galleys. |

|

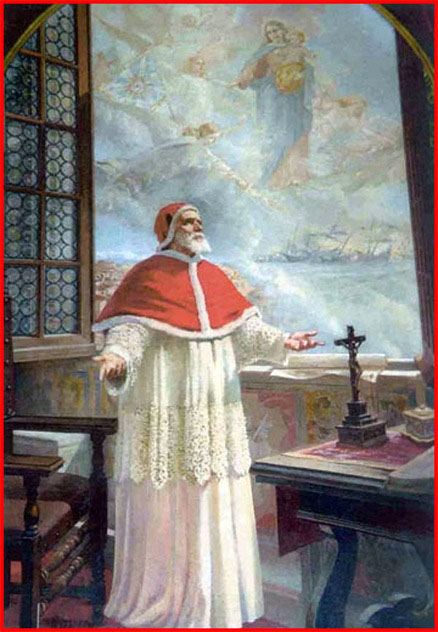

Papal Victory Vision

At the time the battle was won, Saint Pius V was studying financial sheets with the papal treasurer. He rose, went to the window and looked toward the east. When he turned around his face was radiant with supernatural joy, and he exclaimed,“The Christian fleet is victorious!” After human agencies verified the news two weeks later, Saint Pius V added the Feast of the Holy Rosary to the Church calendar and the invocation Auxilium Christianorum to the litany of Our Lady, since the victory was due to her intercession. The Holy League credited the victory to the Virgin Mary, whose intercession with God they had implored for victory through the use of the Rosary. Our Lady of Guadalupe at Lepanto Interestingly enough, another surprising version of Our Lady played a role at Lepanto. Andrea Doria had kept a copy of the miraculous image of Our Lady of Guadalupe given to him by King Philip II of Spain in his ship's state room. The second archbishop of Mexico, Don Fray Alonso de Montufar, had a small reproduction of the Sacred Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe made and, after touching it to the original, sent it to King Philip of Spain in 1570. The archbishop knew of the impending battle and asked that the image accompany the Holy League, as he believed that it would work a miracle as the original image had so many times in Mexico. The image was mounted in the cabin of Admiral Giovanni Andrea Doria. It was Andrea Doria's fleet that was under the heaviest attack from the Turks when the wind suddenly shifted, changing the momentum of the battle and leading to the decisive victory by the Holy League. First Major Ottoman Naval Defeat since 15th Century The engagement was a significant defeat for the Ottomans, who had not lost a major naval battle since the fifteenth century. The defeat was mourned by them as an act of Divine Will, contemporary chronicles recording that "the Imperial Fleet encountered the fleet of the wretched infidels and the will of God turned another way." To half of Christendom, this event encouraged hope for the downfall of "the Turk" of the Ottoman Empire, who was regarded as the "Sempiternal Enemy of the Christian". Indeed, the Empire lost all but 30 of its ships and as many as 30,000 men, and some Western historians have held it to be the most decisive naval battle anywhere on the globe since the Battle of Actium of 31 BC. The Turks claim that the heavy cannons of the Venetian galleasses made the difference. I think the two cannons that did the most damage were the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass that was offered on board the ships and the Rosaries that were prayed by all the Christian soldiers and sailors for three hours non-stop before the battle. Our Lord clearly said that "Without Me, you can do nothing!" and we know that "grace perfects nature". Here, at Lepanto, Christ and His grace was desperately needed and the Mediatrix of All Grace made sure of that all went according to plan. Massive Rebuilding of Ottoman Navy Despite the decisive defeat, the Ottoman Empire rebuilt its navy with a massive effort, by largely imitating the successful Venetian cannon-laden galeasses, in a very short time. By 1572, about six months after the defeat, more than 150 galleys and 8 galleasses, in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean. With this new fleet the Ottoman Empire was able to reassert its supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean. |

Weak Treaties with Ottoman Empire

On March 7th, 1573 the Venetians thus recognized by treaty the Ottoman possession of Cyprus, whose last Venetian possession, Famagosta, had fallen to the Turks under Piyale Pasha on August 3rd, 1571, just two months before Lepanto, and remained Turkish for the next three centuries, and that summer the Ottoman Navy attacked the geographically vulnerable coasts of Sicily and southern Italy. Proud Empty Boast Sultan Selim II's Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu, argued to the Venetian emissary Marcantonio Barbaro that the Christian triumph at Lepanto made no lasting harm to the Ottoman Empire, while the capture of Cyprus by the Ottomans in the same year was a significant blow, pompously saying that: “You come to see how we bear our misfortune. But I would have you know the difference between your loss and ours. In wresting Cyprus from you, we deprived you of an arm; in defeating our fleet, you have only shaved our beard. An arm when cut off cannot grow again; but a shorn beard will grow all the better for the razor.” Avoiding a Fight Numerous historians pointed out the historical importance of the battle and how it served as a turning point in history. For instance, it is argued that while the ships were relatively easily replaced, it proved much harder to man them, since so many experienced sailors, oarsmen and soldiers had been lost. The loss of so many of its experienced sailors, soldiers and archers at Lepanto sapped the fighting effectiveness of the Ottoman Navy—for though you can build a ship in months, it takes years of training and battle experience to form efficient and effective battle oarsmen, sailors, soldiers and archers—a fact emphasized by the Ottoman Empire’s avoidance of major confrontations with Christian navies in the years following the battle. The True Victors The true Victors at Lepanto were Our Lord and Our Lady: through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the Holy Rosary. Though galleys, crossbows, primitive rifles and such are out of date, the pillars of this victory are not out of date. Don Bosco's vision of the Two Pillars in the Sea points to these weapons having to be used once again in the future! (click here). Pope St. Pius V in 1572 ordered an annual commemoration of our Lady of Victory to be made to implore God's mercy on His Church and all the faithful, and to thank Him for His protection and numberless benefits, particularly for His having delivered Christendom from the arms of the infidel Turks by the sea victory at Lepanto in the previous year, a victory which seemed a direct answer to the prayers and processions of the Rosary confraternities at Rome made while the battle was actually being fought. A year later Pope Gregory XIII changed the name of the observance to that of the Rosary, fixing it for the first Sunday in October (the day of Lepanto). Pope Clement XI decreed that the feast of the Holy Rosary should be observed throughout the western Church. The feast is now kept on the date of the battle of Lepanto, October 7th. |

Web Hosting by Just Host