| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CHOOSE THE MIRACLE YOU WISH TO READ ABOUT FROM THE LINKS BELOW

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

THE VICTORY OF THE HOLY ROSARY AT LEPANTO

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

PART FIVE

SHIPS—SAILORS—SOLDIERS—WEAPONS—TACTICS

SHIPS—SAILORS—SOLDIERS—WEAPONS—TACTICS

|

The Advance of the Juggernaut

Since the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 the inexorable might of the Ottoman Empire has spread throughout the Middle East and into the Balkans. By 1529, they were strong enough to attack the city of Vienna and their failure to capture that city was the first major setback in nearly a century. Since then the war between Christianity and Islam had taken to the seas. Christian Fleets were annihilated at the battles of Prevesa (1538) and Djerba (1560) and Ottoman dominance of the Eastern Mediterranean was assured. Their attempt to gain access to the Western Mediterranean was only held back only by the heroic defense of the Knights of St John on Malta in 1565, six years before Lepanto. Nevertheless that defeat at Malta, where they had greatly outnumbered the Christians, blunted the sword of Islam and from that time, the Ottomans attempted to re-establish their dominance. They year before Lepanto, they attacked Venetian Cyprus. The Republic of Venice, which was in decline and too worldly, lacked the strength to stand alone against the Ottomans. They were even divided as to whether or not to fight over Cyprus—some preferring to negotiate a peace with the Ottomans so that they could carry on trading on the seas. |

Christian Coalition Finally Forms

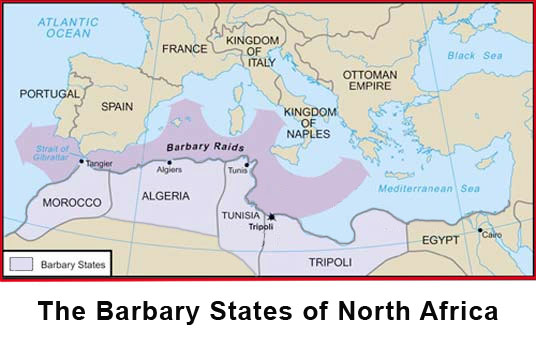

Pope St. Pius V saw the danger to the Faith and, seeing that no individual country of state could stand against the advance of this juggernaut, announced the creation of a Holy League to stand against Turkish aggression. During the 16th century, the great Christian naval powers of the Mediterranean were Spain, the Papal states, Venice and Genoa, as well as the Knights of Malta. These states were organized by the pope into a 'Holy League' for a united defence against the Ottomans. Against their better judgment, Venice's rivals answered the call―for Cyprus was a territory of Venice their rival in trade. The combined fleet gathered at Crete in September of 1570, but their first intended campaign failed before it started, because Cyprus fell before they could arrive to relieve it. Turkish success at Cyprus now allowed their fleet to strike deeper into Christian Territory. By August of 1571 the Ottomans had established a base at Lepanto on the western coast of Greece. The Holy League Fleet had by now congregated at the arranged meeting point of Medina, on the island of Sicily, from where it would sail together eastwards, to halt the Turkish fleet. But it was not just the Musilm Ottoman Empire in the east that was a thorn in Europe’s side—the Muslim Barbary pirates of North Africa were also wreaking havoc throughout the western Mediterranean. |

SUMMARY OF THE MAIN BATTLES LEADING UP TO THE BATTLE OF LEPANTO

1535 Siege of Tunis Christian victory

In 1535 Charles V led a Christian army of 60,000 men against Tunis, which had recently been taken by the Ottomans. After a siege at La Goletta, Tunis was taken and 30,000 inhabitants slaughtered.

1509 Battle of Oran Spanish victory

Fought May 17th, 1509, between the Moors and the Spaniards, under Navarro. The Spaniards, late in the evening, attacked and drove off the Moors from a strong position on the heights above the city. They then stormed the city itself, climbing the walls by placing their pikes in the crevices of the stones. The Moors lost in the battle and the storm 4,000 killed and about 8,000 prisoners, while the losses of the victors were very small.

1538 Battle of Preveza Ottoman victory

This naval battle was fought September 28th, 1538, in the Ionian Sea between an Ottoman fleet of 122 galleys under Barbarossa, and 162 Christian galleys under Andrea Doria. The winds were against the Christians and the Turks were able to destroy 13 ships and capture 36 while suffering minimal losses. The next morning Doria retreated with his Genoese fleet, leaving the Venetians to their fate.

1541 Siege of Algiers Algiers victory

A large fleet was fitted by Charles V for a campaign against the pirate city of Algiers, but a tremendous storm destroyed much of the fleet en route, and insufficient supplies remained to conduct a siege. The retreating forces were harassed in their departure, and many more ships were sunk on the return. Over 150 ships and 30,000 Spaniards were lost or captured.

1560 Battle of Djerbeh Ottoman victory

Fought 1560, between the fleet of Suleiman I, Sultan of Turkey, under Piycala Pasha, and the combined squadrons of Malta, Venice, Genoa and Florence. The Christian fleet was utterly routed, the Turks securing thereby the preponderance in the Mediterranean.

1570 Siege of Famagusta Ottoman victory

This siege was part of the conquest of the entire island of Cyprus. Famagusta was the last fortress on the island to hold out was besieged by the Turks under Mustapha Pasha, in October, 1570, and was defended by 7,000 men, half Venetians, half Cypriots, under the governor Marcantonio Bragadino. The garrison held out until August 6th, 1571, when it capitulated, marching out with the honors of war. After the surrender, however, Mustapha tortured and murdered in cold blood, Bragadino and four of his lieutenants. The Turks lost 50,000 men in the course of the siege.

In 1535 Charles V led a Christian army of 60,000 men against Tunis, which had recently been taken by the Ottomans. After a siege at La Goletta, Tunis was taken and 30,000 inhabitants slaughtered.

1509 Battle of Oran Spanish victory

Fought May 17th, 1509, between the Moors and the Spaniards, under Navarro. The Spaniards, late in the evening, attacked and drove off the Moors from a strong position on the heights above the city. They then stormed the city itself, climbing the walls by placing their pikes in the crevices of the stones. The Moors lost in the battle and the storm 4,000 killed and about 8,000 prisoners, while the losses of the victors were very small.

1538 Battle of Preveza Ottoman victory

This naval battle was fought September 28th, 1538, in the Ionian Sea between an Ottoman fleet of 122 galleys under Barbarossa, and 162 Christian galleys under Andrea Doria. The winds were against the Christians and the Turks were able to destroy 13 ships and capture 36 while suffering minimal losses. The next morning Doria retreated with his Genoese fleet, leaving the Venetians to their fate.

1541 Siege of Algiers Algiers victory

A large fleet was fitted by Charles V for a campaign against the pirate city of Algiers, but a tremendous storm destroyed much of the fleet en route, and insufficient supplies remained to conduct a siege. The retreating forces were harassed in their departure, and many more ships were sunk on the return. Over 150 ships and 30,000 Spaniards were lost or captured.

1560 Battle of Djerbeh Ottoman victory

Fought 1560, between the fleet of Suleiman I, Sultan of Turkey, under Piycala Pasha, and the combined squadrons of Malta, Venice, Genoa and Florence. The Christian fleet was utterly routed, the Turks securing thereby the preponderance in the Mediterranean.

1570 Siege of Famagusta Ottoman victory

This siege was part of the conquest of the entire island of Cyprus. Famagusta was the last fortress on the island to hold out was besieged by the Turks under Mustapha Pasha, in October, 1570, and was defended by 7,000 men, half Venetians, half Cypriots, under the governor Marcantonio Bragadino. The garrison held out until August 6th, 1571, when it capitulated, marching out with the honors of war. After the surrender, however, Mustapha tortured and murdered in cold blood, Bragadino and four of his lieutenants. The Turks lost 50,000 men in the course of the siege.

|

THE PROBLEM OF THE MARAUDING BARBARY PIRATES

The Barbary Pirates

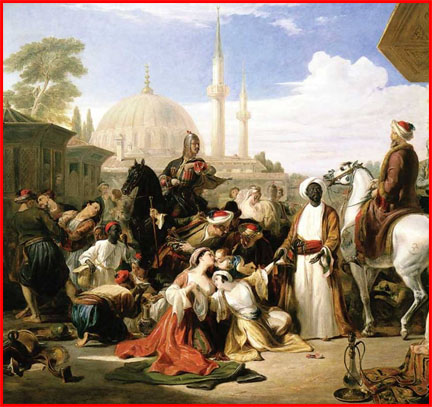

The Turkish fleet was aided by the Barbary pirates, who were sometimes called Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs. They were pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe as the Barbary Coast, a term derived from the name of its Berber inhabitants. The Barbary Coast, which extends from Morocco through modern Libya, was home to a thriving man-catching industry from about 1500 to 1800. The great slaving capitals were of course the aforementioned ports of Salé in Morocco, Tunis, Algiers, and Tripoli, and for most of this period European navies were too weak to put up more than token resistance. The Barbary pirates first arose after the Christian Spanish drove the Muslim Moors out of Granada, Spain, in 1492. They did not become an organized body, under the protection of the North African port cities, until a few years later, under the leadership of Barbarossa, a pirate chieftain who became an Admiral in the navy of Ottoman Empire. After leading several daring raids in the Mediterranean and essentially taking over the cities of Djerba and Algiers, he was appointed commander and chief of the Ottoman Navy. In this position he fought the united fleets of the Christians at Preveza, helping to establish Ottoman domination of the Mediterranean. The defeat at Preveza, combined with the utterly disastrous Spanish siege of Algiers several years later, dealt two serious blows the Christian fleets in the Mediterranean, and established a firm alliance between the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary corsairs. Dragut was another leading pirate captain who later became an Ottoman Admiral, and so for a time the Barbary pirates were protected and encouraged by the Ottoman navy. The most well-known Christian sea captains who fought pirates during this period were Andrea Doria of Genoa, and Don John of Austria, both of whom fought under the Spanish flag. Barbary Slave Trade Their piracy extended throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa's Atlantic seaboard and even South America, and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland, but they primarily operated in the western Mediterranean. In addition to seizing ships, they engaged in Razzias, raids on European coastal towns and villages, mainly in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, but also in the British Isles, the Netherlands and as far away as Iceland. The main purpose of their attacks was to capture Christian slaves for the Ottoman slave trade as well as the general Muslim market in North Africa and the Middle East. While such raids had occurred soon after the death of Muhammad (632) with the Muslim conquest of the North African region throughout the 670’s, and pirate activity by Muslim populations had been known in the Mediterranean since at least the 9th century, the terms “Barbary pirates” and “Barbary corsairs”, are normally applied to the raiders active from the 1500’s onwards. It was at this time that the frequency and range of the slavers' attacks increased and Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli came under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, either as directly administered provinces, or as autonomous dependencies known as the Barbary States. Similar raids were undertaken from Salé and other ports in Morocco. During the first period (1518–1587), the beylerbeys (meaning “commanders of commanders”) were admirals of the sultan, commanding great fleets and conducting war operations for political ends. They were slave-hunters and their methods were ferocious. Muslim Fury for Christian Slaves The trans-Atlantic trade in negroes was strictly commercial, but for Arabs, memories of the Crusades and fury over expulsion from Spain in 1492, seem to have fueled an almost jihad-like Christian-stealing campaign. “It may have been this spur of vengeance, as opposed to the bland workings of the marketplace, that made the Islamic slavers so much more aggressive and initially (one might say) successful in their work than their Christian counterparts,” writes Prof. Davis. During the 16th and 17th centuries more slaves were taken south across the Mediterranean than west across the Atlantic. What is most striking about Barbary slaving raids is their scale and reach. Pirates took most of their slaves from ships, but they also organized huge, amphibious assaults that practically depopulated parts of the Italian coast. Italy was the most popular target, partly because Sicily is only 125 miles from Tunis, but also because it did not have strong central rulers who could resist invasion. Massive Numbers Enslaved Large raiding parties might be essentially unopposed. The appearance of a large fleet could send the entire population inland, emptying coastal areas. In 1566, a party of 6,000 Turks and Corsairs sailed up the Adriatic and landed at Fracaville. The authorities could do nothing, and urged complete evacuation, leaving the Turks in control of over 500 square miles of abandoned villages all the way to Serracapriola. In 1544, Barbary pirates captured the island of Ischia, taking 4,000 prisoners, and enslaved some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari, almost the entire population. In 1551, the Barbary pirates enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island Gozo, between 5,000 and 6,000, sending them to Ottoman Tripolitania. In 1554, the pirates raided Vieste in southern Italy and took an estimated 7,000 slaves. In 1555, they raided Bastia, Corsica, taking 6,000 prisoners. In 1558, Barbary pirates captured the town of Ciutadella (Minorca), destroyed it, slaughtered the inhabitants and took 3,000 survivors to Constantinople as slaves. In 1563, they landed on the shores of the province of Granada, Spain, and captured coastal settlements in the area, such as Almuñécar, along with 4,000 prisoners. Algerians took 7,000 slaves in the Bay of Naples in 1544, in a raid that drove the price of slaves so low it was said you could “swap a Christian for an onion.” Spain, too, suffered large-scale attacks. After a raid on Granada in 1566 netted 4,000 men, women, and children, it was said to be “raining Christians in Algiers.” Barbary pirates often attacked the Balearic Islands, and in response many coastal watchtowers and fortified churches were erected. The threat was so severe that the island of Formentera became uninhabited. For every large-scale raid of this kind there would have been dozens of smaller ones. When they came ashore, Muslim corsairs made a point of desecrating churches. They often stole church bells, not just because the metal was valuable but also to silence the distinctive voice of Christianity. In the more frequent smaller raiding parties, just a few ships would operate by stealth, falling upon coastal settlements in the middle of the night so as to catch people “peaceful and still naked in their beds.” This practice gave rise to the modern-day Sicilian expression, pigliato dai turchi, or “taken by the Turks,” which means to be caught by surprise while asleep or distracted. Constant predation took a terrible toll. Women were easier to catch than men, and coastal areas could quickly lose their entire child-bearing population. Fishermen were afraid to go out, or would sail only in convoys. Eventually, Italians gave up much of their coast. As Prof. Davis explains, by the end of the 17th century, “the Italian peninsula had by then been prey to the Barbary corsairs for two centuries or more, and its coastal populations had largely withdrawn into walled, hilltop villages or the larger towns like Rimini, abandoning miles of once populous shoreline.” More than 20,000 captives were said to be imprisoned in Algiers alone. Most of the slaves destined for the Muslim Middle East were for sexual exploitation as concubines, in harems, and for military service on land or at sea. Those slaves who had rich families were often able to secure release through ransom, but the poor were condemned to slavery. Their masters would, on occasion, allow them to secure freedom by professing Islam and denying their Christian Faith. Some were put to hard labor in North Africa, and the unluckiest worked themselves to death as galley slaves. Before being appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Christian Fleet, Don John of Austria had been fighting the Barbary pirates along the Barbary Coast. He was well-acquainted with their tactics and methods of warfare. |

|

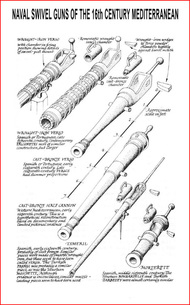

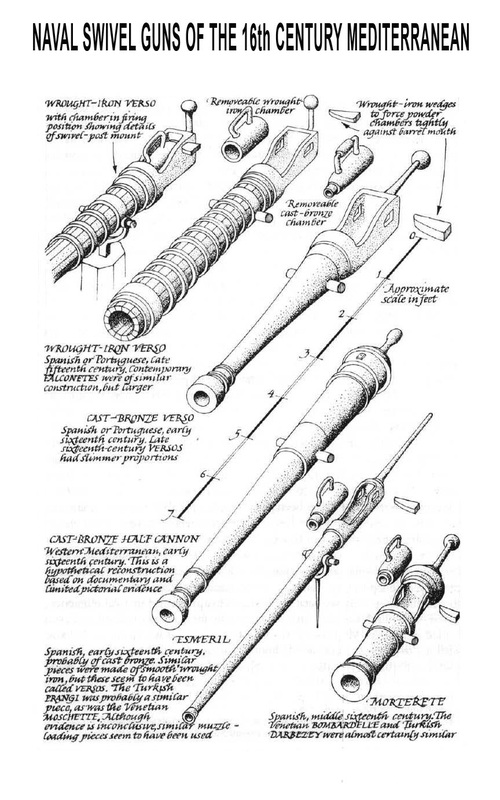

THE CHIEF WEAPONS

|

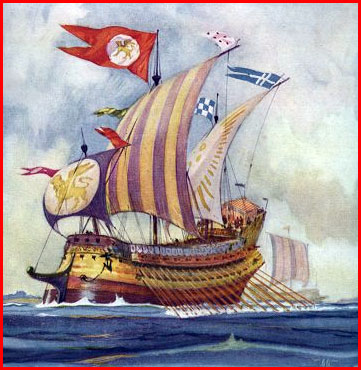

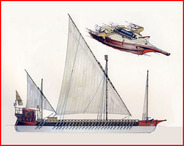

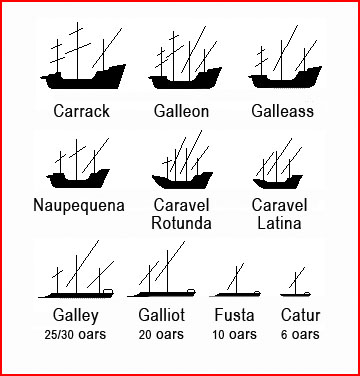

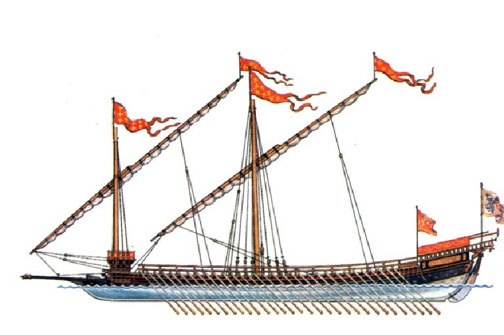

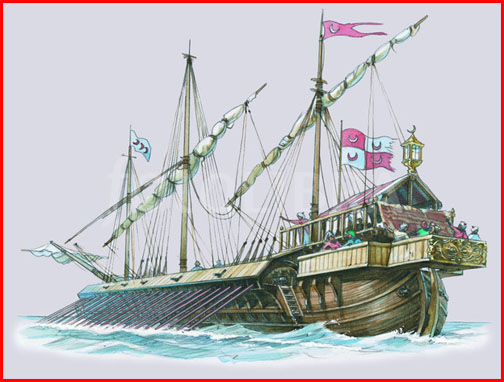

THE SHIPS OF THE BATTLE OF LEPANTO

The Galleass

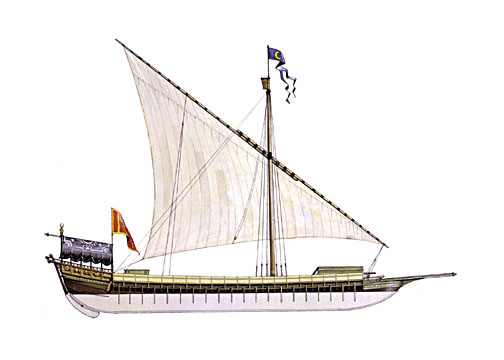

The Galleass was a broadside-cannon-armed oared warship. The galleass was an attempt to upgrade the galley with cannon and square-sail technology. It was not a spectacular success, as it was a transitional kind of ship that would evolve into the Galleon a little later on; but had its day and was a great success at Lepanto. The Christian fleet at Lepanto was the first to employ this new naval weapon: enormous galleasses, newly launched from the Arsenal at Venice, bristling with cannon and capable of delivering as much firepower as six standard galleys. They had anywhere from 30 to 40 large cannon on deck, pointing in all directions—forwards, backwards, and each side of the ship. Six of these unwieldy floating behemoths (which had to be towed into position) were to lay waste to the Turkish fleet as it crossed their path. The Galley A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by rowing. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft and low clearance between sea and railing. Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used in favorable winds, but human strength was always the primary method of propulsion. This allowed galleys freedom to move independently of winds and currents, and with great precision. The galley originated among the seafaring civilizations around the Mediterranean Sea in the early first millennium BC and remained in use in various forms until the early 19th century in warfare, trade and piracy. From the 12th century, the design of war galleys evolved into the form that would remain largely the same until the building of the last war galleys in the late 18th century. The length to breadth-ratio was a minimum of 8:1 and could be longer. It was based on the form of the galea, the smaller Byzantine galleys, and would be known mostly by the Italian term gallia sottila (literally "slender galley"), which we call, in English, a galley. A second, smaller mast was added sometime in the 13th century and the number of rowers was rose from two to three rowers per bench as a standard from the late 13th to the early 14th century. The gallee sottili, or galley, would make up the bulk the main war fleets of every major naval power in the Mediterranean, assisted by the smaller galliot, as well as the Christian and Muslim corsairs fleets using an even smaller ship called the fusta. Ottoman galleys were very similar in design, though in general smaller, faster under sail, but slower under oars. The standard size of the galley remained stable from the 14th until the early 16th century, when the introduction of naval artillery began to have effects on design and tactics. Galleys were the warships used by the early Mediterranean naval powers, including the Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans. They remained the dominant types of vessels used for war and piracy in the Mediterranean Sea until the last decades of 16th century. As warships, galleys carried various types of weapons throughout their long existence, including ram, catapults and cannons, but also relied on their large crews to overpower enemy vessels in boarding actions. They were the first ships to effectively use heavy cannons as anti-ship weapons. As highly efficient gun platforms they forced changes in the design of medieval seaside fortresses as well as refinement of sailing warships. The zenith of galley usage in warfare came in the late 16th century with battles like that at Lepanto in 1571, one of the largest naval battles ever fought. By the 17th century, however, sailing ships and hybrid ships like the xebec displaced galleys in naval warfare. The Galliot and Fusta The Galliot andr Fusta or Fuste, were a narrow, light and fast ships with shallow draft, powered by both oars and sail—in essence a small galley. The galliot was anywhere from half to two-thirds of the length of the galley, while the fusta was at the most half the length of the galley or less. The galliot typically had 12 to 20 two-man rowing benches on each side, a single mast with a lateen (triangular) sail, and usually carried two or three guns. The sail was used to cruise and save the rowers’ energy, while the oars propelled the ship in and out of harbor and during combat. The fusta had no more than 10 rowing benches on each side. The fusta was the favorite ship of the North African corsairs of Salé and the Barbary Coast. Its speed, mobility, capability to move without wind, and its ability to operate in shallow water—crucial for hiding in coastal waters before pouncing on a passing ship—made it ideal for war and piracy. It was mainly with fustas that the Barbarossa brothers, Baba Aruj and Khair ad Din, carried out the Ottoman conquest of North Africa and the rescue of Mudéjars and Moriscos from Spain after the fall of Granada, and that they and the other North African corsairs used to wreak terror upon Christian shipping and the islands and coastal areas of the Mediterranean in the 16th and 17th centuries. |

|

GUNS AND CANNONS, BOW AND CROSSBOWS, SWORDS AND DAGGERS

THE TACTICS OF NAVAL WARFARE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

|

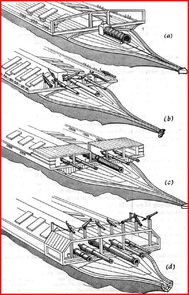

Before the advent of gunpowder and cannons on ships, naval warfare was to a large extent much like warfare on land—where two armies met and 'slugged-it-out' in close-quarter fighting. The basic tactics of warfare were as follows:

(1) You first had to sail your ship within range of the enemy ship. This would require that your ship be a fast sailing ship that could out-sail and out-maneuver the ship you targeted. Ships with sails were dependent upon the wind—and when there was no wind in their sails, they became a sitting duck that could not move. Even with the wind in their sails, they were largely dictated by the wind-direction as to what maneuvers and direction the ship could make and take. Ships with oars were independent of the wind and could take any direction they wanted, even going into reverse if needed—which would be case sometimes, after ramming the enemy. (2) Once you caught up with the enemy ship or came to a head-to-head confrontation, you would then use your archers to bombard them with arrows to kill as many as possible of the crew and troops that were on board—since the warships were largely open decked galleys, many of the enemy were vulnerable to this downpour of arrows. The aim was not to sink ships, but to deplete the ranks of the enemy crews before the boarding commenced, which decided the outcome. (3) Once the enemy strength was judged to have been reduced sufficiently, the fleets closed in, the ships grappled each other, and the marines and upper bank oarsmen boarded the enemy vessel and engaged in hand-to-hand combat. On Byzantine galleys, the brunt of the fighting was done by heavily armed and armored troops. These would attempt to stab the rowers through the oarports to reduce mobility, and then join the melée. If boarding was not deemed advantegous, the enemy ship could be pushed away with poles. (4) Naval warfare in the Mediterranean rarely used sails, and the use of rams specifically required oarsmen over sails in order to maneuver with accuracy and speed, and particularly to reverse the movement of a ramming ship to disentangle it from its sinking victim, lest it be pulled down when its victim sank. As galleys were intended to be fought from the bows, and were at their weakest along the sides, especially in the middle, the crescent formation employed by the Byzantines continued to be used throughout the Middle Ages. It would allow the wings of the fleet to crash their bows, with their ramming prows, straight into the sides of the enemy ships at the edge of the formation. You would try maneuver your ship into a position where you could ram the enemy ship to disable its mobility—in earlier centuries, the prow (the bettering ram jutting forward out of the bow of the ship) was under the water line, because the tactic was to ram a hole in the hull under the water line of the enemy ship, so that it would fill with water. In later centuries, the prow (battering ram) was at a certain height above the water level for the tactic then was to punch a hole in the hull at the level of the oars, so as immobilize the oarsmen and restrict the ships mobility. The speed necessary for a successful impact depended on the angle of attack; the greater the angle, the lesser the speed required. At 60 degrees, 4 knots was enough to penetrate the hull, but this increased to 8 knots at 30 degrees. If the target for some reason was in motion towards the attacker, less speed was required, especially if the hit came amidships. War galleys gradually began to develop heavier hulls with reinforcing beams at the waterline, where a ram would most likely hit. |

(5) One the enemy ship had been rammed (or if you decided not to or were unable to ram) you would seek to board the enemy ship by throwing across grappling-irons, in order to pull and fasten your boat to theirs, so that you could board them.

Artillery, on early gun galleys, was not used as a long-range standoff weapon against other gun-armed galleys. The maximum distance at which contemporary cannons were effective, being only 1,600 ft. or 300 yards, could be covered by a galley in about two minutes, much faster than the reload time of any artillery piece. Gun crews would therefore hold their fire until the last possible moment, somewhat similar to infantry tactics in the pre-industrial era of short range firearms. The guns on the bow (the front of the ship) would often be loaded with scatter shot and other anti-personnel ammunition. The effect of an assault with a gun-armed galley could often be dramatic, as exemplified by an account from 1528, where a galley of Genoese commander Antonio Doria, with a single volley from a basilisk, two demi-cannons and four smaller guns, killed 40 men. (6) Once you boarded (and they would also have their soldiers boarding your ship), you would try kill the enemy in hand-to-hand fighting—which could get very savage at times. The estimated average speed of Renaissance-era galleys was fairly low, only 3 to 4 knots, and a mere 2 knots when holding formation. Short bursts of up to 7 knots were possible for about 20 minutes, but only at the risk of exhausting rowers. This made galley actions relatively slow affairs, especially when they involved fleets of 100 vessels or more. The weak points of a galley remained the sides and especially the rear, which was the command center, and were therefore the preferred targets of any attacker. Unless one side managed to outmaneuver the other, battle would be met with ships crashing into each other head on. Once the fighting began with galleys locking on to one another bow to bow, the fighting would be over the front line ships. Unless one was completely taken over by a boarding party, fresh troops could be fed into the fight from reserve vessels in the rear. In a defensive position with a secure shoreline, galleys could be beached stern first with its guns pointing out to sea. This made for a very strong defensive position, allowed rowers and sailors to escape to safety on land, leaving only soldiers and fighting men to defend against an assault. So the requirements were speed to catch (or escape from) the enemy; some form of long-distance bombardment (until muskets, arquebuses, guns and cannon took over, it was the bow and arrow and the crossbow); an ability to ram and damage the enemy ship; troops to board and fight the enemy. These were the essential tactics and all the vessels carried a large number of troops, with swords, pikes, muskets, arquebuses, and bows and arrows and/or crossbows. The main purpose in later centuries was, if possible to capture the enemy ship rather than sink it—why not take a ship for free, tow it home, and make a few repairs, when it avoids having to build one! At times, however, the desire was destroy the enemy ship, and in this case ramming or trying to set the enemy ship on fire, by hurling incendiary missiles or by pouring the content of fire pots attached to long handles, is thought to have been used, especially since smoke below decks would easily disable rowers. |

Web Hosting by Just Host