| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON ANY EASTERTIDE LINK BELOW (all links are not yet activated)

| THE JOYS OF EASTER | EASTER DAILY THOUGHTS | VIRTUES FOR EASTER | EASTER SERMONS | THE RESURRECTION: WHAT HAPPENED NEXT? |

| EASTER WITH DOM GUERANGER | EASTER WITH AQUINAS | HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN | HISTORY OF RESURRECTIONS FROM THE DEAD |

| EASTER PRAYERS | EASTER LITURGY |

| THE JOYS OF EASTER | EASTER DAILY THOUGHTS | VIRTUES FOR EASTER | EASTER SERMONS | THE RESURRECTION: WHAT HAPPENED NEXT? |

| EASTER WITH DOM GUERANGER | EASTER WITH AQUINAS | HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN | HISTORY OF RESURRECTIONS FROM THE DEAD |

| EASTER PRAYERS | EASTER LITURGY |

WHY DOM GUÉRANGER? WHO IS DOM GUÉRANGER? WHAT IS SOLESMES?

The Liturgical Year (French: L'Année Liturgique) is a written work in fifteen volumes describing the liturgical year of the Catholic Church. The series was written by Dom Prosper Louis Pascal Guéranger, a French Benedictine priest and abbot of Solesmes. Dom Guéranger began writing the work in 1841, and died in 1875 after writing nine volumes. The remaining volumes were completed by another Benedictine under Dom Guéranger's name.

The series describes the liturgy of the Catholic Church throughout the liturgical year, including the Mass and the Divine Office. Also described is the historical development of the liturgy in both Western and Eastern traditions. Biographies of saints and their liturgies are given on their feast days.

The Liturgical Year has been likened to the "Summa Theologica" of St. Thomas Aquinas, which the Council of Trent placed alongside the Bible as a work of authority. Dom Guéranger's "The Liturgical Year" has thus been called the "Summa" of the liturgy of the Catholic Church. However, a word of warning to the reader, just like the :Summa Theologica", you will encounter some dry difficult parts (much like the Israelites in their forty years of penance in the desert), but there will also be found oases of deep spiritual refreshment. Persevere, read slowly, stop to think, and you will draw much fruit from this masterful work. Put away and put aside the modern-man's desire for fast-food, fast-service, being fast-tracked. There is no fast way of getting to Heaven (except for fasting perhaps!!). Besides, I don't think God appreciates being put quickly aside so that we can run off to do what we wrongly imagine to be "better" things. The season that we have entered should see us being more of a Mary than a Martha!

“Now it came to pass as they went, that Jesus entered into a certain town: and a certain woman named Martha, received Him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, who sitting also at the Lord’ s feet, heard his word. But Martha was busy about much serving. Who stood and said: ‘Lord, hast Thou no care that my sister hath left me alone to serve? speak to her therefore, that she help me!’ And the Lord answering, said to her: ‘Martha, Martha, thou art careful, and art troubled about many things: but one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her!’” (Luke 10:38-42).

The series describes the liturgy of the Catholic Church throughout the liturgical year, including the Mass and the Divine Office. Also described is the historical development of the liturgy in both Western and Eastern traditions. Biographies of saints and their liturgies are given on their feast days.

The Liturgical Year has been likened to the "Summa Theologica" of St. Thomas Aquinas, which the Council of Trent placed alongside the Bible as a work of authority. Dom Guéranger's "The Liturgical Year" has thus been called the "Summa" of the liturgy of the Catholic Church. However, a word of warning to the reader, just like the :Summa Theologica", you will encounter some dry difficult parts (much like the Israelites in their forty years of penance in the desert), but there will also be found oases of deep spiritual refreshment. Persevere, read slowly, stop to think, and you will draw much fruit from this masterful work. Put away and put aside the modern-man's desire for fast-food, fast-service, being fast-tracked. There is no fast way of getting to Heaven (except for fasting perhaps!!). Besides, I don't think God appreciates being put quickly aside so that we can run off to do what we wrongly imagine to be "better" things. The season that we have entered should see us being more of a Mary than a Martha!

“Now it came to pass as they went, that Jesus entered into a certain town: and a certain woman named Martha, received Him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, who sitting also at the Lord’ s feet, heard his word. But Martha was busy about much serving. Who stood and said: ‘Lord, hast Thou no care that my sister hath left me alone to serve? speak to her therefore, that she help me!’ And the Lord answering, said to her: ‘Martha, Martha, thou art careful, and art troubled about many things: but one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her!’” (Luke 10:38-42).

|

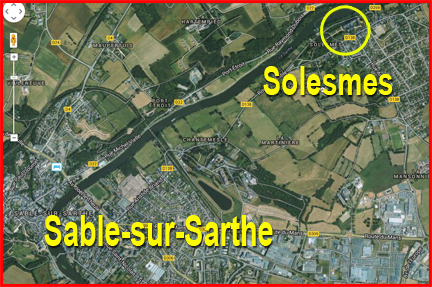

DOM GUÉRANGER & SOLESMES

Destined to be a Scholar, Priest and Monk, Dom Guéranger would begin his work in the aftermath of the French revolution, when religious life was effectively abolished in all of Europe. Aiming to restore all aspects of monastic life, the preservation of Gregorian chant - the sung liturgy of the church - would be an essential part of Dom Guéranger's goal. He would re-found the Abbey of St. Peter in Solesmes.

Dom Geuranger himself writes: “My youth, the complete lack of temporal resources, and the limited reliability of those with whom I hoped to associate — none of these things stopped me. I would not have dreamed of it; I felt myself pushed to proceed. I prayed with all my heart for the help of God; but it never occurred to me to ask His will concerning the projected work.”

That last statement may surprise us, but Dom Guéranger explains: “The need of the Church seemed to me so urgent, the ideas about true Christianity so falsified and so compromised in the lay and ecclesiastical worlds, that I felt nothing but an urgency to found some kind of center wherein to recollect and revive pure traditions.” Born in Sablé-sur-Sarthe, on April 4, 1805, Prosper Guéranger frequently made Solesmes the destination of his childhood walks, drawn by the charm of the church building and its life-sized saints in stone. Though as a child he never imagined himself a monk, he loved the solitude of the place. Aspiring first to the priesthood, a precocious vocation led him, after his high school studies in Angers, to the seminary in Le Mans. There, he was drawn intensely to the study of Church history, and soon he discovered what the institution of monasticism had been. Contact with the great scholarly works of the Maurists soon awoke in him a real desire for the monastic life.

Ordained a priest in 1827 (Guéranger was only 22 years old at the time, so that his bishop had to obtain a canonical dispensation), he pursued his work as the bishop's secretary in Paris and in Le Mans. In 1831, learning that the priory at Solesmes was destined to destruction for lack of a buyer, the idea came to him to find the means to acquire it and to take up the Benedictine life again. With the help of a few friends and encouraged by his bishop, he gathered together — with considerable difficulty — enough money to rent the monastery property, and subsequently moved in with three companions on July 11, 1833. The fledgling community encountered, of course, difficult times. But its young prior, borne up by his absolute confidence in Providence, by his humility and by his natural mirth and optimism, proved to possess a calm tenacity. Without copying the past in a servile way, he took inspiration from solid monastic traditions pursuing above all the true spirit of St Benedict while accepting several very necessary material adaptations to modern times. As a result, by his uncommon intuition of the benedictine charism, liturgy and spiritual life, he became a living example to his monks. As for temporal matters, Solesmes' first friends saw to the most urgent needs. They inaugurated a second and long list of the monastery's benefactors: the Cosnards, the Landeaus, the Gazeaus, Mme Swetchine, Montalembert, the Marquis of Juigné, and so many others who thought constantly of the monks.

After a four-year tryout Dom Guéranger went to Rome, in 1837, to ask the Vatican for official recognition of Solesmes as a benedictine community. Rome not only granted Dom Guéranger's request, but on its own initiative raised Solesmes from the status of priory to that of an abbey making it the head of a new Benedictine Congregation de France, successor to the Congregations of St. Maurus and St. Vanne as well as the more venerable and ancient family of monasteries belonging to Cluny. On July 26, Dom Guéranger made his solemn profession in the presence of the abbot of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. From then on began a new period in the history of Solesmes. |

THE LITURGICAL LIFE

Extracts from the Commentary on the Daily Liturgy by Dom Prosper Guéranger Article 1 : EASTER SUNDAY

"The Sabbath is Replaced by (Easter) Sunday" We give the name of Paschal Time to the period between Easter Sunday and the Saturday following Whit Sunday. It is the most sacred portion of the Liturgical Year, and the one towards which the whole Cycle converges. We shall easily understand how this is, if we reflect upon the greatness of the Easter Feast, which is called the Feast of Feasts, and the Solemnity of Solemnities, in the same manner, says St. Gregory, [Homilia, xxii.] as the most sacred part of the Temple was called the Holy of Holies; and the Book of Sacred Scripture, wherein are described the espousals between Christ and the Church, is called the Canticle of Canticles. It is on this day, that the mission of the Word Incarnate attains the object towards which it has hitherto been unceasingly tending: mankind is raised up from his fall, and regains what he had lost by Adam’s sin.

Christmas gave us a Man-God; three days have scarcely passed, since we witnessed His infinitely precious Blood shed for our ransom; but now, on the day of Easter, our Jesus is no longer the Victim of death: He is a Conqueror, that destroys death, the child of sin, and proclaims life, that undying life which He has purchased for us. The humiliation of His swathing-bands, the sufferings of His Agony and Cross, these are passed; all is now glory,- glory for Himself, and glory also for us. On the day of Easter, God regains, by the Resurrection of the Man-God, His creation such as He made it at the beginning; the only vestige now left of death, is that likeness to sin which the Lamb of God deigned to take upon Himself. Neither is it Jesus alone that returns to eternal life; the whole human race also has risen to immortality together with our Jesus. “By a man came death,” says the Apostle; “and by a Man the Resurrection of the dead: and as in Adam all die, so also in Christ all shall be made alive.” [1 Cor. xv. 21,22]. The anniversary of this Resurrection is, therefore, the great Day, the day of joy, the day par excellence; the day to which the whole year looks forward in expectation, and on which its whole economy is formed. But as it is the holiest of days,- since it opens to us the gate of Heaven, into which we shall enter because we have risen together with Christ,- the Church would have us come to it well prepared by bodily mortification and by compunction of heart. It was for this that she instituted the Fast of Lent, and that she bade us, during Septuagesima, look forward to the joy of her Easter, and be filled with sentiments suitable to the approach of so grand a solemnity. We obeyed; we have gone through the period of our preparation; and now the Easter sun has risen upon us! But it was not enough to solemnize the great Day when Jesus, our Light, rose from the darkness of the tomb: there was another anniversary which claimed our grateful celebration. The Incarnate Word rose on the first day of the week,- that same day, where on, four thousand years before, He, the Uncreated Word of the Father, had begun the work of the Creation, by calling forth light, and separating it from darkness. The first day was thus ennobled by the creation of light. It received a second consecration by the Resurrection of Jesus; and from that time forward Sunday, and not Saturday, was to be the Lord’s Day. Yes, our Resurrection in Jesus which took place on the Sunday, gave this first day a pre-eminence above the others of the week: the divine precept of the Sabbath was abrogated together with the other ordinances of the Mosaic Law, and the Apostles instructed the faithful to keep holy the first day of the week, which God had dignified with that twofold glory, the creation and the regeneration of the world. Sunday, then, being the day of Jesus’ Resurrection, the Church chose that day, in preference to every other, for its yearly commemoration. The Pasch of the Jews, in consequence of its being fixed on the fourteenth of the moon of March, (the anniversary of the going out of Egypt,) fell by turns on each day of the week. The Jewish Pasch was but a figure; ours is the reality, and puts an end to the figure. The Church, therefore, broke this her last tie with the Synagogue; and proclaimed her emancipation, by fixing the most solemn of her Feasts on a day, which should never agree with that on which the Jews keep their now unmeaning Pasch. The Apostles decreed, that the Christian Pasch should never be celebrated on the fourteenth of the moon of March, even were that day to be a Sunday; but that it should be everywhere kept on the Sunday following the day on which the obsolete calendar of the Synagogue still marks it. Nevertheless, out of consideration for the many Jews who had received Baptism, and who formed the nucleus of the early Christian Church, it was resolved that the law regarding the day for keeping the new Pasch, should be applied prudently and gradually. Jerusalem was soon to be destroyed by the Romans, according to our Savior’s prediction; and the new City, which was to rise up from its ruins and receive the Christian colony, would also have its Church, but a Church totally free from the Jewish element, which God had so visibly rejected. In preaching the Gospel and founding Churches, even far beyond the limits of the Roman Empire, the majority of the Apostles had not to contend with Jewish customs; most of their converts were from among the Gentiles. Article 2 : ARGUMENTS OVER THE DATE OF EASTER

"A Judaic Easter or a Gentile Easter? An Astronomical Problem!" Saint Peter, who in the Council of Jerusalem had proclaimed the cessation of the Jewish Law, set up the standard of emancipation in the City of Rome; so that the Church, which through him was made the Mother and Mistress of all Churches, never had any other discipline regarding the observance of Easter, than that laid down by the Apostles, namely, that it should be kept on a Sunday.

There was, however, one province of the Church, which for a long time stood out against the universal practice: it was Asia Minor. The Apostle St. John, who lived for many years at Ephesus -- where indeed he died -- had thought it prudent to tolerate, in those parts, the Jewish custom of celebrating the Pasch; for many of the converts had been members of the Synagogue. But the Gentiles themselves, who, later on, formed the mass of the faithful, were strenuous upholders of this custom, which dated from the very foundation of the Church of Asia Minor. In the course of time, however, this anomaly became a source of scandal: it savored of Judaism, and it prevented unity of religious observance, which is always desirable, but particularly so in what regards Lent and Easter. Pope St. Victor, who governed the Church from the year 193, endeavored to put a stop to this abuse; he thought the time had come for establishing unity in so essential a point of Christian worship. Already, that is in the year 160, under Pope St. Anicetus, the Apostolic See had sought, by friendly negotiations, to induce the Churches of Asia Minor to conform to the universal practice; but it was difficult to triumph over a prejudice, which rested on a tradition held sacred in that country. St. Victor, however, resolved to make another attempt. He would put before them the unanimous agreement which reigned throughout the rest of the Church. Accordingly, he gave orders, that Councils should be convened in the several countries where the Gospel had been preached, and that the question of Easter should be examined. Everywhere there was perfect uniformity of practice; and the historian Eusebius, who lived a hundred and fifty years later, assures us, that the people of his day used to quote the decisions of the Councils of Rome, of Gaul, of Achaia, of Pontus, of Palestine, and of Osrhoene in Mesopotamia. The Council of Ephesus, at which Polycrates, the Bishop of that city, presided, was the only one that opposed the Pontiff, and disregarded the practice of the universal Church. Deeming it unwise to give further toleration to the opposition, Victor separated from communion with the Holy See the refractory Churches of Asia Minor. This severe penalty, which was not inflicted until Rome had exhausted every other means of removing the evil, excited the commiseration of several Bishops. St. Irenaeus, who was then governing tile See of Lyons, pleaded for these Churches, which, so it seemed to him, had sinned only through a want of light; and he obtained from the Pope the revocation of a measure which seemed too severe. This indulgence produced the desired effect. In the following century, St. Anatolius, Bishop of Laodicea, in his Book on the Pasch, written in 276, tells us that the Churches of Asia Minor had then, for some time past, conformed to the Roman practice. About the same time, and by a strange co-incidence, the Churches of Syria, Cilicia. and Mesopotamia, gave scandal by again leaving the Christian and Apostolic observance of Easter, and returning to the Jewish rite of the fourteenth of the March moon. This Schism in the Liturgy grieved the Church; and one of the points to which the Council of Nicaea directed its first attention, was the promulgation of the universal obligation to celebrate Easter on the Sunday. The Decree was unanimously passed, and the Fathers of the Council ordained, that “all controversy being laid aside, the Brethren in the East should solemnize the Pasch on the same day as the Romans, the Alexandrians, and the rest of the faithful.” [Spicilegium Solesmense.] So important seemed this question, inasmuch as it affected the very essence of the Christian Liturgy, that St. Athanasius, assigning the reasons which had led to the calling of the Council of Nicaea, mentions these two: the condemnation of the Arian heresy, and the establishment of uniformity in the observance of Easter. [Epist. ad Afros Episcopos.] The Bishop of Alexandria was commissioned by the Council to see to the drawing up of astronomical tables, whereby the precise day of Easter might be fixed for each future year. The reason of this choice was, that the astronomers of Alexandria were looked upon as the most exact in their calculations. These tables were to be sent to the Pope, and he would address letters to the several Churches, instructing them as to the uniform celebration of the great Festival of Christendom. Thus was the unity of the Church made manifest by the unity of the holy Liturgy; and the Apostolic See, which is the foundation of the first, was likewise the source of the second. But, even previous to the Council of Nicaea, the Roman Pontiff had addressed to all the Churches, every year, a Paschal Encyclical, instructing them as to the day on which the solemnity of the Resurrection was to be kept. This we learn from the synodical Letter of the Fathers of the great Council held at Arles, in 314. The Letter is addressed to Pope St. Sylvester, and contains the following passage: “In the first place, we beg that the observance of the Pasch of the Lord may be uniform, both as to time and day, in the whole world, and that You would, according to the custom, address Letters to all concerning this matter.” [Concil. Galilae. t. 1]. This custom, however, was not kept up for any length of time, after the Council of Nicaea. The want of precision in astronomical calculations occasioned confusion in the method of fixing the day of Easter. It is true, this great Festival was always kept on a Sunday; nor did any Church think of celebrating it on the same day as the Jews; but, since there was no uniform understanding as to the exact time of the Vernal Equinox, it happened sane years, that the Feast of Easter was not kept., in all places, on the same day. By degrees, there crept in a deviation from the rule laid down by the Council, of taking the 21st of March as the day of the Equinox. There was needed a reform in the Calendar, and no one seemed competent to bring it about. Cycles were drawn up contradictory to one another; Rome and Alexandria had each its own system of calculation; so that, some years, Easter was not kept with that perfect uniformity which the Nicene Fathers had so strenuously labored for: and yet, this variation was not the result of anything like party-spirit. The West followed Rome. The Churches of Ireland and Scotland, which had been misled by faulty Cycles, were, at length, brought into uniformity. Finally, science was sufficiently advanced in the 16th century, for Pope Gregory XIII to undertake a reform of the Calendar. The Equinox had to be restored to the 21st of March, as the Council of Nicaea had prescribed. The Pope effected this by publishing a Bull, dated February 24, 1581, in which be ordered that ten days of the following year, namely from the 4th to the 15th of October, should be suppressed. He thus restored the work of Julius Caesar, who had, in his day, turned his attention to the rectification of the Year. Easter was the great object of the reform, or, as it is called, the New Style, achieved by Gregory XIII. The principles and regulations of the Nicene Council were again brought to bear on this the capital question of the Liturgical Year; and the Roman Pontiff thus gave to the whole world the intimation of Easter, not for one year only, but for centuries. Heretical nations were forced to acknowledge the divine power of the Church in this solemn act, which interested both religion and society. They protested against the Calendar, as they had protested against the Rule of Faith. England and the Lutheran States of Germany preferred following, for many years, a Calendar which was evidently at fault, rather than accept the New Style, which they acknowledged to be indispensable; but it was the work of a Pope! [Great Britain adopted the New Style, by Act of Parliament, in the year 1732]. The only nation in Europe that keeps up the Old Style is Russia, whose antipathy to Rome obliges her to be thus ten or twelve days behind the rest of the civilized world. Article 3 : ARGUMENTS OVER THE DATE OF EASTER

"Easter Vigil Water Font Miracles" (continuation of the theme from the previous article) All this shows us how important it was to fix the precise day of Easter; and God has several times shown by miracles, that the date of so sacred a Feast was not a matter of indifference. During the ages when the confusion of the Cycles and the want of correct astronomical computations occasioned great uncertainty as to the Vernal Equinox, miraculous events more than once supplied the deficiencies of science and authority. In a letter to St. Leo the Great, in the year 444, Paschasinus, Bishop of Lilybea [modern Marsala] in Sicily, relates that under the Pontificate of St. Zozinius ― Honorius being Consul for the eleventh, and Constantius for the second time― the real day of Easter was miraculously revealed to the people of one of the churches there. In the midst of a mountainous and thickly wooded district of the Island was a village called Meltinas. Its church was of the poorest, but it was dear to God.

Every year, on the night preceding Easter Sunday, as the Priest went to the Baptistery to bless the Font, it was found to be miraculously filled with water, for there were no human means wherewith it could be supplied. As soon as Baptism was administered, the water disappeared of itself, and left the Font perfectly dry. In the year just mentioned, the people, misled by a wrong calculation, assembled for the ceremonies of Easter Eve. The Prophecies having been read, the Priest and his flock repaired to the Baptistery―but the Font was empty. They waited, expecting the miraculous flowing of the water, wherewith the Catechumens were to receive the grace of regeneration: but they waited in vain, and no Baptism was ad ministered. On the following 22nd of April, the Font was found to be filled to the brim, and thereby the people understood that that was the true Easter for that year. [Sti. Leonis Opera, Epist. iii.] Cassiodorus, writing in the name of king Athalaric to a certain Severus, relates a similar miracle, which happened every year on Easter Eve, in Lucania, near the small Island of Leucothea, at a place called Marcilianum. There was a large fountain there, whose water was so clear, that the air itself was not more transparent. It was used as the Font for the administration of Baptism on Easter Night. As soon as the Priest, standing under the rock where with nature had canopied the fountain, began the prayers of the Blessing, the water, as though taking part in the transports of the Easter joy, arose in the Font; so that, if previously it was to the level of the fifth step, it was seen to rise up to the seventh, impatient, as it were, to effect those wonders of grace whereof it was the chosen instrument. God would show by this, that even inanimate creatures can share, when He so wills it, in the holy gladness of the greatest of all days. [Cassiodorus, Variarum, lib. vii. epist. xxxiii.] St. Gregory of Tours tells us of a Font, which existed even then, in a church of Andalusia, in a place called Osen, and whereby God miraculously certified to His people the true day of Easter. On the Maundy Thursday of each year, the Bishop, accompanied by the faithful, repaired to this church. The bed of the Font was built in the form of a cross, and was paved with mosaics. It was carefully examined, to see that it was perfectly dry; and after several prayers had been recited, every one left the church, and the Bishop sealed the door with his seal. On Holy Saturday the Pontiff returned, accompanied by his flock; the seal was examined, and the door was opened. The Font was found to be filled, even above the level of the floor, and yet the water did not overflow. The Bishop pronounced the exorcisms over the miraculous water, and poured the Chrism into it. The Catechumens were then baptized; and as soon as the sacrament had been administered, the water immediately disappeared, and no one could tell what became of it. [De Gloria Martyrum, lib. i. Cap. xxiv.] Similar miracles were witnessed in several churches in the East. John Moschus, a writer in the 7th century, speaks of a Baptismal Font in Lycia, which was thus filled every Easter Eve; hut the water remained in the Font during the whole fifty days, and suddenly disappeared after the Festival of Pentecost. [Pratum spirituale, cap. ccxv.] We alluded, in our History of Passiontide, to the decrees passed by the Christian Emperors, which forbade all law proceedings during the fortnight of Easter, that is, from Palm Sunday to the Octave day of the Resurrection. St. Augustine, in a sermon he preached on this Octave, exhorts the faithful to extend to the whole year this suspension of law-suits, disputes, and enmities, which the civil law interdicted during these fifteen days. The Church puts upon all her children the obligation of receiving Holy Communion at Easter. This precept is based upon the words of our Redeemer, who left it to His Church to determine the time of the year, when Christians should receive the Blessed Sacrament. In the early ages, Communion was frequent, and, in some places, even daily. By degrees, the fervor of the faithful grew cold towards this august Mystery, as we gather from a decree of the Council of Agatha (Agde), held in 506, where it is defined, that those of the laity who shall not approach Communion at Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, are to be considered as having ceased to be Catholics. [Concil. Agath. Canon xviii.] This Decree of the Council of Agatha was accepted as the law of almost the entire Western Church. We find it quoted among the regulations drawn up by Egbert, Archbishop of York, as also in the third Council of Tours. In many places, however, Communion was obligatory for the Sundays of Lent, and for the last three days of Holy Week, independently of that which was to be made on the Easter Festival. Article 4 : THE ANNUAL OBLIGATORY HOLY COMMUNION

"Holy Communion and Other Easter Practices" It was in the year 1215, in the 4th General Council of Lateran, that the Church, seeing the ever growing indifference of her children, decreed with regret that Christians should be strictly bound to Communion only once in the year, and that that Communion of obligation should be made at Easter. In order to show the faithful that this is the uttermost limit of her condescension to lukewarmness, she declares, in the same Council, that he that shall presume to break this law, may be forbidden to enter a church during life, and he deprived of Christian burial after death, as he would be if he had, of his own accord, separated himself from the exterior link of Catholic unity.

[Two centuries after this, Pope Eugenius the Fourth, in the Constitution Digna Fide, given in the year 1440, allowed this annual Communion to be made on any day between Palm Sunday and Low Sunday inclusively. In England, by permission of the Holy See, the time for making the Easter Communion extends from Ash Wednesday to Low Sunday]. These regulations of a General Council show how important is the duty of the Easter Communion; but, at the same time, they make us shudder at the thought of the millions, throughout the Catholic world, who brave each year the threats of the Church, by refusing to comply with a duty, which would both bring life to their souls, and serve as a profession of their faith. And when we again reflect upon how many even of those who make their Easter Communion, have paid no more attention to the Lenten Penance than if there were no such obligation in existence, we cannot help feeling sad, and we wonder within ourselves, how long God will bear with such infringements of the Christian Law? The fifty days between Easter and Pentecost have ever been considered by the Church as most holy. The first week, which is more expressly devoted to celebrating our Lord’s Resurrection, is kept up as one continued Feast; but the remainder of the fifty days is also marked with special honors. To say nothing of the joy, which is the characteristic of this period of the year, and of which the Alleluia is the expression,- Christian tradition has assigned to Eastertide two practices, which distinguish it from every other Season. The first is, that fasting is not permitted during the entire interval: it is an extension of the ancient precept of never fasting on a Sunday, and the whole of Eastertide is considered as one long Sunday. This practice, which would seem to have come down from the time of the Apostles, was accepted by the Religious Rules of both East and West, even by the severest. The second consists in not kneeling at the Divine Office, from Easter to Pentecost. The Eastern Churches have faithfully kept up the practice, even to this day. It was observed for many ages by the Western Churches also; but now, it is little more than a remnant. The Latin Church has long since admitted genuflections in the Mass during Easter time. The few vestiges of the ancient discipline in this regard, which still exist, are not noticed by the faithful, inasmuch as they seldom assist at the Canonical Hours. Eastertide, then, is like one continued Feast. It is the remark made by Tertullian, in the 3rd century. He is reproaching those Christians who regretted having renounced, by their Baptism, the festivities of the pagan year; and he thus addresses them: "If you love Feasts, you will find plenty among us Christians; not merely Feasts that last only for a day, but such as continue for several days together. The Pagans keep each of their Feasts once in the year; but you have to keep each of yours many times over, for you have the eight days of its celebration. Put all the Feasts of the Gentiles together, and they do not amount to our fifty days of Pentecost." [De Idolatria, cap. xiv.] St. Ambrose speaking on the same subject, says: "If the Jews are not satisfied with the Sabbath of each week, but keep also one which lasts a whole month, and another which lasts a whole year;- how much more ought not we to honor our Lord’s Resurrection? Hence our ancestors have taught us to celebrate the fifty days of Pentecost as a continuation of Easter. They are seven weeks, and the Feast of Pentecost commences the eighth. ... During these fifty days, the Church observes no fast, as neither does she on any Sunday, for it is the day on which our Lord rose: and all these fifty days are like so many Sundays." [In Lucam, lib. viii. cap. xxv.] Article 5 : THE MYSTERY OF PASCHAL TIME

"The Greatest and Richest Season of the Year" Of all the Seasons of the Liturgical Year, Eastertide is by far the richest in mystery. We might even say that Easter is the summit of the Mystery of the sacred Liturgy. The Christian who is happy enough to enter, with his whole mind and heart, into the knowledge and the love of the Paschal Mystery, has reached the very center of the supernatural life. Hence it is, that the Church uses every effort in order to effect this: what she has hitherto done, was all intended as a preparation for Easter. The holy longings of Advent, the sweet joys of Christmas, the severe truths of Septuagesima, the contrition and penance of Lent, the heart-rending sight of the Passion, all were given us as preliminaries, as paths, to the sublime and glorious Pasch, which is now ours.

And that we might be convinced of the supreme importance of this Solemnity, God willed that the Christian Easter and Pentecost should be prepared by those of the Jewish Law: a thousand five hundred years of typical beauty prefigured the reality: and that reality is ours! During these days, then, we have brought before us the two great manifestations of God’s goodness towards mankind—the Pasch of Israel, and the Christian Pasch; the Pentecost of Sinai, and the Pentecost of the Church. We shall have occasion to show how the ancient figures were fulfilled in the realities of the new Easter and Pentecost, and how the twilight of the Mosaic Law made way for the full lay of the Gospel; but we cannot resist the feeling of holy reverence, at the bare thought that the Solemnities we have now to celebrate are more than three thousand years old, and that they are to be renewed every year from this till the Angel shall be heard proclaiming: “Time shall be no more!” The gates of eternity will then be thrown open. Eternity in Heaven is the true Pasch: hence, our Pasch, here on earth, is the Feast of feasts, the Solemnity of solemnities. The human race was dead; it was the victim of that sentence, whereby it was condemned to be mere dust in the tomb; the gates of life were shut against it. But see the Son of God rises from His grave and takes possession of eternal life. Nor is He the only one that is to die no more, for, as the Apostle teaches us, He is the. first-born from the dead. The Church would, therefore, have us consider ourselves as having already risen with our Jesus, and as having already taken possession of eternal life. The holy Fathers bid us look on these fifty days of Easter, as the image of our eternal happiness. They are days devoted exclusively to joy; every sort of sadness is forbidden; and the Church cannot speak to her divine Spouse without joining to her words that glorious cry of heaven, the Alleluia, wherewith, as the holy Liturgy says, the streets and squares of the heavenly Jerusalem resound without ceasing. We have been forbidden the use of this joyous word during the past nine weeks; it behooved us to die with Christ: but now that we have risen together with Him, from the tomb, and that we are resolved to die no more that death, which kills the soul, and called our Redeemer to die on the Cross, we have a right to our Alleluia. The Providence of God, who has established harmony between the visible world and the supernatural work of grace, willed that the Resurrection of our Lord should take place at that particular season of the year, when even nature herself seems to rise from the grave. The meadows give forth their verdure, the trees resume their foliage, the birds fill the air with their songs, and the sun, the type of our triumphant Jesus, pours out his floods of light on our earth made new by lovely Spring. At Christmas, the sun had little power, and his stay with us was short; it harmonized with the humble birth of our Emmanuel, who came among us in the midst of night, and shrouded in swaddling clothes ; but now, He is “as a giant that runs his way, and there is no one that can hide himself from his heat” (Psalm 18:6-7). Speaking, in the Canticle, to the faithful soul, and inviting her to take her part in this new life which He is now imparting to every creature, our Lord Himself says: “Arise, my dove, and come! Winter is now past, the rain is over and gone. The flowers have appeared in our land. The voice of the turtle is heard. The fig-free hath put forth her green figs. The vines, in flower, yield their sweet smell. Arise thou, and come!” (Canticles 2:10, 13). Article 6 : THE MYSTERY OF PASCHAL DAYS AND NUMBERS

"From Sabbath to Sunday" Earlier, we explained why our Savior chose the Sunday for His Resurrection, whereby He conquered death and proclaimed life to the world. It was on this favored day of the week, that He had, four thousand years previously, created the light; by selecting it now for the commencement of the new life He graciously imparts to man, He would show us that Easter is the renewal of the entire creation. Not only is the anniversary of His glorious Resurrection to be, henceforward, the greatest of days, but every Sunday throughout the year is to be a sort of Easter, a holy and sacred day.

The Synagogue, by God’s command, kept holy the Saturday, or the Sabbath, and this in honor of God’s resting after the six days of the creation; but the Church, the Spouse, is commanded to honor the Work of her Lord. She allows the Saturday to pass, it is the day her Jesus rested in the Sepulcher: but, now that she is illumined with the brightness of the Resurrection, she devotes to the contemplation of His Work the first day of the week; it is the day of light, for on it He called forth material light (which was the first manifestation of life upon chaos), and on the same, He that is the “Brightness of the Father” (Hebrews 1:5) and “the Light of the world” (John 8:12), rose from the darkness of the tomb. Let, then, the week with its Sabbath pass by; what we Christians want is the eighth day, the day that is beyond the measure of time, the day of eternity, the day whose light is not intermittent or partial, but endless and unlimited. Thus speak the holy Fathers, when explaining the substitution of the Sunday for the Saturday. It was, indeed, right that man should keep, as the day of his weekly and spiritual repose, that on which the Creator of the visible world had taken His divine rest; but it was a commemoration of the material creation only. The Eternal Word comes down in the world that He has created; He comes with the rays of His divinity clouded beneath the humble veil of our flesh; He comes to fulfill the figures of the first Covenant. Before abrogating the Sabbath, He would observe it, as He did every tittle of the Law; He would spend it as the day of rest, after the work of His Passion, in the silence of the Sepulcher: but, early on the eighth day, He rises to life, and the life is one of glory. “Let us,” says the learned and pious Abbot Rupert, “leave the Jews to enjoy the ancient Sabbath, which is a memorial of the visible creation. They know not how to love or desire or merit anything but earthly things ... They would not recognize this world’s Creator as their King, because He said: ‘Blessed are the poor!’ and, ‘Woe to the rich!’ But our Sabbath has been transferred from the seventh to the eighth day, and the eighth is the first. And rightly was the seventh changed into the eighth, because we Christians put our joy in a better work than the creation of the world. Let the lovers of the world keep a Sabbath for its creation: but our joy is in the salvation of the world, for our life, yea, and our rest, is hidden with Christ in God.” The mystery of the seventh followed by an eighth day, as the holy one, is again brought before us by the number of weeks, which form Eastertide. These weeks are seven; they form a week of weeks, and their morrow is again a Sunday, the Feast of the glorious Pentecost. These mysterious numbers— which God Himself fixed, when He instituted the first Pentecost after the first Pasch—were followed by the Apostles, when they regulated the Christian Easter, as we learn from St. Hilary of Poitiers, St. Isidore, Amalarius, Rabanus Maurus, and from all the ancient interpreters of the mysteries of the holy Liturgy. “If we multiply seven by seven,” says St. Hilary, “We shall find that this holy Season is truly the Sabbath of sabbaths; but what completes it, and raises it to the plenitude of the Gospel, is the eighth day which follows, eighth and first both together in itself. The Apostles have given so sacred an institution to these seven weeks that, during then no one should kneel, or mar by fasting the spiritual joy of this long Feast. The same institution has been extended to each Sunday; for this day which follows the Saturday has become, by the application of the progress of the Gospel, the completion of the Saturday, and the day of feast and joy.” Thus, then, the whole Season of Easter is marked with the mystery expressed by each Sunday of the year. Sunday is to us the great day of our wed because beautified with the splendor of our Lord’ Resurrection, of which the creation of material ugh was but a type. We have already said that the institution was prefigured in the Old Law, although the Jewish people were not in any way aware of ii Their Pentecost fell on the fiftieth day after the Pasch it was the morrow of the seven weeks. Article 7 : THE CUSTOMS AND PRACTICES OF EASTERTIDE

"After Mourning for Sin, We Rejoice In the Mercy of God" The rites peculiar to Eastertide, in the present discipline of the Church, are two: the unceasing repetition of the Alleluia, of which we have already spoken and the color of the Vestments used for its two great solemnities, white for the first, and red for the second. White is appropriate to the Resurrection; it is the mystery of eternal light, which knows neither spot nor shadow; it is the mystery that produces in a faithful soul the sentiment of purity and joy. Pentecost, which gives us the Holy Spirit, the “consuming Fire” (Hebrews 12:29), is symbolized by the red vestments, which express the mystery of the Divine Paraclete coming down iii the form of fiery tongues upon them that were assembled in the Cenacle. With regard to the ancient usage of not kneeling during Paschal Time, we have already said, that there is a mere vestige of it now left in the Latin Liturgy.

The Saints’ Feasts, which were interrupted during Holy Week, are likewise excluded from the first eight days of Eastertide; but these ended, we shall have them in rich abundance, as a bright constellation of stars round the divine Sun of Justice, our Jesus. They will accompany us in our celebration of His admirable Ascension; but such is the grandeur of the mystery of Pentecost, that, from the eve of that day, they will be again interrupted until the expiration of Paschal Time. The rites of the primitive Church with reference to the Neophytes, who were regenerated by Baptism on the night of Easter, are extremely interesting and instructive, but, as they are peculiar to the two Octaves of Easter and Pentecost, we will explain them as they are brought before us by the Liturgy of those days. The practice for this holy Season mainly consists in the spiritual joy, which it should produce in every soul that is risen with Jesus. This joy is a foretaste of eternal happiness, and the Christian ought to consider it a duty to keep it up within him, by ardently seeking after that life which is in our divine Head, and by carefully shunning sin which causes death. During the last nine weeks, we have mourned for our sins and done penance for them; we have followed Jesus to Calvary; but now, our holy Mother the Church is urgent in bidding us rejoice. She herself has laid aside all sorrow; the voice of her weeping is changed into the song of a delighted Spouse. In order that she might impart this joy to all her children, she has taken their weakness into account. After reminding them of the necessity of expiation, she gave them forty days wherein to do penance; and. then, taking off all the restraint of Lenten mortification, she brings us to Easter as to a land where there is nothing but gladness, light, life, joy, calm, and the sweet hope of immortality. Thus does she produce, in those of her children who have no elevation of soul, sentiments in harmony with the great Feast, such as the most perfect feel; and by this means, all, both fervent and tepid, unite their voices in one same hymn of praise to our risen Jesus. The great Liturgist of the 12th century, Rupert, Abbot of Deutz, thus speaks of the pious artifice used by the Church to infuse the spirit of Easter into all: “There are certain carnal minds, that seem unable to open their eyes to spiritual things, unless roused by some unusual excitement; and for this reason, the Church makes use of such means. Thus, the Lenten Fast. which we offer up to God as our yearly tithe, goes on till the most sacred night of Easter; then follow fifty days without so much as one single Fast.. Hence it happens, that while the body is being mortified, and is to continue to be so till Easter Night, that holy night is eagerly looked forward to even by the carnal-minded; they long for it to come; and, meanwhile, they carefully count each of the forty days, as a wearied traveler does the miles. Thus, the sacred Solemnity is sweet to all, and dear to all, and desired by all, as light is to them that walk in darkness, as a fount of living water is to them that thirst, and as “a tent which the Lord hath pitched” for wearied wayfarers.” What a happy time was that, when, as St. Bernard expresses it, there was not one in the whole Christian army, that neglected his Easter duty, and when all, both just and sinners, walked together in the path of the Lenten observances! Alas those days are gone, and Easter has not the same effect on the people of our generation! The reason is that a love of ease and a false conscience lead so many Christians to treat the law of Lent with as much indifference, as though there were no such law existing. Hence, Easter Comes upon them as a Feast—it may be as a great Feast―but that is all. They experience little of that thrilling joy which fills the heart of the Church hiring this Season, and which she evinces in everything she does. And if this be their case even on the glorious day itself, how can it be expected that they should keep up, for the whole fifty, the spirit of gladness, which is the very essence of Easter? They have not observed the fast, or the abstinence, of Lent: the mitigated form in which the Church now presents them to her children, in consideration of their weakness, was too severe for them! They sought, or they took, a total dispensation from this law of Lenten mortification, and without regret or remorse. The Alieluia returns, and it finds no response in their souls: how could it? Penance has not done its work of purification; it has not spiritualized them ; how, then, could they follow their risen Jesus, whose life is henceforth more of Heaven than of Earth? But these reflections are too sad for such a Season as this: let us beseech our risen Jesus to enlighten these souls with the rays of His victory over the world and the flesh, and to raise them up to Himself. No, nothing must now distract us from joy. “Can the children of the Bridegroom mourn, as long as the Bridegroom is with them?” (Collect for Tuesday in Easter Week. Romans 6:6). Jesus is to be with us for forty days; He is to suffer no more, and die no more; let our feelings be in keeping with His: now endless glory and bliss. True, He is to leave us, He is to ascend to the right hand of His Father; but He will not leave us orphans; He will send us the divine Comforter, who will abide with us forever (Romans 6:4). These sweet and consoling words must be our Easter text: “The children of the Bridegroom cannot mourn, as long as the Bridegroom is with us.” They are the key to the whole Liturgy of this holy Season. We must have them ever before us, and we shall find by experience, that the joy of Easter is as salutary as the contrition and penance of Lent. Jesus on the Cross, and Jesus in the Resurrection, it is ever the same Jesus; but what He wants from us now, is that we should keep near Him, in company with His blessed Mother, His disciples, and Magdalene, who are in ecstasies of delight at His triumph, and have forgotten the sad days of His Passion. But this Easter of ours will have an end; the bright vision of our risen Jesus will pass away; and all that will be left to us, is the recollection of His ineffable glory, and of the wonderful familiarity wherewith He treated us. What shall we do, when He who was our very life arid light, leaves us, and ascends to Heaven? Be of good heart, Christians! You must look forward to another Easter. Each year will give you a repetition of what you now enjoy. Easter will follow Easter, and bring you at last to that Easter in Heaven, which is never to have an end, and of which these happy ones of Earth are a mere foretaste. Nor is this all! Listen to the Church. In one of her Prayers she reveals to us the great secret, how we may perpetuate our Easters even here in our banishment: “Grant to thy servants, O God, that they may keep up, by their manner of living, the Mystery they have received by believing!” So, then, the Mystery of Easter is to be ever visible on this Earth; our risen Jesus ascends to Heaven, hut He leaves upon us the impress of His Resurrection and we must retain it within us until He again visits us. Article 8 : THE MEANING OF THE RESURRECTION FOR US

"Retaining the Stamp of the Resurrection " Our risen Lord, even when He ascends to Heaven, leaves behind the stamp of His Resurrection upon us and we must retain it within us until He again visits us. And how could it be that we should not retain this divine stamp or impression within us? Are not all the mysteries of our divine Master ours also? From His very first coming in the Flesh, He has made us sharers in everything He has done. He was born in Bethlehem: we were born together with Him. He was crucified: our “old man was crucified with Him” (Romans 6:6). He was buried: we were buried with Him (Romans 6:4).

And therefore, when He rose from the grave, we also received the grace that we should ‘walk in the newness of life.” Such is the teaching of the Apostle, who thus continues: “We know that Christ rising again from the dead, dieth now no more; death shall no more have dominion over Him: for in that He died to sin, (that is, for sin,) He died once; but in that He liveth, He liveth unto God” (Romans 6:9-10). He is our head, and we are His members: we share in what is His. To die again by sin, would be to renounce Him, to separate ourselves from Him, to forfeit that Death and Resurrection of His, which He mercifully willed should be ours. Let us, therefore, preserve within us that life, which is the life of our Jesus, and yet, which belongs to us as our own treasure; for lie won it by conquering death, and then gave it to us, with all His other merits. You, then, who before Easter were sinners, but have now returned to the life of grace, see that you die no more; let your actions bespeak your resurrection. And you, to whom the Paschal Solemnity has brought growth in grace, show this increase of more abundant life by your principles and your conduct. It is thus all will “walk in the newness of life” (Romans 6:4).. With this, for the present, we take leave of the lessons taught us by the Resurrection of Jesus; the rest we reserve for the humble commentary we shall have to make on the Liturgy of tills holy season. We shall then see, more and more clearly, not only our duty of imitating our divine Master’s Resurrection, but the in magnificence of this grandest Mystery of the Man-God. Easter—with its three admirable manifestations of divine love and power, the Resurrection, the Ascension, and the Descent of the Holy Ghost,—yes, Easter is the perfection of the work of our Redemption. Everything, both in the order of time and in the workings of the Liturgy, has been a preparation for Easter. The four thousand years that followed the promise made by God to our First Parents, were crowned by the event that we are now to celebrate. All that the Church has been doing for us from the very commencement of Advent, had this same glorious event in view; and now that we have come to it, our expectations are more than realized, and the power and wisdom of God are brought before us so vividly, that our former know ledge of them seems nothing in comparison with our present appreciation and love of them. The Angels themselves are dazzled by the grand Mystery, as the Church tells us in one of her Easter Hymns, where she says: “The Angels gaze with wonder on the change wrought in mankind: it was flesh that sinned, and now Flesh taketh all sin away, and the God that reigns is the God made Flesh.” Eastertide, too, belongs to what is called the Illuminative Life; nay, it is the most important part of that life, for it not only manifests, as the last four seasons of the Liturgical year have done, the humiliations and the sufferings of the Man-God: it shows Him to us in all His grand glory; it gives us to see Him expressing in His own sacred Humanity, tile highest degree of the creature’s transformation into his God. The Corning of the Holy Ghost will bring additional brightness to this Illumination; it shows us the relations that exist between the soul and the Third Person of the Blessed Trinity. And here we see the way and the progress of a faithful soul. She was made an adopted child of the Heavenly Father; she was initiated into all the duties and mysteries of her high vocation, by the lessons and examples of the Incarnate Word; she was perfected, by the visit and indwelling of the Holy Ghost. From this there result those several Christian exercises, which produce within her an imitation of her divine Model, amid prepare her for that Union, to which she is invited by Him, who “gave to them that received Him, power to be made sons of God,” by a birth that is “not of blood, nor of the flesh, but of God” (John 1:12-13). Article 9 : THOUGHTS FOR THE WEEK OF LOW SUNDAY

"Mercy on the Doubters" Our neophytes closed the Octave of the Resurrection yesterday. They were before us in receiving the admirable Mystery; their solemnity would finish earlier than ours. This, then, is the eighth day for us who kept the Pasch on the Sunday, and did not anticipate it on the vigil. It reminds us of all the glory and joy of that feast of feasts, which united the whole of Christendom in one common feeling of triumph. It is the day of light, which takes the place of the Jewish Sabbath.

Henceforth, the first day of the week is to be kept holy. Twice has the Son of God honored it with the manifestation of His almighty power. The Pasch, therefore, is always to be celebrated on the Sunday; and thus every Sunday becomes a sort of Paschal feast, as we have already explained in the Mystery of Easter. Our risen Jesus gave an additional proof that He wished the Sunday to be, henceforth, the privileged day. He reserved the second visit He intended to pay to all His disciples for this the eighth day since His Resurrection. During the previous days, He has left Thomas a prey to doubt; but today He shows Himself to this Apostle, as well as to the others, and obliges him, by irresistible evidence, to lay aside his incredulity. Thus does our Savior again honor the Sunday. The Holy Ghost will come down from heaven upon this same day of the week, making it the commencement of the Christian Church: Pentecost will complete the glory of this favored day. Jesus’ apparition to the eleven, and the victory he gains over the incredulous Thomas―these are the special subjects the Church brings before us today. By this apparition, which is the seventh since His Resurrection, our Savior wins the perfect faith of His disciples. It is impossible not to recognize God in the patience, the majesty, and the charity of Him who shows himself to them. Here, again, our human thoughts are disconcerted; we should have thought this delay excessive; it would have seemed to us that our Lord ought to have at once either removed the sinful doubt from Thomas’s mind, or punished him for his disbelief. But no: Jesus is infinite wisdom, and infinite goodness. In His wisdom, He makes this tardy acknowledgement of Thomas become a new argument of the truth of the Resurrection; in His goodness, He brings the heart of the incredulous disciple to repentance, humility, and love; yea, to a fervent and solemn retraction of all his disbelief. We will not here attempt to describe this admirable scene, which holy Church is about to bring before us. We will select, for our today’s instruction, the important lesson given by Jesus to His disciple, and through him to us all. It is the leading instruction of the Sunday, the Octave of the Pasch, and it behooves us not to pass it by, for, more than any other, it tells us the leading characteristic of a Christian, shows us the cause of our being so listless in God’s service, and points out to us the remedy for our spiritual ailments. Jesus says to Thomas: “Because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and have believed!” Such is the great truth, spoken by the lips of the God-Man: it is a most important counsel, given, not only to Thomas, but to all who would serve God and secure their salvation. What is it that Jesus asks of His disciple? Has He not heard him make profession that now, at last, he firmly believes? After all, was there any great fault in Thomas’s insisting on having experimental evidence before believing in so extraordinary a miracle as the Resurrection? Was he obliged to trust to the testimony of Peter and the others, under penalty of offending his divine Master? Did he not manifest his prudence, by withholding his assent until he had additional proofs of the truth of what his brethren told him? Yes, Thomas was a circumspect and prudent man, and one that was slow to believe what he had heard; he was worthy to be taken as a model by those Christians who reason and sit in judgement upon matters of faith. And yet, listen to the reproach made him by Jesus. It is merciful, and withal so severe! Jesus has so far condescended to the weakness of His disciple as to accept the condition on which alone he declares that he will believe: now that the disciple stands trembling before his risen Lord, and exclaims, in the earnestness of faith, “My Lord and my God!” Oh! See how Jesus chides him! This stubbornness, this incredulity, deserves a punishment: the punishment is, to have these words said to him: “Thomas! Thou hast believed, because thou hast seen!” Then was Thomas obliged to believe before having seen? Yes, undoubtedly! Not only Thomas, but all the Apostles were in duty bound to believe the Resurrection of Jesus, even before He showed himself to them. Had they not lived three years with Him? Had they not seen Him prove Himself to be the Messias and the Son of God by the most undeniable miracles? Had he not foretold them that he would rise again on the third day? As to the humiliations and cruelties of His Passion, had He not told them, a short time previous to it, that He was to be seized by the Jews in Jerusalem, and be delivered to the Gentiles? That He was to be scourged, spat upon, and put to death? (Luke 18:32-33). After all this, they ought to have believed in His triumphant Resurrection, the very first moment they heard of His Body having disappeared. As soon as John had entered the sepulcher, and seen the winding-sheet, he at once ceased to doubt; he believed. But it is seldom that man is so honest as this; he hesitates, and God must make still further advances, if he would have us give our faith! Jesus condescended even to this: He made further advances. He showed himself to Magdalen and her companions, who were not incredulous, but only carried away by natural feeling, though the feeling was one of love for their Master. When the Apostles heard their account of what had happened, they treated them as women whose imagination had got the better of their judgement. Jesus had to come in person: He showed Himself to these obstinate men, whose pride made them forget all that He had said and done, sufficient indeed to make them believe in his Resurrection. Yes, it was pride―for faith has no other obstacle than this. If man were humble, he would have faith enough to move mountains. Article 10 : THOUGHTS FOR THE WEEK OF LOW SUNDAY

"Don't Doubt You Could Become A Doubter!" To return to our Apostle. Thomas had heard Magdalen, and he despised her testimony; he had heard Peter, and he objected to his authority; he had heard the rest of his fellow-Apostles and the two disciples of Emmaus, and no, he would not give up his own opinion. How many there are among us who are like him in this! We never think of doubting what is told us by a truthful and disinterested witness, unless the subject touch upon the supernatural; and then we have a hundred difficulties.

It is one of the sad consequences left in us by Original Sin. Like Thomas, we would see the thing ourselves: and that alone is enough to keep us from the fullness of the truth. We comfort ourselves with the reflection that, after all, we are disciples of Christ; as did Thomas, who kept in union with his brother-Apostles, only he shared not their happiness. He saw their happiness, but he considered it to be a weakness of mind, and was glad that he was free from it! How like this is to our modern rationalistic Catholic! He believes, but it is because his reason almost forces him to believe; he believes with his mind, rather than from his heart. His Faith is a scientific deduction, and not a generous longing after God and supernatural truth. Hence how cold and powerless is this Faith! How cramped and ashamed! How afraid of believing too much! Unlike the generous unstinted Faith of the saints, it is satisfied with fragments of truth, with what the Scripture terms diminished truths. It seems ashamed of itself. It speaks in a whisper, lest it should be criticized; and when it does venture to make itself heard, it adopts a phraseology which may take off the sound of the divine. As to those miracles which it wishes had never taken place, and which it would have advised God not to work, they are a forbidden subject. The very mention of a miracle, particularly if it have happened in our own times, puts it into a state of nervousness. The lives of the saints, their heroic virtues, their sublime sacrifices―it has a repugnance to the whole thing! It talks gravely about those who are not of the true religion being unjustly dealt with by the Church in Catholic countries; it asserts that the same liberty ought to be granted to error as to truth; it has very serious doubts whether the world has been a great loser by the secularization of society. Now it was for the instruction of persons of this class that our Lord spoke those words to Thomas: “Blessed are they who have not seen, and have believed.” Thomas sinned in not having the readiness of mind to believe. Like him, we also are in danger of sinning, unless our Faith have a certain expansiveness, which makes us see everything with the eye of Faith, and gives our Faith that progress which God recompenses with a superabundance of light and joy. Yes, having once become members of the Church, it is our duty to look upon all things from a supernatural point of view. There is no danger of going too far, for we have the teachings of an infallible authority to guide us. “The just man liveth by Faith” (Romans 1:17). Faith is his daily bread. His mere natural life becomes transformed for good and all, if only he be faithful to his Baptism. Could we suppose that the Church, after all her instructions to her neophytes, and after all those sacred rites of their Baptism which are so expressive of the supernatural life, would be satisfied to see them straightway adopt that dangerous system which drives Faith into a nook of the heart and understanding and conduct, leaving all the rest to natural principles or instinct? No, it could not be so! Let us therefore imitate St. Thomas in his confession, and acknowledge that hitherto our Faith has not been perfect. Let us go to our Jesus, and say to him: “Thou art my Lord and my God! But alas! I have many times thought and acted as though thou wert my Lord and my God in some things, and not in others. Henceforth I will believe without seeing; for I would be of the number of those whom thou callest blessed!” The first Sunday after Easeter, commonly called with us Low Sunday, has two names assigned to it in the Liturgy: Quasimodo, from the first word of the Introit; and Sunday in albis (or, more explicitly, in albis depositis) , because on this day the neophytes assisted at the Church services attired in their ordinary dress. In the Middle-Ages it was called Close-Pasch, no doubt in allusion to its being the last day of the Easter Octave. Such is the solemnity of this Sunday that not only is it of Greater Double rite, but no feast, however great, can ever be kept upon it. At Rome, the Station is in the basilica of St. Pancras, on the Aurelian Way. Ancient writers have not mentioned the reason of this Church being chosen for today’s assembly of the faithful. It may, perhaps, have been on account of the saint’s being only fourteen years old when put to death: a circumstance which gave the young martyr a sort of right to have the neophytes round him, now that they were returning to their everyday life. Article 11 : THOUGHTS FOR "GOOD SHEPHERD" WEEK

"Final Thoughts on Sheep!" In Paschal time, we have Good Shepherd Sunday, because, in the Mass, there is read the Gospel of St. John, wherein our Lord calls Himself by this name. How very appropriate is this passage of the Gospel to this present Easter Season, when our Divine Master began His work of establishing and consolidating the Church, by giving it the Pastor, or Shepherd, who was to govern it to the end of time!