| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE LINK YOU WISH TO VIEW

| St. Patrick Apostle of Ireland | How the Catholic Faith Came to Ireland | Irish Catholics Come to America |

| St. Patrick Apostle of Ireland | How the Catholic Faith Came to Ireland | Irish Catholics Come to America |

IRISH CATHOLICS IN AMERICA

Part 1

Why Did They Come?

Part 1

Why Did They Come?

|

The Enormous Irish Ancestry in the USA

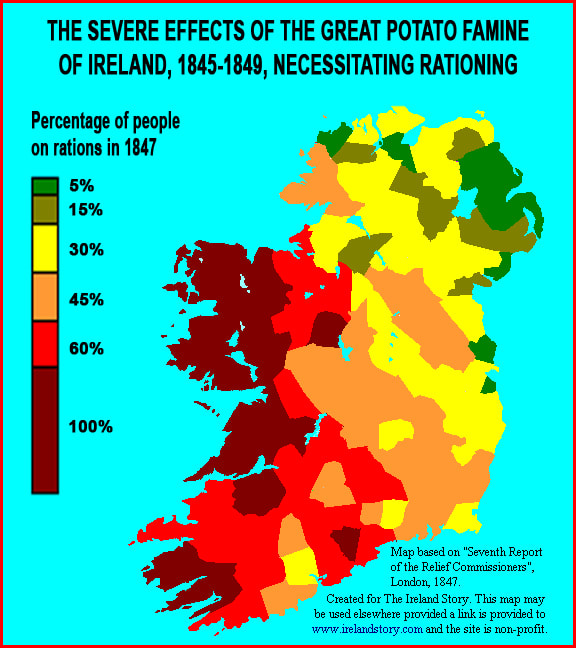

In 2002, more than 34 million Americans considered themselves to be of Irish ancestry, making Irish Americans the country's second-largest ethnic group. How did this come about? Why did the Irish come in great numbers to America? When did they first come? First Wave of Immigrants from Ireland The Irish first came to America in the 1600s with 50,000 to 100,000 people during the century and 100,000 more in the 1700s. Around 9 out of 10 of the Irish came as indentured servants. In colonial times, the Irish population in America was second in number only to the English. Many early Irish immigrants were of sturdy, Scotch-Irish stock. Most Scotch-Irish immigrants were educated, skilled workers. When they arrived in America most Irish-Americans lived in the large cities, such as Boston and New York, as well as Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, Missouri and San Francisco. During the American Revolution, the Irish made up about half of the Continental Army and signed the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Andrew Jackson was the first president to have Irish descendants. Second Major Wave of Immigrants from Ireland In the 19th century, many more Irish moved to America, most of them settling in the Northeast and the Midwest. They lived in small, tight communities in cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. From the 1820s to 1860, almost 2 million Irishmen came to America, 75% of them after the potato famine in 1847. The so-called “Irish Potato Famine” represented the first major influx of Irish immigration into America. Although the Irish potato blight receded in 1850, the effects of the famine continued to spur Irish emigration into the 20th century. Still facing poverty and disease, the Irish set out for America where they reunited with relatives who had fled at the height of the famine. However many Irish died on route to America from poverty, ill health and poor conditions after the great famine. Between 1845 and 1850, a devastating fungus destroyed Ireland's potato crop. During these years, starvation and related diseases claimed as many as a million lives, while perhaps twice that number of Irish immigrated — 500,000 of them to the United States, where they accounted for more than half of all immigrants in the 1840s. Between 1820 and 1975, over 4 million Irish settled in America. After 1860, another 2 million Irish came by 1900. In 1910, there were more people in New York City of Irish heritage than Dublin’s entire population. In the middle of that nineteenth century, more than one-half of the Ireland population emigrated to America. In 2002, more than 34 million Americans considered themselves to be of Irish ancestry, making Irish Americans the country's second-largest ethnic group. The famine did not affect all of Ireland in the same way. Suffering was most pronounced in western Ireland, particularly Connaught, and in the west of Munster. Leinster and especially Ulster escaped more lightly. The following map shows the severity of the famine across Ireland in 1847; the height of the Famine.

|

The Potato Famine in More Detail

The “Great Famine”, also called “Irish Potato Famine”, or the “Great Irish Famine”, or “Famine of 1845-1849”, was a famine that occurred in Ireland during the years 1845 to 1849, when the potato crop failed in successive years. The crop failures were caused by late blight, a disease that destroys both the leaves and the edible roots, or tubers, of the potato plant. The causative agent of late blight is the water mold Phytophthora infestans. The Irish famine was the worst to occur in Europe in the 19th century. In the early 19th century, Ireland’s tenant farmers, as a class, especially in the west of Ireland, struggled both to provide for themselves and to supply the British market with cereal crops. Many farmers had long existed at virtually the subsistence level, given the small size of their allotments and the various hardships that the land presented for farming in some regions. The potato, which had become a staple crop in Ireland by the 18th century, was appealing in that it was a hardy, nutritious, and calorie-dense crop and relatively easy to grow in the Irish soil. By the early 1840s almost half the Irish population—but primarily the rural poor—had come to depend almost exclusively on the potato for their diet. The rest of the population also consumed it in large quantities. A heavy reliance on just one or two high-yielding types of potato greatly reduced the genetic variety that ordinarily prevents the decimation of an entire crop by disease, and thus the Irish became vulnerable to famine. In September 1845 a strange disease struck the potatoes as they grew in fields across Ireland. Many of the potatoes were found to have gone black and rotten and their leaves had withered. In the harvest of 1845, between one-third and half of the potato crop was destroyed by the strange disease, which became known as 'potato blight'. It was not possible to eat the blighted potatoes, and the rest of 1845 was a period of hardship, although not starvation, for those who depended on it. The price of potatoes more than doubled over the winter: a hundredweight [112 pounds] of potatoes doubled in price. It is now known that the same potato blight struck in the USA in 1843 and 1844 and in Canada in 1844. It is thought that the disease travelled to from North America to Europe on trade ships and spread to England and finally to Ireland, striking the south-east of Ireland first. That partial crop failure, during 1845, was followed by more devastating failures from 1846 to 1849, as each year’s potato crop was almost completely ruined by the blight. The pictures below show what a blighted potato looks like. They have a soggy consistency and smell badly. Note that these pictures were taken recently, showing that potato blight still attacks sometimes today. The following spring, people planted even more potatoes. The farmers thought that the blight was a one-off and that they would not have to suffer the same hardship in the next winter. However, by the time harvest had come in Autumn (Fall) 1846, almost the entire crop had been wiped out. A Priest in Galway wrote "As to the potatoes they are all gone -- clean gone. If travelling by night, you would know when a potato field was near by the smell. The fields present a space of withered black stalks."

The English Prime-Minister of the day, Sir Robert Peel, set up a commission of enquiry to try to find out what was causing the potato failures and to suggest ways of preserving good potatoes. The commission was headed by two English scientists, John Lindley and Lyon Playfair. The farmers had already found that blight thrived in damp weather, and the commission concluded that it was being caused by a form of wet rot. The scientists were unable, however, to find anything with which to stop the spread of the blight. It was in 1846 that the first starvations started to happen. In 1847, the harvest improved somewhat and the potato crop was partially successful. However, there was a relapse in 1848 and 1849 causing a second period of famine. In this period, disease was spreading which, in the end, killed more people than starvation did. The worst period of disease was 1849 when Cholera struck. Those worst affected were the very young and very old. In 1850 the harvest was better and after that the blight never struck on the same scale again. |

Inadequate Governmental Relief

The English Prime-Minister of the day, Sir Robert Peel, set up a commission of enquiry to try to find out what was causing the potato failures and to suggest ways of preserving good potatoes. The commission was headed by two English scientists, John Lindley and Lyon Playfair. The farmers had already found that blight thrived in damp weather, and the commission concluded that it was being caused by a form of wet rot. The scientists were unable, however, to find anything with which to stop the spread of the blight. It was in 1846 that the first starvations started to happen.

The British government’s efforts to relieve the famine were inadequate. Although Conservative Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, continued to allow the export of grain from Ireland to Great Britain, he did what he could to provide relief in 1845 and early 1846. He authorized the import of corn (maize) from the United States, which helped avert some starvation. The Liberal (Whig) cabinet of Lord John Russell, which assumed power in June 1846, maintained Peel’s policy regarding grain exports from Ireland but otherwise took a laissez-faire approach to the plight of the Irish and shifted the emphasis of relief efforts to a reliance on Irish resources.

Much of the financial burden of providing for the starving Irish peasantry was thrown upon the Irish landowners themselves (through local poor relief) and British absentee landowners. Because the peasantry was unable to pay its rents, however, the landlords soon ran out of funds with which to support them, and the result was that hundreds of thousands of Irish tenant farmers and laborers were evicted during the years of the crisis. Under the terms of the harsh 1834 British Poor Law, enacted in 1838 in Ireland, the “able-bodied” indigent were sent to workhouses rather than being given famine relief per se. British assistance was limited to loans, helping to fund soup kitchens, and providing employment on road building and other public works. The Irish disliked the imported cornmeal, and reliance on it led to nutritional deficiencies.

Despite those shortcomings, by August 1847 as many as three million people were receiving rations at soup kitchens. All in all, the British government spent about £8 million on relief, and some private relief funds were raised as well. The impoverished Irish peasantry, lacking the money to purchase the foods their farms produced, continued throughout the famine to export grain, meat, and other high-quality foods to Britain. The government’s grudging and ineffective measures to relieve the famine’s distress intensified the resentment of British rule among the Irish people. Similarly damaging was the attitude among many British intellectuals that the crisis was a predictable and not-unwelcome corrective to high birth rates in the preceding decades and perceived flaws, in their opinion, in the Irish national character.

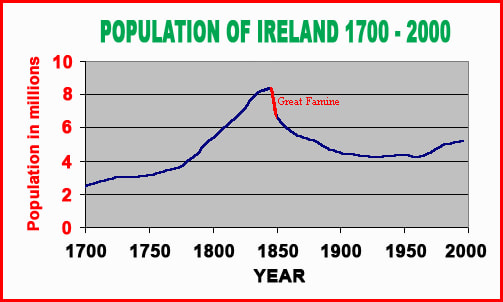

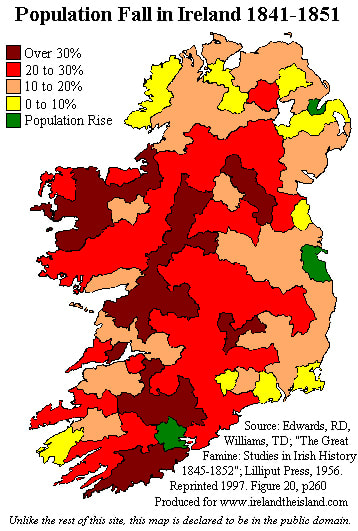

The famine proved to be a watershed in the demographic history of Ireland. As a direct consequence of the famine, Ireland’s population of almost 8.4 million in 1844 had fallen to 6.6 million by 1851. The number of agricultural laborers and smallholders in the western and southwestern counties underwent an especially drastic decline. A further aftereffect of the famine was thus the clearing of many smallholders from the land and the concentration of landownership in fewer hands. Thereafter, more land than before was used for grazing sheep and cattle, providing animal foods for export to Britain.

The precise number of people who died is perhaps the most keenly studied aspect of the famine: unfortunately, this is often for political rather than historical reasons. The only hard data that has survived is the 1841 and 1851 censuses, but the accuracy of these has been questioned. The reason for this is that the censuses recorded deaths by asking how many family members died in the past 10 years, but after the famine whole families had often left Ireland thus leaving many deaths unreported. It was argued by Edwards et al. that the precise number of deaths is of secondary concern to simple fact that a very many people died. Suffice it to say that estimates of deaths in the famine years range from 290,000 to 1,500,000 with the true figure probably lying somewhere around 1,000,000, or 12% of the population. We shall probably never know exactly how many lost their lives. It was undoubtedly the greatest period of death in Irish history, but its long term effects were to involve even more people than this.

People died from starvation or from typhus and other famine-related diseases. More people were killed by malnutrition-related diseases (such as dysentery and scurvy) as well as cholera that swept through the famine-ravaged countryside, than by actual starvation. While already prevalent in the west, many of these diseases spreads most effectively in damp conditions where people live closely together. Dysentery is not caused by hunger, and its incidence was not significantly higher during the famine as before. However, recovery from dysentery depends upon good nutrition and in many cases this was unavailable. The cholera epidemic was coincidental to the famine, but was responsible for a large number of deaths. It was the closely packed west that suffered most from these effects.

In the years after the famine, scientists discovered that the blight was, in fact, caused by a fungus, and they managed to isolate it. They named it Phytophthora Infestans. However it was not until 1882, almost 40 years after the famine, that scientists discovered a cure for Phytophthora Infestans: a solution of copper sulphate sprayed before the fungus had gained root. At the time of the famine there was nothing that farmers could do to save their crop.

The English Prime-Minister of the day, Sir Robert Peel, set up a commission of enquiry to try to find out what was causing the potato failures and to suggest ways of preserving good potatoes. The commission was headed by two English scientists, John Lindley and Lyon Playfair. The farmers had already found that blight thrived in damp weather, and the commission concluded that it was being caused by a form of wet rot. The scientists were unable, however, to find anything with which to stop the spread of the blight. It was in 1846 that the first starvations started to happen.

The British government’s efforts to relieve the famine were inadequate. Although Conservative Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, continued to allow the export of grain from Ireland to Great Britain, he did what he could to provide relief in 1845 and early 1846. He authorized the import of corn (maize) from the United States, which helped avert some starvation. The Liberal (Whig) cabinet of Lord John Russell, which assumed power in June 1846, maintained Peel’s policy regarding grain exports from Ireland but otherwise took a laissez-faire approach to the plight of the Irish and shifted the emphasis of relief efforts to a reliance on Irish resources.

Much of the financial burden of providing for the starving Irish peasantry was thrown upon the Irish landowners themselves (through local poor relief) and British absentee landowners. Because the peasantry was unable to pay its rents, however, the landlords soon ran out of funds with which to support them, and the result was that hundreds of thousands of Irish tenant farmers and laborers were evicted during the years of the crisis. Under the terms of the harsh 1834 British Poor Law, enacted in 1838 in Ireland, the “able-bodied” indigent were sent to workhouses rather than being given famine relief per se. British assistance was limited to loans, helping to fund soup kitchens, and providing employment on road building and other public works. The Irish disliked the imported cornmeal, and reliance on it led to nutritional deficiencies.

Despite those shortcomings, by August 1847 as many as three million people were receiving rations at soup kitchens. All in all, the British government spent about £8 million on relief, and some private relief funds were raised as well. The impoverished Irish peasantry, lacking the money to purchase the foods their farms produced, continued throughout the famine to export grain, meat, and other high-quality foods to Britain. The government’s grudging and ineffective measures to relieve the famine’s distress intensified the resentment of British rule among the Irish people. Similarly damaging was the attitude among many British intellectuals that the crisis was a predictable and not-unwelcome corrective to high birth rates in the preceding decades and perceived flaws, in their opinion, in the Irish national character.

The famine proved to be a watershed in the demographic history of Ireland. As a direct consequence of the famine, Ireland’s population of almost 8.4 million in 1844 had fallen to 6.6 million by 1851. The number of agricultural laborers and smallholders in the western and southwestern counties underwent an especially drastic decline. A further aftereffect of the famine was thus the clearing of many smallholders from the land and the concentration of landownership in fewer hands. Thereafter, more land than before was used for grazing sheep and cattle, providing animal foods for export to Britain.

The precise number of people who died is perhaps the most keenly studied aspect of the famine: unfortunately, this is often for political rather than historical reasons. The only hard data that has survived is the 1841 and 1851 censuses, but the accuracy of these has been questioned. The reason for this is that the censuses recorded deaths by asking how many family members died in the past 10 years, but after the famine whole families had often left Ireland thus leaving many deaths unreported. It was argued by Edwards et al. that the precise number of deaths is of secondary concern to simple fact that a very many people died. Suffice it to say that estimates of deaths in the famine years range from 290,000 to 1,500,000 with the true figure probably lying somewhere around 1,000,000, or 12% of the population. We shall probably never know exactly how many lost their lives. It was undoubtedly the greatest period of death in Irish history, but its long term effects were to involve even more people than this.

People died from starvation or from typhus and other famine-related diseases. More people were killed by malnutrition-related diseases (such as dysentery and scurvy) as well as cholera that swept through the famine-ravaged countryside, than by actual starvation. While already prevalent in the west, many of these diseases spreads most effectively in damp conditions where people live closely together. Dysentery is not caused by hunger, and its incidence was not significantly higher during the famine as before. However, recovery from dysentery depends upon good nutrition and in many cases this was unavailable. The cholera epidemic was coincidental to the famine, but was responsible for a large number of deaths. It was the closely packed west that suffered most from these effects.

In the years after the famine, scientists discovered that the blight was, in fact, caused by a fungus, and they managed to isolate it. They named it Phytophthora Infestans. However it was not until 1882, almost 40 years after the famine, that scientists discovered a cure for Phytophthora Infestans: a solution of copper sulphate sprayed before the fungus had gained root. At the time of the famine there was nothing that farmers could do to save their crop.

IRISH CATHOLICS IN AMERICA

Part 2

Where Did They Go?

Part 2

Where Did They Go?

|

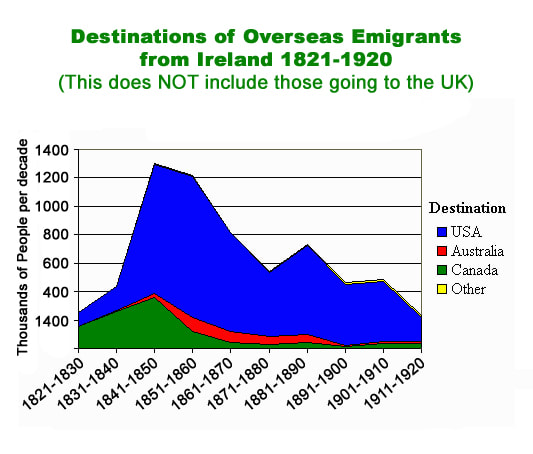

How Many Left Ireland?

There are no reliable population figures for Ireland before 1841, however estimates have been carried as far back as 1700. These figures show that Ireland's population rose slowly, from around 3 million in 1700, until the last half of the 18th century, when it had reached 4 million. It then entered a rapid period of increase (around 1.6% per year) which appears to have slowed to 0.6% by 1830. By 1841, the population had reached 8.2 million (according to the census, but the actual figure may be nearer 8.5 million compared to the current 2018 population of only 4.7 million). The population would probably have levelled off at a value of 9 million had it not been for the famine that began in 1845. The number of Irish who emigrated during the famine may have reached two million. Ireland’s population continued to decline in the following decades because of overseas emigration and lower birth rates. By the time Ireland achieved independence in 1921, its population was barely half of what it had been in the early 1840s. Emigration has been a feature of Irish history more than almost any other country in the world. This is shown by the fact that, apart from the 5 million people in Ireland, there are an estimated 55 million people worldwide who can trace their ancestry back to Ireland. Although the most awesome levels of emigration were to occur during and immediately after the famine, it would be a mistake to think that emigration began in 1845. In fact, there had been mass emigration from Ireland long before the famine. In this period, the Irish accounted for a third of all voluntary traffic across the Atlantic. These emigrants were mainly from Ulster and Leinster, with fewer coming from the poorer areas of Connaught and Munster. Between 1815 and 1845, 1.5 million Irish emigrated, mainly to Britain (around half-a-million) and to North America (around 1 million). Of those who went to North America, the majority settled in Canada. Between 1825 and 1830, records show that 128,200 Irish emigrated to north America, 61% of which went to Canada and 39% to the USA. In the decade 1831 to 1840, records show that 437,800 Irish emigrated (almost double the number of the previous decade). Of these, 60% went to Canada and 39% to the USA. The remaining 1% went to Australia. (Note that these figures are for emigration outside the UK only. They do not include emigrations to Britain.) Irish emigration to Australia was to rise over the next 40 years, reaching a peak of 11% of all emigration in the 1870s. Emigration to Canada was to fall sharply after the famine and soon the USA would be the dominant destination. This was all in the future, however. The Great Famine was to happen first. Adaptation and Assimilation The Irish immigrants left a rural lifestyle in a nation lacking modern industry. Many immigrants found themselves unprepared for the industrialized, urban centers in the United States. Though these immigrants were not the poorest people in Ireland (the poorest were unable to raise the required sum for steerage passage on a ship to America), by American standards, they were destitute. They often had no money beyond the fare for their passage, and, thus, settled in the ports of their debarkation. In time, the sum total of Irish-Americans exceeded the entire population of Ireland. New York City boasted more Irishmen than Dublin, Ireland! |

The Irish established patterns that newcomers to the United States continue to follow today. Housing choices, occupations entered, financial support to families remaining in the homeland, and chain immigrations which brought additional relatives to America, are some of these patterns.

Irish immigrants often crowded into subdivided homes that were intended for single families, living in tiny, cramped spaces. Cellars, attics and make-do spaces in alleys became home. Not only were many immigrants unable to afford better housing, but the mud huts in which many had lived in Ireland had lowered their expectations.

A lack of adequate sewage and running water in these places made cleanliness next to impossible. Disease of all kinds (including cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, and mental illness) resulted from these miserable living conditions. Thus, when the Irish families moved into neighborhoods, other families often moved out fearing the real or imagined dangers of disease, fire hazards, unsanitary conditions and the social problems of violence, alcoholism and crime.

Joining the Workforce

Irish immigrants often entered the workforce at the bottom of the occupational ladder and took on the menial and dangerous jobs that were often avoided by other workers. Many Irish women became servants or domestic workers, while many Irish men labored in coal mines and built railroads and canals. Railroad construction was so dangerous that it was said, “[there was] an Irishman buried under every tie.”

As Irish immigrants moved inland from eastern cities, they found themselves in heated competition for jobs. The audio recording, Immigrant Laborers in the Early 20th Century, describes how West Virginia coal operators fired union laborers and gave the jobs to Irish, Italian and African-American workers because, “[the] coal company owned them.” This competition heightened class tensions and, at the turn of the century, Irish Americans were often antagonized by organizations such as the American Protective Association (APA) and the Ku Klux Klan.

The Irish often suffered blatant or subtle job discrimination. Furthermore, some businesses took advantage of Irish immigrants’ willingness to work at unskilled jobs for low pay. Employers were known to replace (or threaten to replace) uncooperative workers and those demanding higher wages with Irish laborers.

Over time, many Irish climbed occupational and social ladders through politically appointed positions such as policeman, fireman, and teacher. Second and third generation Irish were better educated, wealthier, and more successful than were their parents and grandparents, as illustrated by the Kennedy family. The first Kennedy who arrived in the United States in 1848 was a laborer. His son had modest success in this country, but his grandson, college educated Joseph P. Kennedy, made the fortune that enabled the great grandsons (one of whom became President John F. Kennedy) to achieve great political success.

Religious Conflict and Discrimination

Ill will toward Irish immigrants because of their poor living conditions, and their willingness to work for low wages was often exacerbated by religious conflict. Centuries of tension between Protestants and Catholics found their way into United States cities and verbal attacks often led to mob violence. For example, Protestants burned down St. Mary’s Catholic Church in New York City in 1831, while in 1844, riots in Philadelphia left thirteen dead.

Anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments in the 1840s produced groups such as the nativist American Party, which fought foreign influences and promoted “traditional American ideals.” American Party members earned the nickname, “Know-Nothings,” because their standard reply to questions about their procedures and activities was, “I know nothing about it.”

In the Questions for Admittance to the American Party (1854), inductees committed to “…elect to all offices of Honor, Profit, or Trust, no one but native born citizens of America, of this Country to the exclusion of all Foreigners, and to all Roman Catholics, whether they be of native or Foreign Birth, regardless of all party predilections whatever.” This commitment helped elect American Party governors in Massachusetts and Delaware and placed Millard Fillmore on a presidential ticket in 1856.

Racial Tensions

During much of the nineteenth century, when large numbers of Irish and Blacks were present, they were pushed into competition. There are striking parallels in the culture and history of the two groups. They began their life in America with low social and economic status. Over time, they advanced in common fields such as sports, entertainment, religion, writing and publishing, and politics. They even had similar social pathologies—alcoholism, violence and broken homes. Rather than being united by their common hard life, they were divided by the need to compete. For political benefit, this pattern was reinforced as Blacks were drawn to the Republican Party while the Irish strength in numbers was wooed by the Democratic Party.

Both the Irish and Blacks had reason to feel they were treated unfairly in the workforce, and often at one another's expense. In the antebellum South, for instance, where slaveholders viewed slaves as valuable property, Blacks were prohibited from participating in hazardous, life-threatening work. Thus, many of the most dangerous jobs were left to the Irish who did not have such protection (or limitation). Thousands of Irish lives were lost in the building of the nation's canal and railroad systems.

The Conscription Act of 1863 exacerbated tense relationships. This act made all white men between the ages of twenty and forty-five years eligible for the draft by the Union Army. Free black men were permitted to “volunteer” to fight in the Civil War through the provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation. However, Blacks were not drafted or otherwise forced to fight. In addition, white men with money could illegally bribe doctors for medical exemptions, legally hire a substitute, or pay for a commutation of a draft. Lower-class workers could not afford to pay for deferments. The inequities in draft eligibility between blacks, monied whites, and lower-class whites (many of whom were Irish), inevitably increased racial tensions.

Several cities suffered draft riots in which enrollment officers and free blacks were targeted for violence. The largest such incident began on June 11th, 1863, in New York City when more than 100 people were murdered by an angry mob.

Irish immigrants often crowded into subdivided homes that were intended for single families, living in tiny, cramped spaces. Cellars, attics and make-do spaces in alleys became home. Not only were many immigrants unable to afford better housing, but the mud huts in which many had lived in Ireland had lowered their expectations.

A lack of adequate sewage and running water in these places made cleanliness next to impossible. Disease of all kinds (including cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, and mental illness) resulted from these miserable living conditions. Thus, when the Irish families moved into neighborhoods, other families often moved out fearing the real or imagined dangers of disease, fire hazards, unsanitary conditions and the social problems of violence, alcoholism and crime.

Joining the Workforce

Irish immigrants often entered the workforce at the bottom of the occupational ladder and took on the menial and dangerous jobs that were often avoided by other workers. Many Irish women became servants or domestic workers, while many Irish men labored in coal mines and built railroads and canals. Railroad construction was so dangerous that it was said, “[there was] an Irishman buried under every tie.”

As Irish immigrants moved inland from eastern cities, they found themselves in heated competition for jobs. The audio recording, Immigrant Laborers in the Early 20th Century, describes how West Virginia coal operators fired union laborers and gave the jobs to Irish, Italian and African-American workers because, “[the] coal company owned them.” This competition heightened class tensions and, at the turn of the century, Irish Americans were often antagonized by organizations such as the American Protective Association (APA) and the Ku Klux Klan.

The Irish often suffered blatant or subtle job discrimination. Furthermore, some businesses took advantage of Irish immigrants’ willingness to work at unskilled jobs for low pay. Employers were known to replace (or threaten to replace) uncooperative workers and those demanding higher wages with Irish laborers.

Over time, many Irish climbed occupational and social ladders through politically appointed positions such as policeman, fireman, and teacher. Second and third generation Irish were better educated, wealthier, and more successful than were their parents and grandparents, as illustrated by the Kennedy family. The first Kennedy who arrived in the United States in 1848 was a laborer. His son had modest success in this country, but his grandson, college educated Joseph P. Kennedy, made the fortune that enabled the great grandsons (one of whom became President John F. Kennedy) to achieve great political success.

Religious Conflict and Discrimination

Ill will toward Irish immigrants because of their poor living conditions, and their willingness to work for low wages was often exacerbated by religious conflict. Centuries of tension between Protestants and Catholics found their way into United States cities and verbal attacks often led to mob violence. For example, Protestants burned down St. Mary’s Catholic Church in New York City in 1831, while in 1844, riots in Philadelphia left thirteen dead.

Anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments in the 1840s produced groups such as the nativist American Party, which fought foreign influences and promoted “traditional American ideals.” American Party members earned the nickname, “Know-Nothings,” because their standard reply to questions about their procedures and activities was, “I know nothing about it.”

In the Questions for Admittance to the American Party (1854), inductees committed to “…elect to all offices of Honor, Profit, or Trust, no one but native born citizens of America, of this Country to the exclusion of all Foreigners, and to all Roman Catholics, whether they be of native or Foreign Birth, regardless of all party predilections whatever.” This commitment helped elect American Party governors in Massachusetts and Delaware and placed Millard Fillmore on a presidential ticket in 1856.

Racial Tensions

During much of the nineteenth century, when large numbers of Irish and Blacks were present, they were pushed into competition. There are striking parallels in the culture and history of the two groups. They began their life in America with low social and economic status. Over time, they advanced in common fields such as sports, entertainment, religion, writing and publishing, and politics. They even had similar social pathologies—alcoholism, violence and broken homes. Rather than being united by their common hard life, they were divided by the need to compete. For political benefit, this pattern was reinforced as Blacks were drawn to the Republican Party while the Irish strength in numbers was wooed by the Democratic Party.

Both the Irish and Blacks had reason to feel they were treated unfairly in the workforce, and often at one another's expense. In the antebellum South, for instance, where slaveholders viewed slaves as valuable property, Blacks were prohibited from participating in hazardous, life-threatening work. Thus, many of the most dangerous jobs were left to the Irish who did not have such protection (or limitation). Thousands of Irish lives were lost in the building of the nation's canal and railroad systems.

The Conscription Act of 1863 exacerbated tense relationships. This act made all white men between the ages of twenty and forty-five years eligible for the draft by the Union Army. Free black men were permitted to “volunteer” to fight in the Civil War through the provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation. However, Blacks were not drafted or otherwise forced to fight. In addition, white men with money could illegally bribe doctors for medical exemptions, legally hire a substitute, or pay for a commutation of a draft. Lower-class workers could not afford to pay for deferments. The inequities in draft eligibility between blacks, monied whites, and lower-class whites (many of whom were Irish), inevitably increased racial tensions.

Several cities suffered draft riots in which enrollment officers and free blacks were targeted for violence. The largest such incident began on June 11th, 1863, in New York City when more than 100 people were murdered by an angry mob.

Web Hosting by Just Host