| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

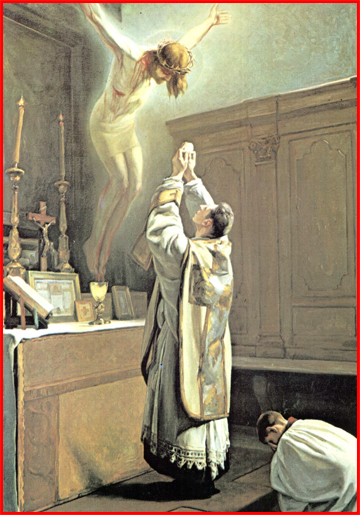

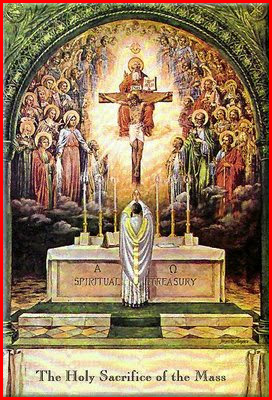

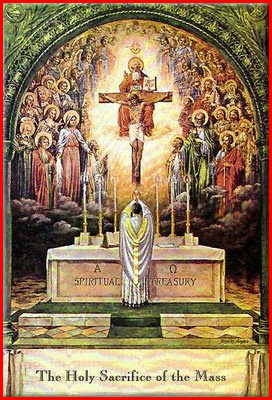

A LONG SERIES OF REGULARLY ADDED ARTICLES EXPLAINING

The History of Mass ... The Types or Forerunners of the Mass ... The Prayers of the Mass ...

The Symbolism Behind the Mass ... The Objects Used at Mass ... The Purpose of the Mass ...

The Power of the Mass ... The Variations of Mass ... Our Need of the Mass

The History of Mass ... The Types or Forerunners of the Mass ... The Prayers of the Mass ...

The Symbolism Behind the Mass ... The Objects Used at Mass ... The Purpose of the Mass ...

The Power of the Mass ... The Variations of Mass ... Our Need of the Mass

“The Mass is very long and tiresome, unless one loves God” (G.K. Chesterton).

“It would be easier for the world to survive without the sun, than to do without Holy Mass!” (St. Padre Pio of Pietrelcina).

“She [the Holy Mother] said if only one priest could offer the bloodless Sacrifice as worthily and with the same disposition as the Apostles, he could avert all the disasters [that are to come]” (Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich).

“Mass badly celebrated is an enormous evil. Ah! It is not a matter of indifference how it is said! ... I have had a great vision on the mystery of Holy Mass and I have seen that whatever good has existed since creation, is owing to it”

(Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich).

“It would be easier for the world to survive without the sun, than to do without Holy Mass!” (St. Padre Pio of Pietrelcina).

“She [the Holy Mother] said if only one priest could offer the bloodless Sacrifice as worthily and with the same disposition as the Apostles, he could avert all the disasters [that are to come]” (Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich).

“Mass badly celebrated is an enormous evil. Ah! It is not a matter of indifference how it is said! ... I have had a great vision on the mystery of Holy Mass and I have seen that whatever good has existed since creation, is owing to it”

(Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich).

THE LATEST ARTICLE WILL ALWAYS BE AT THE END OF THE PAGE

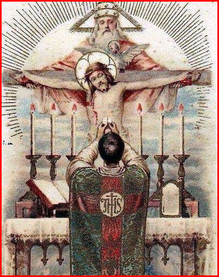

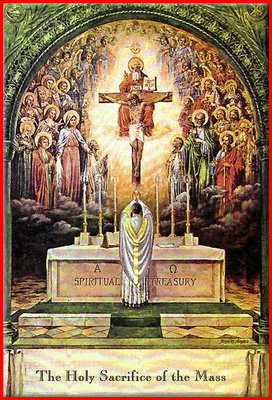

1. OUR GREATEST TREASURE—OUR GREATEST NEGLECT

1. OUR GREATEST TREASURE—OUR GREATEST NEGLECT

|

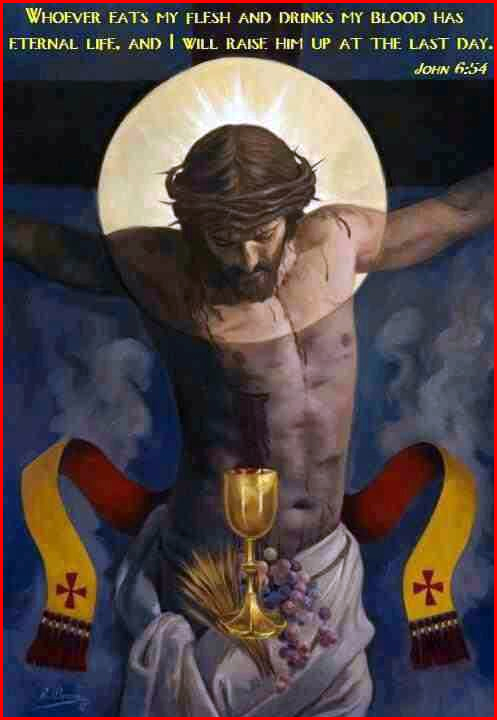

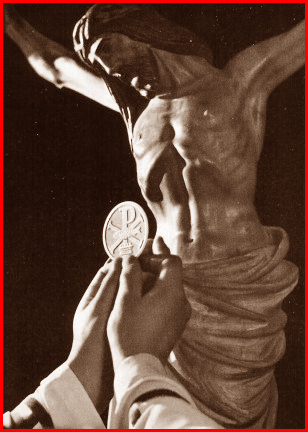

“If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10).

How many people understand what the Mass really is? Many persons no longer have a scruple about missing Sunday Mass. Today, an increasing number of people think you can be a ‘good’ Catholic without attending Mass! In fact, only a minority of baptized Catholics attend Mass. In the USA, regular Mass attendees are only 20% of the US Catholic population. In some other countries, it is even under 10%. Many attend Mass simply through force of habit, to conform to custom, for family and social reasons, or simply to avoid mortal sin. Our Greatest Treasure has become our greatest neglect! “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). If you truly knew what the Mass was, then you would live the Mass every day! And how many people live their Mass? No long or detailed observation of the faithful, who attend Sunday Mass, is required, to ascertain that the greater part of those present at Mass, are thinking of anything and everything else, except what is taking place at the altar. And how many—once they have left the church—ever give another thought to their morning Mass? Our Greatest Treasure has become our greatest neglect! If we would live the Mass, we must properly participate in it. “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). And in order to properly participate in the Mass, we must understand it. If certain Catholics attend Mass only to avoid serious sin—if they have no love for the Mass—it is because they do not understand it; do not take part in it; do not live it. The Mass for them constitutes an exterior act of religion unlinked with life, a “church service” to which they go with resignation and of which they remain the indifferent witnesses and passive spectators. Our Greatest Treasure has become our greatest neglect! “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). Toward the middle of the fifth century there lived in the City of Rome a hidden saint named Alexius. He was the son of the Roman senator Euphemian, a man of great wealth. At an early age he felt inspired by God to leave his home for a strange country. Obedient to this inner voice, he went forth from his father's house and passed seventeen years in pious pilgrimages in the East, amid many trials and dangers. At length, to show his love for God in a still more striking manner, he resolved to return to his house in the garb of a poor beggar and spend there the remainder of his days. On arriving at Rome, he met his father, Euphemian, in the street, followed by a train of attendants, as became his high rank. Clad in rags and attenuated by fasts, Alexius was not recognized by his father. So he besought him for charity to give him shelter in his house, and for food, the crumbs that fell from his table. The nobleman, moved with pity, bade one of his servants to lodge and take care of the poor beggar. The servant con-ducted him to an obscure apartment under the staircase, where for twenty-two years he passed a life of suffering and humiliation, because the menials made him a butt for their ridicule, beat him and subjected him to many indignities, which he bore with invincible patience. Thus did the life he spent in his father's house become one long-continued prayer, fast, penance and austerity. At length, when he felt death approaching, he begged one of the servants to bring him writing materials. Then he wrote down on a sheet of paper the story of his whole life, whither he had wandered, what had happened to him, what he had suffered at home and abroad. He stated at the same time that he was Alexius, the son of the house, whom his parents had missed for so many years. This paper he held in his hands until death took him on a Sunday at the time when his parents were at Mass. No sooner had his soul taken flight to Heaven than all the bells of the churches in Rome began to ring, and a loud voice was heard to say distinctly three times: “Go to the house of Euphemian to find the great friend of God who has just died and prays for Rome, and all he asks is granted” Then went the people to find the Saint, and Euphemian was the first to enter his house. He went straightway to the room under the staircase, and to his surprise found that the poor beggar had just expired. Seeing the paper, he took it out of his hands, and reading its contents aloud burst into tears and embraced his holy son, hardly able to utter a word. The mother of Alexius was still more deeply affected and cried out: “O my son, why have I known thee too late!” The story of Alexius is a good illustration of what often happens in these days to many a Christian. Alexius went back to his father's house as a beggar clad in tatters, the better to disguise his rank and wealth. Our dear Savior acts in the same manner in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. There He is, but by no outward sign does He betray His real presence; His heavenly glory and brightness He hides from us; He is there, as one may say, in a poor miserable dress, under the appearances of bread and wine. As the parents of Alexius paid little attention to their son in his state of poverty and subjection, so, in this life, many Christians pay but little attention to Jesus Christ, because He humbly condescends to conceal His glory in the Sacrament of His love. But when this life is over and they come to see Him face to face, whom here they possessed in the Holy Eucharist, at the sight of the consolations, of the beauty and of the riches that they failed to recognize in time, they will exclaim with the mother of Alexius: “O, Jesus! dear Saviour, why have we known Thee too late? Ah! Had we only known Thee in Thy mystery of love, when alive on earth, we would have allowed no opportunity to escape us of assisting at the celebration of Thy sacred mysteries, of receiving Thee in Holy Communion. Not an hour should have passed without a thought of Thee. Thou wouldst have been our whole delight, our whole joy, our whole happiness, the object of all our desires, thoughts and actions. O dear Lord, why have we known Thee too late!” “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). What then, is the Mass? First and foremost, the Mass is a Sacrifice. The Sacrifice of Christ and the Church. The Sacrifice of the Head and members of the Mystical Body of Christ. Should we seek to know what Christ’s Sacrifice really was, we would learn that our Divine Lord’s Sacrifice consisted not alone in his martyrdom of a few hours on the Cross; but in his whole life of renunciation and obedience, of which Calvary was the glorious culmination. This precise definition of Christ’s Sacrifice is, perhaps, one of the most important that His Holiness, Pope Pius XII, has given in regard to the Mass, in his encyclical Mediator Dei et hominum, paragraph 17: “Indeed, scarcely has `the Word been made flesh’ (John 1:14) than He manifests Himself to the world in His priestly character; by making an act of submission to God the Father, which is to be life-long. `Therefore, in coming into the world, He says, behold, I come to do Your will, O God’ (Hebrews 10: 5-7). This act is to be brought to its full perfection in a heroic manner in the bloody Sacrifice of the Cross: ‘It is in this “will” that we have been sanctified through the offering of the Body of Jesus Christ once for all’ (Hebrews 10:10). All Christ’s activity among men had no other purpose. "As a Child, He is presented to the Lord in the Temple of Jerusalem. As a Youth, He visits it anew. Later on, He will often return to instruct the people and to pray. Before inaugurating His public ministry, He fasts for forty days. By word and example, He exhorts us to pray, whether by day or by night. As Master of Truth, He `enlightens every man’, (John 1:9); that mortals may recognize the true immortal God, and not be `among those who draw back unto destruction, but of those who have Faith to the saving of the soul’, (Hebrews 1:39). As Shepherd, He has charge of His flock. He leads it into living pastures, and gives it a law to be observed: in order that none may turn aside from Him, nor from the route mapped out by him; but that all may lead holy lives under His inspiration and guidance. At the Last Supper He celebrated the New Passover with pomp and solemn rite; and, thanks to the divine institution of the Eucharist, assures its permanence. The next day, uplifted between Heaven and Earth, He offers His life in sacrifice for our salvation; and from His pierced side, causes the Sacraments to flow, which distribute to men’s souls the fruits of Redemption. In so doing, He has no other aim than His Father’s glory, and man’s greater sanctity” (Pope Pius XII, Encyclical Mediator Dei ). “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). St. Leonard of Port Maurice, in his excellent book, The Hidden Treasure of the Holy Mass, writes: “How horrible is the excessive ignorance of some Christians, who, not recognizing the immense preciousness of Holy Mass, come to treat it as a matter of vulgar purchase for filthy lucre. Thence, sometimes, the indecent language with which such persons will address a priest; as, for instance: ‘May I pay for a Mass this morning?’ Pay for Mass! And where will you find money for that? What is the equivalent for a Mass, when one unbloody sacrifice of Christ outweighs, in value, the whole of paradise itself? Such ignorance is intolerable! The trifle you give to the priest is a gift toward his daily support, is not in any sense the payment of so much purchase-money—for Holy Mass is a treasure without price!” (St. Leonard of Port Maurice). “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). “Whenever we stay away from Mass through neglect, especially on Sundays and holy-days of obligation, we thereby give to understand that we do not care to give glory to God and His saints, as little as we care to obtain the graces of God for ourselves and others by so powerful a means as that of the Mass. And do we imagine that this contempt of ours for God’s glory and His blessings will go unpunished? We cannot complain that the Almighty should treat us with similar neglect, if He bestows His choicest gifts upon others, and passes us by unnoticed. We made the choice and we must abide the issue!” (Fr. Michael Müller, C.SS.R., The Holy Mass). “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). St. Leonard of Port Maurice has some serious words to address to priests: “And for you, O priests, tremble before the justice of God if, either by excessive haste or irreverent negligence, you transgress the rules of the sacred ceremonies, if you hurry out your words, or confuse the different acts, and, in short, bustle slipshod through your Mass. Reflect that then you consecrate, you touch, you receive, the Son of the Most High; nor are you blameless in regard to each the very slightest ceremony which you either leave out, or perform more or less imperfectly. Such is the teaching of the most learned Suarez, when he treats of the question, ‘Vel unius caerimoniae omissio culpae reatum inducit’ (Vol. 5, part 3, disertation 85, lect. 2). “Whence St. John of Avila, was always firmly of opinion that the Eternal Judge will, in the case of priests, make, before everything else, a most rigorous scrutiny into all the Masses they have celebrated. Thus when on one occasion a young priest had departed to the other world, just as he had barely finished his first Mass, the holy man, hearing of his death, heaved a sigh, and asked: ‘Had he ever offered Mass?’ And when they told of his happy fate in dying so soon as his first Mass was celebrated, ‘Ah!’ he resumed, ‘He has much to thank God for, if he has once celebrated Mass!’ “But you and I, who have celebrated so many, how shall we pass before the tribunal of God? Let us, then, make the holy resolution to re-study (at latest in our first spiritual retreat) all the rubrics of the Missal, and all the sacred ceremonial, so as to celebrate for the future with all the exactness possible. It is my hope that if we priests shall generally celebrate with serious and devout exterior composure, and, what is far more, with thorough interior fervor of soul, the laity will return to daily hearing of Holy Mass, and to hearing it with deepest devotion. Thus we shall have the joy of beholding renewed in the Christians of our time all the fervor of the first believers of God's Church, and thus will our most gracious and Almighty God be supremely honored and glorified!” (St. Leonard of Port Maurice, The Hidden Treasure of the Holy Mass). “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). This is why, in some sacristies (today a rarity), you would see a sign posted on the sacristy wall—facing the priest as he vested for Holy Mass—saying: “O Priest of God! Say this Holy Mass as though it was the first Holy Mass of your life! O Priest of God! Say this Holy Mass as though it was the last Holy Mass of your life!” Familiarity breeds contempt! That is why we are contemptuous of the Holy Mass today—whereby we never or rarely genuflect to the Holy Eucharist in the church—or genuflect hastily, automatically, routinely, distractedly, etc. That is why we follow the prayers of the Holy Mass with the same sentiments— automatically, routinely, distractedly, etc. That is why we rarely or barely prepare ourselves for Holy Mass beforehand, nor give sufficient thanks afterwards. As Our Lord said: “Well did Isaias prophesy of you hypocrites, as it is written: ‘This people honoureth Me with their lips, but their heart is far from Me!’” (Mark 7:6). “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). These things would not be so, if we only had a true notion and appreciation of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass! It is because we do not really know the gift of God in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass that we are lukewarm, indifferent and nonchalant during our rare attendances at Mass. This lukewarm state about the Mass should terrify us—especially in view of God’s language on the matter, which states: “I know thy works—that thou art neither cold, nor hot! I would thou wert cold, or hot! But because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold, not hot, I will begin to vomit thee out of My Mouth!” (Apocalypse 3:15-16). Hence the reason behind this particular webpage—the Holy Mass Explained—so that we might “ekindle in our hearts the fire of love” towards the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. However, since we cannot love what we do not know, we need to seriously—not superficially or fleetingly—study the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass from all its many different aspects, in order to provide the ‘kindling wood’ for the fire of love. “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). After speaking of vomiting the lukewarm from His Mouth, God then says: “Thou sayest: ‘I am rich, and made wealthy, and have need of nothing!’ and knowest not, that thou art wretched, and miserable, and poor, and blind, and naked! I counsel thee to buy of Me gold, fire tried, that thou mayest be made rich; and mayest be clothed in white garments, and that the shame of thy nakedness may not appear; and anoint thy eyes with eye-salve, that thou mayest see. Such as I love, I rebuke and chastise. Be zealous therefore, and do penance! Behold, I stand at the gate, and knock! If any man shall hear My voice, and open to Me the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with Me. To him that shall overcome, I will give to sit with me in my throne!” (Apocalypse 3:17-21). This is what we shall do in these articles—buy from God “eye-salve” to anoint our blind eyes, that we might see the beauty and grandeur and power of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Then we shall beg the gold of charity from God, to be able to love the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass as it should be loved. Then our spiritual life and chance of salvation shall be ‘jump-started’! Then we may well have a chance of not being among the many that are lost, but among the few that are saved! “A certain man said to Jesus: ‘Lord! Are they few that are saved?’ But he said to them: ‘Strive to enter by the narrow gate; for many, I say to you, shall seek to enter, and shall not be able! But when the Master of the house shall be gone in, and shall shut the door, you shall begin to stand without, and knock at the door, saying: ‘Lord! Open to us!’ And He answering, shall say to you: ‘I know you not, whence you are!’ Then you shall begin to say: ‘We have eaten and drunk in Thy presence, and Thou hast taught in our streets!’ And He shall say to you: ‘I know you not, whence you are! Depart from Me, all ye workers of iniquity!” ’” (Luke 13:23-27). “If thou didst know the gift of God!” (John 4:10). |

Article 2

IS THE BREAD & WINE, MORE LIKE PEARLS BEFORE SWINE?

IS THE BREAD & WINE, MORE LIKE PEARLS BEFORE SWINE?

“Give not that which is holy to dogs; neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest perhaps they trample them under their feet, and turning upon you, they tear you!” (Matthew 7:6)

|

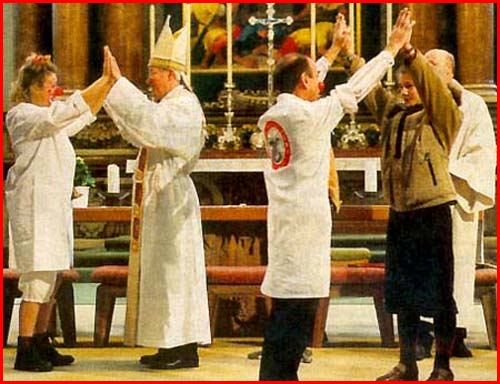

“Give not that which is holy to dogs!” (Matthew 7:6).

Shocking as though it sounds, this can well be true of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. But just look for a moment at those words--“Give not that which is holy to dogs!”—why not give what is holy to dogs? Because dogs cannot understand what holiness is, nor can they treat holy things holily. They are animals, not humans. Yet we are called “rational animals”—are we not? Now if cease thinking correctly—or more precisely, if we cease thinking holily—then the “rational” part of our nature and name is lacking, and, instead of being “rational animal”, we are left with the name “animal”—or rather, we become animalistic. Is this not what happens when a person sins? He acts more like an animal than a human being! Look at the case of abortion, or murder, or physical violence, or rape, or lust, or gluttony—in these cases a person acts more like an animal than a human being made in the image and likeness of God. Are There Any ‘Dogs’ In Your Church? Seen Any? Perhaps you have sometimes seen a dog stray into your church at some time. What does the dog do—or, rather, what doesn’t it do? The dog is oblivious to the location that it finds itself in—its attitude is not different to what it is outside on the street, or in the house of its owner. Everything is the same to the dog. The dog does not preen itself before coming in, nor does it wear anything special—it carries the same old dirty fur that it always does. Why? Because the dog does not think—it cannot think—it does not recognize nor distinguish a holy place from a common place. Therefore, with this canine attitude—like a “dumb dog”—it does genuflect or make a sign of the cross. It just trots in and goes and does wherever it wants, and does whatever it wants. If it feels like barking, it will bark; if it wants to sniff at things, it will sniff; if it wants to pee somewhere, it will pee. After all—it is mindless—and it acts in a church like it would act anywhere else—and act as though it's normal—which, for a “dumb dog”, it is normal. Heartless Hounds—Lippy Labradors Dogs can be taught many tricks, even tricks that resemble human behavior. You can teach a parrot the Hail Mary, you can train a dog to look as though it is praying. Will the parrot or dog become holy doing this? Will the parrot or dog grow in grace? Of course not, they are both mindless creatures merely mimicking human behavior. Yet is not the same true, to some degree, of human beings—who have descended to “animalistic” levels of action. How many persons mindlessly say hundreds of Hail Marys? How many persons—like a performing dog—go through their usual routine of ‘tricks’ during Mass? Kneel down—stand up—sit down—stand up—kneel down again—join your hands—say “Amen”—sit down again—go out for Communion—put out your tongue or hand—walk back to your place, etc. Visions of Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich This state of affairs was clearly shown to Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich, in a series of visions spanning many years, in which she was shown a time where zeal would be lost and counterfeit church must be built alongside the true Church that was being deliberately destroyed. Here are the pertinent extracts which she recounts in the following words: Vision of September 12th, 1820 “I saw a strange church being built against every rule … No angels were supervising the building operations. In that church, nothing came from high above…There was only division and chaos. It is probably a church of human creation, following the latest fashion, as well as the new heterodox Church of Rome [one world church of the False Prophet], which seems of the same kind…” “I saw again the strange big church that was being built there (in Rome). There was nothing holy in it. I saw this just as I saw a movement led by Ecclesiastics to which contributed angels, saints and other Christians. But there (in the strange big church) all the work was being done mechanically (i.e., according to set rules and formula). Everything was being done, according to human reason. I saw all sorts of people, things, doctrines, and opinions. There was something proud, presumptuous, and violent about it, and they seemed to be very successful. I did not see a single Angel nor a single saint helping in the work. But far away in the background, I saw the seat of a cruel people armed with spears, and I saw a laughing figure which said: ‘Do build it as solid as you can; we will put it to the ground’.” “I saw that many of the instruments in the new Church, such as spears and darts, were meant to be used against the living Church. Everyone dragged in something different: clubs, rods, pumps, cudgels, puppets, mirrors, trumpets, horns bellows – all sorts of things. In the cave below (the sacristy) some people kneaded bread, but nothing came of it; it would not rise. The men in the little mantles brought wood to the steps of the pulpit to make a fire. They puffed and blew and labored hard, but the fire would not burn. All they produced was smoke and fumes. Then they broke a hole in the roof and ran up a pipe, but the smoke would not rise, and the whole place became black and suffocating. Some blew the horns so violently that the tears streamed from their eyes. All in this church belonged to the earth, returned to the earth. All was dead, the work of human skill, a church of the latest style, a church of man’s invention like the new heterodox church in Rome.” Vision of September 27th, 1820 “I saw deplorable things: they were gambling, drinking, and talking in church. All sorts of abominations were perpetrated there. Priests allowed everything and said Mass with much irreverence. I saw that few of them were still godly, and only a few had sound views on things.” Vision of October 1st, 1820 “The Church is in great danger …The Protestant doctrine and that of the schismatic Greeks are to spread everywhere. I now see that in this place (Rome) the (Catholic) Church is being so cleverly undermined, that there hardly remain a hundred or so priests who have not been deceived. They all work for destruction, even the clergy. A great devastation is now near at hand … In those days Faith will fall very low and it will be preserved in some places only … Religion is there so skillfully undermined and stifled that there are scarcely 100 faithful priests ... Everyone, even ecclesiastics, are laboring to destroy (and) ruin is at hand. The enemies of the Church are firmly resolved to destroy the pious and learned men that stand in their way.” Vision of October 4th, 1820 “When I saw the Church of St Peter in ruins and the manner in which so many of the clergy were themselves busy at this work of destruction – none of them wishing to do it openly in front of the others – I was in such distress that I cried out to Jesus with all my might, imploring His mercy. He said that the Church would seem to be in complete decline. But she would rise again; even if there remained but one Catholic, the Church would conquer again because she does not rest on human counsels and intelligence. It was shown to me that there were almost no Christians left in the old acceptation of the word.” Vision of October 7th, 1820 “As I was going through Rome, I saw a great palace engulfed in flames from top to bottom ... The Church is completely isolated and as if completely deserted. It seems that everyone is running away. Everywhere I see great misery, hatred, treason, rancor, confusion and utter blindness. O city! O city! What is threatening thee? The storm is coming, do be watchful!…” Vision of June 1st, 1821 “Among the strangest things that I saw, were long processions of bishops. Their thoughts and utterances were made known to me through images issuing from their mouths. Their faults towards religion were shown by external deformities. A few had only a body, with a dark cloud of fog instead of a head. Others had only a head, their bodies and hearts were like thick vapors. Some were lame; others were paralytics; others were asleep or staggering. I saw what I believe to be nearly all the bishops of the world, but only a small number were perfectly sound … I saw a number of people looking quickly right and left, that is, in the direction of the world… Then I saw that everything pertaining to Protestantism was gradually gaining the upper hand, and the Catholic religion fell into complete decadence. Most priests contributed to the work of destruction. In those days, Faith will fall very low, and it will be preserved in some places only, in a few cottages and in a few families which God has protected from disasters and wars…” Vision of April 22nd, 1823 “I saw that many pastors allowed themselves to be taken up with ideas that were dangerous to the Church. They were building a great, strange, and extravagant Church. Everyone was to be admitted in it in order to be united and have equal rights: Evangelicals, Catholics sects of every description. Such was to be the new Church … They built a large, singular, extravagant church which was to embrace all creeds with equal rights: Evangelicals, Catholics, and all denominations, a true communion of the unholy with one shepherd and one flock. All was made ready, many things finished; but, in place of an altar, were only abomination and desolation. Such was the new church to be, and it was for it that he had set fire to the old one … I saw the fatal consequences of this counterfeit church: I saw it increase; I saw heretics of all kinds flocking to the city. I saw the ever-increasing tepidity of the clergy, the circle of darkness ever widening…” |

Article 3

THE HOLY MASS PREFIGURED IN THE OLD & NEW TESTAMENTS

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

THE HOLY MASS PREFIGURED IN THE OLD & NEW TESTAMENTS

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

“But Melchisedech the King of Salem, bringing forth bread and wine, for he was the priest of the most high God”

(Genesis 14:18)

(Genesis 14:18)

|

Advertised and Promised From the Beginning of Time!

When something ‘great’ comes onto the market, you can bet your “bottom dollar” that it will be heavily advertised in order to draw attention to the product and increase the likelihood of sales. God is not different. He could “keep under wraps” the great things that He was about unleash on to the world. The following persons and events of the Old Testament times prefigure or symbolize the two great Gifts that God intended to give to us from all eternity—namely, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the Holy Eucharist, which is born of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. There are a number of ways in which God has foreshadowed the Sacrifice of Christ on the Cross of Calvary and Christ’s Real Presence in the Holy Eucharist. He has done this through the various signs or “types” or “shadows” that would symbolize or prefigure the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and the Holy Eucharist. Types or Shadows of the Holy Sacrifice of Calvary and the Mass As regards the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass—which is essentially the same thing as the bloody slaughter of Christ in His Sacrifice on Calvary, but in an unbloody manner—we have the following chief types or symbols prefiguring the Sacrifice of Christ on the Cross of Calvary and the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. There are more, but covering more will take much more time. These alone will cover quite a few articles: (1) The slaughter of Abel by Cain (2) The Ark of Salvation of Noe (3) The Sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham on the Mountain (4) The Attempted Killing and Selling into Slavery of Joseph (5) The Paschal Lamb before the Exodus from Egypt (6) The Water spring miraculously from the Rock during the Exodus (7) The Fiery Presence of God upon Mt. Sinai during the Exodus (8) The Jewish Scapegoat (9) The Sacrifices of the Temple (10) The Design of the Temple in Relation to a Catholic Church (11) The Last Supper from a Sacrificial Viewpoint (12) The Sacrifice of Our Lord on the Cross on Mt. Calvary Types or Shadows of the Holy Eucharist As regards the Holy Eucharist—which is Our Spiritual nourishment by the Body and Blood of Our Lord Himself—we have many types or shadows that prefigure this incredibly great Sacrament. In addition to the chief types found in the Old Testament, we will add several from the New Testament, which cannot be ignored. (1) The Fruits of the Trees in Paradise and the Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil (2) The Sacrifice of Melchisedech of Bread and Wine (3) The Manna and Quail that fell in the desert for the Chosen People (4) The Bread of the Presence revealed to Moses (5) The Ark of the Covenant (6) The Roles of Bread, Wine and Blood in the Old Testament (7) The Eating of the Paschal Meal (8) The Prophet Elias fed with Bread by Ravens in the Desert (9) Our Lord’s Birth in Bethlehem—the “Town of Bread” (10) The Wedding Feast at Cana (11) The Miraculous Feeding of the Four and the Five Thousand by Jesus (12) Jesus claims to the Bread of Heaven (13) The Last Supper from a Sacramental Viewpoint |

Article 4

SACRIFICIAL SYMBOLS SCREAM: "SALVATION!"

Please scroll down for further articles

SACRIFICIAL SYMBOLS SCREAM: "SALVATION!"

Please scroll down for further articles

|

Salvation

The Latin adjective “salvus” or “salva” means “alive, safe, saved, well, unharmed, sound.” The Latin verb “salvare” means to “to save.” This “saving” can be natural or physical or it can be supernatural or spiritual. We get our word “salvation” from these Latin roots, which is why the dictionary defines “salvation” as “preservation or deliverance from harm, ruin, or loss.” This preservation, deliverance from harm, ruin, loss to be kept alive, safe, well, unharmed and sound, was at root of the Old Testament sacrifices. Even the pagans sacrificed to false gods in the hope of getting the same benefits. Yet there is only one God and His Providence provides for those needs—if we keep on the “good side” of Him. For a clear statement by God on what He expects of us, if we are to be on His “good side”, read chapter 26 of the Book of Leviticus—where God shows the two options in a way that cannot be misunderstood. The Old Testament Israelites—the once Chosen People of God—were told what they had to do for physical and spiritual “salvation”. On the one hand, they had to keep the Commandments of God and walk in His ways. On the other hand, they had to sacrifice to God in a variety and for a variety of reasons. If this was done, then God’s physical and material ‘salvation’ would be theirs, as well God’s supernatural and spiritual salvation. Let us then take a look at the notion, types, kinds, varieties of sacrifice and see what their purposes were. The Old Law Sacrifices were Figures of the Sacrifice of Christ All the sacrifices of the old law were figures of the sacrifice of our divine Redeemer, and there were four kinds of these sacrifices; namely, (1) the sacrifices of peace, (2) of thanksgiving, (3) of expiation, and of (4) impetration (“impetration” means “requesting” or “begging”). These four kinds of sacrifices are combined together in the New Testament Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, by what the Church calls “The Four Ends of the Mass”—namely: (1) adoration, (2) thanksgiving, (3) reparation, and (4) impetration. In the Old Testament… 1. The Sacrifices of Peace were instituted to render to God the worship of adoration that is due to him as the sovereign Master of all things. Of this kind were the holocausts. The duty of adoration—giving glory to God—is our first and foremost duty. How few people actually adore God—most just ask things from Him, and some make reparation (saying: “I’m sorry” an doing some penance). But these are all secondary obligations to that of adoration. 2. The Sacrifices of Thanksgiving were destined to give thanks to the Lord for all his benefits. We are quick to ask God for things, but very remiss and lukewarm in giving thanks for any things we might get! This reminds us of the Ten Lepers that Our Lord cured—and only one came back to give thanks! The word “Eucharist” comes from the Greek word “Eucharistia” meaning “Thanksgiving”. Is that our spirit? Do we really give thanks from the heart, or the lips? Do we give sufficient thanks, or merely a ‘microwaved’ version of thanksgiving: 2 minutes on the high setting? 3. The Sacrifices of Expiation were established to obtain the pardon of sin. This kind of sacrifice was specially represented in the Feast of the Expiation by the emissary-goat (scapegoat), which, having been laden with all the sins of the people, was led forth out of the camp of the Hebrews, and afterwards abandoned in the desert to be there devoured by ferocious beasts. This sacrifice was the most expressive figure of the Sacrifice of the Cross. Jesus Christ was laden with all the sins of men, as Isaias had foretold: “The Lord hath laid on Him the iniquity of us all” (Isaias 53:6). He was afterwards shamefully led outside the walls of Jerusalem to Calvary, to where the Apostle invites us to follow Him, by sharing in His shame and sufferings: “Let us go forth therefore to Him, outside the camp, bearing His reproach”! (Hebrews 13:13). He was abandoned to ferocious beasts; that is to say, to the Gentiles, who crucified Him. Let the ferocious worldly people turn on us if they wish, as we willingly lead ourselves outside the walls of the world to be with Christ on Calvary. 4. The Sacrifices of Impetration (meaning “Request”) had for their object to obtain from God His aid and His grace. There is probably nobody who fails in this regard—for all we ever seem to do is ask God for this, for that, for everything. Now, all these sacrifices were abolished by the coming of the Redeemer, because only the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, which was a perfect sacrifice, while all the ancient sacrifices were imperfect―being merely types or figures of the future sacrifice of Christ—which was to be perfect and sufficient to expiate all the sins, and merit for man every grace. Thus these sacrifices, by pleasing God, getting on His "good side" brought about a wide ranging salvation: a preservation, deliverance from harm, ruin and loss, in order to be kept alive, safe, well, unharmed and sound. The Requirements of the Sacrificial Victim When we go out to buy something, we have a check-list of points that we expect to be met before we commit to buying an object. The same is true of God. There are certain conditions He expects to see in a sacrifice before He will accept it. The Old Law required five conditions with regard to the victims which were to be offered to God, so as to make them agreeable to him. These five conditions were (1) sanctification, (2) oblation or offering, (3) immolation or destruction, (4) consumption, and (5) participation. 1. Sanctification The victim had to be sanctified, or consecrated to God, so that there might not be offered to him anything that was not holy, nor unworthy, of his majesty. Hence, the animal destined for sacrifice had to be without stain, without defect; it was not to be blind, lame, weak, nor deformed, according to what was prescribed in the Book of Deuteronomy (15:21). This condition indicated that such would be the Lamb of God, the victim promised for the salvation of the world; that is to say, that he would be holy, and exempt from every defect. We are thereby instructed that our prayers and our other good works are not worthy of being offered to God, or at least can never be fully agreeable to him, if they are in any way defective. Moreover, the animal thus sanctified could no longer be employed for any profane usage, and was regarded as a thing consecrated to God in such a manner that only a priest was permitted to touch it. This shows us how displeasing it is to God if persons consecrated to him busy themselves, without real necessity, with the things of the world, and thus live in distraction and in neglect of what concerns the glory of God. Sanctification is our target and goal in life—yet many neglect it, scorn it, mock it and pay little or no attention to obtaining it. Woe to those people, for God says in Holy Scripture: “I am the Lord your God! Be holy because I am holy! Defile not your souls … You shall be holy, because I am holy!” (Leviticus 11:44-46). Our Lord echoes this in the New Testament, saying: “Be you therefore perfect, as also your heavenly Father is perfect!” (Matthew 5:48). This holiness is stressed in the very title of the sacrifice that Christ left behind for us—the HOLY Sacrifice of the Mass, which is the PERFECT Sacrifice, and which is meant to make us HOLY and PERFECT. Is that how we see the Mass? Do we seek to fulfill this condition of HOLINESS and SANCTIFICATION? 2. Oblation or Offering The victim had to be offered to God; this was done by certain words that the Lord himself had prescribed. The sacrifice was to be totally God’s, with nothing held back. We all make a morning offering as a part of our prayers, but is it true offering, a true oblation? Or do we hold something back? “Jesus, I give you this, but I cannot bear to give you that!” This reminds of the offering Jesus requested of the rich young man: “And behold one came and said to Jesus: ‘Good master! What good shall I do that I may have life everlasting?’ Who said to him: ‘If thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments!’ The young man saith to Him: ‘All these I have kept from my youth, what is yet wanting to me?’ Jesus said to him: ‘If thou wilt be perfect, go sell what thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in Heaven: and come follow Me!’ And when the young man had heard this word, he went away sad: for he had great possessions” (Matthew 19:16-22). He was prepared to give up some things, but not everything—yet everything he had, was ultimately given to him by God! God was the real owner of the young man’s great possessions! Alas, are we not of the same type? God wants all and that is why the first Commandment is “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, with thy WHOLE heart, and with thy WHOLE soul, and with thy WHOLE mind, and with thy WHOLE strength. This is the first commandment” (Mark 12:30). Whole means total—total offering, total sacrifice! 3. Immolation or Destruction It had to be immolated, or put to death; but this immolation was not always brought about by death, properly so called; for the sacrifice of the loaves of proposition, or show-bread, was accomplished, for example, without using iron or fire, but only by means of the natural heat of those who ate of them. Our Lord seems to ask for this immolation or destruction from us, as reported by all of the Evangelists in one form or another, when He says: “For he that will save his life, shall lose it: and he that shall lose his life for my sake, shall find it” (Matthew 16:25) … “For whosoever will save his life, shall lose it: and whosoever shall lose his life for my sake and the gospel, shall save it” (Mark 8:35) … “For whosoever will save his life, shall lose it; for he that shall lose his life for my sake, shall save it” (Luke 9:24) … “Whosoever shall seek to save his life, shall lose it: and whosoever shall lose it, shall preserve it” (Luke 17:33) … “Amen, amen I say to you, unless the grain of wheat falling into the ground die, [25] Itself remaineth alone. But if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit. He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world, keepeth it unto life eternal” (John 12:24-25). “Then shall they deliver you up to be afflicted, and shall put you to death: and you shall be hated by all nations for My Name’s sake” (Matthew 24:9). Is that how we see our life? Is that how we are prepared to live our Faith? A total immolation for Christ’s sake? Few there are who do this—but few there are who are saved! Is there a connection? Most probably! 4. Consumption The victim had to be consumed. This was done by fire. The sacrifice in which the victim was entirely consumed by fire was called holocaust. The latter was thus entirely annihilated in order to indicate by this destruction the unlimited power that God has over all his creatures, and that as he created them out of nothing, so he can reduce them to the nothingness from which they came. In fact, the principal end of the sacrifice is to acknowledge God as a sovereign being, so superior to all things that everything before him is purely nothing; for all things are nothing in presence of him who possesses all things in himself. The smoke that came from this sacrifice and arose in the air signified that God received it as a sweet odor, that is to say, with pleasure, as is written of the sacrifice of Noe : “Noe ... offered holocausts upon the altar; and the Lord smelled a sweet savor” (Genesis 8:20). Our spiritual consumption is a consumption by a fire of a different kind—the fire of love! God is love—“God is charity” (1 John 4:8)—and we are told: “Love the Lord thy God, with thy WHOLE heart, and with thy WHOLE soul, and with thy WHOLE mind, and with thy WHOLE strength!” (Mark 12:30). God has often chosen fire to symbolize Himself: the fire of the burning bush that Moses saw; the pillar of fire that led the Israelites through the desert by night; the fire that set the mountain top ablaze in those desert wanderings; the fire that ignites the sacrifice of Elias on Carmel; the tongues of fire manifesting the Holy Ghost at the first Pentecost; the fire emanating from the Sacred Heart of Jesus, etc. We even ask to set ablaze when we pray to the Holy Ghost: “Come O Holy Ghost and enkindle in us the fire of Thy love!” But do we really mean it? Do we want to be consumed with love, by love, for love? 5. Participation All the people, together with the priest, had to be partakers of the victim. Hence, in the sacrifices, excepting the holocaust, the victim was divided into three parts, one part of which was destined for the priest, one for the people, and one for the fire. This last part was regarded as belonging to God, who by this means communicated in some manner with those who were partakers of the victim. Do we participate properly, not only in the Sacrifice of the Mass, but in all our sacrifices? The Mass has three essential parts—the Offertory (Oblation), the Consecration (Immolation) and Communion (Consumption). Do we participate fully in the Mass so that it really can bring about our sanctification? Or are we just there in body, but not really in spirit. Do we just go through the motions? The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass screams out “Salvation” every time it is offered—yet it seems that those screams are not loud enough to wake up most people to the purpose of the Mass. The Paschal Lamb These five above conditions ― sanctification, oblation, immolation, consumption and participation ― are found reunited in the Old Testament Sacrifice of the Paschal Lamb, which was a prefiguration of the Holy Sacrifice of Christ on Calvary and in the Mass. The Lord had commanded Moses (Exodus 40:3) that, on the tenth day of the month on which the Jews had been delivered from the slavery of Egypt, a lamb of one year and without blemish should be taken and separated from the flock; and thus were verified the conditions enumerated above, namely: 1. The separation of the lamb signified that it was a victim consecrated to God; 2. This consecration was succeeded by the oblation, which took place in the Temple, where the lamb was presented; 3. On the fourteenth day of the month the immolation took place, or the lamb was killed; 4. Then the lamb was roasted and divided among those present; and this was the partaking of it, or communion; 5. Finally, the lamb having been eaten, what remained of it was consumed by fire, and thus was the sacrifice consummated. |

Article 5

PIECING TOGETHER THE JIGSAW OF SACRFICES

Please scroll down for the latest article

PIECING TOGETHER THE JIGSAW OF SACRFICES

Please scroll down for the latest article

|

Not Enough Said About the Holy Mass

The Catholic Church, speaking through the Council of Trent, as through a mouthpiece, commands her preachers, and all others having the care of souls, to explain the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass to their people carefully and frequently. Our good Mother, the Church, has made this law, my dear Christians, to the end that we may all know what a great treasure God has left to us in this sublime Sacrifice of the Altar, and what great advantages we may derive from a faithful and devout attendance thereat. The same sweet love for men which pressed our Lord Jesus Christ, in the first instance, to institute this adorable Sacrifice of the New Law, presses Him, also, to desire that its transcendent nature and effects should be made known to the whole world as fully and as clearly as possible. The Sacrifice of the Mass is by far the richest treasure which Christ has left to His Church. Yet, there are many persons who treat it with indifference, and take little or no pains to rightly understand its value, or the manifold graces and blessings which it contains. Strange to say, among the few Catholics who frequently meditate upon the infinite love of Jesus Christ in instituting the Blessed Eucharist as a Sacrament, few of those few ever reflect upon His equally infinite love in the Sacrifice. By sacrifice is meant: the external offering to God alone, of some sensible or visible thing, made by a priest, or lawful minister; the partial destruction or total annihilation of the victim being the acknowledgment of Almighty God’s supreme dominion over us, and our total dependence on Him. Christian sacrifice cannot be offered to any one but to God alone. What is a Sacrifice? A sacrifice is the offering of a victim by a priest to God alone, and the destruction of it in some way to acknowledge that He is the Creator of all things. The strongest instincts of human nature prompt us to offer sacrifice to the Deity as an essential and acceptable act of religion. By his very nature man wants to adore and thank his Creator. Hence, from the commencement of the world, all nations, even the most barbarous and illiterate, have offered sacrifice of one kind or another to the divinities they worshiped. Men mistaken at times about the nature of the true God have offered false worship; but they have always recognized the obligation of adoring the Supreme Being. As far back as the history of man is recorded, there is evidence that men acknowledged their dependence on the Supreme Being by offering sacrifices to Him. Old Testament Sacrifices Before the coming of Christ, in the Old Testament Law, sacrifices of different kinds were frequently offered to God. The patriarchs and Jewish priests at the command of God offered fruits, wine, or animals as victims. Cain, for example, offered fruits; Abel offered some sheep of his flock; Melchisedech offered bread and wine. The destruction of these offerings, removed them from man’s use, they were destroyed and offered to God and thereby signified that God is the Supreme Lord and Master of the entire created universe and that man is wholly dependent upon Him for everything. Sacrifice, therefore, is the most perfect way for man to worship God. Yet all these different sacrifices of the Old Law were only figures of the sacrifice which Christ was to make of Himself. His offering of Himself on the cross was the greatest sacrifice ever offered to God. All the sacrifices of the Old Law derived their efficacy, or value, from the sacrifice which Christ was to offer on the cross. ● Abel offered sacrifice of “the firstlings of his flock” (Genesis 4:4). Abel is shown to be a type of Christ in that he was the first one to suffer for righteousness sake: “Behold I send to you prophets, and wise men, and scribes―and some of them you will put to death and crucify, and some you will scourge in your synagogues, and persecute from city to city: That upon you may come all the just blood that hath been shed upon the earth, from the blood of Abel the just, even unto the blood of Zacharias, whom you killed between the temple and the altar” (Matthew 23:34-35). The hostility that Cain directed toward his brother was ultimately meant for God. Abel died because he worshiped God rightly. Jesus died because He always did the will of His Father in Heaven. Abel was the first martyr. Jesus is the anti-typical martyr. St. Paul tells us that “the blood of Jesus speaks better things than that of Abel” (Hebrews 11:4; 12:24). So Abel was a type of Christ by way of comparison and contrast. He is compared with Christ in that he was martyred for righteousness; he is contrasted with Christ in that his blood cried out for vengeance while Christ’s blood cries out for mercy. ● Noe building his ark was a symbol of both the Temple of Old Testament and the Tabernacle in the New Testament. God dwelt in the Temple (and the Holy of Holies) and Christ dwells Eucharistically in the tabernacle of the new temple, the church. Noe also built an altar of sacrifice after the Great Flood: “And Noe built an altar unto the Lord: and taking of all cattle and fowls that were clean, offered holocausts upon the altar. And the Lord smelled a sweet savor” (Genesis 8:20-21). ● The priest and king, Melchisedech, sacrifices bread and wine, symbols of the future Eucharist: “Melchisedech the king of Salem, bringing forth bread and wine, for he was the priest of the most high God” (Genesis 14:18). Melchisedech was both king and priest, as we know Christ to be. He was the king of Salem (later to be called Jerusalem) and also a priest of God most high, who offered bread and wine and blessed Abram (later to be renamed Abraham) when he was returning from having rescued Lot from captivity. Melchisedech is both king and priest, as we know Christ to be. The name Melchisedech means, “my king of justice” or “my king of righteousness.” Jesus is truly the just king, the truly righteous One. Melchisedech is the king of the city of Salem, which would later be called Jerusalem. Jesus would make his triumphal entry into Jerusalem as king and be proclaimed a king and admit to being a king. “Behold thy king cometh to thee, meek, and sitting upon an ass” (Matthew 21:5). Asked by Pontius Pilate if He was a king, Jesus replied: “Thou sayest that I am a king. For this was I born, and for this came I into the world!” (John 18:37). It is in Jerusalem that Jesus would come to be mocked by the words, “Hail, King of the Jews” (Matthew 27:29). It is here, in Jerusalem, that as King and Priest he would offer gifts of bread and wine, consecrating them into His own Body and Blood, during the Passover at the Last Supper. Then, as King and Priest, He would offer the sacrifice of His life, thus blessing all of humanity and the descendants of Abram. ● Abraham “came to the place which God had shown him, where he built an altar, and laid the wood in order upon it: and when he had bound Isaac his son, he laid him on the altar upon the pile of wood, and he put forth his hand, and took the sword, to sacrifice his son. And, behold, an Angel of the Lord from Heaven called to him, saying: Abraham, Abraham ... Lay not thy hand upon the boy, neither do thou anything to him; now I know that thou fearest God, and hast not spared thy only-begotten son for my sake. Abraham lifted up his eyes, and saw behind his back a ram amongst the briers, sticking fast by the horns, which he took and offered for a holocaust instead of his son” (Genesis, chapter 22). ● Elias, too, built an altar to the name of the Lord ... “and laid the wood in order, and cut the bullock in pieces, and laid it upon the wood. .. .And when it was now time to offer the holocaust, Elias, the prophet, came near, and said: ‘O Lord, God of Abraham, and Isaac, and Israel, show this day that Thou art the God of Israel, and I Thy servant: and that according to Thy commandments I have done all these things!’ ... And when all the people saw this, they fell on their faces, and said: ‘The Lord He is God, the Lord He is God!’” (3 Kings, chapter 18) The sacrifices of the Old Law were, some of them, bloody; others unbloody. The bloody sacrifices consisted chiefly of lambs, oxen, and goats. Sometimes, as in the case of our Lord’s presentation, the victims were birds: “They carried him to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord ... And to offer sacrifice, according as it is written in the Law of the Lord, a pair of turtle-doves or two young pigeons” (Luke 2:22-24). The unbloody sacrifices were mainly of flour, and wine, and oil, etc. These ancient sacrifices, though offered up by the hands of the holy Patriarchs, had no internal value of their own. They were but poor and weak elements, quite incapable of cancelling sin, quite incapable of conferring God’s grace upon those who offered them, or upon those for whom they were offered. “For it is impossible,” says St. Paul, “that with the blood of oxen and goats, sins should be taken away” (Hebrews 10:4). Those sacrifices were but mere types and figures of the true Sacrifice yet to come―that is, of the holy Mass―and it was only as such that they were in any sense acceptable to God. Compared with the Sacrifice of the Mass, they were but as vague shadows, compared to the solid substance. |

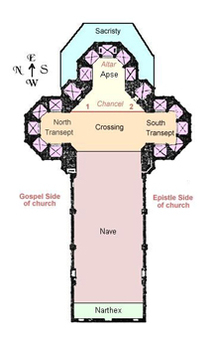

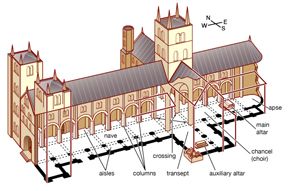

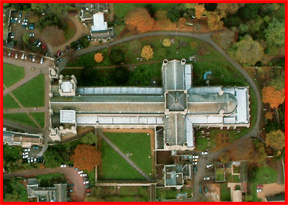

Article 6

THE TEMPLE AND THE CHURCH

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

THE TEMPLE AND THE CHURCH

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

|

Before the Temple of Jerusalem