| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE NAME OF THE SAINT YOU WISH TO VIEW

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

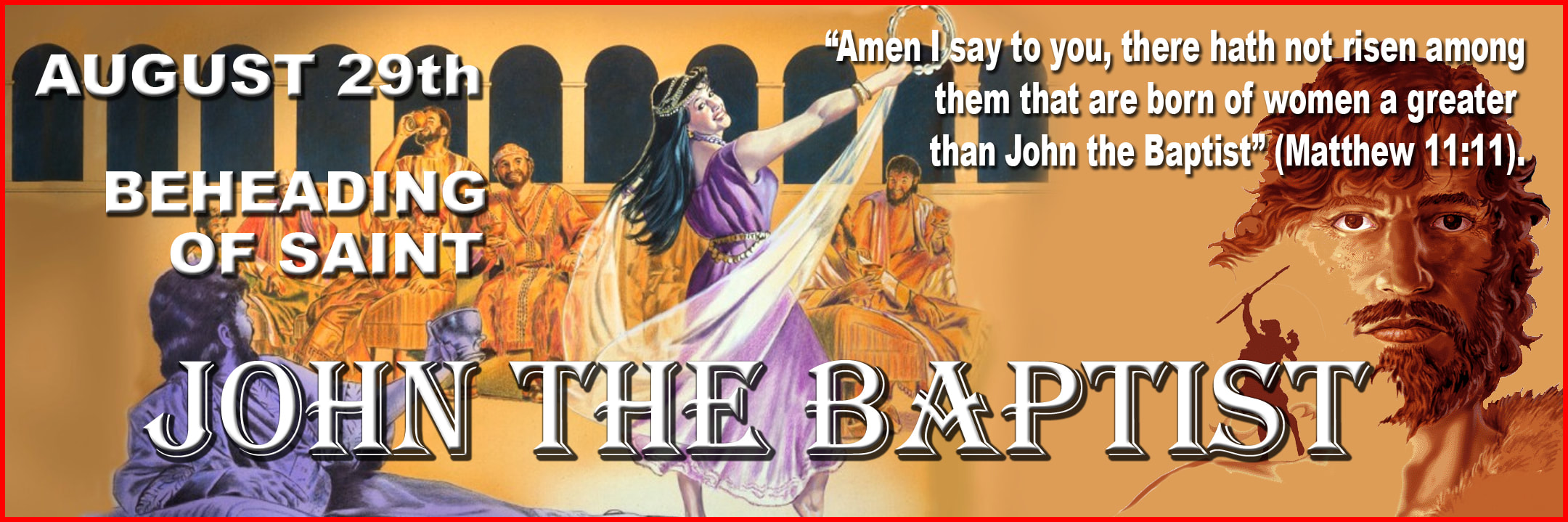

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST

|

The son of Zachary, a priest of the Temple in Jerusalem, and Elizabeth, a kinswoman of Our Lady who visited her, he was probably born at Ain-Karim southwest of Jerusalem after the Angel Gabriel had told Zachary that his wife would bear a child even though she was an old woman. He lived as a hermit in the desert of Judea until about A.D. 27.

When he was thirty, just as Our Lord, he began to preach on the banks of the Jordan against the evils of the times and called men to penance and Baptism “for the kingdom of Heaven is close at hand.” He attracted large crowds, and when Christ came to him John recognized Him as the Messiah and baptized Him, saying, “It is I who need Baptism from You” (Matthew 3:14). When Christ left to preach in Galilee, John continued preaching in the Jordan Valley. Fearful of his great power with the people, Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Perea and Galilee, had him arrested and imprisoned at Machaerus Fortress on the Dead Sea when John denounced his adulterous and incestuous marriage with Herodias, wife of his half-brother Philip. John was beheaded at the request of Salome, daughter of Herodias, who asked for his head at the instigation of her mother. John inspired many of his followers to follow Christ when he designated Him “the Lamb of God,” among them Andrew and John, who came to know Christ through John’s preaching. John is presented in the New Testament as the last of the Old Testament prophets and the precursor of the Messias. 1. The Coming of John the Baptist It was the fullness of time. That strange, unruly people had waited long. Jericho, as they passed it on their way to and from the Holy City, had stood there through the centuries, to remind them forever of that day when Josue had brought their fathers into the land that flowed with milk and honey. They had entered that land, they had spread over it, they had made it their own, and they had all but perished in it. They had established in it the one God Who had made them His chosen people, they had built His temple on Moria to be the wonder of the world; and yet across the valley to the south was the Hill of Scandal, where he who had built the first temple to their one, true God, had built other temples to other gods in the days of his undoing. They had served their God and had forsaken Him; by Him they had been punished, even to destruction, and yet ever and again the bones of their dead past had been revived. It was a weird tale that they had to recall; a tale of a stiff-necked people, faithless more often than faithful, nevertheless with a something in it that kept it alive, and united, and conscious of itself as the race that must one day save the world. The city of David had perished, but another had been built on its site. Solomon’s temple had gone, but in its place another had arisen. The very sacred books had been lost but had been found again, and now they were studied as they had never been before. As for their ancient oppressors, Egypt lay buried in its own waste of sand; the Philistines had sunk in the sea; Babylon, Assyria, were names that attached themselves to monster ruins; Antiochus and his Greeks had vanished again as quickly as they had come. There remained the Romans, the contemptuous, hated Romans; but their day would come, they had sealed their own doom, for had they not violated the Holy of Holies? And there were their myrmidons, the creatures neither Jew nor Roman, Herod and Philip and Lysanias, whom everybody loathed and felt the shame of obeying; surely they had sunk as low as they well could, surely the dawn was at hand. It had always been so; always the Lord had at last remembered mercy; He would do it again. And yet in what could they hope? They looked at their Temple, gleaming gold beneath the autumn sun, and it filled them with pride; still could they not forget that it had been built, not by Solomon, not by Esdras, but by the bloodstained Herod. Because David had been a man of blood he had been forbidden to build the first temple; how much worse had been Herod! THE PROPHET ISAIAS They went into its courts and worshiped; yet had they to close their eyes to much before in His own house they could commune with their God. They sat at the feet of their teachers and they came away confused. Their scribes bound them down to the letter of the Law; their doctors were divided into schools and confounded one another; their very priests were the puppets of the Roman hand, politic, untrue, grasping, confined now to a single family, with the old man Annas as the guiding star of all. The Law had divorced itself from life; religion had become a binding bondage; men looked with hungry eyes from their city walls towards the eastern hills as the sun rose beautiful above them, and longed and longed again that at length there might come up to them from across the Jordan that other Savior Who was to bring them light. That He would come they knew; they could never doubt it. Their whole history foretold it; again and again their prophets had said it; above them all the greatest of their prophets, Isaias. They knew his words by heart; they were steeped in his majestic poetry, his language of mystery they had pondered in their schools. One passage more than all others they could never forget, so glorious was it, so absolute, so reassuring. Their king that was to be would one day come, so it said, and His herald would announce Him. “ ‘Be comforted, be comforted, My people!’ saith your God. ‘Speak ye to the heart of Jerusalem and call to her, for her evil is come to an end. Her iniquity is forgiven. She hath received of the hand of the Lord double for all her sins.’” Then had the prophet taken his imagery from the grand progresses of the monarchs of old. A runner would go forward to proclaim the king’s coming; mountains would be leveled, valleys would be filled, to make easy his approach. “The voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord! Make straight in the wilderness the paths of your God! Every valley shall be exalted and every mountain and hill shall be made low! And the crooked shall become straight and the rough ways plain and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh together shall see that the mouth of the Lord hath spoken.’” Along that leveled road would come the herald, telling the imminent presence of the king: “The voice of one saying: ‘Cry!’ And I said: ‘What shall I cry?’ ‘All flesh is grass and all the glory thereof as the flower of the field the grass is withered and the flower is fallen but the word of the Lord endureth for ever! Get thee up upon a high mountain, thou that bringest good tidings to Sion! Lift up thy voice with strength, thou that bringest good tidings to Jerusalem! Lift it up, fear not! Say to the cities of Juda: “Behold your God”.’” Last of all, in might and in meekness, would come the monarch Himself: “Behold the Lord shall come with strength and His arm shall rule! Behold His reward is with Him and His work is before Him! He shall feed His flock like a shepherd! He shall gather together the lambs with his arm and shall take them up in His bosom and He shall Himself carry them that are with young” (Isaias 40:1-11). On words like these men dreamed in and about Jerusalem. At length, in the midst of such a wistful, waiting, hungering world, “The word of the Lord came to John, the son of Zachary, in the desert and John the Baptist came baptizing and preaching in the desert of Judæa and into all the country about the Jordan. Preaching the baptism of penance for the remission of sins and saying: ‘Do penance! For the kingdom of Heaven is at hand!’” To very many, when he first appeared, John could not have been unknown. There were those who had heard the wonderful things connected with his birth; his father Zachary and his mother Elizabeth were too prominently placed for that event to be easily forgotten. Moreover, the behavior of John himself had kept it well before them. From the first he had lived his life aloof: “And the child grew and was strengthened in spirit and was in the deserts until the day of his manifestation in Israel.” He had lived in the deserts of Judæa, yet not so far away but that men might find him if they would; and the fascination of the hermit, the fascination that surrounds all lonely souls, had already drawn men to him. But now he began to move; he began to assume a new role. Though he clung about the neighborhood of the city, and still loved the desert places, yet was he often found upon the high roads that passed through them, especially the great main road that led up from the Jordan to Jerusalem. Moreover, his preaching had taken a new turn. Whatever before it had been, now deliberately he proclaimed himself a prophet, a herald of a coming kingdom. He spoke with a new and independent authority; reverent as he was, he assumed a position of his own. He proclaimed a new beginning, repentance for the past, bringing back religion into life; he took hold of the old ceremonial of baptism, as a sign of sorrow, and forgiveness, and reform, and gave it a fresh significance. It is important here to notice the place which John held in the minds of the people; important because upon it depends much of the action of Jesus in His early public life. While John was prominent on the scene, Jesus bided in the background; only when John was removed did He come actively forward. The death of John was, it would seem, coincident with the first mission of the twelve Apostles; the last appeal to the Jews in the temple, before Jesus finally left it, was made in the name of John. 1. One evangelist gives to his birth a prominence greater than he gives to that of Jesus Himself. Much more than half of St. Luke’s first chapter is occupied with it; the story of Our Lord’s conception and nativity is more shortly told, and, except for the appearance of the Angels to the shepherds, there is less of the wonderful, more of the commonplace, in the whole narration. 2. Three evangelists point to him as the first great fulfillment of Messianic prophecy, while the fourth lifts him to a rank unique among all the prophets. It would be difficult to speak of any man with greater solemnity than this: “There was a man sent from God whose name was John. This man came for a witness to give testimony of the light that all men might believe through him. He was not the light, but was to give testimony of the light” (John 1:6-8). 3. Lastly Jesus Himself speaks of him in terms which raise him above any other man that has lived. “And when the messengers of John were departed He began to speak to the multitudes concerning John: ‘What went ye out into the desert to see? A reed shaken with the wind? But what went ye out to see? A man clothed in soft garments? Behold they that are in costly apparel and live delicately, are in the houses of kings! But what went ye out to see? A prophet? Yea, I say unto you and more than a prophet! This is he of whom it is written: “Behold I send My Angel before thy face who shall prepare the way before thee!” For I say unto you among those who are born of women, there is not a greater prophet than John the Baptist!’” (Matthew 11:7-11. Luke 1:24-28). Nor was this the only occasion; at another time He spoke of him as “A burning and a shining light” (John 5:35) and yet again as “Elias that is to come” (Matthew 11:14). 4. To all this must be added the extraordinary reverence paid to the name of John throughout all this period, which continued steady and unabated even when the name of Jesus had waned. For instance: 1. On this account, though he held him prisoner, Herod hesitated to execute him: “Having a mind to put him to death He feared the people because they esteemed him as a prophet.” (Matthew 14:5). 2. While he was in prison his disciples never ceased to keep him informed of all that was going on in Galilee: “And John’s disciples told him Of all these things.” (Luke 7:18). 3. They followed his advice in their attitude to Jesus Himself: “John the Baptist sent us to see Thee saying: ‘Art thou He that art to come or look we for another?’” (Luke 7:20). 4. After he had been put to death his disciples did honor to his body: “Which his disciples hearing, they came and took his body and buried it in a tomb and came and told Jesus” (Matthew 14:12; Mark 6:29). 5. After his death Herod his murderer lived in constant fear of him: “Now at that time Herod the tetrarch, heard the fame of Jesus and of all the things that were done by Him. And he said to his servants: ‘This is John the Baptist! He is risen from the dead and therefore mighty works show forth themselves in Him!’ And he was in doubt, because it was said by some that John was risen from the dead; but by other some that Elias hath appeared; and by others that one of the old prophets was risen again. Which Herod, hearing, said: ‘John I have beheaded! But who is this of whom I hear such things? John whom I beheaded, he is risen from the dead! And he sought to see him” (Matthew 14:1-2; Mark 6:14-16; Luke 9:7-9). 6. At a much later date his evidence for Jesus is quoted in Judæa as being more convincing even than miracles: “And He went again beyond Jordan unto that place where John was baptizing first and there He abode and many resorted to Him and they said: ‘John indeed did no sign, but all things whatsoever John said of this man, were true and many believed in Him” (John 10:40-42). 7. On the very last day of His public teaching Jesus is able to confute His enemies by an appeal to the baptism of John: “For all men counted John that he was a prophet indeed” (Matthew 21:23-27; Mark 11:27-33; Luke 20:1-8). 8. Years afterwards, when the Church had spread far abroad, disciples of John are still to be met with who, “Being fervent in spirit, spoke and taught diligently the things that are of Jesus, knowing only the baptism of John” (Acts 18:25). Though this coming of John need not at first have seemed very remarkable, for others of his kind had from time to time appeared, still there was that about him and his preaching which differentiated him from all the rest. Above all was his method different from that of the spiritual leaders whom the men of Judæa had been wont to follow. These came before them particular in their dress, their fringes and their phylacteries, conforming with exaggerated detail to their interpretation of the Law. He discarded all this; he would not even heed common convention. He would clothe himself with just that which came first to hand; he would eat just that which nature placed within his reach in the wilderness, and nothing more. “And the same John had his garments of camel’s hair and a leathern girdle about his loins and his meat was locusts and wild honey” (Matthew 3:4). His preaching, too, was different. Their guides taught them the details of the Law and its minute obligations placing in their observance the height of sanctity. John never mentioned these; he broke right through them and dived into the very hearts of men. He appealed to their inner knowledge of themselves, of right and wrong, of good and evil, truth and falsehood. If they would have ceremonial, then let it be such as declared the soul, true acknowledgment of evil done, true reform of life, true preparation for whatever was to come. Preaching such as this soon began to tell. Travelers up to Jerusalem, merchants from the East, pilgrims coming to the festivals, would look at this strange figure, and listen for a while, and pass by. They might affect to disregard him; they might call this man but another fanatic revivalist; they might say the things he taught were of no concern to them; busy, preoccupied as they were, they might resent the intrusion as unwarranted, vulgar, unseemly. Still would the chance words they heard refuse to leave them; they had pierced their hearts and their consciences and would not be quieted. These men went on their way they talked among themselves; they linked this teaching up with the teaching of the Law, and saw that it gave the Law new life. Gradually they came back, bringing other with them; some only curious to see this new phenomenon some in timid hope that here might be a new beginning; some, who had hungered for long years, seeing already in this sudden revelation a sign that the day of salvation was at hand. They came and they were conquered; they came to learn and they discovered themselves. From the city they came and from the hill country round about; they would not return till by an open avowal they had confessed their belief in this man. “Then went out to him all the country of Judaea and all they of Jerusalem and all the country about Jordan and they were baptized by him in the river Jordan, confessing their sins.” Such a movement could not fail soon to attract those in authority, the guardians of the Law, the doctors in Israel, the men who, first among all, were to recognize and welcome the Messias when He came. They knew the signs, they interpreted the prophets; when they were fulfilled it would be for them to judge; in the meantime they were the masters, of Israel and of its Temple. Of course this John, whoever he might prove to be, must never be allowed to interfere with their prerogative. On the other hand so long as there was no sign, and little fear of that, he might be countenanced; out of such revivals usually grew a greater observance in the Temple. They would go down to him themselves; they would support the movement by their presence; by their own submission to this ceremonial of the Baptist they would give it a mark of their approval. In this way at least they would keep a hold upon this new preacher, whom already it might be dangerous to oppose. But the Baptist was not to be deceived. Not for nothing had he spent his years of preparation in the desert, studying men, learning men as only he can learn them who leads his life apart, sifting the truth from the falsehood of their ways. Not for nothing had he searched the Scriptures, and separated grain from chaff. The specious defense that these people held up before themselves, that they were the children of Abraham, that they were the chosen of God, that they were therefore secure from rejection, must be broken down if the “way of the Lord” was to be made straight. Plainly and at once they must be told of their crafty nature, of their blind self-deception, of the emptiness of their claim. If they would rightly inherit their birthright there must be truth to the core; there must be a renewal of the inner man, there must be no make-belief, no substitute of outward show for sincerity. The fruits they produced must be from themselves, not from the hollow fulfillment of a hollow Law. He spoke alike to all, but it was to the Pharisees and scribes mingled with the crowd that his words were specially addressed. Mercilessly he spoke to them; from the beginning there should be no mistake. After submission of heart, the one great mountain to be leveled before the Lord could come to His Own was the hardened refuse piled up and trodden down about the Law. “And seeing many of the Pharisees and Sadducees, coming to his baptism, he said to the multitudes that came forth to be baptized by him: ‘Ye brood of vipers! Who hath shewed you to flee from the wrath to come? Bring forth therefore fruits worthy of penance! And do not begin to say within yourselves “We have Abraham for our father!” For I say to you that God is able of these stones to raise up children to Abraham. For now the axe is laid to the root of the trees. Every tree therefore that bringeth not forth good fruit Shall be cut down And cast into the fire.” Language such as this was not to be mistaken. From the outset John threw down the gauntlet, refusing to parley; it was a declaration of war with a definite enemy, which was to end only on Calvary. The people heard, but the significance of the challenge passed them by. They were too much concerned with themselves to take much heed of the Pharisees and Scribes; it was enough for them that the Baptist taught the need of “fruits worthy of penance.” They asked for further light and guidance. They were a motley crew, for the most part men of no particular religious reputation; common men, tax-collectors bearing an ill name, soldiers restless and discontented, whose power and position gave them opportunity for every kind of evil, poor folk from the country-side, not over-burdened with intelligence, still more wanting in instruction, whose hard lives had closed their hands to their neighbors and had killed in them the first elements of love. But they wished to rise to better things; and here was one who would teach them how they might do it. They asked him, and to them John altered his tone; treated them tenderly as sheep that had no shepherd; imposed on them no burden heavier than they could bear; simply, in language of their own, told them just the duties of their state of life. In these last words of counsel there is a gentleness and sympathy or nature which goes far to explain the hold of John upon the people; it is an anticipation or Him Who “Would not crush the broken reed And smoking flax would not extinguish.” “And the people asked Him saying: ‘What then shall we do?’ And He answering said to them: ‘He that hath two coats, let him give to him that hath none and he that hath meat, let him do in like manner!’ And the publicans also came to be baptized and said to Him: ‘Master what shall we do?’ But He said to them: ‘Do nothing more than that which is appointed unto you!’ And the soldiers also asked Him saying: ‘And what shall we do?’ And He said to them: ‘Do violence to no man. Neither calumniate any man and be content with your pay.’” Can we now picture to ourselves this first appearance of the Baptist? He came into a world with an ancient tradition, with a belief, a conviction, that a great future lay before it, yet were both tradition and belief marred by the dross that had gathered round them. He came among men intent upon their own affairs, especially their own political affairs, in consequence suspicious, self-centered, prone to hatred. Religion for them was a rigid, stereotyped substitute form; against its claims and ever-growing tyranny many had long since begun to chafe, though they could not lay aside the old inheritance, nor rid themselves of its ceremonial, nor reject altogether the hope in the future which it gave. He came at a time when many, eager souls as well as souls that feared, were on the tip-toe of expectation, strained so far that they were in danger of despair. He came and stood in the desert by the river, at the gateway leading into Judæa, on the very spot that was still hallowed by the memory of the prophet Elias, hard upon the main road along which the busy world had to pass; a weird, uncouth, unkempt, terrible figure, in harmony with his surroundings, of single mind, unflinching, fearing none, respecter of no person, asking for nothing, to whom the world with its judgments was of no account whatever though he showed that he knew it through and through, all its castes and all its colors. He came the censor of men, the terror of men, the warning to men, yet winning men by his utter sincerity; telling them plainly the truth about themselves and forcing them to own that he was right; drawing them by no soft inducements, but by the hard lash of his words, and by the solemn threat of doom that awaited them who would not hear; distinguishing true heart-conversion from the false conversion of conformity, religion that lived in the soul from that sham thing of mere inheritance and law; going down into the depths of human nature in his ceaseless search for “the true Israelite in whom there was no guile.” An Angel and no man, fearless voice to which the material world seemed as nothing compelling attention, fascinating even those who would have passed him by, making straight the path through the hearts of men; cleansing, baptizing, pointing to truth, life, but as yet, until all was prepared, saying nothing of that Lord, Whose coming he was sent to herald, content to foretell only the Kingdom; John, the focus upon which all the gathered light of the Old Dispensation converge, from which was to radiate the light of the New. All this those felt who now began to ask, concerning themselves: “What then shall we do?” concerning him: “Who is he?”―crowds of every kind, publicans, soldiers, citizens from the great towns and country villages, patronizing Pharisees and submissive disciples. 2. The Prophecy of the Messias The minds of men being what they were, and the tension of the times so great, it was inevitable that questions should be asked concerning John himself. There was the evidence of his early life, and it was confirmed by the evidence of the present; men had found one in whom they believed, who spoke on his own authority, and not after the manner of the Pharisees and Scribes. The time was at hand; the Messias, so it was said both by the common folks and by those who ought to know, was due at any moment. When He came, He might well be expected to be such a one as John. The question was answered by a rumor; the rumor spread, growing ever more credible as the number grew that favored it. Was not John the anointed of the Lord, and would he not soon reveal himself? This was John’s opportunity. Hitherto he had spoken only of the Kingdom and of the preparation for it; now it was time to announce the King. These simple people had submitted to his baptism, and had thus proved their goodwill; he would take them further and show them that there was a Baptism yet to come which would put his own to naught. They had grown in devotion to himself; he would assure them that to the One Who was soon to stand amongst them he was not fit to be a slave. His own baptism was only of dead water; that which was to come would be of living spirit. His did but wash the outer surface, for the rest was a symbol and no more; that which was to follow would reach the very soul, would try it as gold is tried in the fire, would be a source of very life, not merely a sign of penance. He would tell them this, and he would tell it in language such as these simple country people could understand. Up the hill in the distance might be seen some husbandman at work, blowing away with his fan the chaff from his heap of corn, the rich grain purified settling on the floor beneath. It was a happy illustration for his purpose; it would emphasize each point, the utter purity of the Kingdom, the utter truth of the King, the blessedness of membership, the evil of rejection, the added sanction to the belief in eternal bliss or punishment, which had struggled to the light through the ages. “And as the people were of opinion and all were thinking in their hearts of John that perhaps he might be the Christ. John answered and preached saying unto all: ‘I indeed baptize you in water unto penance. But He that shall come after me Is mightier than I, Whose shoes I am not worthy to bear, the latchet of whose shoes I am not worthy to stoop down and loose. He shall Baptize you with the Holy Ghost and with fire. Whose fan is in His hand and He will thoroughly cleanse His floor and will gather His wheat into His barn’” Again let us sum up the impression, for on a clear understanding of this scene depends much that is to follow. With hearts lost to him these simple folk believed in John; given such sincerity they could not hold back. With their eyes of longing turned towards the future, to the sun that was to rise above the eastern hills, and with the light of the past shining red behind them, setting over Jerusalem and the mountains of Judaea. They could not but ask themselves whether at last the time had come; whether this singular man, who proclaimed a new Kingdom to be near, who knew the secret of its membership, were not indeed the Messias; whether the signs they were to look for were not upon him; the superhuman vision that made him a safe guide; the conquering conviction that compelled assent; the likeness to the prophets of old whose line had long since perished; the knowledge of hearts, the message of repentance, the opening of the way to new life, the insistence on utter truth, the contempt of formalism. Miracles and signs of that kind they did not expect, such things were not in their category; it was miracle enough that he baptized as with power and spoke as one having authority. In this spirit they had come to him, and he had received them. Tenderly, gradually he had led them higher, yet never yielding one whit of his sternness. Humbly, without fear of losing hold upon them, he had debased himself before the Light that was to come: “He was not the light but was to give testimony of the light.” Firmly he had repeated to them the need of preparation for its coming. Let there be no mistake; the Master Who is to come is One Who will not be deceived. He will see through the outward appearance; He will not be content with mere form; He will search the hearts of men, and will have no surface substitute; He will accept none but the true, the sincere, the genuine; He will not endure the husks with the grain, but will have that grain purified at whatever cost, even though with His Own hand He must waft the husks away. One can feel how and why John puts this utter truth of Jesus above all things else, utterly true Himself, seeking only utter truth in others, Whose work in the world would be to “bear witness to the truth” and to be believed, as John himself had been believed, on His Own authority alone. To a people grown stereotyped in form, to whom a species of self-deception had come to be considered a virtue, this was essentially John’s message, and was indeed “good tidings of great joy”. The Evangelists one and all imply that, if they would, they could say much more concerning John: “And many other things exhorting did he preach to the people.” But for the present this must be enough. More will yet follow; he is too important, his witness is too convincing, to be set aside with this single notice. Still it is sufficient that here he should be set before us, a gaunt figure on the horizon of the yellow-brown desert, the Judaean hills before him with the Holy City beyond, the Dead Sea with its memories of doom on his left down below, the sun rising over the hills of Moab and brightening the sky behind, while he stands between two eras, the link between the old and the new, the summary of the past and the foreshadowing of the future. 3. The Baptism of Jesus It is at this moment, and in the midst of circumstances such as these, that Jesus at length makes His appearance. There is no great disturbance, neither Nazareth nor Judaea notice it. It is the late season of the year, when the countryside is bare and work in the fields is less pressing. It is on the occasion of some festival, it may have been the feast of Tabernacles in October, when numbers make towards the Holy City. The news concerning John and his baptism has reached as far as Galilee, and a carpenter living at the upper end of Nazareth, with others who have long “waited for the consolation of Israel,” goes up by the ordinary route that runs alongside the Jordan, crossing the river into Judaea at the ford where John is preaching and baptizing. Like the rest of the band of pilgrims He stops at the ford to listen to the earnest preacher; like others who have come well-disposed, when the preaching is over, He draws nearer and adjusts His clothing to take the step which is proof of a sinner’s submission. He waits till all the rest are baptized, yielding to the eager throng that presses forward, Himself easily unnoticed and pushed aside; then, the very last in the group of penitents that day, He Himself walks into the water. This is the simple matter of fact as the evangelists give it to us. There is not, and obviously during the last eighteen years there has not been, the least indication that Jesus of Nazareth is anything more than any of the men standing round Him. Even John on a later occasion declares that at first he did not know Him Who He was; for that even he required a direct revelation from above. “And John gave testimony saying I saw the Spirit coming down as a dove from Heaven and He remained upon Him and I knew Him not but He who sent me to baptize in water said to me: ‘He upon Whom thou shalt see the Spirit descending He it is that baptizeth with the Holy Ghost.’ And I saw and I gave testimony that this is the Son of God.” (John 1:32-34). Still, already before the revelation was given, naturally, Instinctively, John stayed his hand; he hesitated to baptize. Though he knew not all that Jesus was, yet as a relative he knew Him. He knew the story of His birth, so intimately connected with his own he knew what his own mother had said of Him; if before he was born he had leaped for joy at His coming, now when they met he could not fail to be stirred. Whoever Jesus was, John knew He was no sinner, and this baptism was not for such as He; whoever He was, by comparison with Him John himself could scarcely be called clean. Was His coming then a sign that it was time for him to yield, and allow this better man to take his place? He stayed his arm; he made a sign of protest; for a moment he held Jesus back. “But John stayed Him saying: ‘I ought to be Baptized by Thee and comest Thou to me?’” The answer of Jesus confirmed the recognition; it was the answer of one man to another whom He knew and who knew Him. It was also an answer of command; Jesus did not hide from John that He understood, and accepted the honor done to Him. Though He submits, yet is He the Master; it is the same Jesus, acting in precisely the same way as the Jesus of eighteen years before in the Temple, Master of His Mother and Joseph, yet afterwards in all things “subject to them.” Though He stands there in the stream to be baptized, yet the baptism is not given without His order; it is the same Jesus as, three years later, was the Jesus of Calvary Who submitted unto death yet laid down His life when and as He chose and in no other way. Thus though the words He speaks are those of complete subjection, nevertheless there is in them the authority and firmness of one Who had a mission to fulfill and Who knew exactly all that it included; before the Spirit came upon Him Jesus knew. “And Jesus answering said to him: ‘Suffer it to be so now. For so it becomes us to fulfill all justice.’” There was nothing more to be said or done. Submissively the meek John baptized the meek, submissive Jesus; Jesus had indeed begun at the very beginning. The crowd, already baptized, was threading its way homeward; the few that remained noticed nothing strange; it would seem that what then happened was known alone to John and Jesus. He came up out of the water; for a moment He stood upon the bank absorbed in prayer; while He prayed, with His eyes raised upward, a common attitude as we shall often see: “Lo! He saw the heavens opened to Him and He saw the Spirit of God descending in a bodily shape as a dove and coming and remaining upon Him and behold there came a voice from Heaven saying: ‘This is My beloved Son in Whom I am well pleased! Thou art My beloved Son In Thee I am well pleased.” |

When we read separately the three accounts of the baptism of Jesus, it seems manifest that, to each of the evangelists the chief part of the story the “voice from Heaven” and the witness that it gave. Next it would seem the mere construction of the sentences, more especially the narrative of St. Luke, that the coming of Jesus of His Own accord to be baptized, and the humiliation of baptism, are looked upon as preludes to this; the first public act of self-abasement being followed by the first solemn declaration by the Father, the formal acceptance the Sonship of Man, with all its sin to be atoned for, be rewarded by acknowledgement as the Son of God; true Man, with the consequent burden, true God, with consequent right.