| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

The Greatest and Most Important Time in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS | LITANIES FOR PASSIONTIDE |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | The Last Days of Christ | Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

CLICK ON ANY LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS | LITANIES FOR PASSIONTIDE |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | The Last Days of Christ | Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

WHY DOM GUÉRANGER? WHO IS DOM GUÉRANGER? WHAT IS SOLESMES?

The Liturgical Year (French: L'Année Liturgique) is a written work in fifteen volumes describing the liturgical year of the Catholic Church. The series was written by Dom Prosper Louis Pascal Guéranger, a French Benedictine priest and abbot of Solesmes. Dom Guéranger began writing the work in 1841, and died in 1875 after writing nine volumes. The remaining volumes were completed by another Benedictine under Dom Guéranger's name.

The series describes the liturgy of the Catholic Church throughout the liturgical year, including the Mass and the Divine Office. Also described is the historical development of the liturgy in both Western and Eastern traditions. Biographies of saints and their liturgies are given on their feast days.

The Liturgical Year has been likened to the "Summa Theologica" of St. Thomas Aquinas, which the Council of Trent placed alongside the Bible as a work of authority. Dom Guéranger's "The Liturgical Year" has thus been called the "Summa" of the liturgy of the Catholic Church. However, a word of warning to the reader, just like the :Summa Theologica", you will encounter some dry difficult parts (much like the Israelites in their forty years of penance in the desert), but there will also be found oases of deep spiritual refreshment. Persevere, read slowly, stop to think, and you will draw much fruit from this masterful work. Put away and put aside the modern-man's desire for fast-food, fast-service, being fast-tracked. There is no fast way of getting to Heaven (except for fasting perhaps!!). Besides, I don't think God appreciates being put quickly aside so that we can run off to do what we wrongly imagine to be "better" things. The season that we have entered should see us being more of a Mary than a Martha!

“Now it came to pass as they went, that Jesus entered into a certain town: and a certain woman named Martha, received Him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, who sitting also at the Lord’ s feet, heard his word. But Martha was busy about much serving. Who stood and said: ‘Lord, hast Thou no care that my sister hath left me alone to serve? speak to her therefore, that she help me!’ And the Lord answering, said to her: ‘Martha, Martha, thou art careful, and art troubled about many things: but one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her!’” (Luke 10:38-42).

The series describes the liturgy of the Catholic Church throughout the liturgical year, including the Mass and the Divine Office. Also described is the historical development of the liturgy in both Western and Eastern traditions. Biographies of saints and their liturgies are given on their feast days.

The Liturgical Year has been likened to the "Summa Theologica" of St. Thomas Aquinas, which the Council of Trent placed alongside the Bible as a work of authority. Dom Guéranger's "The Liturgical Year" has thus been called the "Summa" of the liturgy of the Catholic Church. However, a word of warning to the reader, just like the :Summa Theologica", you will encounter some dry difficult parts (much like the Israelites in their forty years of penance in the desert), but there will also be found oases of deep spiritual refreshment. Persevere, read slowly, stop to think, and you will draw much fruit from this masterful work. Put away and put aside the modern-man's desire for fast-food, fast-service, being fast-tracked. There is no fast way of getting to Heaven (except for fasting perhaps!!). Besides, I don't think God appreciates being put quickly aside so that we can run off to do what we wrongly imagine to be "better" things. The season that we have entered should see us being more of a Mary than a Martha!

“Now it came to pass as they went, that Jesus entered into a certain town: and a certain woman named Martha, received Him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, who sitting also at the Lord’ s feet, heard his word. But Martha was busy about much serving. Who stood and said: ‘Lord, hast Thou no care that my sister hath left me alone to serve? speak to her therefore, that she help me!’ And the Lord answering, said to her: ‘Martha, Martha, thou art careful, and art troubled about many things: but one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her!’” (Luke 10:38-42).

|

DOM GUÉRANGER & SOLESMES

Destined to be a Scholar, Priest and Monk, Dom Guéranger would begin his work in the aftermath of the French revolution, when religious life was effectively abolished in all of Europe. Aiming to restore all aspects of monastic life, the preservation of Gregorian chant - the sung liturgy of the church - would be an essential part of Dom Guéranger's goal. He would re-found the Abbey of St. Peter in Solesmes.

Dom Geuranger himself writes: “My youth, the complete lack of temporal resources, and the limited reliability of those with whom I hoped to associate — none of these things stopped me. I would not have dreamed of it; I felt myself pushed to proceed. I prayed with all my heart for the help of God; but it never occurred to me to ask His will concerning the projected work.”

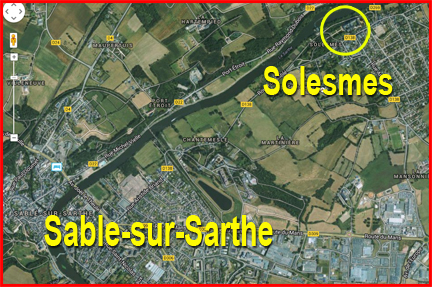

That last statement may surprise us, but Dom Guéranger explains: “The need of the Church seemed to me so urgent, the ideas about true Christianity so falsified and so compromised in the lay and ecclesiastical worlds, that I felt nothing but an urgency to found some kind of center wherein to recollect and revive pure traditions.” Born in Sablé-sur-Sarthe, on April 4, 1805, Prosper Guéranger frequently made Solesmes the destination of his childhood walks, drawn by the charm of the church building and its life-sized saints in stone. Though as a child he never imagined himself a monk, he loved the solitude of the place. Aspiring first to the priesthood, a precocious vocation led him, after his high school studies in Angers, to the seminary in Le Mans. There, he was drawn intensely to the study of Church history, and soon he discovered what the institution of monasticism had been. Contact with the great scholarly works of the Maurists soon awoke in him a real desire for the monastic life.

Ordained a priest in 1827 (Guéranger was only 22 years old at the time, so that his bishop had to obtain a canonical dispensation), he pursued his work as the bishop's secretary in Paris and in Le Mans. In 1831, learning that the priory at Solesmes was destined to destruction for lack of a buyer, the idea came to him to find the means to acquire it and to take up the Benedictine life again. With the help of a few friends and encouraged by his bishop, he gathered together — with considerable difficulty — enough money to rent the monastery property, and subsequently moved in with three companions on July 11, 1833. The fledgling community encountered, of course, difficult times. But its young prior, borne up by his absolute confidence in Providence, by his humility and by his natural mirth and optimism, proved to possess a calm tenacity. Without copying the past in a servile way, he took inspiration from solid monastic traditions pursuing above all the true spirit of St Benedict while accepting several very necessary material adaptations to modern times. As a result, by his uncommon intuition of the benedictine charism, liturgy and spiritual life, he became a living example to his monks. As for temporal matters, Solesmes' first friends saw to the most urgent needs. They inaugurated a second and long list of the monastery's benefactors: the Cosnards, the Landeaus, the Gazeaus, Mme Swetchine, Montalembert, the Marquis of Juigné, and so many others who thought constantly of the monks.

After a four-year tryout Dom Guéranger went to Rome, in 1837, to ask the Vatican for official recognition of Solesmes as a benedictine community. Rome not only granted Dom Guéranger's request, but on its own initiative raised Solesmes from the status of priory to that of an abbey making it the head of a new Benedictine Congregation de France, successor to the Congregations of St. Maurus and St. Vanne as well as the more venerable and ancient family of monasteries belonging to Cluny. On July 26, Dom Guéranger made his solemn profession in the presence of the abbot of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. From then on began a new period in the history of Solesmes. |

THE LITURGICAL LIFE

Extracts from the Commentary on the Daily Liturgy by Dom Prosper Guéranger scroll down for the latest article

Article 1 : ASH WEDNESDAY

"Learn and Live" Dating from the eleventh century, the discipline of public penance began to fall into disuse, and the holy rite of putting ashes on the heads of all the faithful indiscriminately became so general that, at length, it was considered as forming an essential part of the Roman liturgy. Formerly, it was the practice to approach bare-footed to receive this solemn memento of our nothingness; and in the twelfth century, even the Pope himself, when passing from the church of St. Anastasia to that of St. Sabina, at which the station was held, went the whole distance bare-footed, as also did the Cardinals who accompanied him. The Church no longer requires this exterior penance; but she is as anxious as ever that the holy ceremony, at which we are about to assist, should produce in us the sentiments she intended to convey by it, when she first instituted it.

From the liturgy of Ash Wednesday we learn of the prophet Joel and how acceptable to God is the expiation of fasting. When the penitent sinner inflicts corporal penance upon himself, God's justice is appeased. We have a proof of it in the Ninivites. If the Almighty pardoned an infidel city, as Ninive was, solely because its inhabitants sought for mercy under the garb of penance; what will He not do in favor of His own people, who offer Him the twofold sacrifice, exterior works of mortification, and true contrition of heart? Let us, then, courageously enter on the path of penance. We are living in an age when, through want of faith and of fear of God, those practices which are as ancient as Christianity itself, and on which we might almost say it was founded, are falling into disuse; it behoves us to be on our guard, lest we, too, should imbibe the false principles, which have so fearfully weakened the Christian spirit. Let us never forget our own personal debt to the divine justice, which will remit neither our sins nor the punishment due to them, except inasmuch as we are ready to make satisfaction. We have just been told that these bodies, which we are so inclined to pamper, are but dust; and as to our souls, which we are so often tempted to sacrifice by indulging the flesh, they have claims upon the body, claims of both restitution and obedience. In the Gradual, the Church again pours forth the expressions of her confidence in the God of all goodness, for she counts upon her children being faithful to the means she gives them of propitiating His justice. The Tract is that beautiful prayer of the psalmist, which she repeats thrice during each week of Lent, and which she always uses in times of public calamity, in order to appease the angel of God. Our Redeemer would not have us receive the announcement of the great fast as one of sadness and melancholy. The Christian who understands what a dangerous thing it is to be behindhand with divine justice, welcomes the season of Lent with joy; it consoles him. He knows that if he be faithful in observing what the Church prescribes, his debt will be less heavy upon him. These penances, these satisfactions (which the indulgence of the Church has rendered so easy), being offered to God unitedly with those of our Savior Himself, and being rendered fruitful by that holy fellowship which blends into one common propitiatory sacrifice the good works of all the members of the Church militant, will purify our souls, and make them worthy to partake in the grand Easter joy. Let us not, then, be sad because we are to fast; let us be sad only because we have sinned and made fasting a necessity. In this same Gospel, our Redeemer gives us a second counsel, which the Church will often bring before us during the whole course of Lent: it is that of joining almsdeeds with our fasting. He bids us to lay up treasures in Heaven. For this, we need intercessors; let us seek them amidst the poor. Article 2

THE MYSTERY OF THE FORTY DAYS We may be sure, that a season, so sacred as this of Lent, is rich in mysteries. The Church has made it a time of recollection and penance, in preparation for the greatest of all her Feasts; she would, therefore, bring into it everything that could excite the faith of her children, and encourage them to go through the arduous work of atonement for their sins. During Septuagesima, we had the number―“Seventy”―which reminded us of those seventy years’ captivity in Babylon, after which, God’s chosen people, being purified from idolatry, was to return to Jerusalem and celebrate the Pasch. It is the number Forty that the Church now brings before us―a number, as Saint Jerome observes, which denotes punishment and affliction (Commentary on Ezechiel, chapter 29).

Let us remember the forty days and forty nights of the Deluge (Genesis 7:12), sent by God in His anger, when He repented that he had made man, and destroyed the whole human race, with the exception of one family. Let us consider how the Hebrew people, in punishment for their ingratitude, wandered forty years in the desert, before they were permitted to enter the Promised Land (Numbers 14:33). Let us listen to our God commanding the Prophet Ezechiel to be forty days on His right side, as a figure of the siege, which was to bring destruction on Jerusalem (Ezechiel 4:6). There are two, in the Old Testament, who represent, in their own persons, the two manifestations of God: Moses, who typifies the Law; and Elias, who is the figure of the Prophets. Both of these are permitted to approach God―the first on Sinai (Exodus 24:18), the second on Horeb (3 Kings 19:8)―but both of them have to prepare for the great favor by an expiatory fast of forty days. With these mysterious facts before us, we can understand why it was, that the Son of God, having become Man for our salvation, and wishing to subject himself to the pain of fasting, chose the number of Forty Days. The institution of Lent is thus brought before us with everything that can impress the mind with its solemn character, and with its power of appeasing God and purifying our souls. Let us, therefore, look beyond the little world which surrounds us, and see how the whole Christian universe is, at this very time, offering this Forty Days’ penance as a sacrifice of propitiation to the offended Majesty of God; and let us hope, that, as in the case of the Ninivites, He will mercifully accept this year’s offering of our atonement, and pardon us our sins. The number of our days of Lent is, then, a holy mystery: let us, now, learn from the Liturgy, in what light the Church views her Children during these Forty Days. She considers them as an immense army, fighting, day and night, against their Spiritual enemies. We remember how, on Ash Wednesday, she calls Lent a Christian Warefare. Yes―in order that we may have that newness of life, which will make us worthy to sing once more our Alleluia―we must conquer our three enemies the devil, the flesh, and the world. We are fellow combatants with our Jesus, for He, too, submits to the triple temptation, suggested to him by Satan in person. Therefore, we must have on our armor, and watch unceasingly. And whereas it is of the utmost importance that our hearts be spirited and brave, the Church gives us a war-song of heaven’s own making, which can fire even cowards with hope of victory and confidence in God’s help: it is the Ninetieth Psalm (Psalm Qui habitat in adjutorio altissimi, in the Office of Compline for Thursdays). She inserts the whole of it in the Mass of the First Sunday of Lent, and, every day, introduces several of its verses in the Ferial Office. She there tells us to rely on the protection, wherewith our Heavenly Father covers us, as with a shield (Scuto circumdabit to veritas ejus, the Responsory during ferial days of Lent at None and the Office of Compline for Sundays]; to hope under the shelter of His wings (Et sub pennis ejus sperabis, the Responsory during ferial days of Lent at Sext and Sunday Compline); to have confidence in Him, for that He will deliver us from the snare of the hunter (Ipse liberavit me de laqueo venantium, the Responsory during ferial days of Lent at Tierce and Sunday Compline), who had robbed us of the holy liberty of the children of God; to rely upon the help of the Holy Angels, who are our Brothers, to whom our Lord hath given charge that they keep us in all our ways (Angelis suis mandavit de te, ut custodiant te in omnibus viis tuis, versicle during ferial days of Lent at Lauds and Vespers and Sunday Compline), and who, when our Jesus permitted Satan to tempt Him, were the adoring witnesses of His combat, and approached Him, after His victory, proffering to Him their service and homage. Let us get well into us these sentiments wherewith the Church would have us be inspired; and, during our six weeks’ campaign, let us often repeat this admirable Canticle, which so fully describes what the Soldiers of Christ should be and feel in this season of the great spiritual warfare. Article 3

THREE GREAT SUBJECTS TO PONDER The Church is not satisfied with thus animating us to the contest with our enemies―she would also have our minds engrossed with thoughts of deepest importance; and for this end, she puts before us three great subjects, which she will gradually unfold to us between this and the great Easter Solemnity. Let us be all attention to these soul-stirring and instructive lessons.

FIRSTLY, there is the conspiracy of the Jews against our Redeemer. It will be brought before us in its whole history, from its first formation to its final consummation on the great Friday, when we shall behold the Son of God hanging on the Wood of the Cross. The infamous workings of the synagogue will be brought before us so regularly, that we shall be able to follow the plot in all its details. We shall be inflamed with love for the august Victim, whose meekness, wisdom, and dignity, bespeak a God. The divine drama, which began in the cave of Bethlehem, is to close on Calvary; we may assist at it, by meditating on the passages of the Gospel read to us, by the Church, during these days of Lent. The SECOND of the subjects offered to us, for our instruction, requires that we should remember how the Feast of Easter is to be the day of new birth for our Catechumens; and how, in the early ages of the Church, Lent was the immediate and solemn preparation given to the candidates for Baptism. The holy Liturgy of the present season retains much of the instruction she used to give to the Catechumens; and as we listen to her magnificent Lessons from both the Old and the New Testament, whereby she completed their initiation, we ought to think with gratitude on how we were not required to wait years before being made Children of God, but were mercifully admitted to Baptism, even in our Infancy. We shall be led to pray for those new Catechumens, who this very year, in far distant countries, are receiving instructions from their zealous Missioners, and are looking forward, as did the postulants of the primitive Church, to that grand Feast of our Saviour’s victory over Death, when they are to be cleansed in the Waters of Baptism and receive from the contact a flew being, - regeneration. THIRDLY, we must remember how, formerly, the public Penitents, who had been separated, on Ash Wednesday, from the assembly of the Faithful, were the object of the Church’s maternal solicitude during the whole Forty Days of Lent, and were to be admitted to Reconciliation on Maundy Thursday, if their repentance were such as to merit this public forgiveness. We shall have the admirable course of instructions, which were originally designed for these Penitents, and which the Liturgy, faithful as she ever is to such traditions, still retains for our sakes. As we read these sublime passages of the Scripture, we shall naturally think upon our own sins, and on what easy terms they were pardoned us; whereas, had we lived in other times, we should have probably been put through the ordeal of a public and severe penance. This will excite us to fervor, for we shall remember, that, whatever changes the indulgence of the Church may lead her to make in her discipline, the justice of our God is ever the same. We shall find in all this an additional motive for offering to his Divine Majesty the sacrifice of a contrite heart, and we shall go through our penances with that cheerful eagerness, which the conviction of our deserving much severer ones always brings with it. Article 4

HISTORY OF PASSIONTIDE AND HOLY WEEK After having proposed the forty-days’ fast of Jesus in the desert to the meditation of the faithful during the first four weeks of Lent, the holy Church gives the two weeks which still remain before Easter to the commemoration of the Passion. She would not have her children come to that great day of the immolation of the Lamb, without having prepared for it by compassionating with Him in the sufferings He endured in their stead.

The most ancient sacramentaries and antiphonaries of the several Churches attest, by the prayers, the lessons, and the whole liturgy of these two weeks, that the Passion of Our Lord is now the one sole thought of the Christian world. During Passion-week, a saint’s feast, if it occur, will be kept; but Passion Sunday admits no feast, however solemn it may be; and even on those which are kept during the days intervening between Passion and Palm Sunday, there is always made a commemoration of the Passion, and the holy images are not allowed to be uncovered. We cannot give any historical details upon the first of these two weeks; its ceremonies and rites have always been the same as those of the four preceding ones. We, therefore, refer the reader to the following chapter, in which we treat of the mysteries peculiar to Passiontide. The second week, on the contrary, furnishes us with abundant historical details; for there is no portion of the liturgical year which has interested the Christian world so much as this, or which has given rise to such fervent manifestations of piety. This week was held in great veneration even as early in the third century, as we learn from St. Denis, Bishop of Alexandria, who lived at that time. In the following century, we find St. John Chrysostom, calling it the great week: ‘Not,’ says the holy doctor, ‘that it has more days in it than other weeks, or that its days are made up of more hours than other days; but we call it great, because of the great mysteries which are then celebrated.’ We find it called also by other names: the “painful week” (hebdomada poenosa), on account of the sufferings of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and of the fatigue required from us in celebrating them; the week of indulgence, because sinners are then received to penance; and, lastly, “Holy Week”, in allusion to the holiness of the mysteries which are commemorated during these seven days. This last name is the one under which it most generally goes with us; and the very days themselves are, in many countries, called by the same name, Holy Monday, Holy Tuesday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday. The severity of the Lenten fast is increased during these its las days; the whole energy of the spirit of penance is now brought out. Even with us, the dispensation which allows the use of eggs ceases towards the middle of this week. The eastern Churches, faithful to their ancient traditions, have kept up a most rigorous abstinence ever since the Monday of Quinquagesima week. During the whole of this long period, which they call Xerophagia, they have been allowed nothing but dry food. In the early ages, fasting during Holy Week was carried to the utmost limits that human nature could endure. We learn from St. Epiphanius, that there were some of the Christians who observed a strict fast from Monday morning to cock-crow of Easter Sunday. Of course it must have been very few of the faithful who could go so far as this. Many passed two, three, and even four consecutive days, without tasting any food; but the general practice was to fast from Maundy Thursday evening to Easter morning. Many Christians in the east, and in Russia, observe this fast even in these times. Would that such severe penance were always accompanied by a firm Faith and union with the Church, out of which the merit of such penitential works is of no avail for salvation! Another of the ancient practices of Holy Week, were the long hours spent, during the night, in the churches. On Maundy Thursday, after having celebrated the divine mysteries in remembrance of the Last Supper, the faithful continued a long time in prayer. The night between Friday and Saturday was spent in almost uninterrupted vigil, in honor of Our Lord's burial. But the longest of all these vigils was that of Saturday, which was kept up till Easter Sunday morning. The whole congregation joined in it: they assisted at the final preparation of the catechumens, as also at the administration of Baptism; nor did they leave the church until after the celebration of the holy Sacrifice, which was not over till sunrise. Cessation from servile work was, for a long time, an obligation during Holy Week. The civil law united with that of the Church in order to bring about this solemn rest from toil and business, which so eloquently expresses the state of mourning of the Christian world. The thought of the sufferings and death of Jesus was the one pervading thought: the Divine Offices and prayer were the sole occupation of the people: and, indeed, all the strength of the body was needed for the support of the austerities of fasting and abstinence. We can readily understand what an impression was made upon men's minds, during the whole of the rest of the year, by this universal suspension of the ordinary routine of life. Moreover, when we call to mind how, for five full weeks, the severity of Lent had waged war on the sensual appetites, we can imagine the simple and honest joy wherewith was welcomed the feast of Easter, which brought both the regeneration of the soul, and respite to the body. Article 5

THE MERCIES OF PASSIONTIDE AND HOLY WEEK In the preceding volume, we mentioned the laws of the Theodosian Code, which forbade all law business during the forty days preceding Easter. This law of Gratian and Theodosius, which was published in 380, was extended by Theodosius in 389, this new decree forbade all pleadings during the seven days before, and the seven days after, Easter. We meet with several allusions to this then recent law, in the homilies of St. John Chrysostom, and in the sermons of St. Augustine. In virtue of this decree, each of these fifteen days was considered, as far as the courts of law were concerned, as a Sunday.

But Christian princes were not satisfied with the mere suspension of human justice during these days, which are so emphatically days of mercy: they would, moreover, pay homage, by an external act, to the fatherly goodness of God, who has deigned to pardon a guilty world, through the merits of the death of His Son. The Church was on the point of giving reconciliation to repentant sinners, who had broken the chains of sin whereby they were held captives; Christian princes were ambitious to imitate this their mother, and they ordered that prisoners should be loosened from their chains, that the prisons should be thrown open, and that freedom should be restored to those who had fallen under the sentence of human tribunals. The only exception made was that of criminals whose freedom would have exposed their families or society to great danger. The name of Theodosius stands prominent in these acts of mercy. We are told by St John Chrysostom that this emperor sent letters of pardon to the several cities, ordering the release of prisoners, and granting life to those that had been condemned to death, and all this in order to sanctify the days preceding the Easter feast. The last emperors made a law of this custom, as we find in one of Pope St. Leo the Great’s sermons, where he thus speaks of their clemency: “The Roman emperors have long observed this holy practice. In honor of Our Lord's Passion and Resurrection, they humbly withhold the exercise of their sovereign justice, and, laying aside the severity of their laws, they grant pardon to a great number of criminals. Their intention in this is to imitate the divine goodness by their own exercise of clemency during these days, when the world owes its salvation to the divine mercy. Let, then, the Christian people imitate their princes, and let the example of kings induce subjects to forgive each other their private wrongs; for, surely it is absurd that private laws should be less unrelenting than those which are public. Let trespasses be forgiven, let bonds be taken-off, let offences be forgotten, let revenge be stifled; that thus the sacred feast may, by both divine and human favors, find us all happy and innocent.” This Christian amnesty was not confined to the Theodosian Code; we find traces of it in the laws of several of our western countries. We may mention France as an example. Under the first race of its kings, St. Eligius Bishop of Noyon, in a sermon for Maundy Thursday, thus expresses himself: “On this day, when the Church grants indulgence to penitents and absolution to sinners, magistrates, also, relent in their severity and grant pardon to the guilty. Throughout the whole world prisons are thrown open; princes show clemency to criminals, masters forgive their slaves.” Under the second race, we learn from the “Capitularia of Charlemagne”, that bishops had a right to exact from the judges, for the love of Jesus Christ (as it is expressed), that prisoners should be set free on the days preceding Easter; and should the magistrates refuse to obey, the bishops could refuse them admission into the church. And, lastly, under the third race, we find Charles VI, after quelling the rebellion at Rouen, giving orders, later on, that the prisoners should be set at liberty, because it was “Painful Week”, and very near to the Easter feast. A last vestige of this merciful legislation was a custom observed by the parliament of Paris. The ancient Christian practice of suspending its sessions during the whole of Lent, had long been abolished: it was not till the Wednesday of Holy Week that the house was closed, which it continued to be from that day until after Low Sunday. On the Tuesday of Holy Week, which was the last day granted for audiences, the parliament repaired to the palace prisons, and there one of the grana presidents, generally the last installed, held a session of the house. The prisoners were questioned; but, without any formal judgment, all those whose case seemed favorable, or who were not guilty of some capital offence, were set at liberty. Article 6

WE ARE LOSING IT OR HAVE ALREADY LOST IT! The revolutions of the last eighty-years have produced in every country in Europe the secularization of society, that is to say, the effacing from our national customs and legislation of everything which had been introduced by the supernatural element of Christianity. The favorite theory of the last half-century or more, has been that all men are equal.

The people of the ages of Faith had something far more convincing than theory, of the sacredness of their rights. At the approach of those solemn anniversaries which so forcibly remind us of the justice and mercy of God, they beheld princes abdicating, as it were, their scepter, leaving in God's hands the punishment of the guilty, and assisting at the holy Table of Paschal Communion side by side with those very men, whom, a few days before, they had been keeping chained in prison for the good of society. There was one thought, which, during these days, was strongly brought before all nations: it was the thought of God, in Whose eyes all men are sinners; of God, from Whom alone proceed justice and pardon. It was in consequence of this deep Christian feeling, that we find so many diplomas and charters of the ages of Faith speaking of the days of Holy Week as being the reign of Christ: such an event, they say, happened on such a day, under the reign of Our Lord Jesus Ohrist: regnante Domino nostro Jesu Christo. When these days of holy and Christian equality were over, did subjects refuse submission to their sovereign? Did they abuse the humility of their princes, and take occasion for drawing up what modern times call the rights of man? No! That same thought which had inspired human justice to humble itself before the cross of Jesus, taught the people their duty of obeying the powers established by God. The exercise of power, and submission to that power, both had God for their motive. They who wielded the scepter might be of various dynasties: the respect for authority was ever the same. Nowadays, the liturgy has none of her ancient influence on society; religion has been driven from the world at large, and her only life and power is now with the consciences of individuals; and as to political institutions, they are but the expression of human pride, seeking to command, or refusing to obey. And yet the fourth century, which, in virtue of the Christian spirit, produced the laws we have been alluding to, was still rife with the pagan element. How comes it that we, who live in the full light of Christianity, can give the name of progress to a system which tends to separate society from everything that is supernatural? Men may talk as they please, there is but one way to secure order, peace, morality, and security to the world; and that is God's war, the war of Faith, of living in accordance with the teachings and the spirit of Faith. All other systems can, at best, but flatter those human passions, which are so strongly at variance with the mysteries of Our Lord Jesus Christ, which we are now celebrating. We must mention another law made by the Christian emperors in reference to Holy Week. If the spirit of charity, and a desire to imitate divine mercy, led them to decree the liberation of prisoners; it was but acting consistently with these principles, that, during these days when our Savior shed His Blood for the emancipation of the human race, they should interest themselves in what regards slaves. Slavery, a consequence of sin, and the fundamental institution of the pagan world, had received its death-blow by the preaching of the Gospel; but its gradual abolition was left to individuals, and to their practical exercise of the principle of Christian fraternity. As Our Lord and His Apostles had not exacted the immediate abolition of slavery, so, in like manner, the Christian emperors limited themselves to passing such laws as would give encouragement to its gradual abolition. We have an example of this in the Justinian Code, where this prince, after having forbidden all law-proceedings during Holy Week and the week following, lays down the following exception: “It shall, nevertheless, be permitted to give slaves their liberty; in such manner, that the legal arts necessary for their emancipation shall not be counted as contravening this present enactment.” This charitable law of Justinian was but applying to the fifteen days of Easter the decree passed by Constantine, which forbade all legal proceedings on the Sundays throughout the year, excepting only such acts as had for their object the emancipation of slaves. But long before the peace given her by Constantine, the Church had made provision for slaves, during these days when the mysteries of the world's redemption were accomplished. Christian masters were obliged to grant them total rest from labor during this holy fortnight. Such is the law laid down in the apostolic constitutions, which were compiled previously to the fourth century. “During the Great Week preceding the day of Easter, and during the week that follows, slaves rest from labor, inasmuch as the first is the week of Our Lord's Passion, and the second is that of His Resurrection; and the slaves require to be instructed upon these mysteries.” Another characteristic of the two weeks, upon which we are now entering, is that of giving more abundant alms, and of greater fervor in the exercise of works of mercy. St. John Chrysostom assures us that such was the practice of his times; he passes an encomium on the faithful, many of whom redoubled, at this period, their charities to the poor, which they did out of this motive: that they might, in some slight measure, imitate the divine generosity, which is now so unreservedly pouring out its graces on sinners. Article 7

THE PRACTICES OF PASSIONTIDE AND HOLY WEEK (Part 1) The past four weeks seems to have been but a preparation for the intense grief of the Church during these two. She knows that men are in search of her Jesus, and that they are bent on His death. Before twelve days are over, she will see them lay their sacrilegious hands upon Him. She will have to follow Him up the hill of Calvary; she will have to receive His last breath; she must witness the stone placed against the sepulcher where His lifeless Body is laid. We cannot, therefore, be surprised at her inviting all her children to contemplate, during these weeks, Him who is the object of all her love and all her sadness.

But our mother asks something more of us than compassion and tears; she would have us profit by the lessons we are to be taught by the Passion and Death of our Redeemer. He himself, when going up to Calvary, said to the holy women who had the courage to show their compassion even before His very executioners: “Weep not over Me; but weep for yourselves and for your children!” (St. Luke 23:28). It was not that He refused the tribute of their tears, for He was pleased with this proof of their affection; but it was His love for them that made him speak thus. He desired, above all, to see them appreciate the importance of what they were witnessing, and learn from it how in exorable is God’s justice against sin. During the four weeks that have preceded, the Church has been leading the sinner to his conversion; so far, however, this conversion has been but begun: now she would perfect it. It is no longer our Jesus fasting and praying in the desert, that she offers to our consideration; it is this same Jesus, as the great Victim immolated for the world’s salvation. The fatal hour is at hand; the power of darkness is preparing to make use of the time that is still left; the greatest of crimes is about to be perpetrated. A few days hence the Son of God is to be in the hands of sinners, and they will put Him to death. The Church no longer needs to urge her children to repentance; they know too well, now, what sin must be, when it could require such expiation as this. She is all absorbed in the thought of the terrible event, which is to close the life of the God-Man on Earth; and by expressing her thoughts through the holy liturgy, she teaches us what our own sentiments should be. The pervading character of the prayers and rites of these two weeks, is a profound grief at seeing the just One persecuted by His enemies even to death, and an energetic indignation against the deicides. The formulas, expressive of these two feelings are, for the most part, taken from David and the Prophets. Here, it is our Savior Himself, disclosing to us the anguish of His soul; there, it is the Church pronouncing the most terrible anathemas upon the executioners of Jesus. The chastisement that is to befall the Jewish nation is prophesied in all its frightful details; and on the last three days, we shall hear the prophet Jeremias uttering his lamentations over the faithless city. The Church does not aim at exciting idle sentiment; what she principally seeks, is to impress the hearts of her children with a salutary fear. If Jerusalem’s crime strike them with horror, and if they feel that they have partaken in her sin, their tears will flow in abundance. Let us, therefore, do our utmost to receive these strong impressions, too little known, alas! by the superficial piety of these times. Let us reflect upon the love and affection of the Son of God, who has treated His creatures with such unlimited confidence, lived their own life, spent His three and thirty years amidst them, not only humbly and peaceably, but in going about doing good (Acts 1:38). And now this life of kindness, condescension, and humility, is to be cut short by the disgraceful death, which none but slaves endured: the death of the cross. Let us consider, on the one side, this sinful people, who, having no crimes to lay to Jesus’ charge, accuse Him of his benefits, and carry their detestable ingratitude to such a pitch as to shed the Blood of this innocent and divine Lamb; and then, let us turn to this Jesus, the Just by excellence, and see Him become a prey to every bitterest suffering: His Soul sorrowful even unto death (Matthew 26:38); weighed down by the malediction of our sins; drinking even to the very dregs the chalice He so humbly asks His Father to take from Him; and lastly, let us listen to His dying words: “My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken Me?” (Matthew 27:46). This it is that fills the Church with her immense grief; this it is that she proposes to our consideration; for she knows that, if we once rightly understood the sufferings of her Jesus, our attachments to sin must needs be broken, for, by sin, we make our selves guilty of the crime we detest in these Jews. But the Church knows, too, how hard is the heart of man, and how, to make him resolve on a thorough Conversion, he must be made to fear. For this reason, she puts before us those awful imprecations, which the prophets, speaking in Jesus’ person, pronounced against them that put our Lord to death. These prophetic anathemas were literally fulfilled against the obdurate Jews. They teach us what the Christian, also, must expect, if, as the Apostle so forcibly expresses it, we again crucify the Son of God (Hebrews 6:6). In listening to what the Church now speaks to us, we cannot but tremble as we recall to mind those other words of the same Apostle: How much more, think ye, doth he deserve worse punishment, who hath trodden underfoot the Son of God, and hath esteemed the Blood of the testament unclean, (as though it were some vile thing), by which he was sanctified, and hath offered an affront to the Spirit of grace? For we know Him that hath said: “Vengeance belongeth to Me, and I will repay.” And again: “The Lord shall judge His people.” “It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God” (Hebrews 10:29-31). Fearful indeed it is! O what a lesson God gives us of His inexorable justice, during these days of the Passion! He that spared not even his own Son (Romans 8:32), His beloved Son, in whom He is well pleased (Matthew 3:17), will He spare us, if, after all the graces He has bestowed upon us, He should find us in sin, which He so unpitifully chastised even in Jesus, when He took it upon himself, that He might atone for it? Considerations such as these ― the justice of God towards the most innocent and august of victims, and the punishments that befell the impenitent Jews ― must surely destroy within us every affection to sin, for they will create within us that salutary fear which is the solid foundation of firm hope and tender love. For if, by our sins, we have made ourselves guilty of the death of the Son of God, it is equally true that the Blood which flowed from His sacred wounds has the power to cleanse us from the guilt of our crime. The justice of our Heavenly Father cannot be appeased, save by the shedding of this precious Blood; and the mercy of this same Father wills that it be spent for our ransom. The cruelty of Jesus’ executioners has made five wounds in His sacred Body; and from these, there flow five sources of salvation, which purify the world, and restore within each one of us the image of God which sin had destroyed. Let us, then, approach with confidence to this redeeming Blood, which throws open to the sinner the gates of Heaven, and whose worth is such that it could redeem a million worlds, were they even more guilty than ours. We are close upon the anniversary of the day when it was shed; long ages have passed away since it flowed down the wounded Body of our Jesus, and fell in streams from the cross upon this ungrateful Earth; and yet its power is as great as ever. Let us go, then, and draw from the Savior’s fountains (Isaias 12:3); our souls will come forth full of life, all pure, and dazzling with Heavenly beauty; not one spot of their old defilements will be left; and the Father will love us with the love wherewith He loves His own Son. Why did He deliver up unto death this His tenderly beloved Son? Was it not that He might regain us, the children whom He had lost? We had become, by our sins, the possession of Satan; Hell had undoubted claims upon us; and, lo, we have been suddenly snatched from both, and all our primitive rights have been restored to us. Yet God used no violence in order to deliver us from our enemy; how comes it, then, that we are now free? Listen to the Apostle: “Ye are bought at a great price” (1 Corinthians 6:20). And what is this price? The prince of the Apostles explains it: “Know ye,” says he, “that ye were not redeemed with corruptible things, as gold or silver, but with the precious Blood of Christ as of a Lamb unspotted and undefiled” (1 Peter 1:18-19). This divine Blood was placed in the scales of God’s justice, and so far did it outweigh our iniquities, as to make the bias in our favor. The power of this Blood has broken the very gates of Hell, severed our chains, and made peace both as to the things on Earth, and the things that are in Heaven (Colossians 1:20). Let us receive upon us, therefore, this precious Blood, wash our wounds in it, and sign our foreheads with it as with an indelible mark, which may protect us, on the day of wrath, from the sword of vengeance. Article 8

THE PRACTICES OF PASSIONTIDE AND HOLY WEEK (Part 2) There is another object most dear to the Church, which she, during these two weeks, recommends to our deepest veneration; it is the cross, the altar upon which our incomparable Victim is immolated. Twice during the course of the year, that is, on the feasts of its Invention and Exaltation, this sacred Wood will be offered to us that we may honor it as the trophy of our Jesus’ victory; but now, it speaks to us but of His sufferings, it brings with it no other idea but that of His humiliation. God had said in the ancient Covenant: “Accursed is he that hangeth on a tree” (Deuteronomy 21:23). The Lamb, that saved us, disdained not to suffer this curse; but, for that very cause, this tree, this wood of infamy, has become dear to us beyond measure. It is the instrument of our salvation, it is the sublime pledge of Jesus’ love for us. On this account, the Church is about to lavish her veneration and love upon it; and we intend to imitate her, and join her in this, as in all else she does. An adoring gratitude towards the Blood that has redeemed us, and a loving veneration of the holy cross ― these are the two sentiments which are to be uppermost in our hearts during these two weeks.

But for the Lamb Himself ― for Him that gave us this Blood, and so generously embraced the cross that saved us ― what shall we do? Is it not just that we should keep close to Him, and that, more faithful than the Apostles who abandoned Him during His Passion, we should follow Him day by day, nay, hour by hour, in the way of the cross that He treads for us? Yes, we will be His faithful companions during these last days of His mortal life, when He submits to the humiliation of having to hide Himself from His enemies. We will envy the lot of those devoted few, who shelter Him in their houses, and expose themselves, by this courageous hospitality, to the rage of His enemies. We will compassionate His Mother, who suffered an anguish that no other heart could feel, because no other creature could love Him as she did. We will go, in spirit, into that most hated Sanhedrim, where they are laying the impious plot against the life of the just One. Suddenly, we shall see a bright speck gleaming on the dark horizon; the streets and squares of Jerusalem will re-echo with the cry of Hosanna to the Son of David. That unexpected homage paid to our Jesus, those palm branches, those shrill voices of admiring Hebrew children, will give a momentary truce to our sad forebodings. Our love shall make us take part in the loyal tribute thus paid to the King of Israel, who comes so meekly to visit the daughter of Sion, as the prophet had foretold He would: but, alas, this joy will be short-lived, and we must speedily relapse into our deep sorrow of soul! The traitorous disciple will soon strike his bargain with the high priests; the last Pasch will be kept, and we shall see the figurative lamb give place to the true one, whose Flesh will become our food, and His Blood our drink. It will be our Lord’s Supper. Clad in the nuptial robe, we will take our place there, together with the disciples; for that day is the day of reconciliation, which brings together, to the same holy Table, both the penitent sinner, and the just that has been ever faithful. Then, we shall have to turn our steps towards the fatal garden, where we shall learn what sin is, for we shall behold our Jesus agonizing beneath its weight, and asking some respite from His eternal Father. Then, in the dark hour of midnight, the servants of the high priests and the soldiers, led on by the vile Iscariot, will lay their impious hands on the Son of God; and yet the legions of angels, who adore Him, will be withheld from punishing the awful sacrilege! After this, we shall have to repair to the various tribunals, whither Jesus is led, and witness the triumph of injustice. The time that elapses between his being seized in the garden and His having to carry His cross up the hill of Calvary, will be filled up with the incidents of His mock trial ― lies, calumnies, the wretched cowardice of the Roman governor, the insults of the by-standers, and the cries of the ungrateful populace thirsting for innocent Blood! We shall be present at all these things; our love will not permit us to separate ourselves from that dear Redeemer, who is to suffer them for our sake, for our salvation. Finally, after seeing Him struck and spit upon, and after the cruel scourging and the frightful insult of the crown of thorns, we will follow our Jesus up Mount Calvary; we shall know where His sacred feet have trod by the Blood that marks the road. We shall have to make our way through the crowd, and, as we pass, we shall hear terrible imprecations uttered against our divine Master. Having reached the place of execution, we shall behold this august Victim stripped of His garment, nailed to the cross, hoisted into the air, as if the better to expose Him to insult! We will draw near to the free of life, that we may lose neither one drop of that Blood which flows for the cleansing of the world, nor one single word spoken, for its instruction, by our dying Jesus. We will compassionate His Mother, whose heart is pierced through with a sword of sorrow; we will stand close to her, when her Son, a few moments before His death, shall consign us to her fond care. After His three hours’ agony, we will reverently watch His sacred Head bow down, and receive, with adoring love, His last breath. A bruised and mangled corpse, stiffened by the cold of death – this is all that remains to us of that Son of Man, whose first coming into the world caused us such joy! The Son of the eternal Father was not satisfied with emptying Himself and taking the form of a servant (Philippians 2:7); this His being born in the flesh was but the beginning of His sacrifice; His love was to lead Him even unto death, even to the death of the cross. He foresaw that He would not win our love save at the price of such a generous immolation, and His heart hesitated not to make it. ‘Let us, therefore, love God,’ says St. John, “because God first loved us” (1 John 4:19). This is the end the Church proposes to herself by the celebration of these solemn anniversaries. After humbling our pride and our resistance to grace by showing us how Divine Justice treats sin, she leads our hearts to love Jesus, Who delivered Himself up, in our stead, to the rigors of that justice. Woe to us, if this great week fail to produce in our souls a just return towards Him who loved us more than Himself, though we were, and had made ourselves, His enemies. Let us say with the Apostle: “The charity of Christ presseth us; that they who live, may not now live to themselves, but unto Him who died for them” (2 Corinthians 5:14-15). We owe this return to Him who made Himself a Victim for our sake, and who, up to the very last moment, instead of pronouncing against us the curse we so justly deserved, prayed and obtained for us mercy and grace. He is, one day, to reappear on the clouds of Heaven, and as the prophet says, men shall look upon Him whom they have pierced (Zacharias 3:10). God grant that we may be of the number of those who, having made amends by their love for the crimes they have committed against the divine Lamb, will then find confidence at the sight of those wounds! Let us hope that, by God’s mercy, the holy time we are now entering upon will work such a happy change in us, that, on the day of judgment, we may confidently fix our eyes on Him we are now about to contemplate crucified by the hands of sinners. The death of Jesus puts the whole of nature in commotion; the midday sun is darkened, the Earth is shaken to its very foundations, the rocks are split: may it be that our hearts, too, be moved, and pass from indifference to fear, from fear to hope, and, at length, from hope to love; so that, having gone down, with our Crucified, to the very depths of sorrow, we may deserve to rise again with Him unto light and joy, beaming with the brightness of His Resurrection, and having within ourselves the pledge of a new life, which shall then die no more! Article 9

THE MEANING AND SYMBOLISM OF PALM SUNDAY Early in the morning of this day, Jesus sets out for Jerusalem, leaving Mary His Mother, and the two sisters Martha and Mary Magdalene, and Lazarus, at Bethania. The Mother of sorrows trembles at seeing her Son thus expose Himself to danger, for His enemies are bent upon His destruction; but it is not death, it is triumph, that Jesus is to receive today in Jerusalem. The Messias, before being nailed to the cross, is to be proclaimed King by the people of the great city; the little children are to make her streets echo with their Hosannas to the Son of David; and this in presence of the soldiers of Rome’s emperor, and of the high priests and Pharisees: the first standing under the banner of their eagles; the second, dumb with rage.