| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CHOOSE THE MIRACLE YOU WISH TO READ ABOUT FROM THE LINKS BELOW

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

THE VICTORY OF THE HOLY ROSARY AT LEPANTO

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

PART FOUR

READY FOR BATTLE

A Weakened Catholic Europe Prepares To Defend Itself

READY FOR BATTLE

A Weakened Catholic Europe Prepares To Defend Itself

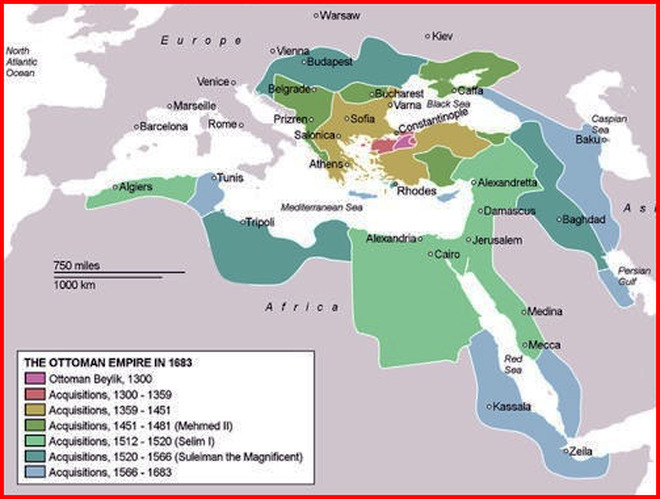

Below, you can see the threat that the Ottoman Empire posed to Europe, with its crab's pincer-like expansion on both the northern and southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. A gradual, persistent, relentless advancing Islamic Empire, making more and more inroads into the lands that surrounded it. With each century the Ottoman Empire would erode more and more off the continent of Europe and that of North Africa. Rarely were they ever beaten in battle, it seemed as though they were invincible and that Europe would eventually and inevitably fall to their domination.

|

TO FIGHT OR NOT TO FIGHT

There comes a point with noisy and aggressive neighbors, when toleration and biting one's lip has gone past its limits. Yet, it is always the first step that is always the hardest.

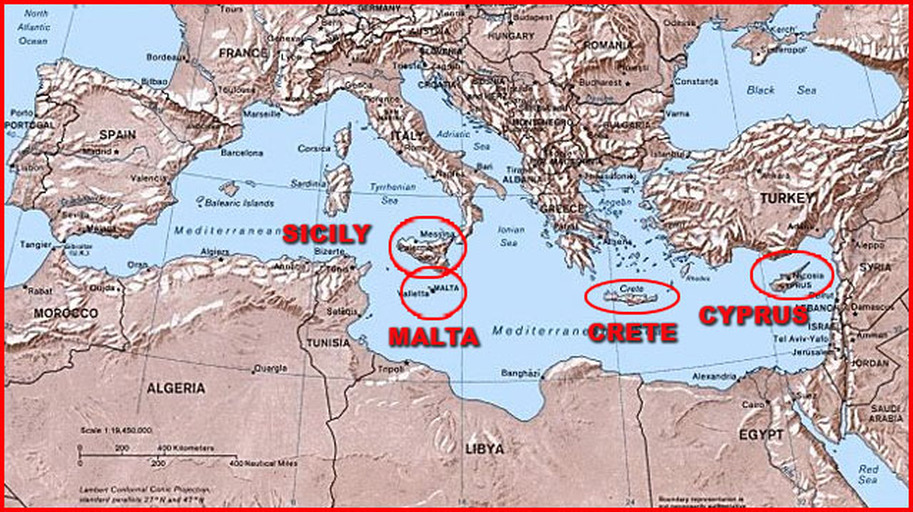

The Islamic Ottoman Empire neighbor of Europe had long since crossed the boundaries of the 'fence' that separated the now Islamic Middle East from Christian Europe. As the map alongside shows, the Ottoman neighbors had been invading more and more of the 'garden' of Europe as the centuries went by 250 years of 'trespassing' on European soil had not satisfied the Ottoman greed for annexing more and more of the European garden. In fact, their eye was fixed on Europe's religious and cultural center—Rome, which they called the "Red Apple" and by the mid-16th century, they were pretty close to picking that apple. The gardeners of Europe were not doing their job, and most were preoccupied with self-interest and self-aggrandizement. The monarchs of England and dissident Catholics (Anglicans who had rebelled against the Papacy) were busy filling their coffers with confiscated Church property. Germany was likewise snapping up and grabbing Church property and rebelling against Rome. France was succumbing to the influence of the Protestant Huguenots, and they even had a trade agreement with the Ottoman Turks, whose navy was harbored in French ports. The State of Venice, being a center of sea traders, were also trading with the Ottoman Turks. For them the "ker-ching! ker-ching!" of the cash register was more important than protecting the Faith and people from the marauding, pillaging, torturing, murdering, raping Turks. The Turkish invaders with their atrocities, and the loss of territory, could be tolerated as long as the money kept coming in from the trade. The Holy Roman Empire (see middle map alongside) was not so "Holy" anymore and was greatly reduced in its political, religious and moral power. Suspicions, intrigues, jealousies, envy, greed and brooding dislike of one European nation towards another, further weakened the possibility of so-called Christendom showing a united front against the invading non-Christian and anti-Christian forces. England was isolated and at enmity with Spain (a part of the House of Habsburg: see maps alongside). France was surrounded by, and therefore at enmity with, the House of Habsburg, for the Habsburgs were then ruling in Spain, Naples, Netherlands, and parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Resistance to the Turkish invaders was increasingly a local affair, rather than a whole European concern. During the five-decade reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Empire grew to its fullest glory, encompassing the Caucuses, the Balkans, Anatolia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Suleiman had conquered Aden, Algiers, Baghdad, the Island of Rhodes, as well as the whole of South-Eastern Europe. His war galleys terrorized not only the Mediterranean Sea, but the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf as well. His one defeat was at the gates of Vienna in 1529. Vienna was the next stepping-stone on land, while the Mediterranean islands of Cyprus, Crete, Malta and Sicily being the targets to ensure total supremacy of the Mediterranean Sea and thus giving access to conquering all the Mediterranean lands surrounding it. |

THE TURKISH SIEGE OF MALTA AND CYPRUS TRIGGERS A MORE SERIOUS REACTION FROM EUROPE

1. THE BLOODY BUT SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE OF MALTA

1. THE BLOODY BUT SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE OF MALTA

2. THE BLOODY AND UNSUCCESSFUL DEFENSE OF CYPRUS

|

The Ottoman Attack on Cyprus Begins

The Ottoman Emperor, Selim II, invaded Cyprus. He was a drunkard and Cyprus was the source of his favorite vintage. Half the population were Greek Orthodox serfs laboring under the exacting rule of their Venetian Catholic masters, and they offered little resistance. The Venetian senate was half-hearted about fighting for the island. They had trade agreements with the Ottoman Empire and did not want to risk their economy and financial well-being over the loss of part of their territory. Upon receiving word of the invasion, senate members voted by the very small margin of 220 to 199 to defend it. As a ruler, Philip was harsh, saturnine, and austere. He embodied a scrupulousness that went beyond a personal failing to become a public vice, where there was no room for charity and far too much room for plottings and calculations, which, though they always had the protection of the Faith as their goal, were too admixed with lesser, baser metals than the gold of the monstrance.

Philip's knights had ranged into the New World and were carving out a vast empire, its extent virtually beyond imagining, whence came gold and other treasures. That, Philip knew, was the future. But to his immediate north was the menace. Europe Divided Philip was no friend of the Mohammedan, and the Muslims remained a persistent threat to Spain's possession of Naples and Sicily. Spanish vessels clashed throughout the Mediterranean with Barbary corsairs. At that very moment, Spanish infantry were suppressing the Morisco revolt of apparently unconverted Moors. But Philip trusted that Spain was well equipped to defeat the Muslims. That was old hat. But Protestantism was something relatively new. It was treason and heresy. And, though Philip would not have been so eloquent, it was worse: The North is full of tangled things and texts and aching eyes, And dead is all the innocence of anger and surprise, And Christian killeth Christian in a narrow dusty room, And Christian dreadeth Christ that hath a newer face of doom, And Christian hateth Mary that God kissed in Galilee . . . . Where the Austrian Habsburgs hoped against hope for conciliation with their own violent, Teutonic Protestants, Philip II trusted to his renowned Spanish infantry. They had the answer that Protestantism deserved. |

The Turks rolled through Cyprus, and after a forty-six day siege, the capital city of Nicosia fell on September 9, 1570. The 500 Venetians in the garrison surrendered on terms, but once the city gates were opened, the Turks rushed in and slaughtered them. Then they set on the civilian population, massacring twenty thousand people, "some in such bizarre ways that those merely put to the sword were lucky." Every house was plundered. To protect their daughters from rape, mothers stabbed them and then themselves, or threw themselves from the rooftops. Still, two thousand of the prettier boys and girls were gathered and shipped off as sexual prey and prostitution in the slave markets in Constantinople.

Who Will Come to the Rescue?

The Habsburg Empire was Europe's bulwark against Islamic jihad, but its timbers were being eaten away by the Protestants who diverted Catholic armies and even cheered on the Muslims, whom they saw as fellow enemies of the pope in Rome. In 1568, the emperor Maximilian, of the Austrian half of the Habsburg Empire, had agreed to a peace treaty with the Turk; and the Danube was reasonably, temporarily, quiet. In Spain, the other great pillar of the Habsburg Empire was Philip II. And for him, things were not quiet at all. We think of Philip II as dark and brooding, and so he was -- to the degree that it is surprising to remember that he was blue-eyed and fair-haired. But the lasting image, especially to those of English (even Catholic English) blood, is Chesterton's sketch; as King Philip is in his "closet with the Fleece about his neck": The walls are hung with velvet that is black and soft as sin, And little dwarfs creep out of it and little dwarfs creep in . . . . And his face is as a fungus of a leprous white and grey Like plants in the high houses that are shuttered from the day . . . . |

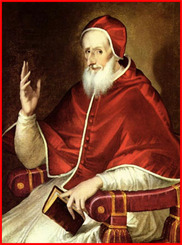

WHO WILL COME TO THE FIGHT? IS IT A KING? IS IT A PRINCE? NO... IT'S THE POPE!

Pope Saint Pius V (17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born

Antonio Ghislieri, a first name that he kept until 1518, when on entering the

monastery he took the name Michele (Michael), was Pope from 8 January 1566 to

his death in 1572, almost 7 months after the victory at Lepanto. He was a truly

pious Pius—disgusted with the worldliness and sinfulness of the clergy of his

age, he was a true reformer of his time. He is chiefly remembered for his role

in calling together the Council of Trent, which was the springboard for the

Catholic Counter-Reformation; he promulgated the rite of what is now known as

the “Tridentine Mass”; he reformed the Breviary; he declared St. Thomas Aquinas

a Doctor of the Church and promoted his writings; and did much to enhance the

sacred music of the Church.

Tough Cookie Pope While still a priest, he was prior of more than one Dominican priory during a time of great moral laxity; yet he insisted on discipline, and, in accordance with his own wishes, was appointed inquisitor (a member of the Inquisition) at Como. As his reformist zeal provoked resentment among the lax, he was forced to return to Rome in 1550. Pope Paul IV (1555–59), who, as Cardinal Carafa, had shown him special favor, conferred upon him the bishopric of Sutri and Nepi, and made him a cardinal, as well as later making him head of the Inquisition. Under Pope Pius IV (1559–65) he became bishop of Mondovi in Piedmont. While still a cardinal, Pius V gained a reputation for putting orthodoxy of Faith before personalities, prosecuting eight French bishops for heresy. He also stood firm against nepotism in the Church (favoritism granted to relatives), rebuking his predecessor Pope Pius IV to his face, when he wanted to make a 13-year old member of his family a cardinal, and when he wanted to subsidize a nephew from the papal treasury. This opposition to Pope Pius IV led to his dismissal from the palace and the end of his authority as inquisitor. Before Michele Ghislieri (the future Pius V) could return to his episcopate, Pope Pius IV died. On 8 January 1566, Ghislieri was elected to the papal throne as Pope Pius V. He was crowned ten days later, on his 62nd birthday. He was to reign only just over 6 years as Pope, but would achieve mighty deeds in that short time. Church Discipline Aware of the necessity of restoring discipline and morality at Rome to ensure success without, he at once proceeded to reduce the cost of the papal court after the manner of the Dominican Order to which he belonged, compel residence among the clergy, regulate inns, expel prostitutes, and assert the importance of adherence to the ceremonial in general and the liturgy of the Mass in particular. In his wider policy, which was characterized throughout by an effective stringency; the maintenance and increase of the efficacy of the Inquisition; and making sure that the enforcement of the canons and decrees of the Council of Trent had precedence over other considerations. Unifies the Liturgy Accordingly, in order to implement a decision of that council, he standardized the Holy Mass by promulgating the 1570 edition of the Roman Missal. Many abuses and personal deviations had entered the liturgy. Pius V made this Missal mandatory throughout the Latin rite of the Catholic Church, except where a Mass liturgy dating from before 1370 AD was in use. This form of the Mass remained essentially unchanged for 400 years until Pope Paul VI's revision of the Roman Missal in 1969–70, after which it has become widely known as the Tridentine Mass. The term "Tridentine" is derived from the Latin word Tridentinus, which means "related to the city of Tridentum (modern-day Trent, Italy)". It was in response to a decision of the Council of Trent that Pope Pius V promulgated the 1570 Roman Missal, making it mandatory throughout the Western Church, excepting those regions and religious orders whose existing missals dated from before 1370. |

Promotes Thomism

Pius V, who had declared Thomas Aquinas the fifth Latin Doctor of the Church in 1567, commissioned the first edition of Aquinas' opera Omnia (entire works). This work was produced in 1570. The works of St. Thomas Aquinas were given an authority just below that of Holy Scripture at the Council of Trent. St. Thomas’ thought was the guiding light of the Council. Battles the Protestant French Huguenots Pope Pius V recognized the danger of the attacks on papal supremacy in the Catholic Church at that time, and desired to limit their advancement. In France, where his influence was stronger, he took several measures to oppose the Protestant Huguenots. He ordered the dismissal of Cardinal Odet de Coligny and seven bishops, nullified the royal edict that tolerated the services of the Reformers, introduced the Roman catechism, restored papal discipline, and strenuously opposed all Catholic compromise with the Huguenot (Protestant) nobility. Excommunicates Elizabeth I of England In affairs of the state, Pius V excommunicated Elizabeth I of England for schism and the persecution of English Catholics during her reign. He also arranged the formation of the Holy League, an alliance of Catholic states. Although outnumbered, the Holy League famously defeated the Ottoman Empire, which had threatened to overrun Europe, at the Battle of Lepanto. Pius V attributed the victory to the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary and instituted the feast of Our Lady of Victory. In the list of more important bulls he issued, the famous bull "In Coena Domini" (1568) takes a leading place; but amongst others throwing light on Pope Pius V's character and policy there may be mentioned ► his prohibition of quaestuary (February 1567 and January 1570); ► the condemnation of Michael Baius, the heretical Professor of Leuven, Belgium (1567); ► the reform of the breviary (July 1568); the denunciation of homosexual behaviour by the clergy (August 1568); ► the banishment of the Jews from the ecclesiastical dominions, except Rome and Ancona (1569); ► the injunction of the use of the reformed Missal (July 1570); ► the confirmation of the privileges of the Society of Crusaders for the protection of the Inquisition (October 1570); ► the suppression of the Fratres Humiliati for vice and corruption (February 1571); ► the approbation of the new office of the Blessed Virgin (March 1571); ► the enforcement of the daily recitation of the Canonical Hours, that is to say, the Breviary (September 1571); ► and the obtaining of assistance against the Turks by offers of plenary indulgence (full pardon of temporal punishment due to sin) for all who would enroll for battle against the Turks (March 1572). Excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I of England His response to the Queen, Elizabeth I of England, audaciously assuming governance of the Church of England, included the Pope’s support of the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots, and her supporters in their attempts to take over England "ex turpissima muliebris libidinis servitute" “[from the sordid libidinous slavery to women]”. A brief English Catholic uprising, the Rising of the North, had just failed. Pius V then issued a bull, Regnans in Excelsis, dated April 27th, 1570, that declared Elizabeth I a heretic and released her subjects from their allegiance to her. In response, Elizabeth, who had thus far tolerated Catholic worship in private, now actively started persecuting Catholics for treason against the Crown. |

THE POPE TRIES TO FORM A 'HOLY LEAGUE" OUT OF AN UNHOLY EUROPE

|

The Holy League

Pope St. Pius V, in the last year of his papacy in 1571, tried to rally the nations of Europe to join in a Holy League. This Christian Coalition—the Holy League—was initially promoted by Pope Pius V to rescue the Venetian colony of Famagusta, on the island of Cyprus, which was being besieged by the Turks in early 1571, subsequent to the fall of Nicosia and other Venetian possessions in Cyprus in the course of 1570. However, its purpose would go beyond merely helping those on Cyprus, but its goal would be to stop, break and push back the Muslim Ottoman Turk invaders and their control of the eastern Mediterranean Sea, who threatened the entire continent of Europe if they could secure the invasion of the chief and strategically placed islands of the Mediterranean Sea. The pope had no sympathy for Protestants either, but for him, as for previous popes, Islam remained the real threat. The pope felt he had many urgent tasks to attend to, but the vital one was confronting the Islamic challenge. The War of Cyprus became the focus of Spain’s attention after Pope Pius V sent an envoy to urge Philip to join with him and Venice in a Holy League against the Turks. Philip agreed and negotiations opened in Rome. Among Philip's terms was the appointment of Don John as commander-in-chief of the Holy League armada. While he agreed that Cyprus should be relieved, he was also concerned to recover control of Tunis, where Turks had overthrown the regime of Philip's client Muslim ruler. Tunis posed an immediate threat to Sicily, one of Philip's kingdoms. Philip also had in mind the eventual conquest of Algiers, in North Africa, whose corsairs (pirate ships) posed a constant nuisance to Spain. Charles V had tried, and failed, to take it in the course of the Algiers expedition (1541). No Party-Pope, But 'Party-Pooper' Pope St. Pius V, like Philip, was no example of fat, jovial, easy-going, worldly Christianity such as the Italians preferred at that time. He thought the Church had seen too much of that, with the accompanying slackness (or even corruption) in Renaissance morals and an excessive generosity being shown by too many Catholics to Protestant error. He had never known the ‘high life’ or the ‘good life’. He was not ‘one of the crowd’. He was a former shepherd, an ascetic, a Dominican, and an inquisitor. Though agreeing on many things with Philip, he had a finer balanced spiritual core that kept him from Philip's failings. As a pope, he was a reformer, and brought a monastic purity to the organization and administration of the Church, to a review of the religious orders, to educating the faithful, to evangelizing, and to caring for the poor (which he did personally). As the spring of 1571 approached, almost five years of pleading on the part of Pius V, for Europe to unite in opposition to the threat of the Turkish fleet, seemed to have been without any effect; King Philip of Spain had pledged only a few ships to the Pope’s cause (because it seems he was saving them and building up his fleet for the future grand Spanish Armada of 130 ships and 26,000 soldiers and sailors, that was to sail to conquer England in 1588), and the Republic of Venice (then Italy’s primary naval power) was stalling. Pope Pius V understood the tremendous importance of resisting the aggressive expansion of the Turks better than any of his contemporaries appear to have. He understood that the real battle being fought was spiritual; a clash of creeds was at hand, and the stakes were the very existence of the Christian West. |

After Years of Pleading...

In a papacy of great achievements, the greatest came on March 7th, 1571, on the feast of his fellow Dominican, St. Thomas Aquinas. At the Dominican Church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome, after five years of pleading, and over a dozen unsuccessful attempts to form a Christian alliance against the Turks, as he begged the nations for help, Pope Pius V finally managed to form the Holy League. Genoa, the Papal States, and the Kingdom of Spain put aside their jealousies and pledged to assemble a fleet capable of confronting the sultan’s war galleys before the east coast of Italy became the next front in the war between the Christianity and Islam. Venice A Menace The day was not a total triumph, though. Venice refused to join. Though at war with the Turks over Cyprus, the Venetians never failed to consider their economy and financial well-being! They might well lose Cyprus, but a fast peace afterward would lead to the resumption of normal trade relations with the Turks. Moreover, the loss of the Venetian fleet in an all-out battle with the sultan’s galleys would be a disaster for a state so dependent on seaborne commerce. Walking back across the Tiber, the old monk wept for the future of Christendom. He knew that without the galleys of Venice, there was no hope of a fleet strong enough to face the Turks. Compromising Catholics The rest of Europe ignored Pius’s call for a new crusade. In fact, the Queen of England, Elizabeth I, through her spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, actively enlisted the aid of the Turks in her wars against Spain. France had openly traded with the Turks for years and as recently as 1569 had drawn up an extensive commercial treaty with them. For years the French had allowed Turkish ships to harbor in Toulon, France, and the oars that rowed Turkish galleys came from Marseilles. The cannons that brought down the walls of Szigetvar were of French design. With Venice at war with Constantinople, markets once filled by Venetian goods were open to France. Redeeming France from utter disgrace were the Knights of Saint John of Malta, who sent their galleys to join the Holy League, eager to do battle with Islam. Answer to Prayer As the Pope prayed for Venice to answer a higher call, a new breed of fiery priests led by stirring preachers like St. Francisco Borgia, superior general of the Jesuits, inflamed the hearts of Christian Europeans throughout the Mediterranean with their sermons against Islam. Enough Venetians must have been listening, because on May 25th, Venice at last joined the Holy League. By fits and starts, with hesitation and quarreling on the part of a few of the principal players, the fleet of the Holy League was forming. The Holy League was then formally concluded on May 25th, 1571. Its members now were the Papal States, the Habsburg states of Spain, Naples and Sicily, the Republic of Venice, the Republic of Genoa, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchies of Savoy, Parma and Urbino and the Knights of Malta. |

DON JUAN OF AUSTRIA IS THE SURPRISE CHOICE TO LEAD THE FLEET

|

The man chosen by Pius V to serve as Captain General of the Holy League did not falter: Don John of Austria, the illegitimate son of the late Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, and half-brother of Philip II, King of Spain. Before he died, the Emperor Charles, on several occasions, saw his son, now a youth of eleven. Yet John did not know that Charles was his father. In his will, Charles had made provision for John, and expressed hope that he would enter the clergy and pursue an ecclesiastical career.

Charles' other son and heir to the throne, Philip II of Spain, returned from Brussels in Belgium in 1559, aware of his father's will. Philip had John brought to him for a hunting expedition. When Philip appeared, John was told to dismount and make proper reverence to his king. When John did so, Philip asked him if he knew the identity of his father. When the boy did not know, Philip embraced him and explained that they had the same father and thus were brothers. Philip, however, was strict regarding protocol: John was not to be addressed as "highness", the form reserved for royals and sovereign princes. In formal style he was "your excellency", the address used for a Spanish grandee, and known as Don Juan de Austria. Don John did not live in a royal palace, but maintained a separate household. Philip allowed Don John the incomes allocated to him by Charles so that he might maintain the status proper to the son of an emperor and brother of a king. In public ceremonies, Don John stood, walked or rode behind the royal family, but ahead of the grandees. Though his father, Emperor Charles V, had wanted John to enter the clergy, this did not attract John. He had his sights set on a military career. He was a great horseman, a great swordsman, and a great dancer. With charm, wit, and good looks in abundance, he was popular among the ladies of court. Since childhood he had cultivated a deep devotion to the Blessed Virgin. He spoke Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish, and kept a pet marmoset and a lion cub that slept at the foot of his bed. He was twenty-four years old. However, it seems his reputation was slightly tarnished by the fact that he was apparently a womanizer and had allegedly fathered two illegitimate children. Don John, therefore, never did fulfill his father's and brother's hopes of joining the clergy as a military career proved more to his liking. In 1565, the 18-year-old left for Barcelona to join the armada for the relief of Malta which was being besieged by the Ottoman Turks. In 1566, he was dubbed the 245th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. In 1568, when Don John turned 21, Philip appointed him Captain General of the Sea and commander of Spain’s Mediterranean galley fleet. Don John embarked with the fleet that spring, under the guidance of Philip's confidant, Don Luis de Requeséns, Grand Commander of Castile, and assisted by veterans such as Don Álvaro de Bazán, 1st Marquis of Santa Cruz. He patrolled Spain's coast and chased Barbary corsairs, his first foray into combat. The young commander had distinguished himself in combat against Barbary corsairs (pirates) and in the Morisco rebellion in Spain, a campaign in which he demonstrated his capacity for swift violence, when the threat called for it, and restraint when charity demanded it. The example of Galera and Don John's determined advance intimidated other Morisco villages, which soon began to surrender to Don John's forces. Through 1570 the revolt gradually sputtered out as its leaders quarreled, sought individual advantage, and murdered each other, while the Turks and their Barbary allies turned to the invasion of the Venetian colony of Cyprus. To eliminate the possibility of further revolts in Granada, Philip dispersed its Moorish (Morisco) population in small groups among the Old Christian towns and villages of the Castilian hinterland, reportedly hoping they would assimilate. Eventually, Philip III would order the expulsion of all Moriscos from Spain in 1609. While Don John finished the pacification of Granada, negotiations dragged on in Rome. In the summer of 1570 Philip sailed for Cyprus under the pope's admiral Marcantonio Colonna. In charge of Philip's contingent was the Genoese Gian Andrea Doria, a great-nephew of the renowned Andrea Doria. On reaching the Turkish coast in September, Colonna and the Venetians wished to press on to Cyprus while Doria argued that the season had grown too late. Then news arrived that Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, had fallen, and only the port of Famagusta held out. Sickness hit the Venetian fleet and a consensus grew that it was best to return to port. The weather turned ugly and while Doria reached port in good order, the Venetians were storm-battered. Among the Christian allies, animosities became open while the Turks tightened their siege of Famagusta. The Venetians repaired their galley fleet and readied six heavily armed galleasses. The Pope hired twelve galleys from the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The dukes of Savoy and Parma also provided galleys, and Alexander Farnese sailed in one. When the League was formally signed in May, Don John was designated commander-in-chief and given his many instructions by Philip. With the instructions came a warning not to involve himself with women, which, among other instructions, were ignored by Don John. It was late July before he sailed with the Spanish squadron from Barcelona, and mid-September before the entire Holy League armada got underway from Messina. Don John was determined to fight, rallying allies and quelling their mutual suspicions. The banner for the fleet, blessed by the pope, reached the Kingdom of Naples (then ruled by the King of Spain) on August 14th, 1571. There, in the Basilica of Santa Chiara, it was solemnly consigned to John of Austria, who had been named leader of the coalition after long discussions between the allies. The fleet moved to Sicily and leaving Messina reached (after several stops) the port of Viscardo in Cephalonia, where news arrived of the fall of Famagusta and of the torture inflicted by the Turks on the Venetian commander of the fortress, Marco Antonio Bragadin. Taking the young warrior by the shoulders, Pope St. Pius V looked Don John of Austria in the eye and declared, "The Turks, swollen by their victories, will wish to take on our fleet, and God—I have the pious presentiment—will give us victory. Charles V gave you life. I will give you honor and greatness. Go and seek them out!" |

MEANWHILE .... BACK ON POOR BESIEGED CYPRUS ...

|

Fighting to the End

In late summer of 1571, as Don John was making his way to the harbor at Messina, to take command of his fleet, the situation on Cyprus was growing more desperate. The Venetian colonists had claimed the lives of some 50,000 Turks with their intrepid defense of Famagusta, on Cyprus, but when their gunpowder and supplies were exhausted, when they had eaten their last horse, their shrewd governor, Marcantonio Bragadino, sent a message to the Turkish commander, Lala Mustafa, asking for terms. The Turks agreed to give the remaining Venetian soldiers passage to Crete on fourteen Turkish galleys in exchange for the surrender of the city. The Greek Cypriots would be allowed to retain their property and their religion. The Price of Saying "No!" On August 4, 1571, Bragadino, with a small entourage including several young pages, met with Mustafa and his advisors in the Turkish general’s tent. Mustafa lecherously demanded Bragadino’s page for sexual sport, Antonio Quirini, as a hostage for the fourteen galleys. When Bragadino calmly refused, he and his men were pushed out of the tent by Mustafa’s guards. The governor, Bragadino, was bound and forced to watch as his attendants were hacked to pieces. The pages were led off in chains. The Turks thrice thrust the Venetian governor’s neck on the executioner's block and thrice lifted it off. Instead of his head, they cut off his nose and ears. To prevent his bleeding to death, they cauterized the wounds with hot irons. Double-Crossing Turks

The Venetian soldiers of the garrison, unaware that Mustafa had broken the terms of the surrender, began their march down to the galleys, expecting passage to Crete. Once aboard, the Venetians were set upon by Turkish soldiers, who stripped them of their clothes and chained them to the oars. From their benches they witnessed some of the horrifying ordeal to which the Turks now subjected Bragadino. |

Human or Animal Behavior?

First the Turks fitted the governor with a harness and bridle and led him around the Turkish camp on his hands and knees. Ass panniers filled with dung were slung across his back. Each time he passed Lala Mustafa’s tent he was forced to kiss the ground. Then he was strung up in chains, hoisted over a galley spar, and left to hang for a time. Finally, the courageous governor was dragged into the city square and lashed to the pillory, where the Turks flayed him alive. Witnesses said they heard him whispering a Latin prayer. He died "when the executioners knife reached the height of his navel." The diabolical orgy did not end there. Mustafa had the governor’s skin stuffed, hoisted it up the mast of his galley, and joined the Ottoman fleet headed west. Don John Takes Command As Bragadino was losing his life to the Turkish monsters, Don John was inspecting his ships. Of the 206 galleys and 76 smaller boats that constituted the Holy League fleet, more than half came from Venice. The next largest contingent came from Spain, and included galleys from Sicily, Naples, Portugal, and Genoa, the latter owned by the Genovese condottiere admiral, Gianandrea Doria. Not only was Doria renting his services and the use of his ships to Philip at costs thirty percent higher than Philip paid to run his own galleys, he was lending the money to the Spanish king at fourteen percent! The balance of the galleys came from the Holy See. Tough Rules Don John took charge of his fleet and promptly forbade women from coming aboard the galleys. He declared that blasphemy among the crews would be punishable by death. The whole fleet followed his example and made a three-day fast. Not Just Physical Battle, but Spiritual too! By September 28, the Holy League had made its way across the Adriatic Sea and was anchored between the west coast of Greece and the Island of Corfu. By this time, news of the death of Bragadino had reached the Holy League, and the Venetians were determined to settle the score. Don John reminded his fleet that the battle they would soon engage in was as much spiritual as physical. Using the Spiritual Weapons Pius V had granted a plenary indulgence to the soldiers and crews of the Holy League. Priests of the great orders, Franciscans, Capuchins, Dominicans, Theatines, and Jesuits, were stationed on the decks of the Holy League’s galleys, offering Mass and hearing confessions. Many of the men who rowed the Christian galleys were criminals. Don John ordered them all unchained, and he issued them each a weapon, promising them their freedom if they fought bravely. He then gave every man in his fleet a weapon more powerful than anything the Turks could muster: a Rosary. And then there was ... the Rosary! On the eve of battle, the men of the Holy League prepared their souls by falling to their knees on the decks of their galleys and praying the Rosary for hours on end. Back in Rome, and up and down the Italian Peninsula, at the behest of Pius V, the churches were filled with the faithful telling their beads. In Heaven, the Blessed Mother, her Immaculate Heart aflame, was listening. |

Web Hosting by Just Host