| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

ST. JOHN MARIE BAPTISTE VIANNEY

Feast: August 8th

Feast: August 8th

|

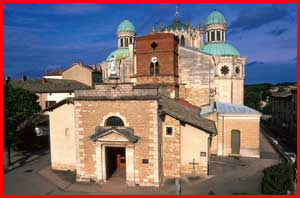

On February 9th, 1818, a young priest anxiously walked along a narrow road that led to the village of Ars in Southern France. Ars was to be his parish and he to be the Curé. As he was arriving he knelt down to pray, and while doing so, a strange idea prompted him to say: “This parish will not be able to contain the number of those who shall journey here.”

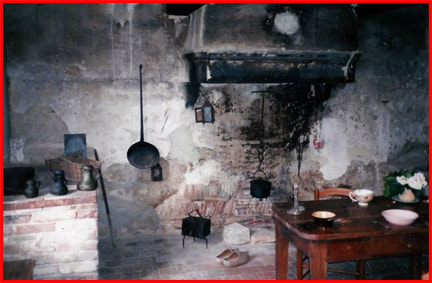

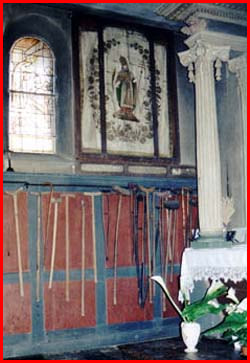

This indeed was a strange prophecy. Why should anyone want to come to Ars? It was at that time in a squalid state: 40 clay houses scattered in a valley through which a small stream slowly flowed. The church was in poor repair with an unkempt cemetery behind it. The inhabitants were ordinary farmers and indifferent as far as the Catholic Faith was concerned, spending their leisure drinking and gossiping. Yet, despite itself, Ars soon became famous, for God had sent a blessing by sending this new Curé. The priest took the challenge that lay before him. The French revolution had left its diabolical marks of freethinking and indifference, but he would soon shake the people out of their lethargy by preaching the uncompromising truths of salvation. The life of the Curé d’Ars, as described by one who witnessed and shared his labors, is in itself a more signal glory of the miraculous, than any of those by which it was glorified: John Baptiste Marie Vianney was born at Dardilly, a village near Lyons, in a simple farmhouse situated among beautiful vineyards. The house of the Vianneys had been known for generations upon generations as the home of the poor, the well-known resort of all wandering beggars. In the year 1770, St. Joseph Labre was one of these mendicants. The parents of John Vianney, Matthieu and Marie, in a high degree the traditional virtues of their people. Matthieu was pious and thoroughly honest in a century of corruption in France, and his wife added the virtues of sweetness and tenderness, which sprang from a deeply interior nature, fitting for the mother of a Saint. Before the birth of St. John-Marie, the oldest of six children, she often offered him to God and the Blessed Virgin, making a secret vow to consecrate him to the altar. The woman who attended his mother at the birth proclaimed: “Either this child will be a great Saint or a great villain!” At eighteen months old he had already learned to join his hands in prayer and to lisp the names of Jesus and Mary. Marie Vianney would awaken her children daily, that she might see them offer their hearts to God. The virtues of his mother passed into his heart: St. Vianney credits, after God, his mother, with his singular graces, which he would need in plenitude. The Saint had trouble going through the seminary and lived in an age of anti-religious rebellion, when Satan appeared triumphant in French culture. The appeal at the time was to “liberty, equality, and fraternity.” Their clamor had always been vicious in nature, obliterating the rights of God, rendering man “sovereign,” but now it had actually worsened. But Saints do not surrender to dissolute social pathology. Vianney’s age of reason was the archetypal assertion that sanctity was not a historical phenomenon, and Vianney was to prove it wrong. Vianney did things thought to be impossible and he did them with an innocent blatancy. In the next 41 years this priest would convert 80,000 or more hardened sinners of every sort. Later, pilgrims from all over, as many as 120,000 annually, came to see him, hear him preach and tell him their sins, and he would heal their souls and sometimes even their bodies. A vocation is a precious and mysterious thing. St. Alphonsus Liguori estimated that one out of three receives a vocation. St. John Bosco was of the opinion that one out of four receives a vocation. If today we experience a lack of vocations, we must not blame God, but ourselves. In order for grace to be effective and fruitful it must fall on fertile ground, otherwise the seed will be choked out by worldly pleasures. At the time of Vianney’s youth, because of the anti-clerical, anti-ecclesiastical French Revolution that broke out in 1789, priests who did not sign an oath to the state were sent into exile or forced into hiding. If caught these priests went to the guillotine. Soon the doors of the church at Dardilly were closed and the practice of the Catholic Faith forbidden. But in nearby Lyons there were still 30 priests loyal to Rome who continued to administer the Sacraments, in secrecy, and at the risk of their lives. The Vianneys not only managed to keep their Faith during this period of persecution, but in fact, grew stronger because of it, as God so often brings good out of evil. The courageous family would have nothing to do with priests who took the oath of allegiance to the French constitution, which was anti-Church, known as juror priests, nor would they permit their children to attend the public schools, even though a heavy fine was imposed on those who kept their children away. Instead, they continued to say their daily prayers and provide catechetical instruction in the home. Occasionally a refractory or loyal-to-Rome priest would come to offer Mass in secret. The evils of the French Revolution, which caused to the defection of so many priests, gave John Vianney a great horror of sin and at great zeal for devotion and piety. He would say: “Oh, if I were a priest, I should want to win ever so many souls for God!” In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power, becoming absolute monarch. Whatever his failures and misdeeds and sins, Bonaparte liberated the Church, opening the church doors so that Mass could once more be publicly celebrated and Our Lord Eucharistically enthroned on the altar. John-Marie was quick to make visits to the Blessed Sacrament. While he had advance spiritually during the persecution, his formal education had suffered, as he knew only how to read and write, but nothing else. Now that Vianney could openly pursue his vocation, another trial awaited because Matthieu would not give his consent for his son to go to the seminary. The elder Vianney was growing old and he needed the work of Vianney on the farm. In vain did Marie plead with her husband. The whole time, St. John bore all in silence, submissive to God’s holy will. Meanwhile, the Fr. Balley, one of the two priests who most influenced Vianney, had opened a small school in the rectory at Écully, to prepare boys for the priesthood. Matthieu conceded and permitted John to study there. Fr. Balley was reluctant at first because John-Marie was so poorly educated and was already nineteen, but changed his mind when he learned how much Vianney knew of the Saints. John Marie enthusiastically tackled his textbooks, but Latin was stumbling block for him. In desperation he made a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. John Regis, asking for enough success to become a priest. His prayers were answered later, although he never mastered Latin. In 1807 he was confirmed, adding Baptiste to his name. The following year a third obstacle presented itself. Bonaparte had grown desperate for more soldiers, so, although he was supposedly free of the draft, he along with the other seminarians, was summoned to the ranks of the Grand Army. He obeyed. After two illnesses he was ordered to a regiment on the Spanish lines. As went along on the road he said his Rosary. Toward late afternoon, exhausted, he stopped to rest, wondering where he would find shelter in the winter weather. Suddenly a man appeared, telling Vianney that his name was Guy. Guy picked up the Saint’s pack and led him up a mountainous path to a hut. The next morning Vianney thought that Guy was a deserter and feared his company as he would be considered one, too. To avoid being caught, he went higher in the mountains, staying with a kind widow; in gratitude he taught her children. Fortunately, in 1810, Bonaparte granted a general amnesty and John-Marie was free to return home. The people in the mountain hamlet of Les Robins made a cassock for him because they loved him so much. That February, in bliss to have her beloved son return, Marie Vianney died. After that, St. John-Marie had no longer any worldly attachment. By now he was 24. When he returned to the seminary he made a consecration to Mary, placing his complete trust in her, committing all his good works, past, present, and future to her motherly protection, in the manner recommended by St. Louis de Montfort, the great saint of the French Vendee region, and who was so instrumentally in preserving the Faith in that part of France during the persecution. De Montfort had left a legacy so strong the Revolution could not destroy it. Vianney studied in the major seminary at Lyons, and was by then known as the Abbè Vianney because he had received the tonsure the previous year. Among the 250 seminarians, he was known for his asceticism, penance, modesty, and recollection. Despite all this, six months later the authorities felt compelled to dismiss him, who is now the Patron Saint of Parish Priests, because of poor academics. Almost in despair, he heard a voice instructing him to not fret as he would one day be a priest. The Fr. Balley would not give up either, and soon sent John back for an examination for the minor orders and the diaconate. This time he was examined in French and he passed, in fact it was recorded that he “gave very good, satisfactory answers.” Meanwhile, all the Archbishop was concerned about was piety. When told that Vianney was a model of piety, the Bishop summoned him for ordination, saying that the “grace of God will do the rest.” On July 2nd, the Feast of the Visitation, he was made a subdeacon. On August 12th, 1815, he was ordained a priest forever. At first, the faculties were withheld from him for Confession, but God has a sense of humor, for soon Vianney would be hearing Confessions up to 18 hours a day. His work as parish priest for Ars was difficult―it took him a few years to close down the taverns, and eight years to stop the Sunday buying and selling, and a whole twenty-five years to get the people to dress modestly and cease dancing so impiously. He prayed constantly for sinners but he endured much suffering from them, calumnies, incessant diabolical disturbance, exhaustion, constant fevers. He said: “To suffer lovingly, is to suffer no longer.” His diet was a self-inflicted penance: boiled potatoes, usually days old, never more than two in a day. If someone gave him a loaf of bread, he would exchange it for a crust from a beggar. To his penitents, on the other hand, he gave easy penances, saying: “I give them a light penance and perform the rest myself.” At first, out of routine the villagers would come to Sunday Mass at that was all. Even the slightest excuse would suffice with which to absent themselves. It was only on Sundays, that Vianney was able to correct them in general. During the week he would visit the farms and cottages when everyone was eating the noon meal. He would stand, leaning in the doorway talking with them about farming. But before he had left he had managed to turn the subject to Heaven. Later in the day he was seen walking through the fields saying the Rosary. He was such an eloquent speaker that many priests and bishops came to hear him preach; so clearly did he teach the truths of the Faith, that his listeners were startled to remark on their sublime simplicity. The Saint did not consider his village converted until all 200 villagers were observing the Ten Commandments, the Six Precepts of the Church and the fulfillment of daily duties. He preached about modesty in dress, for he knew that modesty is the outward appearance of purity, and he demanded modesty at all times, not just in church. But the sin that caused him to weep most was the sin of blasphemy, the profanation of God’s Holy Name. He used to say that it was a miracle that blasphemers were not struck dead on the spot. He warned the villagers that “if the sin of blasphemy is prevalent in your home, it―the home―will perish.” From this it would seem that St. Vianney was intolerant and uncompromising when it came to sin, and indeed, he was, like his Patron Saint, St. John the Baptist. And just as he lay axe to the root, he also built up, explaining the Mysteries of the Faith, such as the Incarnation and spotless Virginity of Mary with such unction that people would shed tears. His delight was to teach children the catechism, which he did every day. After a while, the adults came, too. Those who had grown up during the French Revolution were in complete ignorance of their Faith; he taught them the Rosary and loved to tell them about the Saints. The Curé d’Ars repeatedly stressed the importance of the Blessed Sacrament and established a Eucharistic Guild. With time the church was never empty, because someone was always there before the Blessed Sacrament. The sanctuary had been refurbished with graceful statues and pictures, because Vianney believed that the mere sight of a holy image could convert a soul. [Catholic Tradition concurs, of course.] By 1827, peace pervaded Ars―because everyone living there was living in conformity to God’s Divine Plan. All of France had heard of Ars and many came seeking the peace there and found it in the confessional of the saintly priest. With unparalleled discernment he would discover the source of any problem and unhesitatingly insist on its being treated or cut away. Then he would prescribe the means for staying in the state of grace, and how to reject occasions of sin. The time spent in the confessional for each penitent was short―for the confession lines were very long and time was precious; sometimes he heard as many as 400 confessions within a single day. One day, upon leaving the confessional, to say Mass, he passed by a lady who was ready to leave in despair of ever getting to see him. He pleasantly told her: ”You are not very patient, my child! You have been here only three days and you want to go home? You must remain fifteen days and pray to Saint Philomena to tell you what is your vocation and after that, come and see me!” She did so and later became a nun. At another time he came out of the confessional and bade a woman out of turn to come in, somehow knowing that she could wait no longer. He was the mother of 16 children. These stories relate the wonderful compassion of the Saint. In truth, he was the living testimony to the Mercy of God. And he would sometimes weep for the penitent, whom he considered as not weeping enough. Space here does not permit more such accounts, but we must tell you about his love for Saint Philomena. St. John Marie Vianney was renowned for miracles. A simple prayer, a word, or a touch of his hand was all that was needed to perform miraculous cures, but to him it was the curing of the soul that was of importance. And he did not like any attention he received or praise. Thus, he made an agreement with St. Philomena, his favorite saint, that he would send all those that were deserving of cures to her; he would sing her praises and she do the work. Until that time, Philomena was little-known. Her relics had only recently been found in the catacombs. In fact, he is credited with the promotion of devotion to her for there were those who did not believe about St. Philomena. Vianney testified that she and Our Lady appeared to him on occasions when he needed some Heavenly assistance. And always he would say, when asked how he kept up his arduous schedule: “With Our Lady and Saint Philomena we get on well together.” Before we close with our little exposition, we must provide a brief explanation of his harassment by the devil. Satan prefers to be forgotten so that he can do his work all the more proficiently. If this tactic does not work, he has recourse to all sorts of manifestations to unsettle a soul. With St. John Vianney none of his tactics were successful. Thus, the devil assumed a bodily form to terrify the priest, which he managed to do for a time. Imagine yourself being dragged out of bed by the ankles, as he was, on many occasions, or hearing hideous screams, or Satan himself singing in the night. This is what happened to the Curé d’Ars from 1824-1858, hundreds of times a year. After a while he stopped being terrified―all that Satan could bring about was a loss of sleep, which was at most only 2 to 3 hours anyway. One night the bed was set aflame, still to no avail. The devil was heard to say: “If there were three such priests as you in France, my kingdom in France would be ruined!” The Saint spent long years in heroic suffering and towards the end of his life he had the joy of seeing his Heavenly Mother and Queen honored by Pope Pius IX when he declared the Blessed Virgin Mary to “be preserved from all stain of sin, from the first moment of her conception” on December 8th, 1854. This the saint had always held to be true, but now it was official. At the beginning as his vocation as a confessor, one of his jealous confrères warned him in a letter that a priest who knew as little theology as he, should not dare to enter the confessional. Vianney liked letters like that actually. But the people knew, and long before his death he was revered as a saint, but the Curé of Ars did not enjoy that. The only attention worthy of having was his before the Blessed Sacrament, which he had done all his life. At age 73, still keeping the same routine, he was ready for eternal rest. On July 29th, 1859, he collapsed for the last time saying: “I can do more! Sinners will kill the sinner!” After receiving the Last Sacraments and Holy Viaticum, on August 4th, the soul of John-Marie Baptiste Vianney went to Heaven. His body remains at Ars today, incorrupt. |

Web Hosting by Just Host