| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Holy Ghost

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE NAME OF THE SAINT YOU WISH TO VIEW

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

THE SEVEN HOLY SLEEPERS

commemorated on July 27th

commemorated on July 27th

Who doesn't like talking about sleep? There's only one thing better than talking about sleep—and that is actually SLEEPING! What a dream-like existence! But who were these “Seven Holy Sleepers”? Sounds like a tempting vocation, doesn’t it? “O Lord, help me be a Holy Sleeper!” Maybe we could recruit Saints Peter, James and John of Gethsemane fame, to be our patron saints! Well, let us put such silly thoughts to bed and wake up to the life and predicament of the Holy Sleepers that could soon be coming our way too!

|

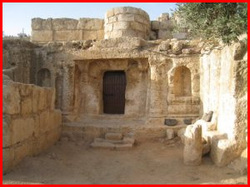

The Seven Holy Sleepers of Ephesus is a story of a group of youths, who hid inside a cave outside the city of Ephesus around 250 AD, to escape a persecution. The persecuting Roman Emperor Decius ordered them imprisoned in a sealed cave, so that they would die there as punishment for being Christians. Having fallen asleep inside the cave, they purportedly awoke approximately 180 years later during the reign of Theodosius II, following which they were reportedly seen by the people of the now-Christian city before dying.

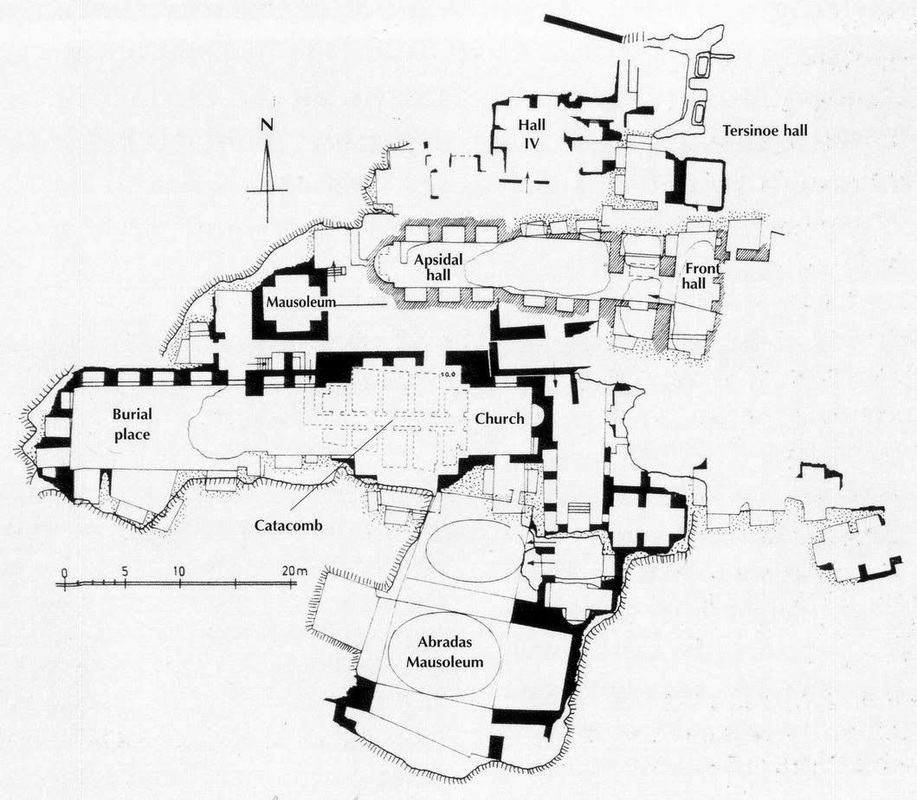

The earliest version of this story comes from the Syrian bishop Jacob of Sarug (c. 450–521), which is itself derived from an earlier Greek source, now lost. An outline of this story appears in Gregory of Tours (b. 538, d. 594), and in Paul the Deacon's (b. 720, d. 799) History of the Lombards. The best-known Western version of the story appears in Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend. In the Liturgy of the Church, the Roman Martyrology mentions the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, under the date of July 27th, as follows: "Commemoration of the seven Holy Sleepers of Ephesus, who, it is recounted, after undergoing martyrdom, rest in peace, awaiting the day of resurrection." The Byzantine Calendar commemorates them with feasts on August 4th and October 22nd. Around 250 AD, the Roman Emperor Decius, who had decreed the persecution of Christians, came to Ephesus and gave orders that temples be built in the center of the city, so that all the people might join him in worshiping false gods. He further ordered that all Christians were to be rounded up and put in chains, either to sacrifice to the gods or to die; and the Christians in Ephesus were so afraid of the threatened punishments that friends betrayed friends, fathers their sons, and sons their fathers. Seven young Christian men named Maximianus, Malchus, Marcianus, Dionysius, Johannes, Serapion, and Constantinus —held high rank in the palace—Maximianus was the son of the Ephesus city administrator, and the other six youths were sons of illustrious citizens of Ephesus. The youths were friends from childhood, and all were in military service together. These seven refused to sacrifice to the idols. Instead they hid in their houses and devoted themselves to fasting and prayer. For this they were denounced by informants and brought before Decius to reply to the charges. Appearing before the emperor, the young men confessed their faith in Christ. Their military belts and insignia were quickly taken from them. Decius permitted them to go free, however, hoping that they would change their minds while he was off on a military campaign. Thus the emperor gave them some time to come to their senses, before he returned to the city. These young men had to act fast. They gave their all their wealth and property to the poor, took only a few coins with them and went to take refuge on Mount Celion (Anchilos) where they agreed to live a holy life like hermits, and to pray and prepare for their eventual death. From their group of seven, Malchus was chosen to dress as a beggar and go into town each week for supplies and food. Meanwhile Decius returned to Ephesus and inquired after these seven men. They were betrayed and denounced for having given away their wealth to the poor and by deserting the city. Decius then commanded that the seven be brought before his presence and forced to sacrifice. The seven men hiding in the mountain cave, heard of his return and then, after saying their last prayer, ate their last meal in fear and trembling. Then with souls filled by grace and stomachs filled with food, by the will of God, they all fell asleep. The emperor told his soldiers to find them, and when found asleep in the cave, Decius ordered the cave entrance to be blocked and sealed with huge stones, so that they would die of hunger; thus they were buried alive. Two fellow Christian men, Theodorus and Rufinus, wrote an left an inscription with the names of the martyrs and an account of their martyrdom, leaving it concealed among the stones that sealed the cave. Years passed, the empire became Christian, and the emperor Theodosius (a Christian) was reigning—either Theodosius the Great (379-395) or Theodosius the Younger (408-450). Almost two hundred years later in the thirtieth year of the reign of the Christian emperor Theodosius, there was an outbreak of heresy and a widespread denial of the resurrection of the dead. While this controversy went on, a good citizen of Ephesus, a rich landowner, named Adolios, was seeking to build a cattle-stall on Mount Celion, for use by his shepherds and sheep. He hired stone masons and they found a good collection of very fine stones stacked very deliberately in a pile outside of a cave—which, little did they know, was the cave in which the seven young martyrs had been sealed by Decius. Once the stones—that blocked the cave—were removed, the seven young men awoke to the light of day—thinking they have slept only one night. The seven companions were seriously worried about the actions being taken by the Emperor Decius. Not being sure of the outcome of all this, Malchus was sent into town as usual to buy extra food for their sustenance, in case they might be forced, by circumstances, to stop making these weekly trips for food into the city. But the city which Malchus entered was visibly changed. It was the same city, but he was confused. There were notable changes, such as huge crosses on all the imperial property, and he kept hearing people talking and using the name Christ. He went to a bread baker to buy bread, but when he offered his coins, the sellers, surprised, told each other that this youth had found some ancient treasure. Seeing them talking about him, Malchus thought they were getting ready to turn him over to the emperor. He became afraid and told them to keep the bread and the money—but they thought he was suspicious and caught hold of him. Word of this reached St. Martin, the bishop, and he ordered the citizens to bring this youth and the money to him. The bishop looked at the coins. The inscription on the coins was hundreds of years old. The bishop and his proconsul questioned him and found that Malchus was extremely confused. They too were confused. The youth told the bishop that he and his friends were hiding from the Emperor Decius, and he would take the bishop and show him the cave. The bishop thought this over, then told the proconsul that God was trying to make them see something through this youth. So they set out with him and a great crowd followed them. Malchus went ahead to alert his friends, and the bishop came after him and found among the stones the letter sealed with two silver seals. He called the people together and read the letter to them. They marveled at what they heard, and, seeing the seven saints of God, their faces like roses in bloom, sitting in the cave, all fell to their knees and gave glory to God. The emperor Theodosius was summoned. When he arrived, their faces shone like the sun, and the saints told him their story. Every one rejoices at this proof of the resurrection of the body. The emperor prostrated himself before them and gave praise to God, then rose and embraced each one and wept over them, saying: “Seeing you thus, it is as if I saw the Lord raising Lazarus from the dead!” St. Maximianus (one of the Seven Sleepers) proclaimed that God must have done this, “so that you may believe without the shadow of a doubt in the resurrection of the dead.” The sleepers, then having improvised the occasion by a long discourse, bowed their heads to the ground, praising God, and then back into their asleep—this time permanently—yielding up their spirits as God willed that they should do, while all looked on in amazement. The emperor wanted to build golden tombs for them, but they appeared to him in a dream and asked to be buried in the earth inside their cave. The cave was adorned with precious gilded stones, a great church was built over it, and every year the feast of the Seven Sleepers is kept. A brick church was built above the seven original tombs, with mosaic floors and marble revetments by Emperor Theodosius. A large, domed mausoleum was added to the cave in the 6th century. Frescoes on the walls and vaults are mainly vegetal decorations. As we might expect, pilgrimages to the site of the cave were extremely popular through the end of the fifteenth century, as is evidenced from the graffiti on the walls in both Latin and Greek. It also became a favored spot of burial in Late Antiquity. Theodosius on his pilgrimage in the sixth century saw the tombs of the Seven Sleepers, and according to a ninth century writer, visitors to the cave were shown seven incorrupt bodies. The 12th century Russian pilgrim Daniel saw the same. Daniel also says that many were buried there. Although pilgrimages can be shown throughout the medieval centuries, the most famous was probably one sponsored by the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, Edward the Confessor, in response to a vision. The story of this particular pilgrimage to Ephesus was to be forever immortalized in a stone frieze in the chapel dedicated to Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey. Below is plan of layout of the shrine to the Seven Holy Sleepers before it was destroyed and fell into disrepair. |

Web Hosting by Just Host