| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

RELATED LINKS

| Novena to Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal | The Facts and Story of the Miraculous Medal |

| Enrollment in the Miraculous Medal | The Life of St. Catherine Laboure | The Miracles of the Miraculous Medal |

| Novena to Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal | The Facts and Story of the Miraculous Medal |

| Enrollment in the Miraculous Medal | The Life of St. Catherine Laboure | The Miracles of the Miraculous Medal |

CLICK ON THE NAME OF THE SAINT YOU WISH TO VIEW

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

ST. CATHERINE LABOURÉ

THE SAINT OF THE MIRACULOUS MEDAL

Part One

WHERE ON EARTH WAS ST. CATHERINE LABOURÉ BORN?

|

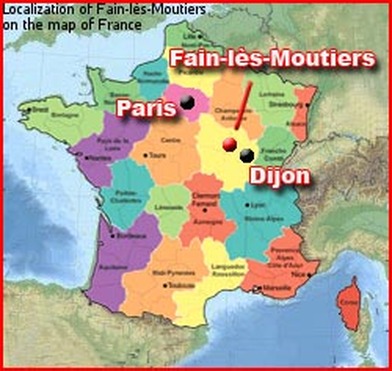

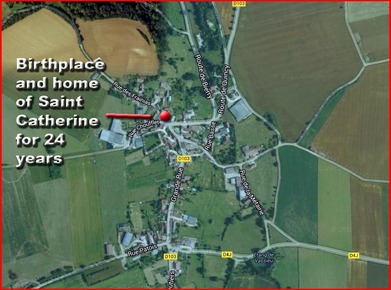

Catherine Labouré was born in a very small village called Fain-lès-Moutiers, which is located a little east of central France. Fain-lès-Moutiers is within the department of Côte-d'Or

of the French region of Bourgogne (Burgundy). The village of Fain-lès-Moutiers comes under the administration of the township of Montbard, which in turn is a part of the district of Montbard.

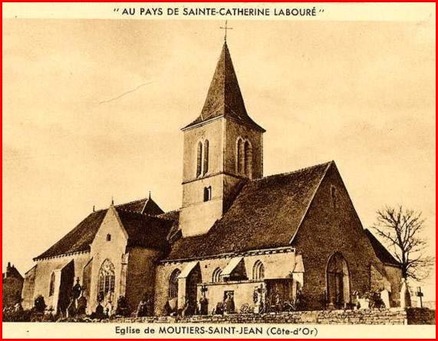

The nearest church to Fain-lès-Moutiers was in Moutiers-Saint-Jean. The population of Fain-lès-Moutiers was 147 in 1999, 204 in 2006 and 208 in 2007, with a current population density of 35 inhabitants per square mile. The number of houses in Fain-lès-Moutiers was 99 in 2007. These consisted of 80 main residences, 12 second or occasional homes and 7 vacant homes. So it still is what it was in Catherine's time, a tiny little village. |

When the Virgin Mary and Her Blessed Son were born into the world, the world had almost no knowledge of their coming, nor of the new covenant between God and man that they heralded. It was much the same in 1806 when Catherine Labouré, the visionary of the Miraculous Medal, was born. She was a country farm girl, hidden in a pocket of the Burgundian hills in France. Certainly the brilliant skeptical world of Voltaire and the proud world of Napoleon Bonaparte would have snubbed her. Yet, Heaven did not snub her, but chose her to herald a new Marian era that began, what many call, the Age of Mary.

Fain-lès-Moutiers, a small agricultural plain nestled among trees, which in 1830 also numbered around two hundred inhabitants. The village of Fain was dependent on the district abbey, therefore, the old word "Moutiers" [derived from the Latin monasterium] was added to its name. Fain-lès-Moutiers is of the region of Burgundy, an area highly celebrated for spiritual riches, where God has seemed to have dowered men very plentifully with his best gifts: e.g., remarkable intellects or holiness, creative genius in the arts. Dijon, so very near to Fain, is the birthplace of some renowned Catholics: St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Doctor of the Church and founder of the monastery at Clairvaux; St. Jeanne de Chantal, the foundress of the Visitation Nuns; and Bossuet, the famous French bishop and theologian, renowned for his sermons.

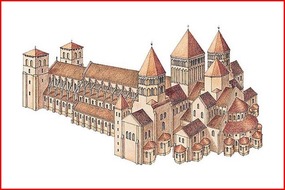

Burgundy abounds with great works of art: Romanesque style and Gothic style churches, along with paintings, sculptures, monuments and art objects of every kind. From a religious standpoint, Burgundy triggers the name of Cluny, the abbey that was the nursery of popes, of which, during the Middle Ages, there were more than two thousand abbeys among its dependencies of which at Citeaux, the cradle of Cistercians and of Trappists, and at Paray-le-Monial, where we receive the great devotion to the Sacred Heart. Catherine Labouré, therefore, was born in a place whereon the Spirit of God had been pleased to breathe.

Fain-lès-Moutiers, a small agricultural plain nestled among trees, which in 1830 also numbered around two hundred inhabitants. The village of Fain was dependent on the district abbey, therefore, the old word "Moutiers" [derived from the Latin monasterium] was added to its name. Fain-lès-Moutiers is of the region of Burgundy, an area highly celebrated for spiritual riches, where God has seemed to have dowered men very plentifully with his best gifts: e.g., remarkable intellects or holiness, creative genius in the arts. Dijon, so very near to Fain, is the birthplace of some renowned Catholics: St. Bernard of Clairvaux, Doctor of the Church and founder of the monastery at Clairvaux; St. Jeanne de Chantal, the foundress of the Visitation Nuns; and Bossuet, the famous French bishop and theologian, renowned for his sermons.

Burgundy abounds with great works of art: Romanesque style and Gothic style churches, along with paintings, sculptures, monuments and art objects of every kind. From a religious standpoint, Burgundy triggers the name of Cluny, the abbey that was the nursery of popes, of which, during the Middle Ages, there were more than two thousand abbeys among its dependencies of which at Citeaux, the cradle of Cistercians and of Trappists, and at Paray-le-Monial, where we receive the great devotion to the Sacred Heart. Catherine Labouré, therefore, was born in a place whereon the Spirit of God had been pleased to breathe.

It was about 6:00 p.m., the time when the evening Angelus is traditionally prayed, on May 2nd [the feast day of St. Zoé],1806, when Catherine Labouré was born to Pierre Labouré, Catherine’s father, and her mother, Madeleine Gontard. Her parents chose Catherine as her baptismal name and entered the name, Catherine, on the civil register of births as well. This is significant to the fact as long as she remained in the world, Catherine was known as Zoé, and not until she began her religious life did she resume her baptismal name.

|

Her father, Pierre Labouré, owned the largest farm in the village and was an educated man, having studied for the priesthood in his youth. Her mother, Madeleine Louise Gontard, was a former school mistress, whose family was well respected.

Catherine was the ninth of eleven children and during her adolescence her younger sister Marie Antoinette, or “Tonine”, was her close companion. While Tonine was the friend and confidante of her childhood and adolescence, Catherine's mother was the source of her sanctity and spitual devotion, for Madame Labouré took pains to instill in her a special love of God and to lead her in the ways of holiness. |

Sadly her beloved mother died when Catherine was only nine years old. In the midst of her terrible grief at her mother's passing, Catherine turned to Our Lady. Climbing up on a chair, she reached for a statue of the Blessed Virgin that stood high on a shelf in her mother's bedroom, clasped it to her breast, and said aloud: "Now, dear Blessed Mother, you will be my mother." The fact that Catherine meant what she said, is very evident from the deepening of her spiritual life and ever increasing devotion to Jesus and the Blessed Virgin Mary.

PART TWO

LIFE AFTER DEATH

LIFE AFTER DEATH

Life after the death of his wife and Catherine's mother, was not easy. Pierre Labouré was disconsolate, feeling indeed beside himself at the death of his beloved wife and perfect companion. Already autocratic and a little harsh in his manner. he seems to have become more difficult. This would explain why of all his sons Auguste alone--and he was in poor health--remained at home with him. The others had all taken themselves to Paris.

|

Pierre entrusted the household to Marie-Louise, then aged twenty, and sent Catherine and Tonine to be cared for by his sister at Saint-Rémy. She was married to a vinegar merchant called Jeanrot, and was herself the mother of four little girls. In this small village, nine miles from Fain, where the château of St. Bernard's uncles still stands, the two orphan girls spent the years 1816 and 1817 and were educated with their cousins in a religious atmosphere. Sixty-five years later, one of them was to testify at the ecclesiastical inquiry into Catherine's holiness that at that early date she was already exemplary in her behavior.

During the next two years, she and Tonine lived with thei kindly aunt, Marguerite Jeanror, in the nearby village of Saint-Remy. Catherine was pleased to discover that Saint-Remy had a resident priest, which is something that her hometown did not have, and, for the first time in her life, Catherine was given an organized course of instruction in Catholic doctrine and guidance in cultivating the spiritual virtues. It was the only formal education she was ever to receive, a strange and mysterious thing, for she came of educated parents and her brothers and sisters all had more advanced schooling in varying degrees. And so it is hard not to see here design of heaven to keep Catherine ignorant, so that the divine origin of her visions might be the more apparent. At Saint-Remy, Catherine began to prepare for her first Communion and to withdraw more and more from the playful life of childhood into a solemnity beyond her years. "She had no interest in games," was the way Tonine put it. At the beginning of 1818 Pierre Labouré came for his two children and brought them home with him. Very soon after, the time had come for the elder to make her first Communion, and she did this in the church of Moutiers-Saint-Jean on January 25. 1818. Tonine says of Catherine: "My sister impressed everyone with her fervor. And later she told me that on that day she had made up her mind that, like Marie-Louise, our big sister, she too would consecrate herself to God." Tonine added: "From the time of her first Communion, she became entirely mystic." As a matter of fact. Marie-Louise entered the Convent of the Daughters of Charity two months later. Catherine rejoiced in her sister's happiness, and wishing her to have no regrets about leaving home assured her that she was well able to take her place in directing the household. Pointing to Tonine, Catherine said to her father: "We two are quite well able to keep house." She was only twelve years old, and Tonine scarcely ten, yet events showed that she had not been presumptuous, for during the following ten years she indeed kept the house going well. All the evidence produced at the inquiries preceding her beatification proves this. One witness declared: "From the day after her first Communion, she gave herself up entirely to work, she accustomed herself to fatigue, she established herself in habits of orderliness and initiative. She was only fourteen when the single household servant that the Labourés had, decided to leave her place in order to get married. It was Catherine who insisted that no one else be hired, and the two sisters added the servant's duties to their own." |

Together they kept house, cooked the meals, did the washing and mending, took care of the poultry bins, the stables and the garden. "In summertime, Catherine carried her father’s lunch to him wherever he might be working in the fields in the company of a dozen hired hands."

It was a tremendous task because in addition to her father, there were three brothers and a sister still at home for Catherine to care for, and one of these, the youngest, was an invalid, who required constant nursing. Also, there were fourteen hired men, whose dinner must be carried to them in the fields. And in addition to the cooking and cleaning there was the laundry and sewing. All of this meant for very long days, going late to bed and early to rise for little Catherine, who was at this time only a young teenager.

In the yard of the farmhouse the large dovecote with its great tower sheltered between seven and eight hundred pigeons. "My sister it was who usually took care of feeding these birds," said Tonine. "They would fly to her, circling about her head, getting caught in her hair and sitting on her shoulders. She would pause happily in the midst of them, and it made a charming picture to see her there." Her brothers recalled that "she did all things well and quickly," and that it was "but rarely that our father, despite his natural severity, had even a slight reproach for her."

Catherine's life was a life of work from her twelfth to her twenty-second year.

It was a tremendous task because in addition to her father, there were three brothers and a sister still at home for Catherine to care for, and one of these, the youngest, was an invalid, who required constant nursing. Also, there were fourteen hired men, whose dinner must be carried to them in the fields. And in addition to the cooking and cleaning there was the laundry and sewing. All of this meant for very long days, going late to bed and early to rise for little Catherine, who was at this time only a young teenager.

In the yard of the farmhouse the large dovecote with its great tower sheltered between seven and eight hundred pigeons. "My sister it was who usually took care of feeding these birds," said Tonine. "They would fly to her, circling about her head, getting caught in her hair and sitting on her shoulders. She would pause happily in the midst of them, and it made a charming picture to see her there." Her brothers recalled that "she did all things well and quickly," and that it was "but rarely that our father, despite his natural severity, had even a slight reproach for her."

Catherine's life was a life of work from her twelfth to her twenty-second year.

Her Spiritual Life and Hard Work Protects Her During Adolescence

Catherine passed through the period of adolescence without being troubled or upset. Tonine tells us that "in all things where evil was concerned she was quite direct and innocent." Her imagination and her thoughts were never occupied with fleshly desires, and she kept her childlike innocence of mind and body to the end of her life. Already, at this time, her true piety was remarked.

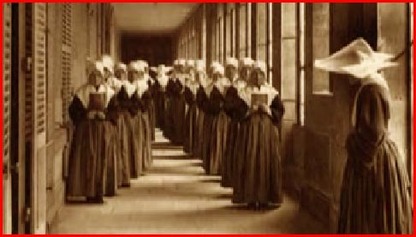

As there was no resident priest at Fain, it was the pastor of the parish of Moutiers-Saint-Jean who attended to the spiritual needs of the villagers, and who came on Sundays to say Mass for them. Other religious services were held at Moutiers-Saint-Jean, where, in addition to the parish church, there was a house of the Daughters of Charity to which a chapel was attached.

Catherine was not satisfied with going every afternoon to pray in her local church of Fain, where her family had their own private oratory in a recess to the left of the high altar. She would arise before dawn, almost each day of the week, so that she might walk some six miles in the predawn darkness to the nearby village of Moutiers to hear Mass, sometimes in the parish church, at others in the Sisters’ chapel.

In addition to her daily Mass, throughout the day she managed to slip away to the village chapel across the lane from her home; there her favorite devotion was to kneel in prayer before a old painting of the Annunciation of the Archangel Gabriel to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

At the inquiry a woman of eighty who had known the sisters when she was a child declared: "What examples those girls were! They were admired as perfect housewives. They took no part in worldly amusements and only went out to help the villagers or to attend services in the church. I can see them now as on Sunday after Mass they would bid a pleasant good day to young girls of their own age as they left the church, and then would hasten homeward where their household duties awaited them."

It was her attitude while at prayer that most impressed those who saw her. She had no use for benches or cushions, and in winter as well as in summer knelt on the uncovered pavement. Here she remained immovable and as though transfixed, her eyes upon the tabernacle. "One would have taken her to be an angel," the witnesses at the inquiry afterward declared. It was at this time that she contracted the arthritis of the knees of which she was never cured.

We finally learn that from the age of fourteen she fasted in secret on Fridays and on Saturdays. When Tonine discovered this and threatened to tell their father, Catherine replied: "Very well go ahead.” Pierré Labouré pressed her to cease her fasting: finding her set upon continuing and yet not impaired in health, he gave up the attempt.

Deeply Spiritual

"She was already a mystic." says Tonine. The word is well chosen but it should be explained, for in it is found the key to our saint's life.

The mystic is one attuned to mystery. For such a one the invisible world is more present and real than the outer world that surrounds us. In this inner region the mystic seems to move sure-footedly, while others find their way only by faith and at the cost of much effort, whereas certain others, such as the materialists, become wholly lost.

The soul of the mystic is attuned to God and to His saints, and it is with them that it holds converse. In this state it is indeed as an interchange that prayer is conceived of, so that what to many is a labored monologue becomes for the mystic a dialogue. So great is the soul's absorption in prayer that the mystic seems to be rapt out of himself when prays; it appears as if he were hearing what he had listened for, as if he were seeing what he had sought.

This wondrous gift is far from being of the same nature, as are the gifts of the speculative intellect, nor is it to be measured by them. It might better be compared to the artistic gifts of privileged genius, for example to the faculty of a musician who hears what he describes as harmony from heaven, music to which he alone is perceptive and which he alone can note down and develop.

Catherine was not at all gifted in the field of the speculative intellect, she was even less endowed in respect to imagination, originality of mind, literary or artistic sensitivity. She was, however, withdrawn and thoughtful; she possessed judgment and good sense; and above all, she was the recipient of special insights which came to her as a result of prayer.

There is no doubt that the chief of the graces given to her was this aptitude, this capacity, to feel and to savor the realities of the supernatural world. Yet another grace must, be taken into account. for without it the first might have been less advantageous to her: this second grace was that she was born at Fain-les-Moutiers and that she passed her childhood there.

Just as is true of God's other gifts, it is true of the mystical capacity that it can grow or decrease or even disappear entirely. Greed, impurity.ambition, absorption in unworthy pleasure may account for its loss, while its lasting growth can be ascribed to renunciation, humility, recollection and faithfulness in prayer.

What might have become of Catherine had she been placed in surroundings dominated by the search for mere pleasure and the love of money? What if she had spent her days, from morning until evening, in a factory or in an office? What if her leisure had been divided between hurrying hither, thither and yon and the reading of silly trash, or between day-dreaming by the fireside and plunging, into chattering and ceaseless exercise of the voice? Would not her soul have succumbed to such influences? Would it not have fallen into the poor, ordinary pattern, its own characteristics being stamped out and annihilated?

Fain-les-Moutiers, nestling among its trees, moved according to the rhythm of Nature, not to that of the machine. There time was taken for eating, for sleeping, for talking, or for being silent. There was a time for thought and for listening, time to tend the garden, to play with the pigeons, to see the sun set, and to pray to God. There was not much bad example to be seen: evil hid itself and was called by its right name. 'Money did not usurp the place of God, and spiritual values were accorded the first place. which the Gospel says they should have. It was not felt at Fain-les-Moutiers that individuality should be suppressed; there was freedom for each to follow his bent. A soul permeated by a sense of the inner life could find opportunity for reflection; no one was required to submerge his true nature in a banal conformity. In a word, at Fain-les-Moutiers, a mystic such as Catherine found opportunity to hasten to the confrontation with God to which He was pleased to lead her.

She Preferred Jesus instead of Marriage

Her chestnut hair, her lovely eyes and her noble face, as well as the fact that she was known to be a virtuous and healthy girl, attracted suitors who wished to marry her. When her father first spoke to her of such an offer, she told him what Tonine had known for a long while, "that she was betrothed to Jesus alone, and that He alone would be her spouse."

At least twice her father returned to the charge, but met with no greater success, despite the fact that the offers which were made had come from men who were worthy and honorable. It seems that Pierre Labouré did not really resent her refusals. Tonine would soon be twenty years old and might marry young; he was himself about sixty, and he may have cherished the notion that Catherine, by remaining a spinster, would be someone on whom he might lean in his old age.

However, when she told him, on attaining her majority, of her intention to enter the religious life, he became annoyed. He had his own notions about the rights of God and the duties of children. He thought that since he had three daughters it was all very -well that one had dedicated herself to God, but he felt that the others should seek their happiness in the world.

Catherine passed through the period of adolescence without being troubled or upset. Tonine tells us that "in all things where evil was concerned she was quite direct and innocent." Her imagination and her thoughts were never occupied with fleshly desires, and she kept her childlike innocence of mind and body to the end of her life. Already, at this time, her true piety was remarked.

As there was no resident priest at Fain, it was the pastor of the parish of Moutiers-Saint-Jean who attended to the spiritual needs of the villagers, and who came on Sundays to say Mass for them. Other religious services were held at Moutiers-Saint-Jean, where, in addition to the parish church, there was a house of the Daughters of Charity to which a chapel was attached.

Catherine was not satisfied with going every afternoon to pray in her local church of Fain, where her family had their own private oratory in a recess to the left of the high altar. She would arise before dawn, almost each day of the week, so that she might walk some six miles in the predawn darkness to the nearby village of Moutiers to hear Mass, sometimes in the parish church, at others in the Sisters’ chapel.

In addition to her daily Mass, throughout the day she managed to slip away to the village chapel across the lane from her home; there her favorite devotion was to kneel in prayer before a old painting of the Annunciation of the Archangel Gabriel to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

At the inquiry a woman of eighty who had known the sisters when she was a child declared: "What examples those girls were! They were admired as perfect housewives. They took no part in worldly amusements and only went out to help the villagers or to attend services in the church. I can see them now as on Sunday after Mass they would bid a pleasant good day to young girls of their own age as they left the church, and then would hasten homeward where their household duties awaited them."

It was her attitude while at prayer that most impressed those who saw her. She had no use for benches or cushions, and in winter as well as in summer knelt on the uncovered pavement. Here she remained immovable and as though transfixed, her eyes upon the tabernacle. "One would have taken her to be an angel," the witnesses at the inquiry afterward declared. It was at this time that she contracted the arthritis of the knees of which she was never cured.

We finally learn that from the age of fourteen she fasted in secret on Fridays and on Saturdays. When Tonine discovered this and threatened to tell their father, Catherine replied: "Very well go ahead.” Pierré Labouré pressed her to cease her fasting: finding her set upon continuing and yet not impaired in health, he gave up the attempt.

Deeply Spiritual

"She was already a mystic." says Tonine. The word is well chosen but it should be explained, for in it is found the key to our saint's life.

The mystic is one attuned to mystery. For such a one the invisible world is more present and real than the outer world that surrounds us. In this inner region the mystic seems to move sure-footedly, while others find their way only by faith and at the cost of much effort, whereas certain others, such as the materialists, become wholly lost.

The soul of the mystic is attuned to God and to His saints, and it is with them that it holds converse. In this state it is indeed as an interchange that prayer is conceived of, so that what to many is a labored monologue becomes for the mystic a dialogue. So great is the soul's absorption in prayer that the mystic seems to be rapt out of himself when prays; it appears as if he were hearing what he had listened for, as if he were seeing what he had sought.

This wondrous gift is far from being of the same nature, as are the gifts of the speculative intellect, nor is it to be measured by them. It might better be compared to the artistic gifts of privileged genius, for example to the faculty of a musician who hears what he describes as harmony from heaven, music to which he alone is perceptive and which he alone can note down and develop.

Catherine was not at all gifted in the field of the speculative intellect, she was even less endowed in respect to imagination, originality of mind, literary or artistic sensitivity. She was, however, withdrawn and thoughtful; she possessed judgment and good sense; and above all, she was the recipient of special insights which came to her as a result of prayer.

There is no doubt that the chief of the graces given to her was this aptitude, this capacity, to feel and to savor the realities of the supernatural world. Yet another grace must, be taken into account. for without it the first might have been less advantageous to her: this second grace was that she was born at Fain-les-Moutiers and that she passed her childhood there.

Just as is true of God's other gifts, it is true of the mystical capacity that it can grow or decrease or even disappear entirely. Greed, impurity.ambition, absorption in unworthy pleasure may account for its loss, while its lasting growth can be ascribed to renunciation, humility, recollection and faithfulness in prayer.

What might have become of Catherine had she been placed in surroundings dominated by the search for mere pleasure and the love of money? What if she had spent her days, from morning until evening, in a factory or in an office? What if her leisure had been divided between hurrying hither, thither and yon and the reading of silly trash, or between day-dreaming by the fireside and plunging, into chattering and ceaseless exercise of the voice? Would not her soul have succumbed to such influences? Would it not have fallen into the poor, ordinary pattern, its own characteristics being stamped out and annihilated?

Fain-les-Moutiers, nestling among its trees, moved according to the rhythm of Nature, not to that of the machine. There time was taken for eating, for sleeping, for talking, or for being silent. There was a time for thought and for listening, time to tend the garden, to play with the pigeons, to see the sun set, and to pray to God. There was not much bad example to be seen: evil hid itself and was called by its right name. 'Money did not usurp the place of God, and spiritual values were accorded the first place. which the Gospel says they should have. It was not felt at Fain-les-Moutiers that individuality should be suppressed; there was freedom for each to follow his bent. A soul permeated by a sense of the inner life could find opportunity for reflection; no one was required to submerge his true nature in a banal conformity. In a word, at Fain-les-Moutiers, a mystic such as Catherine found opportunity to hasten to the confrontation with God to which He was pleased to lead her.

She Preferred Jesus instead of Marriage

Her chestnut hair, her lovely eyes and her noble face, as well as the fact that she was known to be a virtuous and healthy girl, attracted suitors who wished to marry her. When her father first spoke to her of such an offer, she told him what Tonine had known for a long while, "that she was betrothed to Jesus alone, and that He alone would be her spouse."

At least twice her father returned to the charge, but met with no greater success, despite the fact that the offers which were made had come from men who were worthy and honorable. It seems that Pierre Labouré did not really resent her refusals. Tonine would soon be twenty years old and might marry young; he was himself about sixty, and he may have cherished the notion that Catherine, by remaining a spinster, would be someone on whom he might lean in his old age.

However, when she told him, on attaining her majority, of her intention to enter the religious life, he became annoyed. He had his own notions about the rights of God and the duties of children. He thought that since he had three daughters it was all very -well that one had dedicated herself to God, but he felt that the others should seek their happiness in the world.

|

Catherine is Sent to Paris

Conditions at home became so difficult and so strained that a change became imperative and Pierre Labouré hit upon the idea that Catherine should make a visit to Paris. He expected her to return fully cured of unreasonable notions. There were five of the sons of old Labouré at Paris: Jacques was a wine merchant, Joseph was in the business of glass bottles, Antoine was a pharmacist, Pierre was a clerk, Charles operated a restaurant. Charles had already lost his wife early, and it was to his house that Catherine went in the autumn of 1828. The restaurant in which she began to work was at No. 20, Rue de I'Echlquler, in the district of Notre Dame de la Bonne Nouvelle, where many building projects were under way at the time. The place was frequented by workmen; it was a sort of "bistro" as we would call it nowadays. Charles had worked out an agreement with one of the important construction firms, and lie supplied meals for the masons, carpenters, painters, pavers, and other workers employed by the firm. |

Catherine did her best to wait on all these in an atmosphere compounded of cheap wine, tobacco fumes, musty onion soup, vulgar talk and swearing. She remained here for some months in a state of great unhappiness, but even more resolute than ever in her determination to follow her vocation to the religious life.

At about this time, or a little earlier, she seems to have had a dream which was a source of much comfort to her in her troubles with her father. Toward the end of her life she spoke of it to her sister, Marie-Louise:

"I dreamed that I was at prayer in our own little oratory in the church at Fain. I was alone in the church. Suddenly there came forth from the sacristy a white-haired priest, vested for Mass and carrying his chalice. He walked solemnly toward the altar, but as he passed by me he turned his head and looked fixedly at me with eyes which, although full of goodness, gleamed like fire. This shook me to the depths of my being.

"Mass began. -Now. every time that he turned to say Dominus vobiscum, this old man looked at me so searchingly that I was unable to bear it. When he finished saying Mass he returned to the sacristy where he remained for a few remained to unvest. Then I saw him again at the door, and he beckoned to me to come forward. But I was so frightened that I fled at once.

“ However, I was by no means rid of him, for as I was returning home I stopped to visit one of our sick friends to hear how she was, and whom did I see behind me but the self-same old priest! He had followed me. And this time he spoke to me, saying, 'My child, it is all very well to visit the sick . . . but you are running, away from me. ... Nevertheless, the day will come when you will be with me, for God has plans for you. Do not forget this!'

"These words of the old priest marked the end of my dream."

Catherine herself was unable to write, and it was no doubt to Charles that she dictated the letters which now reached her sister-in-law, the wife of Hubert Labouré, and her own sister, Marie-Louise. who was at the time superior at the Daughters of Charity at Castelsarrasin (Tarn-et-Garonne) . Madame Hubert Labouré, who was originally Jeanne Gontard and a blood cousin of her husband, was the proprietress of a pensionnat or boarding school for young girls at Châtillon-sur-Seine (Cote-d'Or), about thirty miles front Fain-les-Moutiers.

At about this time, or a little earlier, she seems to have had a dream which was a source of much comfort to her in her troubles with her father. Toward the end of her life she spoke of it to her sister, Marie-Louise:

"I dreamed that I was at prayer in our own little oratory in the church at Fain. I was alone in the church. Suddenly there came forth from the sacristy a white-haired priest, vested for Mass and carrying his chalice. He walked solemnly toward the altar, but as he passed by me he turned his head and looked fixedly at me with eyes which, although full of goodness, gleamed like fire. This shook me to the depths of my being.

"Mass began. -Now. every time that he turned to say Dominus vobiscum, this old man looked at me so searchingly that I was unable to bear it. When he finished saying Mass he returned to the sacristy where he remained for a few remained to unvest. Then I saw him again at the door, and he beckoned to me to come forward. But I was so frightened that I fled at once.

“ However, I was by no means rid of him, for as I was returning home I stopped to visit one of our sick friends to hear how she was, and whom did I see behind me but the self-same old priest! He had followed me. And this time he spoke to me, saying, 'My child, it is all very well to visit the sick . . . but you are running, away from me. ... Nevertheless, the day will come when you will be with me, for God has plans for you. Do not forget this!'

"These words of the old priest marked the end of my dream."

Catherine herself was unable to write, and it was no doubt to Charles that she dictated the letters which now reached her sister-in-law, the wife of Hubert Labouré, and her own sister, Marie-Louise. who was at the time superior at the Daughters of Charity at Castelsarrasin (Tarn-et-Garonne) . Madame Hubert Labouré, who was originally Jeanne Gontard and a blood cousin of her husband, was the proprietress of a pensionnat or boarding school for young girls at Châtillon-sur-Seine (Cote-d'Or), about thirty miles front Fain-les-Moutiers.

|

In her reply to Catherine's letter, Marie-Louise congratulated her sister on her vocation and encouraged her to persevere: "You tell me that you wish you were already tasting the happiness of the religious life, but remember this: if God is calling you, there is no one who can stop you from responding to your vocation.”

She went on to advise Catherine very strongly to fix her choice on the congregation of the Daughters of Charity, and she closed her letter with these words: “I join with our dear sister-in-law in her suggestion that you visit her. Whatever maybe the final outcome, it is certainly needful that you improve your French, and that you learn how to write and how to figure." These lines indicate that it was Madame Hubert Labouré who had proposed the idea of receiving at her pensionnat the daughter who had been practically put out of her father’s house. This would enable her to escape from the unhappiness she felt in Paris. |

Was it perhaps that Madame Hubert Labouré was the niece of his dear departed wife, and that she recalled to him her beauty and her goodness, that the obstinate Pierre Labouré agreed to hear of the plan? As we shall see, he returned to the matter twice during the following months. To begin with, he agreed that Catherine leave Paris and establish herself at Châtillon-sur-Seine. She arrived there, as it appears, in time for the reopening of classes in September 1829.

PART THREE TO FOLLOW SOON

Web Hosting by Just Host