| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

| 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station | 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station |

| 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

| 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

The Greatest and Most Important Time in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS | LITANIES FOR PASSIONTIDE |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | The Last Days of Christ | Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

CLICK ON ANY LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS | LITANIES FOR PASSIONTIDE |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | The Last Days of Christ | Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

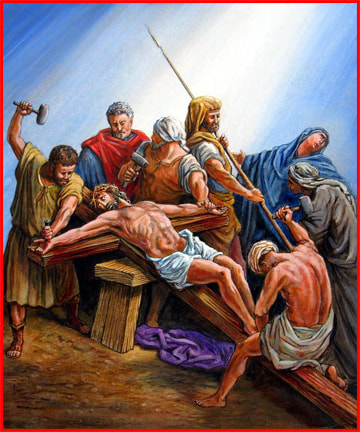

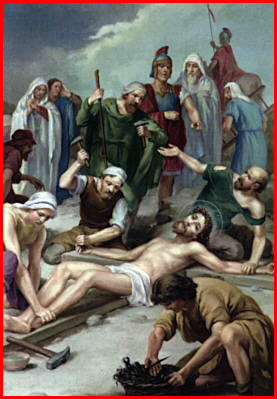

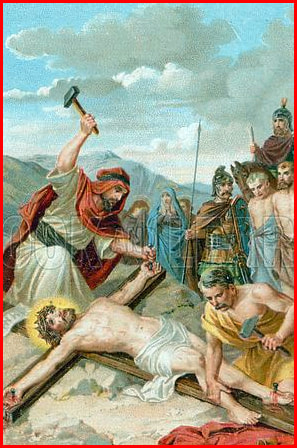

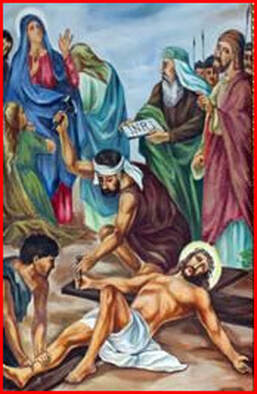

THE ELEVENTH STATION : JESUS IS NAILED TO THE CROSS

“St. Augustine assures us that there is no spiritual exercise more fruitful or more useful than the frequent reflection on the sufferings of Our Lord. St. Albert the Great, who had St. Thomas Aquinas as his student, learned in a revelation that by simply thinking of or meditating on the Passion of Jesus Christ, a Christian gains more merit than if he had fasted on bread and water every Friday for a year, or had beaten himself with the discipline once a week till blood flowed, or had recited the whole Book of Psalms every day” (The Secret of the Rosary, St. Louis Marie de Montfort, “Twenty-Eighth Rose”).

|

The following passage is taken from The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ by Blessed Anne Catherine Emmerich

Jesus was so weakened from suffering and loss of blood that He could not support Himself for more than a few moments; He was covered with open wounds, and His shoulders and back were torn to the bone by the dreadful scourging He had endured. He was about to fall when the executioners, fearing that He might die, and thus deprive them of the barbarous pleasure of crucifying Him, led Him to a large stone and placed Him roughly down upon it, but no sooner was He seated, than they aggravated His sufferings by putting the crown of thorns again upon His head. They then offered Him some vinegar and gall, from which, however, He turned away in silence. The executioners did not allow Him to rest long, but made Him rise and place Himself on the cross, so that they might nail Him to it. Then, seizing His right arm they dragged it to the hole prepared for the nail, and having tied it tightly down with a cord, one of them knelt upon His sacred chest, a second held His hand flat, and a third taking a long thick nail, pressed it on the open palm of that adorable hand, which had ever been open to bestow blessings and favors on the ungrateful Jews, and, with a great iron hammer, drove it through the flesh and far into the wood of the cross. Our Lord uttered one deep but suppressed groan, and His blood gushed forth and sprinkled the arms of the archers. I counted the blows of the hammer, but my extreme grief made me forget their number. The nails were very large, the heads about the size of a crown piece, and the thickness that of a man's thumb, while the points came through at the back of the cross. The Blessed Virgin stood motionless; from time to time you might distinguish her plaintive moans; she appeared as if almost fainting from grief, and Magdalen was quite beside herself. When the executioners had nailed the right hand of Our Lord, they perceived that His left hand did not reach the hole they had bored to receive the nail, therefore they tied ropes to His left arm, and, having steadied their feet against the cross, pulled the left hand violently, until it reached the place prepared for it. This dreadful process caused our Lord indescribable agony, His breast heaved, and legs were quite contracted. They again knelt upon Him, tied down His arms, and drove the second nail into His left hand; His blood flowed afresh, and His feeble groans were once more heard between the blows of the hammer, but nothing could move the hard-hearted executioners to the slightest pity. The arms of Jesus, thus unnaturally stretched out, no longer covered the arms of the cross, which were sloped; there was a wide space between them and His armpits. Each additional torture and insult, inflicted on Our Lord, caused a fresh pang in the heart of His Blessed Mother; she became white as a corpse, but as the Pharisees endeavored to increase her pain by insulting words and gestures, the disciples led her to a group of pious women who were standing a little farther off. The executioners had fastened a piece of wood at the lower part of the cross, under where the feet of Jesus would be nailed, that thus the weight of His body might not rest upon the wounds of His hands, as also to prevent the bones of His feet from being broken when nailed to the cross. A hole had been pierced in this wood to receive the nail when driven through His feet, and there was likewise a little hollow place for His heels. These precautions were taken lest His wounds should be torn open by the weight of His body, and death ensue before He had suffered all the tortures which they hoped to see Him endure. The whole body of our Lord had been dragged upward, and contracted by the violent manner with which the executioners had stretched out His arms, and His knees were bent up; they therefore flattened and tied them down tightly with cords; but soon perceiving that His feet did not reach the bit of wood, which was placed for them to rest upon, they became infuriated. Some of their number proposed making fresh holes for the nails which pierced his hands, as there would be considerable difficulty in removing the bit of wood, but the others would do nothing of the sort, and continued to vociferate: “He will not stretch Himself out, but we will help Him!” They accompanied these words with the most fearful oaths and imprecations, and having fastened a rope to His right leg, dragged it violently until it reached the wood, and then tied it down as tightly as possible. The agony which Jesus suffered from this violent tension was indescribable; the words, “My God! My God!” escaped his lips, and the executioners increased His pain by tying His chest and arms to the cross, lest the hands should be torn from the nails. They then fastened His left foot on to His right foot, having first bored a hole through them with a species of piercer, because they could not be placed in such a position as to be nailed together at once. Next they took a very long nail and drove it completely through both feet into the cross below, which operation was more than usually painful, on account of His body being so unnaturally stretched out; I counted at least thirty-six blows of the hammer. During the whole time of the crucifixion Our Lord never ceased praying, and repeating those passages in the Psalms, which He was then accompanying, although, from time to time a feeble moan, caused by excess of suffering, might be heard. In this manner He had prayed when carrying His cross, and thus He continued to pray until His death. I heard Him repeat all these prophecies; I repeated them after Him, and I have often since noted the different passages when reading the Psalms, but I now feel so exhausted with grief that I cannot at all connect them. When the crucifixion of Jesus was finished, the commander of the Roman soldiers ordered Pilate's inscription to be nailed on the top of the cross. The Pharisees were much incensed at this, and their anger was increased by the jeers of the Roman soldiers, who pointed at their crucified King; they therefore hastened back to Jerusalem, determined to use their best endeavors to persuade the governor to allow them to substitute another inscription. It was about a quarter past twelve when Jesus was crucified; and at the moment the cross was lifted up, the Temple resounded with the blast of trumpets, which were always blown to announce the sacrifice of the Paschal Lamb. MEDITATION From among the many aspects of the Eleventh Station that might be dwelt upon, only two are to be considered here: first, the implication of finality contained in the idea of nailing; second, the nature of the cross to which the modern Christian who is in earnest about his religion must expect to be nailed. That perseverance, or at least consistency of vision and thought, will come into the treatment of both aspects is obvious. Without the assumption of perseverance, there would he little point in dealing with, or even practicing, any virtue. Here it acts as a backdrop against which the twofold theme is played out on the platform of daily experience. Few would deny, then, that one of the chief weaknesses of our time is the spirit of experimentalism. People try a thing, and if it does not immediately answer to their need, they try something else; they do not want to be tied down. The desire to leave open a loophole of escape prompts the desire to escape, and life becomes a series of temporary ventures prematurely abandoned. Men and women are becoming increasingly reluctant to commit themselves: whether it is a question of a policy or a philosophy, a religious system or a career, the modern psyche claims the right to reverse its pledges at a moment’s notice and to redirect itself along unexplored avenues of possibility. So marriage becomes an adventure that is well worth trying; if the current partner turns out to be unsatisfactory, the sensible thing to do is to make a change. A chosen occupation becomes a trial employment of faculties that are always on the lookout for something else. Whereas, in other times, a man looked forward in his undertakings to striking roots, the modern man looks forward to pulling them up. A man today will think little of changing his job, his house, his son’s school, his religion, his political allegiance, his car, and his wife — perhaps all in one year. The present-day dislike of being pinned down shows itself unmistakably in the matter of modern entertainment: people prefer to come in and go out when they like, and so choose the continuous performance of a film rather than the single performance of a play. They prefer to hear a concert that they can switch off to the one that commands a set attendance. They would rather eat and drink informally and standing up, because to sit between two people at a dinner party would rule out the possibility of escape. They want to do their traveling by car, because it avoids being committed to the times of trains. They read digests, because they cannot face the ordeal of pursuing the whole book to the end. Always an unwillingness to go the whole way, to be bound to a course. Against this we have Christ allowing Himself to be nailed to the Cross. He could have backed out, even then, but He did not. He was preaching a doctrine of stability, of completeness. The refusal to call the whole thing off may be called obstinacy by those whose purpose is flexible, but it represents an attitude much in evidence among the saints. If today people are slightly scornful of the stable man, charging him with a lack of imagination and initiative, it is because they are losing the sense of tradition — particularly of Christian Tradition. The man who is stable will always be useful to his contemporaries in pretty well any society, but will he be held up by them as an example to be followed? Man tends to discredit the things he is bad at and to canonize those which come easily to him. The urge to alter our lives every few years may well be hailed by future psychologists as a sign of health; steadfastness — Is there already a faintly old-fashioned ring to the word? — will be at a discount. Fortunately, there will always be the vows of religion to attract the world’s attention to the essentially connected ideals of immolation and permanence — ideals implied particularly by the Eleventh Station of the Cross. Then comes the kind of cross to which our century is nailed. For having so long evaded the Cross, padding it out with cotton wool, man is paying the penalty of being stretched upon a cross whose existence the world does not recognize. Once the reality of sin is denied, the Cross, which is the consequence of sin, has equally to be denied. Having done away with man’s moral responsibility, the world quite logically does away with the idea of Christ’s divine responsibility: the act of expiation becomes unnecessary, and the Cross is made void. But although the Cross, as a Christian reality and in terms of atonement, is repudiated, human suffering goes on. Pain is with us still, and although its existence is as freely admitted as ever — and indeed attended to as never before — it is attributed to causes unconnected with the Fall, is subjected to investigations unconnected with the Redemption, is given hope of relief unconnected with the Resurrection. Abandon the Christian concept of suffering as a mixture of punishment and opportunity, and you are reduced to proposing new explanations of human tendencies, new remedies for human ills. When acts that used to he expected to rouse a sense of guilt are accounted for by inherited compulsions, by immaturity, by environment, the sufferer who used to merit the reward of cross-bearing has to be content with being labeled an arrested affectionate, socially starved, a victim of under-privilege, a case of abnormal mental sensitivity. Our troubles can be sympathized with because they relate to melancholy or fear or anxiety about money, but they may not be seen in the context of Christ’s Cross. We are nailed, inescapably, to a sacrificial wood that knows no sacrifice, to an altar whose foundations are buried, not in the common clay of our formation, but in the unmined depths of our subconscious. The trouble with tinkering with the subconscious is that, in getting down into it, all sorts of controls have to be released that are uncommonly difficult to regain when the investigations and adjustments are over. And this is not only a matter affecting self-discipline; it is also a matter affecting faith. Consent given to the process that proposes the removal of compulsions and inhibitions may well prove to be a consent that removes other things besides — a case of taking off the head while taking off the hat, of throwing away the baby with the bath water. Morals, faith, and spirituality go together, and in order to recognize the Cross for what it is, and, still more, to profit by it, there is need of all three. Determination to endure is not enough, and any system or science that leaves out of account any one part of the essential Christian ideal is bound to fall short of the truth. Certainly the man who is led to believe that God is a father-image, that Hell is a fear reflex, that the Church has arisen out of civilization’s Oedipus complex, that a religious vocation is the result of an Electra projection, will not readily take to the idea that the Cross of Christ is the instrument of man’s salvation. It needs faith to see the sense of suffering, and it needs at least a measure of spirituality to accept it personally as something sanctifying. To imagine that a man can reach the state of perfect well-being by a process of eliminating, one by one, the causes of his inner conflict is only less unlikely than to imagine that he can do so without God. Man is a center of conflict, and the conflict is the Cross. The more he tries to evade the conflict, the more he lays himself open to further conflicts and further crosses. In his preoccupation about ridding himself of the causes of conflict, he becomes subject to dread and doubt: he fears the outcome of the search. His dread of suffering will be his suffering; his feverish avoidance of the Cross will be his cross — a cross that, as such, he refuses to acknowledge. Whereas, to a Christian, the element of fear is an accepted element of the Cross, to the man who rationalizes every instinct from conscience onward, fear is just another one of nature’s flaws — like loneliness and depression, jealousy and discouragement, and all the other horrors to which man is liable — and must be made good by the judicious study of the mind. Against all this business of rationalization, we have the Passion telling us what is true suffering: pain and fear of more pain. The Cross is the Cross, and there is no substitute for it. Christ not only took it up for our sakes, but for our sakes was nailed down upon it. CONCLUDING PRAYER V. We adore Thee, O Christ, and we praise Thee, R.. Because by Thy holy cross Thou hast redeemed the world. O Jesus, strip me of my old sinful self and renew me and rebuild me according to Thy will and desire. I will not spare myself, however painful this should be for me: stripped of all temporal and material things, stripped of my attachments to the persons, places and things of this world; stripped of my own will and preferences; I wish to die to all these, in order to live for Thee forever. PRAYER O Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me! Offer me Thy helping hand, and aid me, that I may not fall again into my former sins. From this very moment, I will earnestly strive to reform: nevermore will I sin! Thou, O sole support of the weak, by Thy grace, without which I can do nothing, strengthen me to carry out faithfully this my resolution. Our Father Hail Mary. Glory Be. V. Lord Jesus, crucified, R. Have mercy on us! |

Web Hosting by Just Host