| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE NAME OF THE SAINT YOU WISH TO VIEW

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

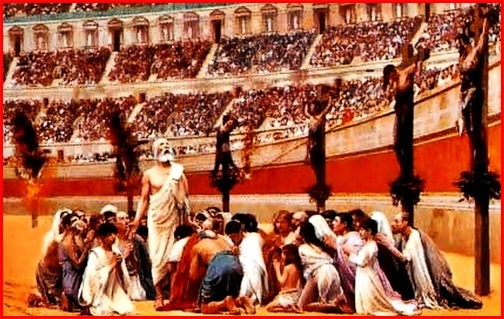

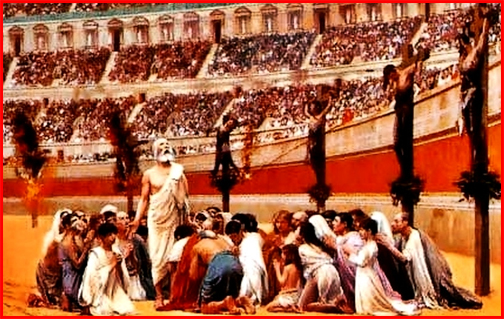

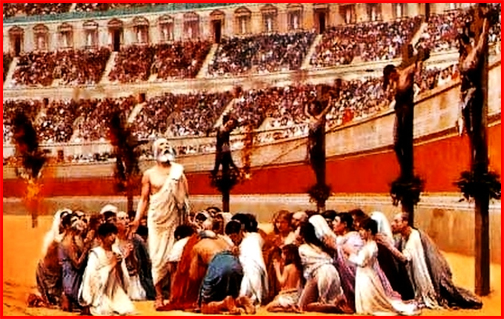

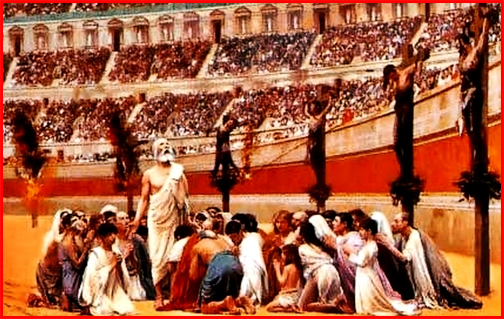

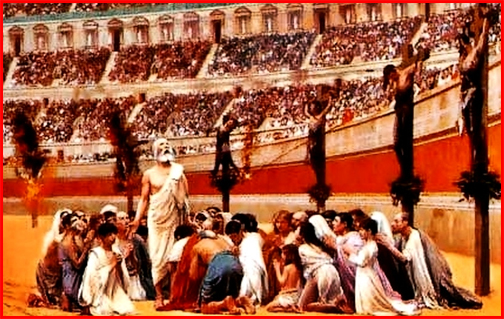

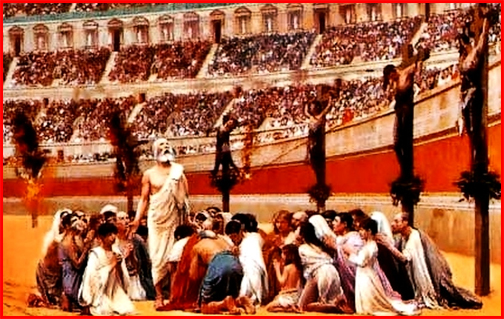

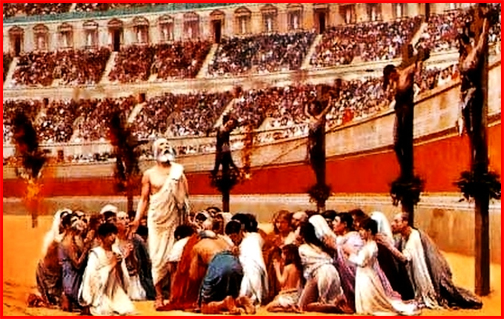

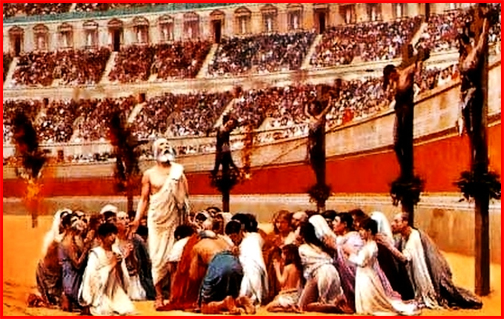

Let us not think martyrdom to be a thing of the past. The 20th century saw more people killed for the Faith than any other century in the history of the Church. The 21st century is likely to surpass the 20th century in its numbers of martyrs. Our Lady of Good Success said: "The small number of souls, who hidden, will preserve the treasures of the Faith and practice virtue will suffer a cruel, unspeakable and prolonged martyrdom. Many will succumb to death from the violence of their sufferings and those who sacrifice themselves for the Church and their country will be counted as martyrs." Our Lady of Fatima also indicated that "Russia will spread her errors throughout the world, causing wars and persecutions of the Church. The good will be martyred."

Martyrdom, for many, is not what they wanted for Christmas — yet, speaking of Christmas, we are reminded of the martyrdom of the Holy Innocents — babies who were not pining for, nor expecting death to come their way. This tragic, yet glorious event, shows us that martyrdom spares nobody — not even babies! Throughout history there has been a constant procession of martyrs—babies, children, women and men, laity and religious — who have witnessed and died for Christ. Martyrdom is not a thing of the past—it is a thing of the near future. It behooves us to think about it, understand it, and prepare for it — even if we may not want it or fear it. These articles — in the School of Martyrdom — will seek to do that. Their purpose and goal will be help us remove some of that trepidation and fear by passing a constant stream of heroes of Christ before our eyes — children, women and men, from all walks of life, from all centuries — who will give us not only an example of how to witness to Christ and our Faith, but also accustom us to looking at martyrdom from a new perspective and with a new attitude.

Martyrdom, for many, is not what they wanted for Christmas — yet, speaking of Christmas, we are reminded of the martyrdom of the Holy Innocents — babies who were not pining for, nor expecting death to come their way. This tragic, yet glorious event, shows us that martyrdom spares nobody — not even babies! Throughout history there has been a constant procession of martyrs—babies, children, women and men, laity and religious — who have witnessed and died for Christ. Martyrdom is not a thing of the past—it is a thing of the near future. It behooves us to think about it, understand it, and prepare for it — even if we may not want it or fear it. These articles — in the School of Martyrdom — will seek to do that. Their purpose and goal will be help us remove some of that trepidation and fear by passing a constant stream of heroes of Christ before our eyes — children, women and men, from all walks of life, from all centuries — who will give us not only an example of how to witness to Christ and our Faith, but also accustom us to looking at martyrdom from a new perspective and with a new attitude.

ARTICLE 1

OPENING THOUGHTS ON MARTYRDOM

OPENING THOUGHTS ON MARTYRDOM

|

|

In a culture that emphasizes the preservation of youth and bodily life, the concept of martyrdom does seem foreign—in fact, for some, it seems to be insane and radical. Martyrdom according to the Catechism is “the supreme witness given to the truth of the Faith: it means bearing witness even unto death.” Rather than renounce his Faith, the martyr bears witness with extraordinary fortitude to the belief that Christ suffered, died, and rose from the dead for our salvation, and to the truths of our Catholic Faith. The word martyr itself means “witness.”

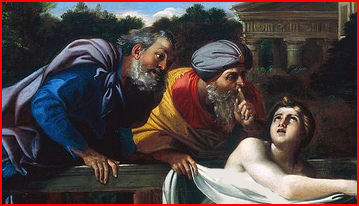

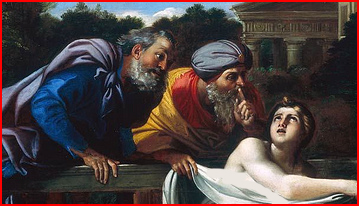

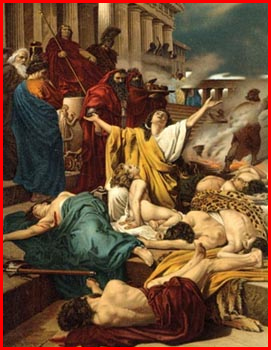

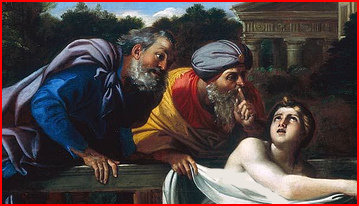

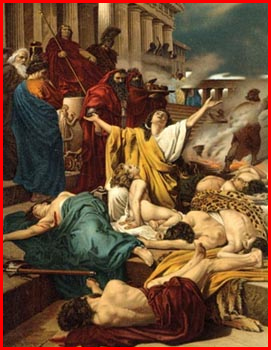

Sacred Scripture attests to the courage of men and women who were willing to die as martyrs rather than renounce their Faith or be unfaithful to God’s law by sinning. In the Old Testament, Susanna preferred to die rather than yield to the sinful passions of the two unjust judges (Daniel 13). Again, in the Old Testament, the Machabees laid down their lives rather than lay down their religion. St. John the Baptist refused to compromise with evil and never ceased professing the law of God; in the end he “gave his life in witness to truth and justice” (Opening Prayer for the Feast of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist). St. Stephen, one of the first deacons of the Church, was also the first martyr (Act 6:8 ff), followed by the Apostle St. James the Greater (Acts 12:2). The witness of these martyrs dovetails in the apocalyptic vision of the Book of the Apocalypse. Here, St. John saw the angels and saints from every nation and race, people and tongue, standing before the throne and the Lamb. They cried out, “Salvation is from our God, who is seated on the throne, and from the Lamb!” When asked who they were, the answer came, “These are the ones who have survived the great period of trial; they have washed their robes and made them white in the blood of the Lamb.” (Apocalypse 7:9-17.) The spiritual rationale which underpins the act of martyrdom is one that each Christian must accept. In teaching the conditions for true discipleship, our Lord asserted, “If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me. For he that will save his life, shall lose it: and he that shall lose his life for my sake, shall find it. For what doth it profit a man, if he gain the whole world, and suffer the loss of his own soul? Or what exchange shall a man give for his soul?” (Matthew 16:24-26). Yes, the Christian must be prepared to bear the cross of Our Lord, even if it means forsaking life in this world. In doing so, however, such a Christian will be blessed in the eyes of God. In the Beatitudes, those right attitudes of living that bring blessed union with God, the eighth beatitude is repeated: “Blessed are they that suffer persecution for justice sake: for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven” (Matthew 5:10). Moreover, Jesus personalized this beatitude: “Blessed are ye when they shall revile you, and persecute you, and speak all that is evil against you, untruly, for My sake” (Matthew 5:11). Nevertheless, the point is not just the suffering here and now for the faith, but the courageous perseverance which gives way to everlasting life: “Be glad and rejoice, for your reward is very great in heaven. For so they persecuted the prophets that were before you” (Matthew 5:12.) This spiritual rationale is reflected beautifully in the testimony of the martyrs of our early Church during the time of Roman persecution. For example, St. Ignatius of Antioch (d. 110), who was the third bishop of Antioch following St. Evodius (who had succeeded St. Peter the Apostle), and who had been a student of St. John the Apostle, was condemned by the Emperor Trajan and sentenced to being devoured by beasts in the arena. On the way to Rome where he would die, he wrote seven letters, including one to the Romans, in which he reflected on his pending death: “Allow me to be eaten by the beasts, which are my way of reaching God. I am God’s wheat, and I am to be ground by the teeth of wild beasts, so that I may become the pure bread of Christ,” and later “Neither the pleasures of the world nor the kingdoms of this age will be of any use to me. It is better for me to die in order to unite myself to Christ Jesus than to reign over the ends of the earth. I seek Him who died for us; I desire Him who rose for us. My birth is approaching…” (Letter to the Romans). Another great witness to the faith during this time was St. Polycarp, the Bishop of Smyrna, who was a friend of St. Ignatius and who had also been a student of St. John the Apostle and had been consecrated a bishop by him. For refusing to offer sacrifice to the Roman gods and to acknowledge the divinity of the Emperor, St. Polycarp was condemned to death by burning at the stake at the age of eighty-six during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. As the pyre was about to be lit, St. Polycarp prayed, “I bless you for having judged me worthy from this day and this hour to be counted among your martyrs…. You have kept your promise, God of faithfulness and truth. For this reason and for everything, I praise you, I bless you, I glorify you, through the eternal and heavenly High Priest, Jesus Christ, your beloved Son. Through Him, who is with you and the Holy Spirit, may glory be given to you, now and in the ages to come. Amen.” (The Martyrdom of St. Polycarp). In defense of the martyrs, Tertullian (d. 250) later wrote in his Apology, “Crucify us, torture us, condemn us, destroy us! Your wickedness is the proof of our innocence, for which reason does God suffer us to suffer this. When recently you condemned a Christian maiden to a panderer rather than to a panther, you realized and confessed openly that with us a stain on our purity is regarded as more dreadful than any punishment and worse than death. Nor does your cruelty, however exquisite, accomplish anything: rather, it is an enticement to our religion. The more we are hewn down by you, the more numerous do we become. The blood of martyrs is the seed of Christians!” Without question, despite the worst persecutions, the Church has continued to survive and to grow, due greatly to the courageous witness and prayers of the holy martyrs. |

ARTICLE 2

LEARNING FROM ST. CYPRIAN'S MARTYRDOM

LEARNING FROM ST. CYPRIAN'S MARTYRDOM

|

|

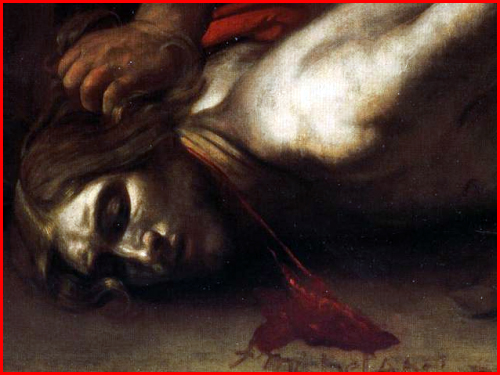

Here is an eyewitness account of St. Cyprian’s martyrdom, A.D. 258, in Carthage, near modern Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, North Africa:

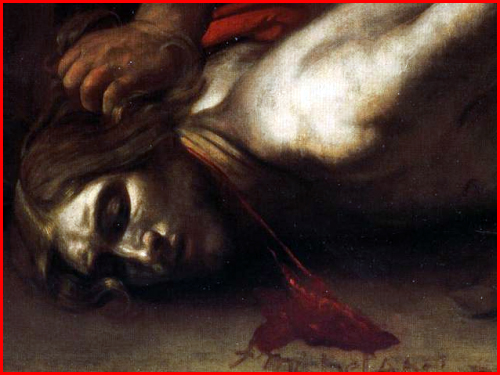

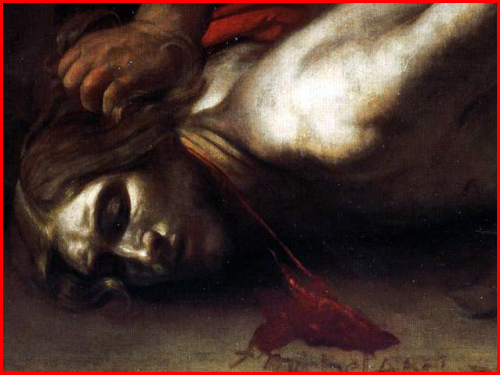

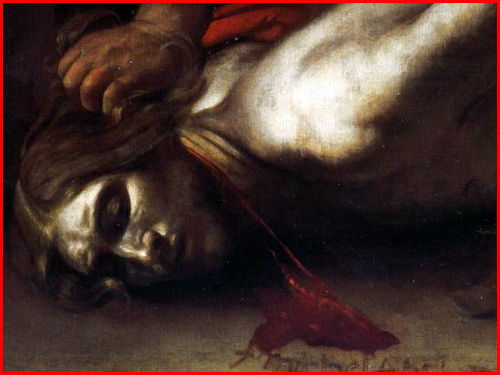

The next day, September 14th, a great crowd gathered early in the morning near the Villa Sexti at the command of the proconsul, Galerius Maximus. Then the same proconsul, Galerius Maximus, ordered that Cyprian be brought to him that very day as he was sitting in the atrium at the Sauciolum. When he had been brought forward, the proconsul Galerius Maximus said to the bishop Cyprian, “Are you Thascius, known also as Cyprian?” The bishop Cyprian responded, “I am.” The proconsul Galerius Maximus said, “Have you presented yourself to people as the head of a sacrilegious movement?” The bishop Cyprian responded, “I have.” The proconsul Galerius Maximus said, “The most sacred emperors have ordered you to offer worship.” The bishop Cyprian said, “I will not.” Galerius Maximus said, “Have a care for your own interests.” The bishop Cyprian responded, “In so just a matter there need be no reflection.” After he had spoken with his council, Galerius Maximus hesitatingly and unwillingly pronounced the sentence in words of this sort: “You have lived for a long time in a sacrilegious frame of mind, have gathered very many other members of this impious conspiracy around you and have set yourself up as an enemy of the Roman gods and their sacred rites. Our pious and most sacred princes, the august Valerian and Gallienus and our most noble Caesar, Valerian, have not been able to call you back to the observance of their worship. Therefore, since you are the author and admitted leader of the most worthless crimes, you will yourself be a warning for these people whom you have gathered around you in your crime. Respect for the law will be confirmed by your blood.” Once he had said this, he read out the sentence from the tablet: “It has been decided that Thascius Cyprian is to be executed by the sword.” The bishop Cyprian said, “Thanks be to God.” After this sentence, the crowd of the brethren said, “Let us also be beheaded with him.” On this account a great commotion broke out among the brethren and a large crowd followed him. Cyprian was led into the field of Sextus. There he took off his mantle and hood, knelt down on the ground and prostrated himself in prayer to the Lord. When he had taken off his dalmatic and given it to the deacons, he stood erect and awaited the executioner. When the executioner came, Cyprian ordered his attendants to give the executioner twenty-five gold coins. Linen cloths and handkerchiefs were spread out in front of him by the brethren [Note: to collect the blood, as the relic of a martyr]. After that, blessed Cyprian put on the blindfold with his own hands, but since he was not able to tie the ends by himself, the priest Julianus and the subdeacon Julianus tied them for him. In this manner the blessed Cyprian suffered death and his body was laid in a place nearby on account of the curiosity of the pagans. Then it was taken up at night with candles and torches and brought with prayer and great triumph to the cemetery of the procurator Macrobius Candidianus, which is near the pools. After a few days the proconsul Galerius Maximus died. The most blessed martyr Cyprian suffered on the fourteenth of September under the emperors Valerian and Gallienus, but in the reign of Our Lord Jesus Christ, to Whom is honor and glory forever and ever. Amen.” We note three elements of his martyrdom: (1) he was put to death, (2) for Christ: for the Faith, for refusing to apostatize and offer false worship, etc., and (3) we see the Christian joy and gladness to die for Christ’s sake. The true approach to martyrdom is to see it as a triumph. So the early Christians rejoiced when one of their number was faithful unto death. Similarly, during the persecutions of the 16-17th century, seminarians at the English College, Rome, used to gather at the foot of the chapel’s painting of the Holy Trinity to sing a Te Deum whenever news arrived that a former student had been put to death for the Faith. It is a victory over the world, the flesh and the devil — everything that opposes your Christian life. It is the greatest way to die; it is the highest form of Christian death. |

ARTICLE 3

WHEN IS A MARTYR NOT A MARTYR?

WHEN IS A MARTYR NOT A MARTYR?

|

|

The great moral theologian, Fr. Dominic Prummer O.P., says:

“Acts of Fortitude. . . . these acts reach their peak in martyrdom. Martyrdom is the endurance of bodily death in witness to the Christian religion. Therefore three conditions must be verified for martyrdom: a) actual death; (b) the infliction of death by an enemy out of hatred for Christianity; (c) the voluntary acceptance of death. — Therefore the following are not genuinely martyrs: those who die by contracting disease in their care of lepers, those who suffer death for natural truths or for heresy, or who [indirectly] bring about their own death to safeguard their person. — The effect of martyrdom is the remission of all sin and punishment, since it is an act of perfect charity. According to Christian doctrine, martyrdom renders the soul of the martyr worthy of immediate entrance into Heaven. The Church prays to the martyrs, but has never prayed for the martyrs.” Likewise, the Dominican Fr. Benedict Ashley says: “True martyrdom requires three conditions: (1) that the victim actually die, (2) that he or she dies in witness of Faith in Christ which is directly expressed in words, or implicitly in acts done or sins refused because of Faith, and (3) that the victim accepts death voluntarily. They are not martyrs who do not actually die, or die from disease, for the sake of merely natural truths, or heresy, or for their country in war, or through suicide, etc.” Fr Ashley explains: “‘Martyr’ is often used loosely of anyone who dies for the sake of any cause. But the Christian cause is in fact objectively true, and not a subjective illusion, as are many of the causes for which persons die sincerely but deludedly. Thus those who die for the sake of fanatical religious cults, or as terrorists, or for their own glory, however sincere, are not genuine martyrs, but are objectively suicides. Nor are those who die for a noble but merely human motive, as the parent who dies to save a child, or a soldier for his country, since such virtuous acts can pertain simply to the order of natural virtue. In 2004, the Pope canonized Gianna Beretta Molla, an Italian mother. During her pregnancy with her fourth child, she was diagnosed with a large ovarian cyst. Her surgeon recommended an abortion in order to save Gianna’s life. She refused that, of course, and refused any operation, since that would threaten the life of her baby. So she died a week after childbirth, in 1962, at the age of 39, heroically caring more for her unborn child than for her own life. Today that child is a physician herself, and involved in the pro-life movement in Italy. Her mother is not a martyr, but a hero of love, and her mother’s sacrifice brought forth a harvest. “The sacred name of martyr belongs only to one who renders testimony to divine truth. A heretic in good faith, who dies for Christ, may be counted among the martyrs, but a contumacious heretic, who dies for his sect, is not a martyr, because he does not testify to divine truth, but to a (false) human teaching.” Blessed Damien of Molokai is a hero (of charity), but not a martyr. St. Pio of Pietrelcina suffered enormously over 50 years with the stigmata, but is not a martyr. In the Missal, a saint who is a martyr is always named such. M. is placed next to their name for Martyr. We count as an exception the Holy Innocents, whom the Church, although they lack the usual element of acceptance of death, nevertheless honors as martyrs in the liturgy, because they died in the place of the infant Christ and received the Baptism of Blood. Abortion victims cannot be counted as martyrs; they are victims, but not martyrs. There is a movement, originating in Surbiton, London, to get them officially canonized — but this is a mistake. If they are martyrs, then every murder victim dying in a state of grace would be a martyr. This is seen to be false from the investigation the Church conducts into a claimed martyr. For a claimed martyr, the object of the initial diocesan inquiry is threefold: (a) the candidate’s life (b) martyrdom (c) reputation for martyrdom. The crucial question to establish martyrdom is: Was this person killed for the Faith? Not simply: Was he murdered? — which is usually obvious. Death itself might not occur immediately, but if the sufferings inflicted lead to death within a reasonable time, then that will count as martyrdom. In English law, it has been the practice to deem an act “murder” (or manslaughter) if death comes within a year and a day from the injury inflicted. The Church has always held that martyrdom is equivalent to Baptism for those not yet baptized. Baptism of Blood is the name given to this. It is Catholic doctrine that the Baptism of Blood blots out Original Sin, and all actual sin, together with the punishment due to it. This is evident from the words of Christ: He has absolutely promised salvation to those who give their lives for the Gospel: “He who loses his life for My sake will find it”; and again He says, “So everyone who acknowledges Me before men, I also will acknowledge before My Father Who is in Heaven”. Moreover, from the Tradition of the Church: the Church honors as martyrs in Heaven several who were never baptised: the Holy Innocents massacred by Herod; St. Emerentiana (c. 304); one of the 22 Ugandan martyrs, St. Mukasa Kiriwawanvu, who was still a catechumen. St. Augustine says, “it would be an affront to pray for a martyr: we should rather commend ourselves to his prayers.” (Sermon 159) “Today the term ‘martyr’ is applied very freely to all sorts of people; for example, the Japanese kamikaze pilots, the Buddhists who burnt themselves as a protest to communism, and the Shiite soldiers in the Iran-Iraq war are all called ‘martyrs’. But this most honourable title, which means ‘witness’ has a specifically Jewish and Christian meaning.” The Blessed Virgin Mary, since she surpassed the martyrs in her sorrows, is called Queen of Martyrs, but strictly speaking she was not a martyr, since she did not die from her sorrows. |

ARTICLE 4

WITNESS AND MARTYRDOM IN THE BIBLE

WITNESS AND MARTYRDOM IN THE BIBLE

|

|

The mission of Jesus was too difficult and too great to be accomplished by simple force. It had to be accomplished through the much harder way of courageous suffering and dying in witness of the truth. Hence the New Testament model is not the warrior but the martyr, of which Jesus on the Cross is the supreme example, accompanied by his mother Mary, her heart pierced spiritually by the same lance that pierced the heart of her Son (cf. Luke 2:34-35).

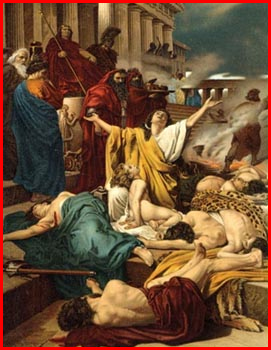

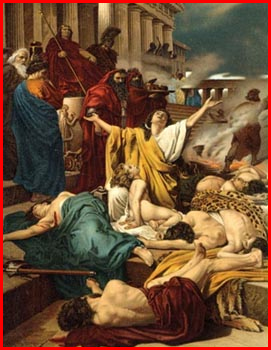

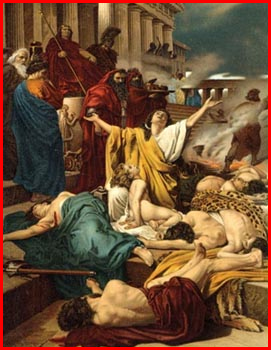

The strict concept of martyrdom is first clearly stated in the Bible in the story of the seven brothers and their mother (2 Machabees, chapter 7) who died rather than eat pork which the Greek oppressors tried to force upon them to indicate their renunciation of the law and the covenant with God. But, in the same persecution, Judas Maccabeus was not a martyr — although he died fighting for the Jewish Law — because he died fighting, not as one submitting to being killed. Jesus Himself prophetically exhorted His disciples to be the witnesses of His life and His words. He even predicted in detail their lot: they will be chased from the Synagogue, betrayed by their own relatives, accused and hauled before kings and governors, and put to death for His Name (Matthew 10:17, 24; Luke 21:12). The first Christian martyr after Jesus Himself was St. Stephen, stoned to death in Jerusalem for preaching the Gospel. As they were stoning Stephen, he called out, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.” Then he fell to his knees and cried out in a loud voice, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them!” And when he said this, he fell asleep (Acts 7:59-60). Even during Our Lord’s Public Ministry, St. John the Baptist died a martyr’s death, in witness to the law of God regarding marriage. Thus the Christian martyr does not die out of hatred of the enemy as a soldier might, but out of love for his killers, as Jesus taught and lived (Matthew 5:43-48). “No man has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:13), but for the Christian our enemies are also our friends as long as their conversion is possible. After Stephen: St. Peter, St. Paul, and St. James the Apostle (Acts 12:2) were all martyrs, and following them a “great cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12:1). In the liturgy of the Church, special honor is given to the Virgin Martyrs (women and men, Apocalypse 14:4) who are models of both the virtues of chastity and courage. Christians who do not die for the Faith, may yet share in martyrdom, as the Virgin Mary did, by being ready to die for it. Christians are engaged in a spiritual warfare: “Put on the whole armor of God, that you may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil. For we are not contending against flesh and blood, but against the principalities, against the powers, against the world rulers of this present darkness, against the spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places. Therefore take the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand” (Ephesians 6:11-13) “Be sober, be watchful. Your adversary the devil prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour. Resist him, firm in your Faith, knowing that the same experience of suffering is required of your brotherhood throughout the world” (1 Peter 5:8-9). |

ARTICLE 5

MARTYRDOM IN THE EARLY CHURCH

MARTYRDOM IN THE EARLY CHURCH

|

|

The Greek word martus signifies a witness who testifies to a fact of which he has knowledge from personal observation. It is in this sense that the term first appears in Christian literature; the Apostles were “witnesses” of all that they had observed in the public life of Christ, as well as of all they had learned from His teaching, “in Jerusalem, and in all Judea, and Samaria, and even to the uttermost part of the Earth” (Acts 1:8).

St. Peter, in his address to the Apostles and disciples relative to the election of a successor to Judas, employs the term with this meaning: “Wherefore, of these men who have accompanied with us all the time that the Lord Jesus came in and went out among us, beginning from the baptism of John until the day he was taken up from us, one of these must be made witness with us of his resurrection” (Acts 1:22). In his first public speech, the chief of the Apostles, Peter, speaks of himself and his companions as “witnesses” who saw the risen Christ and subsequently, after the miraculous escape of the Apostles from prison, when brought a second time before the tribunal, Peter again alludes to the twelve as witnesses to Christ, as the Prince and Savior of Israel, Who rose from the dead; and added that in giving their public testimony to the facts, of which they were certain, they must obey God rather than man (Acts 5:29 sqq.). In his First Epistle St. Peter also refers to himself as a “witness of the sufferings of Christ” (1 Peter 5:1). But even in these first examples of the use of the word martus in Christian terminology a new shade of meaning is already noticeable, in addition to the accepted signification of the term. The disciples of Christ were no ordinary witnesses, such as those who gave testimony in a court of justice. These kinds of witnesses ran no risk in bearing testimony to facts they knew or had observed―whereas the witnesses of Christ were brought face-to-face daily, from the beginning of their apostolate, with the possibility of incurring severe punishment and even death itself simply for being Christians. Thus, St. Stephen was a witness who, early in the history of Christianity, sealed his testimony with his blood. The careers of the Apostles were at all times filled with dangers of the gravest kind, until eventually they all suffered the last penalty for their convictions―death. Thus, within the lifetime of the Apostles, the term martus came to be used in the sense of a witness who at any time might be called upon to deny what he testified to, under penalty of death. A martyr, or witness of Christ, is a person who―even though he has never seen nor heard Christ, the Divine Founder of the Church―is nevertheless so firmly convinced of the truths of the Christian religion, that he gladly suffers death rather than deny it. St. John, at the end of the first century, employs the word with this meaning; Antipas, a convert from paganism, is spoken of as a “faithful witness (martus) who was slain among you, where Satan dwelleth” (Apocalypse 2:13). Further on the same Apostle speaks of the “souls of them that were slain for the Word of God and for the testimony (martyrian) which they held” (Apocalypse 6:9). Yet, it was only by degrees, in the course of the first age of the Church, that the term martyr came to be exclusively applied to those who had died for the Faith. The grandsons of St. Jude, for example, on their escape from the peril they underwent when cited before Domitian were afterwards regarded as martyrs. The famous confessors of Lyons, who endured so bravely awful tortures for their belief, were looked upon by their fellow-Christians as martyrs, but they themselves declined this title as of right belonging only to those who had actually died: “They are already martyrs whom Christ has deemed worthy to be taken up in their confession, having sealed their testimony by their departure; but we are confessors mean and lowly.” This distinction between martyrs and confessors is thus traceable to the latter part of the second century―those only were martyrs who had suffered the extreme penalty of death, whereas the title of confessors was given to Christians who had shown their willingness to die for their belief, by bravely enduring imprisonment or torture, but were not actually put to death. Yet the term “martyr” was still sometimes applied during the third century to persons still living, as, for instance, by St. Cyprian, who gave the title of martyrs to a number of bishops, priests, and laymen condemned to penal servitude in the mines. Tertullian speaks of those arrested as Christians and not yet condemned as martyres designate (designated for martyrdom). In the fourth century, St. Gregory of Nazianzus alludes to St. Basil as “a martyr”, but evidently employs the term in the broad sense in which the word is still sometimes applied to a person who has borne many and grave hardships in the cause of Christianity. The description of a martyr given by the pagan historian Ammianus Marcellinus (XXII, xvii), shows that by the middle of the fourth century the title was everywhere reserved to those who had actually suffered death for their Faith. Heretics and schismatics put to death as Christians were denied the title of martyrs―as stated by St. Cyprian, Treatise on Unity 14; St. Augustine, Ep. 173; Eusebius, Church History, vol. 16, vol. 21. St. Cyprian lays down clearly the general principle that “he cannot be a martyr who is not in the Church; he cannot attain unto the kingdom who forsakes that which shall reign there.” St. Clement of Alexandria strongly disapproves of some heretics who gave themselves up to the law; he said that they “banish themselves without being martyrs.” The orthodox were not permitted to seek martyrdom. Tertullian, however, approves the conduct of the Christians of a province of Asia who gave themselves up to the governor, Arrius Antoninus (Ad. Scap., v). Eusebius also relates with approval the incident of three Christians of Cæsarea in Palestine who, in the persecution of Valerian, presented themselves to the judge and were condemned to death (Church History VII.12). But while circumstances might sometimes excuse such a course, it was generally held to be imprudent. St. Gregory of Nazianzus sums up in a sentence the rule to be followed in such cases: it is mere rashness to seek death, but it is cowardly to refuse it (Orat. xlii, 5, 6). The example of a Christian of Smyrna named Quintus, who, in the time of St. Polycarp, persuaded several of his fellow believers to declare themselves Christians, was a warning of what might happen to the over-zealous: Quintus at the last moment apostatized, though his companions persevered. Breaking idols was condemned by the Council of Elvira (306), which, in its sixtieth canon, decreed that a Christian put to death for such vandalism, would not be enrolled as a martyr. Lactantius, on the other hand, has only mild censure for a Christian of Nicomedia who suffered martyrdom for tearing down the edict of persecution (Do mort. pers., xiii). In one case St. Cyprian authorizes seeking martyrdom. Writing to his priests and deacons regarding repentant lapsi who were clamoring to be received back into communion, the bishop after giving general directions on the subject, concludes by saying that if these impatient personages are so eager to get back to the Church there is a way of doing so open to them. “The struggle is still going forward”, he says, “and the strife is waged daily. If they (the lapsi) truly and with constancy repent of what they have done, and the fervor of their Faith prevails, he who cannot be delayed may be crowned” (Ep. xiii). |

ARTICLE 6

THE REASONS BEHIND THE PERSECUTION OF EARLY CHRISTIANS

Part 1 of 2

THE REASONS BEHIND THE PERSECUTION OF EARLY CHRISTIANS

Part 1 of 2

|

|

Acceptance of the national religion in antiquity was an obligation incumbent on all citizens―failure to worship the gods of the State was equivalent to treason. This universally accepted principle is responsible for the various persecutions suffered by Christians before the reign of Constantine. Christians denied the existence of the gods of the state pantheon and therefore refused to worship them. As a consequence, they were regarded as atheists.

The Jews also rejected the gods of Rome, and yet escaped persecution. But the Jews, from the Roman standpoint, had a national religion and a national God, Jehovah, whom they had a full legal right to worship. Even after the destruction of Jerusalem, when the Jews ceased to exist as a nation, Vespasian made no change in their religious status, except that the tribute [monetary donation], formerly paid by Jews to their Temple at Jerusalem, was henceforth to be paid to the Roman treasury. For some time after its establishment, the Christian Church enjoyed the religious privileges of the Jewish nation, but since the chiefs of the Jewish religion were against Christianity, they did not permit this equal footing of Christianity with Judaism for very long permit and soon protested about this state of things. For they detested Christ’s religion as much as they detested Christ Himself. At what date the Roman authorities had their attention directed to the difference between the Jewish and the Christian religion cannot be determined, but it appears to be fairly well established that laws forbidding Christianity were enacted before the end of the first century. Tertullian is authority for the statement that persecution of the Christians was institutum Neronianum — an institution of Nero — (Ad nat., i, 7). The First Epistle of St. Peter also clearly alludes to the prohibition of Christianity and Christians, at the time it was written: “A Christian, let him not be ashamed, but let him glorify God in that name” (1 Peter 4:16). The Roman Emperor Domitian (reigned 81-96 AD), is also known to have punished Christian members of his own family with death on the charge of being guilty of atheism. While it is therefore probable that the formula: “Let there be no Christians” (Christiani non sint) dates from the second half of the first century, the earliest such attitude on subject of Christianity is that of the Emperor Trajan (98-117) in his famous letter to the younger Pliny, his legate in Bithynia. Pliny―a legate and an army commander―had been sent from Rome, by the emperor, to restore order in the Province of Bithynia-Pontus. Among the difficulties he encountered in the execution of his commission one of the most serious concerned the Christians. The extraordinarily large number of Christians he found within his jurisdiction greatly surprised him. The contagion of their “superstition”, he reported to Trajan, affected not only the cities, but even the villages and country districts of the province. One consequence of the general defection from the pagan state religion was of an economic order―so many people had become Christians that purchasers were no longer found for the victims that once in great numbers were offered to the gods. Complaints were laid before the legate relative to this state of affairs, with the result that some Christians were arrested and brought before Pliny for examination. The suspects were interrogated as to their beliefs and those of them who persisted in declining repeated invitations to give up their Christian beliefs, were executed. Some of the prisoners, however, after first affirming that they were Christians, afterwards, when threatened with punishment, qualified their first admission by saying that at one time they had been followers of Christianity, but were so no longer. Others again denied that they were or ever had been Christians. Having never before had to deal with questions concerning Christians, Pliny applied to the emperor for instructions on three points regarding which he did not see his way clearly: first, whether the age of the accused should be taken into consideration in meting out punishment; secondly, whether Christians who renounced their belief should be pardoned; and thirdly, whether the mere profession of Christianity should be regarded as a crime, and punishable as such, independent of the fact of the innocence or guilt of the accused of the crimes ordinarily associated with such profession. To these inquiries Trajan replied in a rescript which was destined to have the force of law throughout the second century in relation to Christianity. After approving what his representative had already done, the emperor directed that in future the rule to be observed in dealing with Christians should be the following: no steps were to be taken by magistrates to ascertain who were or who were not Christians, but at the same time, if any person was denounced, and admitted that he was a Christian, he was to be punished — evidently with death. Anonymous denunciations were not to be acted upon, and on the other hand, those who repented of being Christians and offered sacrifice to the gods, were to be pardoned. Thus, from the year 112, the date of this document, perhaps even from the reign of Nero, a Christian was ipso facto an outlaw. That the followers of Christ were known to the highest authorities of the State to be innocent of the numerous crimes and misdemeanors attributed to them by popular calumny, is evident from Pliny’s testimony to this effect, as well as from Trajan’s order: conquirendi non sunt. And that the emperor did not regard Christians as a menace to the State is apparent from the general tenor of his instructions. Their only crime was that they were Christians, adherents of an illegal religion. Under this regime of proscription the Church existed from the year 112 to the reign of Septimius Severus (193-211). The position of the faithful was always one of grave danger, being as they were at the mercy of every malicious person who might, without a moment’s warning, cite them before the nearest tribunal. It is true indeed, that the delator was an unpopular person in the Roman Empire, and, besides, in accusing a Christian he ran the risk of incurring severe punishment if unable to make good his charge against his intended victim. In spite of the danger, however, instances are known, in the persecution era, of Christian victims of delation. |

ARTICLE 7

THE REASONS BEHIND THE PERSECUTION OF EARLY CHRISTIANS

Part 2 of 2

THE REASONS BEHIND THE PERSECUTION OF EARLY CHRISTIANS

Part 2 of 2

|

|

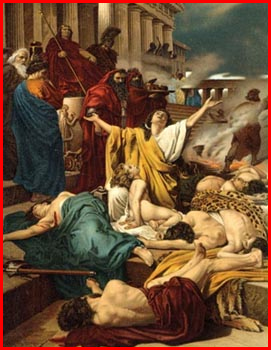

The prescriptions of Trajan on the subject of Christianity were modified by Septimius Severus by the addition of a clause forbidding any person to become a Christian. The existing law of Trajan against Christians in general was not, indeed, repealed by Severus, though for the moment it was evidently the intention of the emperor that it should remain a dead letter. The object aimed at by the new enactment was, not to disturb those already Christians, but to check the growth of the Church by preventing conversions. Some illustrious convert martyrs, the most famous being Sts. Perpetua and Felicitas, were added to the roll of champions of religious freedom by this prohibition, but it effected nothing of consequence in regard to its primary purpose.

The persecution came to an end in the second year of the reign of Caracalla (211-217). From this date to the reign of Decius (250-253) the Christians enjoyed comparative peace with the exception of the short period when Maximinus the Thracian (235-238) occupied the throne. The elevation of Decius to the purple began a new era in the relations between Christianity and the Roman State. This emperor, though a native of Illyria, was nevertheless profoundly imbued with the spirit of Roman conservatism. He ascended the throne with the firm intention of restoring the prestige which the empire was fast losing, and he seems to have been convinced that the chief difficulty in the way of effecting his purpose was the existence of Christianity. The consequence was that in the year 250 he issued an edict, the tenor of which is known only from the documents relating to its enforcement, prescribing that all Christians of the empire should on a certain day offer sacrifice to the gods. This new law was quite a different matter from the existing legislation against Christianity. Proscribed though they were legally, Christians had hitherto enjoyed comparative security under a regime which clearly laid down the principle that they were not to be sought after officially by the civil authorities. The edict of Decius was exactly the opposite of this: the magistrates were now constituted religious inquisitors, whose duty it was to punish Christians who refused to apostatize. The emperor’s aim, in a word, was to annihilate Christianity by compelling every Christian in the empire to renounce his Faith. The first effect of the new legislation seemed favorable to the wishes of its author. During the long interval of peace since the reign of Septimius Severus — nearly forty years — a considerable amount of laxity had crept into the Church’s discipline, one consequence of which was, that on the publication of the edict of persecution, multitudes of Christians besieged the magistrates everywhere in their eagerness to comply with its demands. Many other nominal Christians procured by bribery certificates stating that they had complied with the law, while still others apostatized under torture. Yet after this first throng of weaklings had put themselves outside the pale of Christianity there still remained, in every part of the empire, numerous Christians worthy of their religion, who endured all manner of torture, and death itself, for their convictions. The persecution lasted about eighteen months, and wrought incalculable harm. Before the Church had time to repair the damage thus caused, a new conflict with the State was inaugurated by an edict of Valerian published in 257. This enactment was directed against the clergy — bishops, priests, and deacons — who were directed under pain of exile to offer sacrifice. Christians were also forbidden, under pain of death, to resort to their cemeteries. The results of this first edict were of so little moment that the following year, 258, a new edict appeared requiring the clergy to offer sacrifice under penalty of death. Christian senators, knights, and even the ladies of their families, were also affected by an order to offer sacrifice under penalty of confiscation of their goods and reduction to plebeian rank. And in the event of these severe measures proving ineffective the law prescribed further punishment: execution for the men, for the women exile. Christian slaves and freedmen of the emperor’s household also were punished by confiscation of their possessions and reduction to the lowest ranks of slavery. Among the martyrs of this persecution were Pope Sixtus II and St. Cyprian of Carthage. Of its further effects little is known, for want of documents, but it seems safe to surmise that, besides adding many new martyrs to the Church’s roll, it must have caused enormous suffering to the Christian nobility. The persecution came to an end with the capture (260 AD) of Valerian by the Persians; his successor, Gallienus (260-68), revoked the edict and restored to the bishops the cemeteries and meeting places. From this date to the last persecution inaugurated by Diocletian (284-305) the Church, save for a short period in the reign of Aurelian (270-75), remained in the same legal situation as in the second century. The first edict of Diocletian was promulgated at Nicomedia in the year 303, and was of the following tenor: Christian assemblies were forbidden; churches and sacred books were ordered to be destroyed, and all Christians were commanded to abjure their religion forthwith. The penalties for failure to comply with these demands were degradation and civil death for the higher classes, reduction to slavery for freemen of the humbler sort, and for slaves incapacity to receive the gift of freedom. Later in the same year a new edict ordered the imprisonment of ecclesiastics of all grades, from bishops to exorcists. A third edict imposed the death-penalty for refusal to abjure, and granted freedom to those who would offer sacrifice; while a fourth enactment, published in 304, commanded everybody without exception to offer sacrifice publicly. This was the last and most determined effort of the Roman State to destroy Christianity. It gave to the Church countless martyrs, and ended in her triumph in the reign of Constantine. |

ARTICLE 8

THE NUMBER OF MARTYRS

THE NUMBER OF MARTYRS

|

|

Of the 249 years from the first persecution under Nero (64) to the year 313, when Constantine established lasting peace, it is calculated that the Christians suffered persecution about 129 years and enjoyed a certain degree of toleration about 120 years. Yet it must be borne in mind that even in the years of comparative tranquility Christians were at all times at the mercy of every person ill-disposed towards them or their religion in the empire. Whether or not delation (the exposing and denouncing) of Christians occurred frequently during the era of persecution is not known, but taking into consideration the irrational hatred of the pagan population for Christians, it may safely be surmised that not a few Christians suffered martyrdom through betrayal.

An example of the kind related by St. Justin Martyr shows how swift and terrible were the consequences of delation. A woman who had been converted to Christianity was accused by her husband before a magistrate of being a Christian. Through influence the accused was granted the favor of a brief respite to settle her worldly affairs, after which she was to appear in court and put forward her defense. Meanwhile her angry husband caused the arrest of the catechist, Ptolomæus by name, who had instructed the convert. Ptolomæus, when questioned, acknowledged that he was a Christian and was condemned to death. In the court, at the time this sentence was pronounced, were two persons who protested against the iniquity of inflicting capital punishment for the mere fact of professing Christianity. The magistrate in reply asked if they also were Christians, and on their answering in the affirmative both were ordered to be executed. As the same fate awaited the wife of the delator also, unless she recanted, we have here an example of three, possibly four, persons suffering capital punishment on the accusation of a man actuated by malice, solely for the reason that his wife had given up the evil life she had previously led in his society (St. Justin Martyr, II, Apol., ii). As to the actual number of persons who died as martyrs during these two centuries and a half, we have no definite information. Tacitus is authority for the statement that an immense multitude (ingens multitudo) were put to death by Nero. The Apocalypse of St. John speaks of “the souls of them that were slain for the word of God” in the reign of Domitian, and Dion Cassius informs us that “many” of the Christian nobility suffered death for their Faith during the persecution for which this emperor is responsible. Origen indeed, writing about the year 249, before the edict of Decius, states that the number of those put to death for the Christian religion was not very great, but he probably means that the number of martyrs up to this time was small when compared with the entire number of Christians (cf. Allard, “Ten Lectures on the Martyrs”, 128). St. Justin Martyr, who owed his conversion largely to the heroic example of Christians suffering for their Faith, incidentally gives a glimpse of the danger of professing Christianity in the middle of the second century, in the reign of so good an emperor as Antoninus Pius (138-61). In his “Dialogue with Trypho” (cx), the apologist, after alluding to the fortitude of his brethren in religion, adds, “for it is plain that, though beheaded, and crucified, and thrown to wild beasts, and chains, and fire, and all other kinds of torture, we do not give up our confession; but, the more such things happen, the more do others in larger numbers become faithful. . . . Every Christian has been driven out not only from his own property, but even from the whole world; for you permit no Christian to live.” Tertullian also, writing towards the end of the second century, frequently alludes to the terrible conditions under which Christians existed (“Ad martyres”, “Apologia”, “Ad Nationes”, etc.): death and torture were ever present possibilities. But the new régime of special edicts, which began in 250 with the edict of Decius, was still more fatal to Christians. The persecutions of Decius and Valerian were not, indeed, of long duration, but while they lasted, and in spite of the large number of those who fell away, there are clear indications that they produced numerous martyrs. Dionysius of Alexandria, for instance, in a letter to the Bishop of Antioch tells of a violent persecution that took place in the Egyptian capital, through popular violence, before the edict of Decius was even published. The Bishop of Alexandria gives several examples of what Christians endured at the hands of the pagan rabble and then adds that “many others, in cities and villages, were torn asunder by the heathen” (Eusebius, Church History VI.41 sq.). Besides those who perished by actual violence, also, a “multitude wandered in the deserts and mountains, and perished of hunger and thirst, of cold and sickness and robbers and wild beasts” (Eusebius, l. c.). In another letter, speaking of the persecution under Valerian, Dionysius states that “men and women, young and old, maidens and matrons, soldiers and civilians, of every age and race, some by scourging and fire, others by the sword, have conquered in the strife and won their crowns” (Id., op. cit., VII, xi). At Cirta, in North Africa, in the same persecution, after the execution of Christians had continued for several days, it was resolved to expedite matters. To this end the rest of those condemned were brought to the bank of a river and made to kneel in rows. When all was ready the executioner passed along the ranks and dispatched all without further loss of time (Ruinart, p. 231). But the last persecution was even more severe than any of the previous attempts to extirpate Christianity. In Nicomedia “a great multitude” were put to death with their bishop, Anthimus; of these some perished by the sword, some by fire, while others were drowned. In Egypt “thousands of men, women and children, despising the present life ... endured various deaths” (Eusebius, Church History VII.4 sqq.), and the same happened in many other places throughout the East. In the West the persecution came to an end at an earlier date than in the East, but, while it lasted, numbers of martyrs, especially at Rome, were added to the calendar (cf. Allard, op. cit., 138 sq.). But besides those who actually shed their blood in the first three centuries account must be taken of the numerous confessors of the Faith who, in prison, in exile, or in penal servitude suffered a daily martyrdom more difficult to endure than death itself. Thus, while anything like a numerical estimate of the number of martyrs is impossible, yet the meager evidence on the subject that exists clearly enough establishes the fact that countless men, women and even children, in that glorious, though terrible, first age of Christianity, cheerfully sacrificed their goods, their liberties, or their lives, rather than renounce the Faith they prized above all. |

ARTICLE 9

THE TRIAL OF THE MARTYRS

THE TRIAL OF THE MARTYRS

|

|

The first act in the tragedy of the martyrs was their arrest by an officer of the law. In some instances the privilege of custodia libera, granted to St. Paul during his first imprisonment, was allowed before the accused were brought to trial; St. Cyprian, for example, was detained in the house of the officer who arrested him, and treated with consideration until the time set for his examination.

But such procedure was the exception to the rule; the accused Christians were generally cast into the public prisons, where often, for weeks or months at a time, they suffered the greatest hardships. Glimpses of the sufferings they endured in prison are in rare instances supplied by the Acts of the Martyrs. St. Perpetua, for instance, was horrified by the awful darkness, the intense heat caused by overcrowding in the climate of Roman Africa, and the brutality of the soldiers (Passio SS. Perpet., et Felic., i). Other confessors allude to the various miseries of prison life as beyond their powers of description (Passio SS. Montani, Lucii, iv). Deprived of food, save enough to keep them alive, of water, of light and air; weighted down with irons, or placed in stocks with their legs drawn as far apart as was possible without causing a rupture; exposed to all manner of infection from heat, overcrowding, and the absence of anything like proper sanitary conditions — these were some of the afflictions that preceded actual martyrdom. Many naturally, died in prison under such conditions, while others, unfortunately, unable to endure the strain, adopted the easy means of escape left open to them, namely, complied with the condition demanded by the State of offering sacrifice. Those whose strength, physical and moral, was capable of enduring to the end were, in addition, frequently interrogated in court by the magistrates, who endeavored by persuasion or torture to induce them to recant. These tortures comprised every means that human ingenuity in antiquity had devised to break down even the most courageous; the obstinate were scourged with whips, with straps, or with ropes; or again they were stretched on the rack and their bodies torn apart with iron rakes. Another awful punishment consisted in suspending the victim, sometimes for a whole day at a time, by one hand; while modest women in addition were exposed naked to the gaze of those in court. Almost worse than all this was the penal servitude to which bishops, priests, deacons, laymen and women, and even children, were condemned in some of the more violent persecutions; these refined personages of both sexes, victims of merciless laws were doomed to pass the remainder of their days in the darkness of the mines, where they dragged out a wretched existence, half naked, hungry, and with no bed apart from the damp ground. Those were far more fortunate who were condemned to even the most disgraceful death, in the arena, or by crucifixion. |

Web Hosting by Just Host