| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

The Greatest and Most Important Week in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

THE DAYS LEADING UP TO PALM SUNDAY

VENERABLE MARY OF AGREDA

The Mystical City of God

The Mystical City of God

|

Our Savior continued to perform His miracles in Judea. Among them was also the resurrection of Lazarus in Bethany, whither He had been called by the two sisters, Martha and Mary. As this miracle took place so near to Jerusalem, the report of it was soon spread throughout the city.

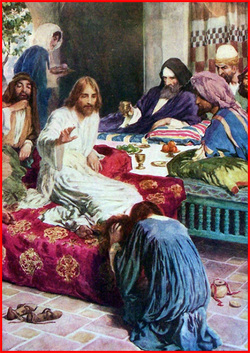

The Priests and Pharisees, being irritated by this miracle, held a council (John 9:17), in which they resolved upon the death of the Redeemer and commanded all those that had any knowledge of His whereabouts, to make it known; for after the resurrection of Lazarus, Jesus retired to the town of Ephraim, until the proximate feast of the Pasch should arrive. As the time of celebrating it by His own Death drew nigh, He showed Himself more openly with His twelve disciples, the Apostles; and He told them privately that they should now get themselves ready to go to Jerusalem, where the Son of man, He Himself, should be delivered over to the chiefs of the Pharisees, bound as a prisoner, scourged, and ill-treated unto the death of the Cross (Matthew 20:18). In the meanwhile the priests kept a sharp watch to find Him among those who came to celebrate the Pasch. Six days previous He again visited Bethania, where He had called Lazarus to life, and where He was entertained by the two sisters. They arranged a banquet for the Lord and His Mother, and for all of his company. Among those that were at table with them, was also Lazarus, whom He had brought back to life a few days before. While our Savior, according to the custom of the Jews, was reclining at this banquet, Magdalen, filled with divine enlightening and most magnanimous sentiments, entered the banquet hall. As an outward token of her ardent love toward Christ, her divine Master, she anointed His feet and poured out over them and over His head an alabaster vase filled with a most fragrant and precious liquor, composed of spikenard and other aromatic ingredients. Then she wiped His feet with her hair, just as she had done at another occasion in the house of the Pharisee, related by St. Luke (Luke 7:38). Although the other three Evangelists in relating this second anointing, apparently differ as to some of the circumstances; yet I was not informed that they refer to different anointing or speak of more than one woman, but that they refer only to Magdalen, who was moved to these acts of devotion by inspiration of the Holy Ghost and by her own burning love toward Christ the Redeemer. The fragrance of this ointment filled the whole house, for she had procured a large quantity, and of the most precious kind; nor did she stint it in any way, but broke the vessel in token of her generous love and devotion to the Master. The avaricious Apostle Judas, who wished to get possession of the ointment, in order to sell it for the increase of his purse, began to criticize this mysterious anointing of his Master and also to stir up some of the other Apostles, under pretext of poverty and of charity toward the poor (John 12:5). These, he said, are defrauded of their alms by this lavish expense and waste of so costly an article. At the same time all this had been ordained by Divine Providence, while Judas acted only as an avaricious and disgruntled hypocrite. The Teacher of truth and life defended Magdalen against this accusation of inconsiderate prodigality. He commanded Judas and the others not to harass her (Matthew 24:10), since her action had not been vain or without good cause. He told them the poor would not on that account lose the alms, which they should receive each day, whereas such opportunity of showing honor to His Person would not be |

afforded every day; that the anointing had been performed by this generous and loving woman through enlightenment of the holy Spirit and as a prophetic announcement of the mysterious unction the Savior was so soon to undergo in the torments of his Death and at his burial.

Nothing of all this the perfidious disciple took to heart, but on the contrary he conceived a furious wrath against his Master on account of His thus justifying the action of Magdalen. Lucifer, profiting by the disposition of this depraved heart, incited it to new upwellings of avarice, anger, and mortal hate against the Author of life. Thenceforth Judas schemed to bring about His Death, and resolved, as soon as he should come to Jerusalem, to betray Him to the Pharisees and help to discredit Him in their eyes, as he afterwards did. After this banquet he betook himself secretly to Jerusalem and told them that his Master taught new laws contrary to those of Moses and of the emperors; that He was addicted to banqueting, a friend of depraved and profane company; that He had admitted, as His followers, many of a wicked life, both men and women; that without delay they should see such conduct stopped lest ruin overtake them when it was too late to secure relief. As the Pharisees were already of the same mind and were instigated by the same prince of darkness, they gladly accepted his advice. With them therefore he agreed on a price for the betrayal of Christ our Savior. All the thoughts of Judas lay open not only to his divine Master, but also to his most Blessed Mother. The Lord said nothing to Judas in regard to this matter, but continued to deal with him as a kind Father and to enlighten his obstinate heart. His Mother, however, redoubled her admonitions and gentle endeavors to withdraw Judas from the precipice; and, on this night of the banquet, which was that preceding Palm Sunday, she called him aside to speak to him alone, representing to him amid a flood of tears and with most sweet and persuasive words, what terrible danger threatened him if he should persist in his intentions. She asked him to give up his designs and, if he was offended at his Master, to take vengeance on her. For this was a smaller evil, since she was only a creature, while He was his Master and the true God. In order to satisfy the avarice of this insatiable heart, she offered him some presents, which she had received for this purpose from Magdalen. But none of her efforts were of any avail with this hardened soul, nor did any of these sweet and living words soften this more than adamantine heart. On the contrary, as he did not find an answer and the exhortations of the most prudent Queen were so urgent, he lashed himself into greater fury, showing his wrath by a sullen silence. He was, however, not ashamed to take what she offered to him; for his avarice was equal to his perfidy. The most Blessed Mary then left him and betook herself to her Son and Master. Full of the bitterest sorrow, she cast herself weeping at his feet. In her exquisite grief and compassion, she wished to bring some consolation to the sacred humanity of Christ her Son, whom she now beheld suffering of the sorrow unto death, which He afterwards manifested in the presence of His disciples (Matthew 24:38). Of this kind were the sufferings of Christ for the sins of those men who were to misapply his Passion and Death. HERE ENDS THE EXTRACT FROM THE MYSTICAL CITY OF GOD |

|

THE RESURRECTION OF LAZARUS

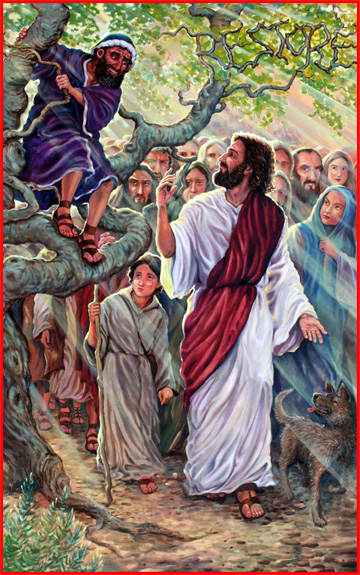

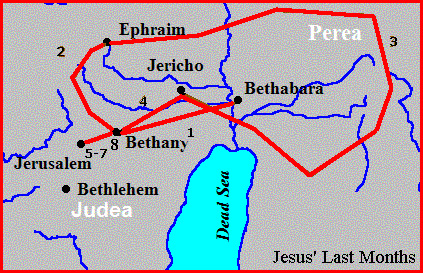

The Apostles no longer had any doubt that he was to be slain. There were not only his own words, but the intentions of the leaders of Israel were quite clear. They knew that he was safe enough in Herod's country. They could only hope that nothing would take him back to Judea. But something did take him back. Lazarus. "whom He loved", lay ill unto death in Bethany; Martha and Mary had sent our Lord a message. There were two towns called Bethany. The Bethany of Martha, Mary and Lazarus was in Judea, less than two miles from Jerusalem, on the lower slope of the Mount of Olives. Even if Jesus had slipped into the town quietly, and left it quietly, he would have been taking an immense risk. He went in openly, and worked the most spectacular miracle of his life. After getting the message from Martha and Mary, Jesus let two days go by. Then He said to the Twelve: "Let us go into Judea again" (John 11:7). They reminded him how recently the men of Judea had sought to stone Him. When He told them that Lazarus had died, they must have felt that there was now no point in His going to Bethany after all. Their relief did not last long. He was still bent upon going. From where Jesus was now staying, to go into Judea meant to go to Jerusalem or its vicinity and hence right into the lair of his enemies. The disciples thought immediately of the danger and reminded him of it: "Rabbi, just now the Jews were seeking to stone thee; and dust thou go there again?" Jesus said: "Lazarus, our friend, sleeps. But I go that I may wake him from sleep." These words seemed to confirm the disciples' mistaken interpretation of Jesus' answer to the sisters' message ("this sickness is not unto death") and also of Jesus' two-day delay, and so they answered confidently: "Lord, if he sleeps, he will be safe." Medicine at that time, in fact, considered deep sleep a sign that the body was reacting against the sickness and beginning to cast it off. Here was another reason, then, for not going into Judea to visit Lazarus now, in order not to disturb him. So then Jesus said to them plainly: “Lazarus is dead; and I rejoice on your account that I was not there, that you may believe. But let us go to him." The disciples were thunderstruck by the news of Lazarus' death, nor did they even remotely suspect Jesus' real intentions. Since the worst had befallen and there was nothing more to be done, why should they persist in going into Judea straight into that den of chief priests and Pharisees? The disciples did not relish the idea of the journey at all, and they hesitated between their fear of the Pharisees and their respect for Jesus. On the other hand, the Master seemed fixed in His determination to go. Therefore they had to go with Him even at the cost of not coming back, of losing their lives down there, among the hate-ridden enemies they were about to provoke. At that point, Thomas said one of the great things: "Let us also go, that we may die with Him." When the time came, Thomas ran away with the others. But he meant it when he said it, and there was splendor in it—all the more, perhaps, because he did run away later: courage costs braver men less! This is the first thing we have heard Thomas say. JESUS ARRIVES IN BETHANY AFTER THE DEATH OF LAZARUS Martha came to meet him outside the town, with the words "Lord, if you had been here my brother would not have died. But I also know that whatsoever you ask of God, God will give you." That last phrase can only mean that there was a faint quiver of a hope in her that he might bring her brother back to life. Had she, perhaps, heard of the widow's son resurrected in Naim, or of Jairus' daughter, both raised from the dead in Galilee? But the hope, if it was there at all, could have been no more than the faintest stirring. For when Jesus said, "Your brother shall rise again", she did not take it as the answer to her hopes. She spoke as if He meant only that final resurrection of all men, which the Pharisees taught and the Sadducees denied. There was nothing in His next statement to indicate that he meant to bring her brother back to life in this world. And when, standing by the tomb, He told them to take away the stone, no hope seems to have stirred in her. She could think only of how very dead Lazarus must be by now: "Lord, by this time he stinks, for he is now four days dead." After all, Jairus' daughter and the Nain boy were barely dead, they had not yet been buried! His answer was simply: "Did I not say to you, that if you believe, you shall see the glory of God?" Few miracles are led up to in such detail. But the miracle itself is told swiftly. Our Lord cried with a loud voice,"Lazarus, come here!"—as it were, "Come to me!" Lazarus emerged, still wrapped for his burial, and our Lord said,"Loose him and let him go." Let us remind ourselves that this miracle was worked, quite explicitly, for the effects it would produce upon friend and enemy alike. It is the only time, to take one example, that Jesus actually says He is speaking aloud to His Father"because of the people who are standing near"— He wants them to hear. And many did indeed believe because of what they had heard and seen. But it seems beyond doubt also that the effect upon his enemies was part of the purpose of the miracle. It made His death certain. The Pharisees had wanted Him slain these many months. But, with this miracle, the Sadducees (the priests) are brought to will His death for the first time. And it was they, with the high priesthood in their grip, who had the right—and the influence with the Romans—to bring it about. CAIPHAS ENTERS THE SCENE In all His parables, there is only one character to whom Jesus gives a name—Lazarus, which means "God has helped". He, we remember, "died and was carried by the angels into Abraham's bosom"— a phrase for the place where the just of Israel waited till Christ's redeeming sacrifice should open heaven to men. We remember, too, how the rich man, "buried in Hell", asked Abraham to send Lazarus the beggar to warn his five brothers still on earth of what might await them. Abraham dismissed the request—they would not believe even if Lazarus came back from the dead. That was the parable. And now, in fact not parable, a man named Lazarus did come back from the dead, called by Jesus of Nazareth. And they did not believe. Instead the leaders of the Jews decided to kill Jesus. They planned to kill Lazarus too (John 12:10)— return Him to Abraham's bosom, so to speak, from which He had been thus irregularly dragged. We must try to follow the thought processes of the Jewish leaders. The Pharisees, we know, had long determined that Jesus must die for the crime of contradicting the traditions which were the whole of religion to them. But the Sadducees had no special attachment to the traditions. These men were essentially power politicians, they had secured for themselves the high priesthood and the total control of the Temple, they knew how to handle their Roman overlords. They would not have bothered about Jesus’ religious heresies— they thought the Pharisees heretical anyhow. But upsetting the Romans was a very different matter. The masters of the world were always on the watch for men who might lead subject peoples to rise in revolt. With the raising of a man from the dead on Jerusalem's very doorstep, the Sadducees suddenly saw Jesus as dangerous. It looked as if He was ready to make His bid for power. Even if He had no such intention, this was the sort of miracle that would have the Rome-hating crowds thronging after Him. If that happened, or even if it was seen as a possibility, Rome might destroy the holy place, the Temple, and eliminate the Jews of Palestine as the national unit they had managed to remain. Now we meet Caiphas for the first time. He was high priest, son-in-law of Annas, the high priest Rome had deposed fifteen years earlier. With Sadducees and Pharisees gathered in council (Sanhedrin) to think out what had best be done to save the Temple and the nation, Caiphas touched off the discussion: "You know nothing. Surely you realize that it is best for us that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation should not perish" (John 11:49-50). He only meant that, if one man was a threat to national survival, then the obvious thing was to kill him. But the Evangelist tells us that, unknown to himself, the high priest was prophesying that Jesus should die for the Jews, not only for the Israel of blood and race, but for the Israel of God—all men who should be united with God in Christ. It would have startled Caiphas beyond words to know that that was what he was actually saying. To have the Sadducees determined upon his death changed the situation considerably. They held the high offices in Judea, they were in daily contact with the Romans. They could get the Romans not only to consent to his death, though that was necessary, but actually to put him to death, thus saving themselves from the kind of odium that had clung to Herod of Galilee ever since the beheading of the Baptist. Romans could take odium in their stride, especially if they felt they were acting with strict legality. ESCAPE TO EPHRAIM THEN BACK TO BETHANY VIA JERICHO Following the decision, uttered by Caiaphas and accepted by Sadducees and Pharisees, that he must die, Jesus, for safety’s sake, went to Ephraim — probably, though not certainly, a place fifteen miles from Jerusalem, on the edge of desert. The Passover was near, says St. John (11:55), and He would be in Jerusalem at the Passover for His death. But how near was it? And what road did He take back? From the Gospels, we cannot be certain of the answer to either question. In any case, He did not stay at Ephraim many days. The first companies of pilgrims were beginning to travel up toward the Holy City for the Pasch, where His arrival, too, was awaited from moment to moment. In any case, to make sure the council's deliberation would not be confined to wishful thinking, "the chief priests and Pharisees had given orders that, if anyone knew where He was, he should report it, so that they might seize Him" (John 11:57). Despite these orders, Jesus left his retreat at Ephraim at the beginning of the month Nisan and set out for Jerusalem along the road that followed the Jordan and passed by way of Jericho. The disciples sensed tragedy in the air, and they walked slowly and reluctantly, though ahead of them strode the Master, betraying no reluctance whatever: "They were now on their way, going up to Jerusalem; and Jesus was walking on in front of them, and they were in dismay, and those who followed were afraid" (Mark 10:32). What we know for certain is that He did go through Jericho and Bethany on His way to Jerusalem, and a glance at the map suggests that He went to Jericho straight from Ephraim. On the first stage of the return journey Saint Mark tells us that Jesus walked ahead of the Twelve and that they were afraid. At last He was walking toward His death, and they felt Him different. There were two groups in their caravan, then; the first was composed of the Apostles and a few of Jesus' oldest and most devoted disciples, and He Himself walked on alone ahead of them so that they were "dismayed"; the second, which "followed" at a certain distance, was made up of other more recent disciples, together with Paschal pilgrims, perhaps, who already knew Jesus and were concerned for Him, and all these especially "were afraid." To the right of them the hills of Jerusalem brooded in the distance. It may be that He went north into Samaria, to the border of Galilee, before moving over to Jordan, and then south by way of Jericho and Bethany. If He did, then the healing of the ten lepers, with the Samaritan coming back to thank Him, may have taken place at this time (Luke 17:12). This episode has one point of uniqueness: it is the only occasion on which Our Lord mentions thanksgiving as a duty (a duty which only the Samaritan rendered). Otherwise He is silent about it—strangely, we may feel. Even in the Our Father, the prayer He Himself gave us as a model, there is no clause in which God is thanked. 1. Bethabara to Bethany and the raising of Lazarus from the dead. (John 11:1-46)

2. From Bethany to Ephraim. (John 11:54) 3. From Ephraim through Perea. (Mark 10:1). A woman was healed of her longtime infirmity. (Luke 13:11-13). Jesus blesses the little children. (Luke 18:15-17) 4. From Perea through Jericho to Bethany. Blind Bartimeus healed in Jericho. (Mark 10:46-52). Jesus in Bethany 6 days before passover (John 12:1) 5. Bethany to Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. 6. Jesus returns to preach in Jerusalem on Monday and Tuesday. Jesus Upset. Second cleansing of the temple (Matthew 21:12-13). Woes to scribes and Pharisees (Matthew 23). 7. Vision of last days (Matthew 24, Mark 13, Luke 21). 8. Jesus stays in Bethany on Wednesay until going to Jerusalem on Thursday for the Passover. (Mark 14:1-9). Compare Matthew 26:1-13, Mark 14:3-9, Luke 7:36-50, John 12:1-11 DETAILED PREDICTION OF THE PASSION Then he gave them ground for their fear, with the fullest, most detailed prediction yet of His Passion and Death and Resurrection. Here is how Mark (10:33) records Peter's memory of what He said: "We go up to Jerusalem and the Son of Man shall be betrayed to the chief priests, and to the scribes and ancients, and they shall condemn Him to death and shall deliver Him to the Gentiles. And these shall mock Him, and spit on Him, and scourge Him, and kill Him. And the third day He shall rise again." Considering the extreme clarity of this statement; considering the two earlier, quite clear, though not quite so detailed, foretellings of the Death and Resurrection that awaited Him (Matthew 16:21 and 17:21); considering that the leaders of the Jews had made their own intentions clear; considering that Thomas had expressed the mind of all of them, when he said that, if their Lord returned to Judea, it would mean His death and the Twelve must be prepared to die with Him—we may find St. Luke's comment here rather puzzling: "They understood none of these things, and this word was hid from them" (18:34). Soon after, Matthew and Mark have Christ saying, "The Son of Man is come not to be served but to serve, and to give His life a redemption for many" — Daniel's “Son of Man” and Isaias’ “Suffering Servant” are one and the same person. JAMES AND JOHN WANT THE HIGHEST PLACES Whatever sense the Twelve made of what they had just heard, two of them still counted on a happy ending. James and John, either on their own account (Mark ch. 10) or letting their mother speak for them (Matthew ch. 20), made a claim to preferment in the Kingdom—that they might sit one on Christ's right, the other on His left. One thing they had not grasped, namely the nature of the Kingdom; one thing they had forgotten, namely that Peter had been promised primacy in the Kingdom. Jesus' answer makes no reference to Peter, but contains its own kind of reminder of what the Kingdom was to be: "You do not know what you are asking. Can you drink of the chalice that I drink of, or be baptized with the baptism wherewith I am baptized?" What He meant may very well have been the humiliation and the agony of which He had just been speaking to them. Whatever they thought He meant, the brothers answered in all confidence, "We can!" To which Our Lord answered, "You shall indeed!" --James would remember those words at his beheading by Agrippa, and John in his exile at Patmos: but, Jesus continued, the places of honor in the Kingdom, here upon earth or in the glory of Heaven, were not for Him to dispose of, but His Father. We get the impression that the request had been made, sensibly we feel, at a moment when the other ten were not there. But they came to hear of it and "began to be much displeased at James and John" (Mark 10:41). FATEFUL JOURNEY TOWARDS DEATH The journey from Ephraim was the last Jesus would make to Jerusalem, and Jericho and Bethany were its last stages. The Twelve felt in their bones that it was to be decisive (but what would the decision be?). The crowds knew it too—they must have been warned by the command issued by the chief priest and the Pharisees that anyone who knew where Jesus was should inform them, that they might arrest him (John 11:56). Jesus knew He was walking to His death. The crowds knew it, which made them more anxious for a last look. Only the Apostles (not Thomas, one imagines) clung to their own hope—with James and John, backed by their mother, applying for places on His right hand and His left: John and his mother would be on Calvary and would see who occupied those two places! Miracles on the Road: Blind Men in Jericho They came to Jericho, twenty miles from Jerusalem. It was very much Herod the Great's city, he had largely built it and had died in it; his appalling son Archelaus had built himself a palace there. Near the city Jesus healed two blind men—Mark and Luke concentrate on one of them, the Amore trustful, as we may suppose; Matthew tells us of the other. They remind us of two other blind men whose sight Jesus had restored (Matthew 9:27), particularly in their persistence, and in their hailing Him as Son of David. That title mattered more here in Jericho, with the Kingdom a vivid possibility in everybody's mind. The Twelve, and neighbors in the crowd, told them to stop their shouting. But Jesus called them, questioned them, healed them. They joined the group that straggled after Him. Miracles on the Road: Conversion of Zacchaeus Inside Jericho He once again converted a publican, Zacchaeus, the word means "pure", which tax payers may have thought a name ill-suited to the chief tax collector of the region. He was a little man, too small to see Jesus over the heads of the crowd. So he climbed a tree. It is hard to imagine any prominent official doing anything so undignified today: it was just as improbable then. The people near the tree must have been as much interested in the tax collector up it as in Jesus coming their way. Arrived at the tree, Jesus addressed Zacchaeus by name—he must have heard a dozen people saying the name at once—and said, "Make haste and come down; I am to lodge today at your house." So the tax collector dropped from the tree and was host to Jesus. A bad apple drops from the tree and becomes a good apple! Zacchaeus became a new man. "Here and now, Lord," he said, "I give half of what I have to the poor; and if I have wronged anyone in any way, I make restitution of it fourfold"— this last must have made a considerable inroad on the half of his fortune he was keeping for himself! Before long, Our Lord and His group were on their way to Bethany. BETHANY BANQUET From Jericho Jesus went to Bethany. He was now within two miles of Jerusalem and a week of Calvary. It is probable that, out of respect for the Sabbath rest, Our Lord did not undertake the journey from Jerusalem to Bethany on Saturday, but traveled on Friday afternoon, reaching His destination before sunset. In Bethany we find Him still with Lazarus and Martha and Mary. But this time the great scene is not in their house, but in the house of one Simon called "the leper". Why are we told this about him? Possibly because Jesus had healed him. The inhabitants of Bethany, remembering the great miracle of the raising of Lazarus, wished to honor Jesus with a banquet, or rather a supper, given on Saturday after sundown, i.e., when, according to Jewish reaming, the Sabbath was over and the next day had begun. Public Banquet at the house of Simon the Pharisee The supper was not a private affair, arranged and attended only by the beloved family at Bethany, who surely would have preferred to have had our Lord dine with them alone in the intimacy of their home. It was, instead, a kind of public function, organized in the name of the whole town. Consequently it was held in the house of an important personage, a leading citizen named Simon the leper. Perhaps Simon had been cured of his disease by Jesus, and was now showing his gratitude by holding the public celebration at his house. Doubtless Lazarus was present at the banquet, and was stared at by everyone; in fact, St. John (12:9) says that many Jews came to Bethany, "not only because of Jesus, but that they might see Lazarus, whom he had raised from the dead." Mary Comes to Anoint Jesus On the evening of the last Sabbath before Calvary, Simon gave a banquet for our Lord, with Lazarus one of the guests, and Martha waiting at table. Once more Mary leaves Martha to get on with the serving and herself chooses the better part: she anoints Jesus' head and His feet with precious ointment, and wipes His feet with her hair, so that "the house was filled with the odor of the ointment." Simon the Pharisee and Judas Iscariot Criticize Mary There are three accounts of the scene, given by Mark (14:3-6), Matthew (26:6-13), and John (12:1-11). Read especially John's. He alone tells us that Lazarus was a guest, that it was Mary who did the anointing, that she anointed Jesus' feet, as well as His head. All speak of the indignation her act caused, but John alone tells us that Judas Iscariot uttered it and was rebuked by Jesus. It looks as if this was for Judas the last straw: a few days later he agreed to sell his Master for thirty pieces of silver. Observe the reason Judas gives—"Why was not this ointment sold for three hundred pence, and given to the poor?"—three hundred pence would have supported a workman for a year. Observe John's comment: "He said this, not because he cared for the poor; but because he was a thief, and carried the purse"—he was treasurer for the Twelve, and had been dipping into the small treasury. There is no point in thinking up nobler reasons, as some have done, for Judas' handing over of Jesus to His slayers—as, for instance, that his sole desire was to force Him to show His power and take over His Kingdom at once. John knew him. John said he was a thief. One and the Same Mary, Perhaps Two Separate Banquets? It will have been noticed that St. Luke, who does describe that earlier meal in Bethany at which Martha served and Mary adored (Luke ch.10), does not mention this one. But then Luke (7:36-50) is the only one to tell of an anointing by a sinful woman, as Jesus sat at table in Capernaum, the host, there too, being named Simon. Was that the same incident? We know that Luke is not concerned with strict chronological order. He might have had reasons of his own for describing the Bethany scene in among a series of happenings in Capernaum. There are similarities, indeed, yet they read like separate incidents. In Capernaum, the host is hostile, or at least not friendly. He shows the bare civilities, none of the courtesies. In Bethany, Lazarus is a fellow guest and Martha helps with the serving—we cannot imagine any courtesy left unshown with Martha there. We note also the difference of the reactions to the extravagant gesture of the anointing. In Capernaum the criticism is of Christ—if He had been a true prophet, He would have known the woman's sinfulness and not allowed her near Him. In Bethany, the criticism is of the woman— the money might have been spent upon relieving the miseries of the poor (true, but Jesus reminded them that they had Himself only briefly, the poor would be there for their charity for the rest of their lives). If there were two anointings, were there two anointers? Was Mary of Bethany the "sinful woman" of the Capernaum scene? And was either (or both?) Mary Magdalen? The Gospels do not answer one question or the other. One can only record an impression that the two anointings were the work of one woman: the similarities are too great for coincidence—especially the utterly improbable drying of His feet with the woman's hair. Even the alabaster vase of Capernaum was surely the one used in Bethany never to be used a third time for, as Mark tells us, Mary broke the neck of it before pouring out the oil of nard. Was Mary of Bethany Mary Magdalen? Glance at Jesus' answer to the criticism of her extravagance: it is given slightly differently by Matthew, Mark, and John: but in all it linked her act with the anointing of His body for burial. And Mary Magdalen was one of those who brought the ointment to the tomb—the ointment they did not need to use. Here in Bethany was the anointing for the burial. Besides, the Roman Church has always held that Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus, was also Mary Magdalen, the one caught in adultery and posssesed by seven devils |

Web Hosting by Just Host