| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

The Greatest and Most Important Week in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

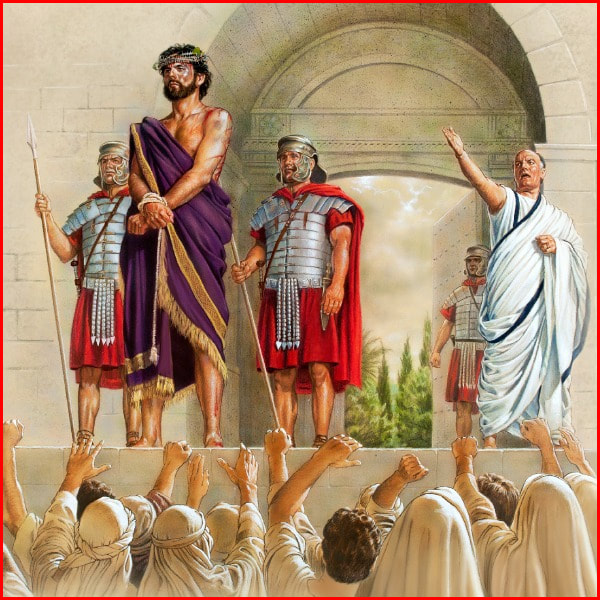

PONTIUS PILATE

|

Pontius Pilate was the Roman prefect (governor) of Judea, a sub-province of Syria, who ordered the crucifixion of Jesus. As prefect, Pilate commanded Roman military units, authorized construction projects, arranged for the collection of imperial taxes, and decided civil and criminal cases. Pilate was effectively a dictator; so long as he kept Rome happy, he had absolute power, including power of life and death.

Pilate could command legionary forces but only small ones, and so in military situations, he would have to yield to his superior, the legate of Syria, who would descend into Palestine with his legions as necessary. As governor of Judaea, Pilate would have small auxiliary forces of locally recruited soldiers stationed regularly in Caesarea and Jerusalem, such as the Antonia Fortress, and temporarily anywhere else that might require a military presence. The total number of soldiers at his disposal would have numbered anywhere from a minimum of 3,000 to a maximum of around 6,000, depending upon what was happening in Jerusalem. For example, when the population of Jerusalem swelled to two or three times the normal number during the festivals—especially the celebration of the Passover, the Pasch, then Pilate would need more troops to keep order. To release Jesus, which is what he preferred to do, would have, most likely, caused a riot—given the powerful influence of the High Priests, Scribes, Pharisees and Sadducees, who were all stacked against Jesus. Pilate could have lost control of the city, and possibly the province. Therefore, Pilate sacrificed Jesus to preserve Roman rule and his own career. During his ten-year tenure as prefect, Pilate had numerous confrontations with his Jewish subjects. According to Jewish historian Josephus, Pilate’s decision to bring into the holy city of Jerusalem, “by night and under cover, effigies of Caesar”, outraged Jews, who considered the images idolatrous. Jews carried their protest to Pilate’s base in Caesaria. Pilate threatened the protesters with death, but when they appeared willing to accept martyrdom he relented and removed the offending images. Again according to the Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, Pilate provoked another outcry, from his Jewish subjects, when he used Temple funds to build an aqueduct. It seems likely that at the time of the trial of Jesus, civil unrest had again broken out in Jerusalem. Pilate’s lack of concern for Jewish sensibilities was accompanied―according to the historian Philo, writing in 41 AD―by corruption and brutality. Philo wrote that Pilate’s tenure was associated with “briberies, insults, robberies, outrages, wanton injustices, constantly repeated executions without trial, and ceaseless and grievous cruelty.” Philo may have overstated the case, but there is little to suggest that Pilate would have any serious reservations about executing a Jewish rabble-rouser, into which group the Priests and Pharisees had categorized Jesus. Although Pilate spent most of his time in the coastal town of Caesaria, he traveled to Jerusalem for important Jewish festivals. While in Jerusalem, he stayed in the praetorium, which--there is a debate about this--was either a former palace of Herod the Great or a fortress located at the northwest corner of the Temple Mount. The Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, reported that Pilate resided at the palace. Christian accounts of the trial of Jesus suggest either that Pilate played no direct role in the decision to execute Jesus (Peter), or that he ordered the crucifixion of Jesus with some reluctance (Mark) or with great reluctance (Luke, John). It is clear that the Roman prefects had a variety of options available for dealing with a potential source of trouble such as Jesus. These options included flogging, sending the matter back to the Sanhedrin, or referring the case to Herod Antipas, ruler of Galilee. Given what is known about Pilate’s concern with crowd control, it is hard to imagine that he would not have willingly acceded to a request, from high Jewish officials, to deal harshly with anyone who proclaimed himself “King of the Jews.” Pilate undoubtedly knew that past messianic claims had led to civil unrest. It seems likely that he would have been eager to end the potential threat to the existing order presented by the ‘subversive’ teaching and claims of Jesus. The form of execution used―crucifixion―establishes that Jesus was condemned as a violator of Roman, not Jewish, law—though the Jews would have killed Jesus by stoning if they did not have their hands ‘tied’ by the Roman authorities. Pilate’s repeated difficulties with his Jewish subjects was the apparent cause of his removal from office, in 36 AD, by Syrian governor Vitellius. Following his removal from office, Pilate was ordered to Rome to face complaints of excessive cruelty. He was exiled in Vienne, France, where he died soon afterwards, somewhere around 39 AD. Pontius Pilate was the Roman prefect (governor) of Judea, a sub-province of Syria, who ordered the crucifixion of Jesus. As prefect, Pilate commanded Roman military units, authorized construction projects, arranged for the collection of imperial taxes, and decided civil and criminal cases. Pilate was effectively a dictator; so long as he kept Rome happy, he had absolute power, including power of life and death. Pilate could command legionary forces but only small ones, and so in military situations, he would have to yield to his superior, the legate of Syria, who would descend into Palestine with his legions as necessary. As governor of Judaea, Pilate would have small auxiliary forces of locally recruited soldiers stationed regularly in Caesarea and Jerusalem, such as the Antonia Fortress, and temporarily anywhere else that might require a military presence. The total number of soldiers at his disposal would have numbered anywhere from a minimum of 3,000 to a maximum of around 6,000, depending upon what was happening in Jerusalem. For example, when the population of Jerusalem swelled to two or three times the normal number during the festivals—especially the celebration of the Passover, the Pasch, then Pilate would need more troops to keep order. To release Jesus, which is what he preferred to do, would have, most likely, caused a riot—given the powerful influence of the High Priests, Scribes, Pharisees and Sadducees, who were all stacked against Jesus. Pilate could have lost control of the city, and possibly the province. Therefore, Pilate sacrificed Jesus to preserve Roman rule and his own career. During his ten-year tenure as prefect, Pilate had numerous confrontations with his Jewish subjects. According to Jewish historian Josephus, Pilate’s decision to bring into the holy city of Jerusalem, “by night and under cover, effigies of Caesar”, outraged Jews, who considered the images idolatrous. Jews carried their protest to Pilate’s base in Caesaria. Pilate threatened the protesters with death, but when they appeared willing to accept martyrdom he relented and removed the offending images. Again according to the Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, Pilate provoked another outcry, from his Jewish subjects, when he used Temple funds to build an aqueduct. It seems likely that at the time of the trial of Jesus, civil unrest had again broken out in Jerusalem. Pilate’s lack of concern for Jewish sensibilities was accompanied―according to the historian Philo, writing in 41 AD―by corruption and brutality. Philo wrote that Pilate’s tenure was associated with “briberies, insults, robberies, outrages, wanton injustices, constantly repeated executions without trial, and ceaseless and grievous cruelty.” Philo may have overstated the case, but there is little to suggest that Pilate would have any serious reservations about executing a Jewish rabble-rouser, into which group the Priests and Pharisees had categorized Jesus. Although Pilate spent most of his time in the coastal town of Caesaria, he traveled to Jerusalem for important Jewish festivals. While in Jerusalem, he stayed in the praetorium, which--there is a debate about this--was either a former palace of Herod the Great or a fortress located at the northwest corner of the Temple Mount. The Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, reported that Pilate resided at the palace. Christian accounts of the trial of Jesus suggest either that Pilate played no direct role in the decision to execute Jesus (Peter), or that he ordered the crucifixion of Jesus with some reluctance (Mark) or with great reluctance (Luke, John). It is clear that the Roman prefects had a variety of options available for dealing with a potential source of trouble such as Jesus. These options included flogging, sending the matter back to the Sanhedrin, or referring the case to Herod Antipas, ruler of Galilee. Given what is known about Pilate’s concern with crowd control, it is hard to imagine that he would not have willingly acceded to a request, from high Jewish officials, to deal harshly with anyone who proclaimed himself “King of the Jews.” Pilate undoubtedly knew that past messianic claims had led to civil unrest. It seems likely that he would have been eager to end the potential threat to the existing order presented by the ‘subversive’ teaching and claims of Jesus. The form of execution used―crucifixion―establishes that Jesus was condemned as a violator of Roman, not Jewish, law—though the Jews would have killed Jesus by stoning if they did not have their hands ‘tied’ by the Roman authorities. Pilate’s repeated difficulties with his Jewish subjects was the apparent cause of his removal from office, in 36 AD, by Syrian governor Vitellius. Following his removal from office, Pilate was ordered to Rome to face complaints of excessive cruelty. He was exiled in Vienne, France, where he died soon afterwards, somewhere around 39 AD. Pontius Pilate: A Lesson on Political Power One wonders if there are really any new things in the world, or if only the same things are happening to different people. Take, for example, the relation of politics and religion. Those who have their finger on the pulse of contemporary civilization have probably noted that there are two contradictory charges against religion today. The first is that religion is not political enough; the other is that religion is too political. On the one hand, the Church is blamed for being too divine, and on the other, for not being divine enough. It is hated because it is too heavenly and hated because it is too earthly. Notice that these were the very two charges for which Christ Himself was condemned: The religious judges, Annas and Caiphas, found Him too religious; the political judges, Pilate and Herod, found Him too political. Caiphas, the religious judge, standing before his judgment seat, asked: “I order you to tell us under oath before the living God whether you are the Messias, the Son of God” (Matthew 26:63). As the question rang out through the marble hall and was succeeded by a silence vibrant with emotion, Christ finally raised His eyes to the judge and answered: “You have said so” (Matthew 26:64). A gleam of satisfaction lighted the judge’s face. At last he had triumphed! But he must not show it, so under the veil of horrified indignation at the insult offered to God’s supreme majesty by declaring Himself to be God, he tore his garments from bottom to top, crying out, “He has blasphemed!” (Matthew 26:65). Christ is too religious! Too heavenly! Too spiritual! Too much interested in souls! Too divine! Because He was too religious, He was not political enough. The religious judges said that He had no concern for the fact that the Romans were their masters, and that they might take away their country (John 11:4748). By talking about a spiritual kingdom, a higher moral law, and His divinity, and by becoming the leader of a spiritual crusade, He was accused of being indifferent to the needs of the people and national well-being. The Romans would not tolerate anyone with such an appeal. He would bring down retribution from Rome. Their armies would come and destroy them. After all, what good is religion, anyway, if it has no part in the political, economic, and social setup of a country. So Caiphas decided—Better let the one man die rather than the whole nation should perish. Within a few hours Our Lord, Who was accused of being too disinterested in politics, is charged with being too interested in it. The mob, with their prisoner, stopped outside Pilate’s doorsill, which marked the confines of a Roman house. Pilate, warned of their coming, went out to meet the accusers. Jesus and Pilate were face to face. Pilate looked at the Figure before him, silent and unmoved, crimsoned with His own blood, with livid red marks across His face, already the object of gross mistreatment before He had been condemned. Turning to the howling mob, Pilate asked: “What charge do you bring against this Man?” (John 18:29). If the charge was that He blasphemed by calling Himself God, Pilate would have only smiled. He had his own gods and each day sprinkled incense before them. What cared he about their divinities? There was one other charge that could be hurled at Christ—the opposite one, namely, that He was too political, that He was not divine enough, that He meddled in national affairs, that He was not patriotic. In answer to Pilate’s question, three charges were hurled: “We have found this man perverting our nation, and forbidding to give tribute to Caesar, and saying that He is Christ the king” (Luke 23:2). And so throughout history, these two contradictory charges have been leveled against the Person of Christ in His Body the Church. His Church was accused of not being political enough when it condemned Nazism and Fascism; it is accused of being too political when it condemns Communism. It is too unpolitical when it does not condemn a political regime that some other political systems dislike but which allows religious freedom; it is said to be too political when it condemns a political regime that completely suppresses all religion. What is the logic of these contradictory charges? Apparently, the world figures that the Church is something to be used, whose sole business is to make moral “Whoopee!” for certain kinds of politics. Whenever the spiritual and the political agree on a matter—as on Palm Sunday—then there is a moment of peace—but it is a false peace, which is the prelude to the violence of Good Friday. It is the second charge that needs specific consideration, namely, that the Church is interfering in politics. Is this true? It all depends upon what you mean by politics. If by interference in politics is meant using influence to favor a particular regime, party, or system that respects the basic God-given rights and freedom of persons, the answer is emphatically “No!” The Church does not interfere in politics. But if by interference in politics is meant judging or condemning a philosophy of life that is followed by the party, or the state, or the class, or the race the source of all rights, and that usurps the soul and enthrones party over soul’s conscience and denies those basic rights for which this war was fought, the answer is emphatically “Yes!” The Church must judge and does judge such a false philosophy. But when it does this, it is not interfering with politics, for such politics is no longer politics, but has entered the domain of theology. When a state sets itself up as absolute as God, when it claims sovereignty over the soul, when it destroys freedom of conscience and freedom of religion, then the state has ceased to be political and has begun to be a counter-Church. As long as politics is politics, and follows the moral laws, the Church has nothing to say. It is totally indifferent to any regime. The Church adapts itself to all governments on condition that they respect liberty of conscience and the rights of God. It is indifferent as to whether people choose to live under a monarchy, republic, democracy, or even a military dictatorship, provided these governments grant the basic freedoms. If by “interference in politics” is meant the interference by the clergy in the political realm of the state, the Church is unalterably opposed to it, for the Church teaches that the state is supreme in the temporal order. But when politics ceases to be politics and begins to be a religion, when it claims supremacy over the human soul, when it reduces the person to a grape for the sake of the line of collectivity, when it limits his destiny to be a servant of Moloch, when it denies both the freedom of conscience and the rights of God, when it competes with religion on its own ground, the immortal soul that is destined for God, then religion protests. And when it does, its protest is not against politics, but against a counter-religion that is anti-religious. A human body can adapt itself to the torrid heat of the equator or to the glacial cold of the North, but it cannot live without air. In like manner, the Church can adapt itself to every form of politics, but it cannot live without the air of freedom. Never before in history has the spiritual been so unprotected against the political. Never before has the political so usurped the spiritual. It was Christ Who suffered under Pontius Pilate; it was not Pontius Pilate who suffered under Christ. The grave danger today is not religion in politics, but politics in religion. For the first time in Christian history, politics has attempted to capture his soul, by every word that proceeds from the mouth of a dictator. For the first time in Western Christian civilization, the kingdom of anti-God has acquired political form and social substance, and stands over and against Christianity as a counter-Church with its own dogmas, its own scriptures, its own infallibility, its own hierarchy, its own visible head, its own missionaries, and its own invisible head—Satan. In certain countries today, religion exists only by the tolerance of a political dictator. Without actively persecuting the Church, it favors only to those who conspire against religion. The goal is to create an ideological uniformity by eliminating anyone who is opposed to that ideology, and bring about the mass organization of society on a purely secular and anti-religious basis. Culture today is becoming politicized. The modern state is extending dominance over areas outside its province—the family, education, and the soul. It is concentrating on influencing public opinion to place power in fewer and fewer hands, which becomes the more dangerous. History proves that it is not religion that has invaded the temporal sphere, but rather that jealous temporal rulers have invaded the spiritual arena. Sometimes these rulers were kings and princes, even so-called “Catholic defenders of the Faith.” Today they are dictators and political parties. But the problem is still the same—the invasion of the spiritual by the political. There is something alarming about that brief description of how Our Lord died. No other name is mentioned in the Creed except the name of one judge (Pontius Pilate)—Judas, Annas, and Caiphas are not mentioned. The earthly life of Our Lord is quickly passed over, but one significant detail is retained: “He suffered under Pontius Pilate.” This is a record not only of an historical fact, but it is also a prophecy of what will happen to Christ in His Church—namely, His Church, in these dark days of history, will go down to a seemingly final death and persecution, suffering under ‘Pontius Pilate’—the power of an omnipotent state. Politics has become so all-possessive of life. It may do religion no good to oppose a ‘state-religion’, for the modern state is armed and the Church is not. Religion may even be eliminated when the state rules, like Caiphas, that it is expedient that one man (Christ) die rather than the whole Jewish nation perish, which today will translate to “It is expedient that all the Christians should die, lest they become a thorn in the side of a One World Order and One World Religion.” We may hear from the lips of modern Pilates the words of power: “Do you not know that I have the power to condemn you?” But there will always come back to them the soft voice of Christ: “You would have no power unless it were given to you from above.” Maybe His children are being persecuted by the world in order that they might withdraw themselves from the world. Maybe the growth of atheism and totalitarianism is the consequence of our lack of zeal and devotion and the proof of our unfulfilled Christian duties. Not until we bear the marks of Christ will we be liberated in His victory. Maybe it is our loss of supernatural standards, our decline of the family, our want of reverence for others, our growing selfishness, that have made this state of affairs possible. Maybe we are to learn the hard way what our negligence and indifference and spiritual sloth has brought about! But whatever be the reason for these trying days, of this we may be certain: Christ’s Church will be attacked, scorned, and ridiculed, but it will never be destroyed. The enemies of God will never be able to dethrone the heavens of God, nor to empty the tabernacles of their Eucharistic Lord, nor to cut off all absolving hands, even though they may well devastate the Earth. |

Web Hosting by Just Host