| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

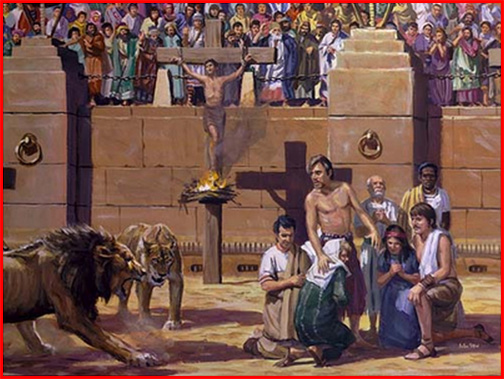

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE NAME OF THE SAINT YOU WISH TO VIEW

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

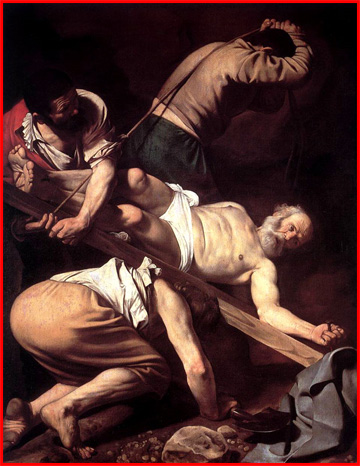

THE MARTYRDOM OF ST. PETER THE APOSTLE & FIRST POPE

scroll down for St. Paul of Tarsus

|

The final years of St. Peter and St. Paul at Rome are shrouded in uncertainties. The last historical Scriptural reference to Peter has him at the Council of Jerusalem, where he is seen supporting Paul’s mission to the Gentiles (Acts 15). The last reference we have of St. Paul, puts him at Rome awaiting trial before the emperor (Acts 28).

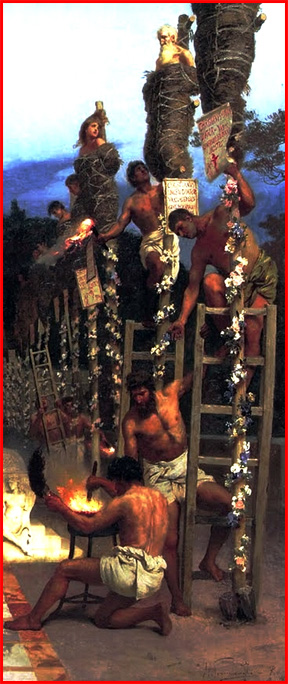

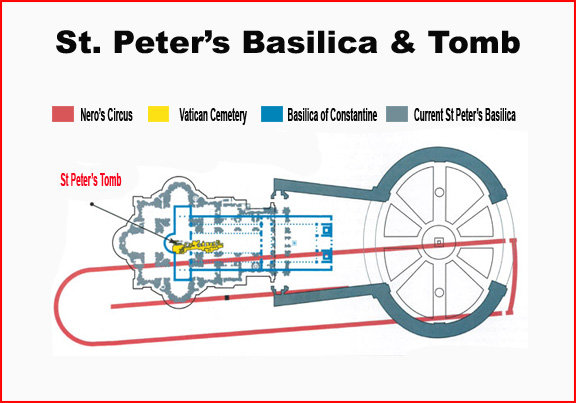

That both men were martyred there, most probably in the persecution of the emperor Nero, is accepted by most historians and church tradition. Twentieth-century archeology strongly strengthens this by identifying the places where each died and where each is buried. In addition to that, there is a wealth of material, passed down through the ages, which appeared in the years after the apostles died, that corroborates this.. The best known appears in the so-called work, the “Acts of Peter”, a third-century work that records that, when the Neronian persecution began, Peter’s friends entreated the Apostle to save his life by leaving the city. Peter at last consented, but on condition that he should go away alone. So Peter prepared to flee the city rather than face crucifixion with other Christians in the Hippodrome. However, as he was leaving Rome through the southern gate that led out onto the Appian Way, he saw Christ coming into Rome through the same gate. Falling down in adoration, Peter says to Him: “Quo vadis, Domine?” which means, “Where are you going, Lord?”Jesus, in what became known as the Quo Vadis Legend, replies. “To Rome, to be crucified again.” Peter then says to Him “Lord, do you want to be crucified again?” And the Lord said to him “Yes, I will again be crucified.” Peter said to Him “Lord, I will return and will follow Thee.” And at these words the Lord ascended into Heaven. Peter, coming to his senses, then understood that it was of his own (Peter’s) passion that Our Lord had been speaking, and that Our Lord would suffer with him. For, as St. Paul explains, when we suffer anything, we are making up for or filling up the sufferings that Christ did not have time to suffer during His brief spell on earth: “…fill up those things that are wanting of the sufferings of Christ, in my flesh, for His body, which is the Church” (Colossians 1:24). The Apostle Peter, once again humiliated, thinks again, turns, and goes back to the city with joy to meet the death which the Lord had signified that he should die. Peter, at his own request, he is crucified upside down, feeling himself unworthy of being crucified in the same way as his Master. Some Protestants even accept the story to be true. Regarding the authenticity of the story, the Protestant scholar Edmundson, in The Church in Rome in the First Century, says, "That it contains a story that is authentic in the sense of being based on events that really occurred is not improbable. The Peter described here is the Peter of the Gospels." Another Protestant, J.B. Lightfoot in his Ordination Addresses and Counsel to Clergy defended the authenticity of the story: "Why should we not believe it true? ... because it is so subtly true to character and because it is so eminently profound in its significance, we are led to assign to this tradition a weight which the external testimony in its favor would hardly warrant." What can we learn from this encounter? Well, the first thing that comes to mind are the words of God, spoken through Isaias, His Prophet: “For My thoughts are not your thoughts: nor your ways My ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are exalted above the earth, so are My ways exalted above your ways, and My thoughts above your thoughts” (Isaias 55:8-9). Peter’s way was not the Lord’s way—neither in the Garden of Gethsemane, when Peter tried to draw the sword and fight his way out of the trouble they were in; nor was Peter’s way the Lord’s way, when Peter said that he would not let Our Lord suffer, for which comment he received the rebuke of Our Lord: “Go behind Me, Satan, thou art a scandal unto Me: because thou savourest not the things that are of God, but the things that are of men” (Matthew 16:23). After His Resurrection, Our Lord foretold to Peter his future martyrdom, saying: “When thou shalt be old, thou shalt stretch forth thy hands, and another shall gird thee, and lead thee whither thou wouldst not” (John 21:18). Usually, when we speak to God about something happening in our live, we say something like: “Lord, be with me. Lord, go with me. Lord, help me with [ …fill in the blank].” We rarely say, “Lord, where are You going? I want to go with You. Take my hand and lead me where You want me to go.” Perhaps we need to write or type the words “Domine, quo vadis?” on a little piece of paper and tape it to our desk, kitchen counter, fridge, car dashboard, or anywhere and everywhere that we might be reminded that God’s ways are not our ways, and that God’s thoughts are not our thoughts. Then, every time we see that those words, we can say: “Where are You going today, Lord? I want to go with you.” The New Testament only records the death of the Apostle St. James, so most other knowledge of the deaths of the other Apostles and disciples relies on tradition. As for St. Peter’s death, there are various accounts and stories that might shed some light upon his martyrdom. Traditionally, the year of his martyrdom was thought to be 67 AD. Recent research, conducted from 1963 to 1968, under the direction of Margherita Guarducci, believes the death of St. Peter to have occurred in 64 AD, on October 13th, during the festivities of the “dies imperii” – the imperial anniversary day of Emperor Nero. These festivities are known to have taken place three months after the disastrous fire that destroyed the city of Rome. Emperor Nero blamed the fire on the Christians. The dies imperii took placed exactly ten years after Nero came to the throne and was accompanied by much bloodshed. The ancient historian Flavius Josephus describes ways the Roman soldiers amused themselves by crucifying criminals in different positions. The position attributed to the crucifixion of St. Peter is plausible on account of the Roman tendency to improvise their tortures—tradition says St. Peter requested not to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus, as he was not worthy to die in the same way as his Lord. So the Roman soldiers crucified him upside down. More gruesome details concerning the martyrdom of St. Peter have circulated for ages; including that it took Peter three days to die upside down. Death in the ordinary position of crucifixion is thought to cause suffocation in certain positions (though modern research disputes this), but one does not suffocate when hanging upside down. There are stories that the soldiers attempted to burn St. Peter, while he was crucified on his cross, but this failed, and he did not die from the burns. After three days he is said to have been beheaded while hanging upside down. Pope Clement of Rome, in his Letter to the Corinthians (chapter 5), wrote, "Let us take the noble examples of our own generation. Through jealousy and envy the greatest and most just pillars of the Church were persecuted, and came even unto death… Peter, through unjust envy, endured, not one, or two but many labors, and at last, having delivered his testimony, departed unto the place of glory due to him." St. Peter's place of execution is believed to be in the Neronian Gardens (now located in the Vatican City) where, generally, the gruesome scenes of the Neronian persecutions took place. The historian Eusebius, a contemporary of the emperor Constantine, wrote that St. Peter “came to Rome, and was crucified with his head downwards,” though he attributes this information to the much earlier theologian, Origen, who died around 254 AD. Peter’s place and manner of death are also mentioned by Tertullian (c. 160-220) in Scorpiace, where the death is said to take place during the Christian persecutions by Nero. Tacitus (56-117) describes the persecution of Christians in his Annals, though he does not specifically mention Peter. “They were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt.” Furthermore, Tertullian says these events took place in the imperial gardens, near the Circus of Nero. No other area would have been available for public persecutions, after the Great Fire of Rome destroyed the Circus Maximus and most of the rest of the city in the year 64 AD. This account is supported by other sources. In The Passion of Peter and Paul, dating to the fifth century, the crucifixion of Peter is recounted. Then it adds, “Holy men ... took down his body secretly and put it under the terebinth tree near the Naumachia, in the place which is called the Vatican.” The place called Naumachia would be an artificial lake within the Circus of Nero, where naval battles were reenacted for an audience. The place called “Vatican” was, at the time, a hill next to the complex and also next to the Tiber River, featuring a cemetery of both Christian and pagan tombs. Catholic tradition holds that Peter's inverted crucifixion occurred at the spot now occupied by the Clementine Chapel in the grottoes of Saint Peter's Basilica, with the burial in Saint Peter's tomb nearby. In the 1960s, excavations beneath St Peter's Basilica were re-examined, and the bones of a male person were identified. A forensic examination found them to be a male of about 61 years of age from the 1st century. This caused Pope Paul VI in 1968 to announce them most likely to be the relics of Apostle Peter. On November 24, 2013, Pope Francis revealed these relics of nine bone fragments for the first time in public during a Mass celebrated in St. Peter's Square. Saint Peter’s tomb is a site under St. Peter’s Basilica that includes several graves and a structure said by Vatican authorities to have been built to memorialize the location of St. Peter’s grave. St. Peter’s tomb is near the west end of a complex of mausoleums that date between about 130 AD and 300 AD. The complex was partially torn down and filled with earth to provide a foundation for the building of the first St. Peter’s Basilica during the reign of Constantine I in about 330 AD. Though many bones have been found at the site of the 2nd-century shrine, as the result of two campaigns of archaeological excavation, Pope Pius XII stated in December, 1950, that none could be confirmed to be Saint Peter’s with absolute certainty. However, following the discovery of further bones and an inscription, on June 26, 1968, Pope Paul VI announced that the relics of St. Peter had been identified. As St. Paul was executed on the same day (most likely by beheading) it is believed the two Apostles lay in the same grave for a period of time. Remains of both were said to have been moved to where the Church of St. Sebastian now stands, as a means of protecting them during the Valerian persecutions of 258 AD. Both remains were later restored to their former resting places before Constantine the Great erected the Basilica, over the grave of St. Peter, at the foot of the Vatican Hill. Today, the bones of St. Peter are enshrined beneath the high altar of St. Peter's Basilica. |

THE MARTYRDOM OF ST. PAUL, THE APOSTLE TO THE GENTILES

|

Arrival in Rome

Around 61 A.D. Paul arrived in Rome to undergo judgment. He had been imprisoned in Rome after being accused by some Jews of having brought Gentiles into the Temple. Paul’s first gesture in the capital city of the Empire and also his last words, documented in the Acts of the Apostles, were aimed at launching – once more – an appeal to the Jews. He did so in the same manner as in his earlier Letter to the Romans: “For I am not ashamed of the Gospel. It is the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes: for Jew first, and then Greek” (Romans 1:16). In this way, at the conclusion of his mission, the man whom the Lord had chosen as Apostle to the Nations did not want to forget even the “least brothers of mine” (Matthew 25:40), “for it is on account of the hope of Israel that I wear these chains” (Acts 28:20). He launched his final and vibrant appeal to the “conversion” of his people, to the radical change of life he had come to know. In Christ, God’s Covenant is now open to all people. His final words did not mean the end of Paul, for on the contrary, Christianity and the Good News spread to all the ends of the earth due to his great witness to the Risen One, in whose image Paul became a “Light of the Nations” (Isaias 49:6; Acts 13:47). First Trial—Acquittal—Second Trial—Death He appealed to Caesar on the grounds of being a Roman citizen, and as a result was allowed to remain in Rome to be tried instead of being sent to Jerusalem. His trial is assumed to have ended in his acquittal sometime around 65 after being held for several years, at which point it seems he went to Macedonia. Upon his return to Rome, under the Emperor Nero’s persecution of Christians, whom he had blamed for the destructive fire of Rome, Paul was arrested once again, imprisoned, tortured severely and ordered to have his head cut off.. Because he was a Roman citizen, he received a different punishment than some other criminals of the time (who were often crucified), and was beheaded between 66-68 AD at Aquae Salviae, which is now known as Tre Fontane. Account of Paul’s Martyrdom It is commonly thought that Peter and Paul were executed on the same day. Paul’s martyrdom is recounted for the first time in the apocryphal Acts of Paul, written towards the end of the second century. They say that Nero condemned him to death by beheading, an order which was carried out immediately (cf. 9: 5). The date of his death already varies in the ancient sources which set it between the persecution unleashed by Nero himself after the burning of Rome in July 64 and the last year of his reign, that is, the year 68 (cf. Jerome, De viris ill. 5, 8). One version of his martyrdom states that it occurred at the Acquae Salviae, on the Via Laurentina, and that after he was beheaded, his head bounced three times, giving rise to a source of water each time that it touched the ground, which is why, to this day, the place is called the "Tre Fontane" [three fountains] (Acts of Peter and Paul by the Pseudo-Marcellus, fifth century). Another account, which is in harmony with the ancient account of the priest Gaius and Christian tradition, adds the fact that Paul’s body was buried two miles away from the place of his martyrdom, in a vineyard, in the sepulchral area along the Ostian Way, which was part of a pre-existent burial place, owned by a Roman Christian, named Lucina, who was also a devout Christian. The ancient account states that his burial not only took place "outside the city... at the second mile on the Ostian Way", but more precisely "on the estate of Lucina", who was a Christian matron (Passion of Paul by the Pseudo-Abdias, fourth century). Even though he was a Christian, it was possible to bury the Apostle Paul in a Roman necropolis, due to his Roman citizenship. Another account says that while St. Paul was passing along with the executioner, he met a damsel who was a kinswoman of the Emperor Nero, and who had believed through him. She walked along with St. Paul, weeping, to where they carried out the sentence. He comforted her and asked her for her veil. He wrapped his head with the veil, and asked her to return back. The executioner cut off his head and left it wrapped in the veil of the young girl, and that was in the year 67 A.D. The young girl met the executioner on his way back to the Emperor, and asked him about Paul and he replied, "He is lying where I left him and his head is wrapped in your veil." She told him, "You are lying, for he and Peter have just passed by me, they were arrayed in the apparel of kings, and had crowns decorated with jewels on their heads, and they gave me my veil, and here it is." She showed it to the executioner, and to those who were with him. They marveled, and believed in the Lord Christ and were converted to the Faith. Shrine to St. Paul Shortly thereafter, his tomb would become a place of worship and veneration. Upon it was erected a cella memoriae or tropaeum, namely a memorial, where during the first centuries of persecution many of the faithful and pilgrims would go to pray, drawing the strength necessary to carry out the work of evangelization of this great missionary. The shrine grew and grew, before the Emperor Constantine, who had ended the persecution of Christians and allowed a freedom of worship, built a first church, which was consecrated as a basilica in 324. Then, between the fourth and fifth centuries it was considerably enlarged by the Emperors Valentinian II, Theodosius and Arcadius. The present-day Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls was built in the 19th century, after a fire destroyed it in 1800. THE TOMB OF ST. PAUL The Marble Tombstone Around 5 feet below the present Papal Altar lies a marble tombstone (7 feet x 4 feet), bearing the Latin inscription PAULO APOSTOLO MART (Paul Apostle Martyr). It is composed of various pieces. On the piece where PAULO is written there are three holes, a round and two square ones. Linen cloths can be pushed through the holes, so as to touch whatever remains are in the sacrophagus. In ancient times, these holes would be used for the pouring of perfumes into the sacrophagus. The Sarcophagus or Body Encasement The tombstone is above a massive sarcophagus, measuring over 8 feet long, 4 feet wide and 3 feet high, that the “Altars of Confession” were later placed. During recent work in the Basilica, a large window-like opening was made just below the Papal Altar, in order to allow the faithful to see the Apostle’s tomb. Vatican archaeologists uncovered the tomb in 2006 in a crypt under the basilica and said, in view of the fact that this tomb was positioned exactly underneath the epigraph 'Paulo Apostolo Mart.' (Paul the Apostle and Martyr), at the base of the cathedral's main altar, was sufficient and conclusive proof that it was the apostle's sarcophagus. CONCLUSION The figure of St Paul towers far above his earthly life and his death; in fact, he left us an extraordinary spiritual heritage. He too, as a true disciple of Christ, became a sign of contradiction. Like so many other martyrs, he received a gradual preparation in ever-increasing suffering throughout his life. The Acts of the Apostles tell us of the many sufferings that God had prepared for Paul—for God had told Ananias: “This man is to Me a vessel of election, to carry My name before the Gentiles and kings, and the children of Israel. For I will show him how great things he must suffer for My Name's sake” (Acts 9:15-16). St. Paul, himself, gives us a tiny peephole into some of many great sufferings God’s Providence had shown him at that point in time: Comparing himself to the Apostles, St. Paul says: “They are Hebrews: so am I. They are Israelites: so am I. They are the seed of Abraham: so am I. They are the ministers of Christ (I speak as one less wise). I am more: in many more labors; in prisons more frequently; in stripes above measure; in deaths often. Of the Jews five times did I receive forty stripes, save one. Thrice was I beaten with rods; once I was stoned; thrice I suffered shipwreck, a night and a day I was in the depth of the sea. In journeying often; in perils of waters; in perils of robbers; in perils from my own nation; in perils from the Gentiles; in perils in the city; in perils in the wilderness; in perils in the sea; in perils from false brethren. In labor and painfulness; in much watchings; in hunger and thirst; in fastings often; in cold and nakedness. Besides those things which are without: my daily instance, the solicitude for all the churches” (2 Corinthians 11:22-28). This is what Our Lord means by the cross, that He expects us take up daily in our quest for Heaven: "If any man will come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow Me" (Luke 9:23). "He that loveth father or mother more than Me, is not worthy of Me; and he that loveth son or daughter more than Me, is not worthy of Me. And he that taketh not up his cross, and followeth Me, is not worthy of Me. He that findeth his life, shall lose it: and he that shall lose his life for Me, shall find it" (Matthew 10:37-39). |

Web Hosting by Just Host