| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

PART ONE : THE FOUNDATIONS & ANCESTRY OF THE ROSARY

|

Devotions Grow Gradually

Devotions, like civilizations, grow and are gradually modified over time. They take ideas from the past and modify them by adding something desirable to them. We see a classic example of that in the history of the Sacrifice of the Mass, how, over time, it was modified and beautified, while ever retaining the essential parts. Mary had parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and so on, all of whom contributed in some way to the future beliefs and attitudes that Mary would hold, and even the circumstances and geographical location in which Mary would live. Similarly, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass borrowed much from the Jewish ritual of worshiping God, since the first Christians were mainly Jews. Yet the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass grew in its style and prayers and rubrics over the course of the centuries. It was especially in the Middle Ages that many parts of the Mass were embellished and added to. The Mass at the time of the Apostles was essentially the same as the Mass of the Middle Ages, but as regards non-essential parts of the Mass, it had been greatly embellished and beautified during the Middle Ages. Likewise, the Rosary has borrowed from ancient customs and added a Marian flavor to them. We will have a look at some of those customs to better understand why the Rosary is what it is, and better understand how it came to evolve and enrich the the spiritual life of the Church. Devotions, like civilizations, grow and are gradually modified over time. They take ideas from the past and modify them by adding something desirable to them. We see a classic example of that in the history of the Sacrifice of the Mass, how, over time, it was modified and beautified, while ever retaining the essential parts. Mary had parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and so on, all of whom contributed in some way to the future beliefs and attitudes that Mary would hold, and even the circumstances and geographical location in which Mary would live. Similarly, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass borrowed much from the Jewish ritual of worshiping God, since the first Christians were mainly Jews. Likewise, the Rosary has borrowed from ancient customs and added a Marian flavor to them. We will have a look at some of those customs to better understand why the Rosary is what it is, and better understand how it came to evolve and enrich the the spiritual life of the Church. Counting Devices Throughout History It is obvious that whenever any prayer has to be repeated a large number of times, then some recourse is likely to be had to some mechanical apparatus that lessens the difficulty of counting upon the fingers. In almost all countries, we can find these devices that are similar in nature to prayer-counters or our modern-day Rosary beads. ► In ancient Nineveh a sculpture has been found thus described by Lavard in his “Monuments” (I, plate 7): “Two winged females standing before the sacred tree in the attitude of prayer; they lift the extended right hand and hold in the left a garland or Rosary.” ► The Desert Father would use pebbles to count the number of prayers that they had said. ► Similarly, beside the mummy of a Christian ascetic, Thaias, of the fourth century, recently disinterred at Antinöe in Egypt, was found a sort of cribbage-board with holes, which has generally been thought to be an apparatus for counting prayers, of which Palladius and other ancient authorities have left us an account. ► A certain Paul the Hermit, in the fourth century, had imposed upon himself the task of repeating three hundred prayers, according to a set form, every day. To do this, he gathered up three hundred pebbles and threw one away as each prayer was finished. ► At an early date, among the monastic orders, the practice had established itself of not only offering Masses, but of saying vocal prayers as a suffrage for their deceased brethren. For this purpose the private recitation of the 150 psalms, or of 50 psalms, the third part, was constantly enjoined. Already in 800 AD, we read of an agreement between the moansteries of St. Gall and Reichenau, that, for each deceased brother, all the priests should say one Mass and also fifty psalms. ► Mohammedans had a bead-string, consisting of 33, 66, or 99 beads, and used for counting devotionally the names of Allah, which has been in use for many centuries. ► Marco Polo, visiting the King of Malabar in the thirteenth century, found to his surprise that that monarch employed a rosary of 104 (? 108) precious stones to count his prayers. ► St. Francis Xavier and his companions were equally astonished to see that rosaries were universally familiar to the Buddhists of Japan. ► Among the monks of the Greek Church we hear of a cord with a hundred knots, which was used to count genuflections and signs of the cross. ► Similarly among the Knights Templar, whose rule dates from about 1128, the knights, who could not attend choir, were required to say the Lord’s Prayer 57 times in all, and, on the death of any of the brethren, they had to say the Pater Noster a hundred times a day for a week. To count these accurately there is every reason to believe that already in the eleventh and twelfth centuries a practice had come in of using pebbles, berries, or discs of bone threaded on a string. It is in any case certain that the Countess Godiva of Coventry (c. 1075), left by will to the statue of Our Lady in a certain monastery, “the circlet of precious stones which she had threaded on a cord, in order that by fingering them, one after another, she might count her prayers exactly.” Another example seems to occur in the case of St. Rosalia (1160), in whose tomb similar strings of beads were discovered. Even more important is the fact that such strings of beads were known throughout the Middle Ages—and in some Continental tongues are known to this day—as “Paternosters”. The evidence for this is overwhelming and comes from every part of Europe. Already in the thirteenth century the manufacturers of these articles, who were known as “paternosterers”, almost everywhere formed a recognized craft guild of considerable importance. The “Livre des métiers” of Stephen Boyleau, for example, supplies full information regarding the four guilds of patenôtriers in Paris in the year 1268, while the street, Paternoster Row, in London, still preserves the memory of the street in which their English craft-fellows congregated. Now the obvious conclusion is that an appliance which was always and everywhere called a “Paternoster”, had, at least originally, been designed for counting Our Fathers. This deduction, drawn out and illustrated with much learning by Father T. Esser, O.P., in 1897, becomes a practical certainty when we remember that, it was only in the middle of the twelfth century that the Hail Mary came at all generally into use as a formula of devotion. It is morally impossible that Lady Godiva’s circlet of jewels could have been intended to count Ave Marias. Hence there can be no doubt that the strings of prayer-beads were called “paternosters” because for a long time they were principally employed to number repetitions of the Lord’s Prayer. This lays the foundation and framework upon which the Ave Marias would be placed. We will look at that development in our next article. |

PART TWO : THE SEEDLINGS OF THE ROSARY

|

The Beads and the Prayers

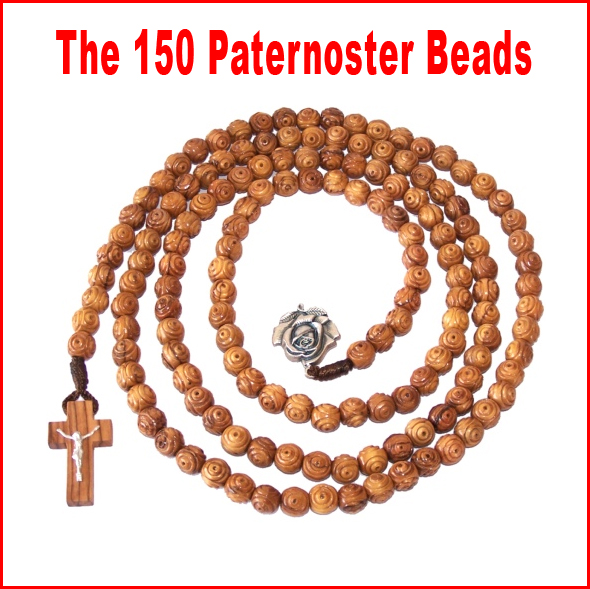

Instruments for counting date back well before the time of Christ, to Ancient Egypt and beyond. The abacus was one such instrument. The word Abacus is derived from the Greek word abax, meaning “calculating board” or “calculating table”. The first Chinese Abacus was invented around 500 B.C. The abacus, as we know it today, was used in China around 1300 A.D. Yet people would count with whatever was readily available—whether it be carving notches in wood, or using objects. As the first article began to show, pebbles, stones, knotted ropes, etc.—have been used from the earliest times in order to keep count of prayers. Among the monks of the Greek Church we hear of the kombologion, or komboschoinion, a cord, with a hundred knots, used to count genuflections and signs of the cross. Similarly, beside the mummy of a Christian ascetic, Thaias, of the fourth century, recently disinterred at Antinöe in Egypt, was found a sort of cribbage-board with holes, which has generally been thought to be an apparatus for counting prayers, of which Palladius and other ancient authorities have left us an account. St. Paul the Hermit, in the fourth century, had imposed upon himself the task of repeating three hundred prayers, according to a set form, every day. To do this, he gathered up three hundred pebbles and threw one away as each prayer was finished. It is probable that other ascetics (hermits, desert fathers, etc.) who also numbered their prayers by the hundreds, also adopted some similar means of keeping count. When we read the papal privilege, addressed to the monks of St. Apollinaris in Classe, requiring them, in gratitude for the pope's benefactions, to say Kyrie Eleison (Lord have mercy) three hundred times, twice a day, then one would guess that some counting apparatus must have been necessarily used for the purpose. But there were other prayers to be counted, more closely connected with the Rosary than the Kyrie Eleisons. At an early date, among the monastic orders, the practice had established itself, not only of offering Masses, but of saying vocal prayers as a suffrage for their deceased brethren. For this purpose the private recitation of the 150 psalms, or of 50 psalms, the third part, was constantly required for the soul of the deceased. Already in A.D. 800 we learn from the agreement between the monasteries of St. Gall and Reichenau, that, for each deceased brother, all the priests should say one Mass and also fifty psalms. A charter in Kemble prescribes that each monk is to sing two fifties (of psalms) for the souls of certain benefactors, while each priest is to sing two Masses and each deacon to read two Passions. But as time went on, and the conversi, or lay brothers, most of them quite illiterate, became distinct from the choir monks, it was felt that they also should be required to substitute some simple form of prayer in place of the psalms to which their more educated brethren were bound by rule. Thus we read in the “Ancient Customs of Cluny”, collected by Udalrio in 1096, that when the death of any brother at a distance was announced, every priest was to offer Mass, and every non-priest was either to say fifty psalms or to repeat fifty times the Pater Noster (Our Father). The first prayer Christians recited on prayer beads was the Our Father (in Latin, Pater Noster). For those who could not read, reciting 150 paternosters was regarded as equivalent to reciting the 150 Psalms. This alternative “Psalter” appears in the Rule of St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226), a contemporary of St. Dominic (1170-1221). The beads used for counting were called Paternoster Beads: usually a string of 10, 50 or 150 beads, with or without dividing markers. Similarly among the Knights Templar, whose rule dates from about 1128, the knights who could not attend prayers in community in the church, were required to say the Pater Noster (Our Father) 57 times in all, and, on the death of any of the brethren, they had to say the Pater Noster (Our Father) a hundred times each day for an entire week. Already in the thirteenth century the manufacturers of these articles, who were known as “paternosterers”, almost everywhere formed a recognized craft guild of considerable importance. The “Livre des métiers” of Stephen Boyleau, for example, supplies full information regarding the four guilds of Patenôtriers (chaplet makers) in Paris in the year 1268, while a street in London, till this day, is called Paternoster Row, still preserves the memory of the street in which their English craft-fellows congregated. When the Ave Maria (Hail Mary) came into use, it followed the fashion of the Pater Noster (Our Father) of repeating it many times in succession, accompanied by genuflections or some other external act of reverence. Devout people began to create variations on this devotional practice, adding an Ave Maria (Hail Mary) or Gloria Patri (Glory be) after each Pater Noster (Our Father) or simply saying 150 Aves. This was the creation of “St. Mary’s Psalter” or the “Psalter of Mary”—which was simple man’s ‘Book’ of the 150 Psalms. An account is given of St. Albert (died 1140) by his contemporary biographer, who tells us: “A hundred times a day he bent his knees, and fifty times he prostrated himself raising his body again by his fingers and toes, while he repeated at every genuflection: ‘Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee, blessed art thou amongst women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb’.” This was the whole of the Hail Mary as then said, and the fact of all the words being set down, rather implies that the formula had not yet become universally familiar. |

PART THREE : OUR LADY GIVES THE ROSARY TO ST. DOMINIC

|

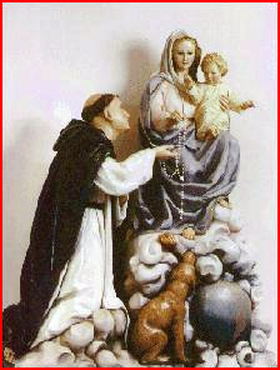

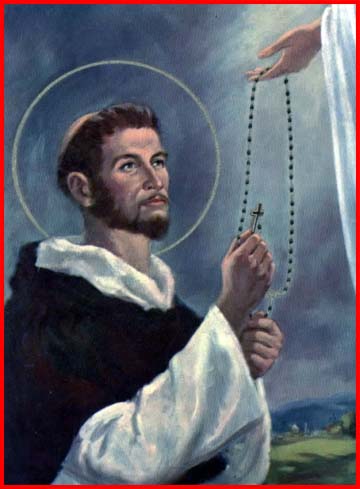

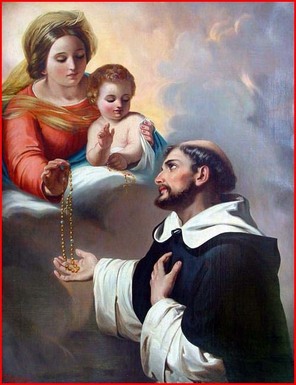

The Rosary from Heaven

In the year 1214 Saint Dominic, the founder of the Order of Preachers, was in anguish because he was failing in his attempt to convert the Albigensian Cathar heretics. St. Dominic attributed this to the deepness and gravity of sinfulness of the heretics and the poor example of Catholics. He went alone in to the forest and wept and prayed continuously for three days to appease the anger of Almighty God. He flogged his body and scourged his flesh. From the fasting, pain, and exhaustion, he passed in to a coma. St. Louis de Montfort explains what happened. In his book, The Secret of the Rosary, St. Louis, in the chapters entitled the "Second Rose" and "Third Rose", explains the origin of the Rosary and the role that St. Dominic plays in its final format, as we know it today: “Since the Holy Rosary is composed, principally and in substance, of the Prayer of Christ and the Angelic Salutation, that is, the Our Father and the Hail Mary, it was without doubt the first prayer and the first devotion of the faithful and has been in use all through the centuries, from the time of the apostles down to the present. But it was only in the year 1214, however, that Holy Mother Church received the Rosary in its present form and according to the method we use today. It was given to the Church by Saint Dominic who had received it from the Blessed Virgin as a powerful means of converting the Albigensians and other sinners. “I will tell you the story of how he received it, which is found in the very well-known book, ‘De Dignitate Psalteri’ by Blessed Alan de la Roche. Saint Dominic, seeing that the gravity of people’s sins was hindering the conversion of the Albigensians, withdrew into a forest near Toulouse where he prayed unceasingly for three days and three nights. During this time he did nothing but weep and do harsh penances in order to appease the anger of Almighty God. He used his discipline so much that his body was lacerated, and finally he fell into a coma. “At this point Our Lady appeared to him, accompanied by three angels, and she said: ‘Dear Dominic, do you know which weapon the Blessed Trinity wants to use to reform the world?’ “‘Oh my Lady,’ answered Saint Dominic, ‘you know far than I do because next to your Son Jesus Christ you have always been the chief instrument of our salvation.’ “Then Our Lady replied: ‘I want you to know that, in this kind of warfare, the battering ram has always been the Angelic Psalter which is the foundation stone of the New Testament. Therefore if you want to reach these hardened souls and win them over to God, preach my Psalter.’ “So he arose, comforted, and burning with zeal for the conversion of the people in that district he made straight for the Cathedral. At once unseen angels rang the bells to gather the people together and Saint Dominic began to preach. At the very beginning of his sermon an appalling storm broke out, the earth shook, the sun was darkened, and there was so much thunder and lightning that all were very much afraid. Even greater was their fear when looking at a picture of Our Lady, exposed in a prominent place, they saw her raise her arms to Heaven three times to call down God’s vengeance upon them if they failed to be converted, to amend their lives, and seek the protection of the Holy Mother of God. God wished, by means of these supernatural phenomena, to spread the new devotion of the Holy Rosary and to make it more widely known. At last, at the prayer of Saint Dominic, the storm came to an end, and he went on preaching. So fervently and compelling did he explain the importance and value of the Holy Rosary that almost all the people of Toulouse embraced it and renounced their false beliefs. In a very short time a great improvement was seen in the town; people began leading Christian lives and gave up their former bad habits.” (St. Louis de Montfort, The Secret of the Rosary). Dominic experienced an apparition of Blessed Mother Mary while in the coma, which forever links Saint Dominic and the Rosary. The Immaculate Mary with three angels appeared and asked St. Dominic, “Dear Dominic, do you know which weapon the Blessed Trinity wants to use to reform the world? … I want you to know that, in this kind of warfare, the battering ram has always been the Angelic Psalter which is the foundation stone of the New Testament. Therefore if you want to reach these hardened souls and win them over to God, preach my Psalter” The “Angelic Salutation” is the “Hail Mary” prayer and the “Psalter” is made up of the 150 Psalms. Thus, she wanted 150 Hail Marys—which is what the Holy Rosary is—15 decades of 10 Hail Marys with 15 corresponding mysteries to contemplate. Shortly after this apparition St. Dominic preached the Holy Rosary to the unconverted Albigenisan heretics. To modify the Paternoster (150 Our Father’s) and in compliance with the instruction in the apparition, the design of the Saint Dominic Rosary came in to being. He set apart fifteen mysteries of the rosary, grouped them in to three sets of five decades each. The groupings were designated as Joyous Mysteries, Sorrowful Mysteries and Glorious Mysteries. This design helped the Albigensian heretics to better understand and to imitate the virtuous life of our Lord Jesus Christ and the Immaculate and Blessed Mary. The Claim Against Mary Giving the Rosary There are some Modernists and Rationalist and Liberals who do not believe that Our Lady gave the Holy Rosary to St. Dominic. Let’s examine the Modernist argument against the Marian origin of the Holy Rosary. Some moderns hold that the traditional account depicting Mary giving the Rosary directly to St Dominic is a pious etiological myth. This myth, they say, allegorizes the origin of the Rosary with the Dominican order. The “true” story, the moderns claim, is that the Rosary was a gradual and historical development. They say that since the Dominicans popularized the Rosary devotion, the traditional myth personifies the Dominicans in the person of Dominic. So then, the moderns allege that the Blessed Virgin Mary did not directly give the Rosary to Dominic. Rather, the Dominicans popularized the devotion and so Mary “sort of” gave the Rosary to the world through the “sons of Dominic,” i.e. the Dominicans. These moderns observe that the practice of praying Our Father’s and Hail Mary’s on beads is a practice that predates Saint Dominic, and that this “Rosary” gradually evolved. This fact, they claim, further substantiates the conclusion that the Holy Rosary is not a revealed gift given directly to Dominic by the Blessed Virgin Mary herself. While it is certain that many (East and West) prayed on beads prior to Saint Dominic, the original claim is that the Holy Rosary as a collection of 150 Hail Mary’s with the 15 Mysteries (Joyful, Sorrowful, Glorious) was literally and historically given to Saint Dominic by the Immaculate Mother herself. (1) Moderns claim that the tradition of Mary giving the Rosary to Dominic is an etiological myth. (2) It is true: praying Our Fathers and Hail Marys on beads predates Saint Dominic (in fact, the word “bead” comes from the word “bid” meaning “pray” or “ask”). (3) The key to this debate is realizing that the Holy Rosary is not merely praying on beads, but praying the 150 Hail Mary’s with the 15 corresponding mysteries. It is this special combination of 150 Hail Mary’s with the 15 mysteries that constitutes the Rosary and it is this “combination” of vocal and mental prayer that Mary gave to St Dominic. What does the Catholic Church say? Pope Leo XIII, in his encyclical Octobri Mense, teaches that the Rosary does in fact have its origin from the Immaculate Mary herself “by her command and counsel” to Saint Dominic. Pope Leo XIII teaches: “That the Queen of Heaven herself has granted a great efficacy to this devotion is demonstrated by the fact that it was, by her command and counsel, instituted and propagated by the illustrious St. Dominic, in times particularly dangerous for the Catholic cause.” Pope Leo XIII also clarified that this original institution of the Holy Rosary by Mary included the Joyful, Sorrowful, and Glorious Mysteries, which he calls the “great mysteries of Jesus and Mary, their joys, sorrows, and triumphs.” In his Supremi Apostolatus Officio, Pope Leo XIII again confirms the supernatural origin of the Holy Rosary of Saint Dominic: “Great in the integrity of his doctrine, in his example of virtue, and by his apostolic labors, he proceeded undauntedly to attack the enemies of the Catholic Church, not by force of arms, but trusting wholly to that devotion which he was the first to institute under the name of the Holy Rosary, which was disseminated through the length and breadth of the Earth by him and his pupils. Guided, in fact, by divine inspiration and grace, he foresaw that this devotion, like a most powerful warlike weapon, would be the means of putting the enemy to flight, and of confounding their audacity and mad impiety. Such was indeed its result. Thanks to this new method of prayer—when adopted and properly carried out as instituted by the Holy Father St. Dominic—piety, faith, and union began to return, and the projects and devices of the heretics to fall to pieces.” The tradition is further confirmed by the apparition of the Immaculate Mary to Blessed Alan de la Roche: “My son, you know perfectly the ancient devotion of my Rosary, preached and diffused by your Patriarch and my Servant Dominic and by his spiritual sons, your religious brothers. This spiritual exercise is extremely agreeable to both my Son and to me, and most useful and holy for the faithful. When my Servant Dominic started to preach my Rosary … the reform in the world reached such heights that it seemed that men were transformed into angelic spirits and that Angels had descended from Heaven to inhabit the earth. … No one was considered a true Christian unless he had my Rosary and prayed it. … The prestige of the Holy Rosary was such that no devotion was or is more agreeable to me after the august Sacrifice of the Mass.” |

PART FOUR : THE HOLY ROSARY GOES TO WAR!

|

The role of the Rosary in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 (see here) is well known, yet few people are aware of another much earlier battle in 1213, the very first battle in which Our Lady’s Rosary was invoked to beseech victory for the forces fighting for the preservation of Christendom, by no less a personage than St. Dominic himself. I speak of the battle of Muret.

The Battle of Muret, fought in the year 1213, was perhaps the single most important battle in the long series of maneuvers we refer to today as the “Albigensian Crusade.” Though the final capitulation of the region would not come for another 16 years, it is certain that without Muret, that capitulation would never have occurred. The situation, essentially, was this: the heresy of the Manicheans, which Augustine had been deluded by in the 4th century, survived in various backwater places, and re-entered Europe through Bulgaria, where its adherents soon spread into Italy and southern France, taking the name “Albigensians,” from the city of Albi where they were numerous. Simon IV de Montfort was the leader of the Albigensian Crusade to destroy the Cathar (Albigensian) heresy and incidentally to join the southern area Languedoc to the crown of France. He invaded Toulouse, a little to the northeast of Muret, and exiled its count, Raymond VI. Count Raymond sought assistance from his brother-in-law, King Peter (Pedro) II of Aragon, who felt threatened by Montfort’s conquests in Languedoc. He decided to cross the Pyrenees and deal with Montfort at Muret. Southern France was always less Catholic than other places, due to the prosperous and laid-back Mediterranean culture which prevailed there, the influence of the Moslem to the south in Spain, and the influence of the Jew, who found a society more interested in pursuing courtly love and spawning troubadours, than in practicing devoutly the Catholic religion. The clergy had also entered in on the loose mode of living as well, and set very few pious examples to inspire their flocks, either. It is little wonder, then, that in this particular region, under the leadership of the Count of Toulouse, whose political ambitions tended towards independence from his nominal sovereign, the “King of Paris” in the north, heresy should rear its ugly head. Feudal relations in Occitania (the southern regions of modern-day France) were complicated. The kings of Aragon were among the major overlords in the region. Most of their lands north of the Pyrenees were held by powerful vassals such as the counts of Toulouse. While King Peter II of Aragon — also known as Peter the Catholic — did not support the Cathars, most of his vassals did. Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, who was not only Peter’s vassal but also his brother-in-law, assumed command of the joint Occitan armed forces. Its head was ugly, indeed. The Albigensians had a long and peculiar set of tenets, believing, as the Zoroastrians of Persia do, in a form of dualism, where created matter, having been allegedly brought into existence by the “evil” principle, is to be shunned, while the “good” principle is the realm of the spirit. (Ironically, we can see echoes of this teaching in Protestantism and its tendency to puritanism, which endures even today). In concrete terms, they rejected the legitimacy of oaths, holding them sinful: as medieval society was built upon such oaths, of freeholder to gentleman, knight to lord, lord to king, king to God, rejection of them was essentially anarchic, and tended to the dissolution of society. Furthermore, their abhorrence of the flesh manifested itself in a demonic form of religion where the “followers” were permitted to live lax and immoral lives, doing whatever they wished, with the sole promise that upon their deathbed they would receive the sole Albigensian sacrament, the “consolamentum,” and become one of the “Cathari,” meaning, “the pure.” Cathari (those who chose to receive the consolamentum earlier,) were essentially the priests of the religion, putting on a show of holiness and living ostensibly austere lives with many particular rules and observances: in reality, it is said that their private habits were decidedly immoral. To the Albigensian, human life was a great evil, because it entailed the shackling of the soul (“good”) to the flesh (“evil.”) Therefore, abortion, contraception, child-murder, and suicide were “virtuous.” Indeed, a layman receiving the consolamentum upon his deathbed was often killed afterwards, either outright, by suffocation, or by starvation, in a ritual known as the “endura,” to insure that he would not recover and subsequently fall from the ranks of the “pure,” unaccustomed as he was to keeping the rules of the Cathari. In practice, therefore, the heresy was not only a vile mockery of Catholic teachings, but a twisted and demonic influence, which spread immorality and death, and threatened to destroy Catholic civilization unless concrete steps were taken to oppose it. After ordinary means (preaching organized by the bishops, followed by preaching by Papal legates, followed by political pressure on the Count of Toulouse, who was sympathetic to the heresy, followed by diocesan inquisitions) had failed, the only option left to Pope Innocent III was to organize a crusade, to root the heresy out of the land by force of arms. And so, four years into this holy endeavor, the crusade’s leader, Count Simon de Montfort, found himself woefully short of men, and facing a large army bent on stopping this crusade, for a variety of political ends. After the first march of the crusade, the towns of Beziers and Carcassonne, with their viscounty, were taken. The viscount, Trencavel, had refused to capitulate, and died in prison shortly after his cities were captured. He, however, was a vassal of King Peter (Pedro) II of Aragon, to the south, who was at that point Christendom’s “shining star,” and had won great victories against the Moors in Spain. King Peter’s attempts at reconciliation between the crusade and his viscount, prior to the siege of Carcassonne, were ineffectual, and he had departed for his own lands, enraged at his rebuff and, at the time, impotent to do anything about it. Four years later, however, he was not so impotent, as he marched north with an army of 1,000 knights of (then as now anticlerical-minded) Barcelona, along with a good number of foot soldiers. His allies as yet unsubdued by the Crusade, the counts of Foix and Comminges, and the count of Toulouse himself, Raymond VI, supplied additional forces, so that the anti-crusade army consisted of around 4,000 cavalry, and 40,000 infantry Peter II, despite bearing the title “First Standard Bearer of the Church,” courtesy of the Pope, was determined to protect his influence in the area and keep the region’s ties to the king of France weak, while protecting his vassals. Raymond of Toulouse was also closely allied with King John of England, who controlled large portions of France at the time, and so opposition to the crusade, mounted predominantly by “French” knights, with support of the French king, seemed politically expedient. All Europe, from the Pope on down, was certain that the venture was at an end, and that the crusade would surely be annihilated. Against the massive Spanish and Tolousain army stood the army of the crusade, commanded by Simon de Montfort personally: he had heard Peter II’s march, and had hastened from the town of Fanjeaux with all the forces available to him to Muret, a key fortified town on the approach to Toulouse, which he could not afford to lose. If the town fell, the Languedoc populace already under his suzerainty would be inclined to give trouble, as only the current prestige of his name kept order, and the crusade would surely be finished. He had no choice but to take the field, as quickly as possible. On the way to Muret, he made a slight detour to the Cistercian abbey of Boulbonne. There, he laid his sword on the altar and prayed. When the sacristan of the abbey asked him in surprise and bewilderment, why, with his handful of men, he was attacking so famous a warrior as the Aragonese, King Peter (Pedro), Count Simon drew from his pouch an intercepted letter from King Peter to a mistress of his—the wife of a Languedocian baron—in which the King had written that it was for her sweet sake that he was fighting to drive out the French. “I do not fear this king,” said de Montfort, “who opposes the work of God for the sake of a harlot.” When he arrived in the town, which was already under loose siege, he brought with him an army of only 860 cavalry, and of those, less than 300 were actually knights. With him, too, came the clergy, who were directing the spiritual ends of the crusade, including no less than seven bishops, along with the future St. Dominic. St. Dominic formalized the current Dominican Rosary prior to the Battle of Muret. The Catholic forces were in the habit of praying the Rosary, at the suggestion of St. Dominic. The clergy resorted to the church, where the Counts of Comminges, Foix, and Toulouse were again formally excommunicated, along with “any others who might hinder the crusade.” Since legends assure us that the soldiers of the Count de Montfort said the Rosary on the eve of the Battle of Muret, which took place in 1213, one may infer that somehow and somewhere it had got its start by that time. Whatever else the Rosary has proved to be in succeeding centuries, it was the weapon par excellence for battling the principal dogmas of the Albigenses; to their unnatural hatred of life it opposed the story of Christ born of our flesh, living our life, dying for us. Perhaps the mysteries in use at that time (we have no assurance that they were the same as the fifteen we now use) were chosen to combat definite errors, or even varied to suit the season or the occasion. I here is evidence that this was done, and it fits so strongly into the personality of Dominic that it adds a formidable argument to the tradition. Dominic was holding the position of vicar to the Bishop of Carcassonne when his affairs and the course of the Albigensian Crusade were altered by the arrival of the King of Aragon with a large army. Peter of Aragon joined with the forces of the heretics and the Catholic armies were in perilous straits. It was decided to hold a council at Muret. Dominic made his way there and one of the few anecdotes we have concerning this period, occurred on this journey at the city of Castres. Here he had stopped to venerate the martyr St. Vincent and planned to lodge with the collegiate canons of Castres. When he did not appear for dinner, the prior sent one of the brothers to call him. The brother obeyed, but, on going into the church, he saw Dominic raised in the air in ecstasy before the altar. Not daring to disturb him, he returned and called the prior. So forceful was the impression of Dominic’s sanctity left on the prior’s mind, that shortly after this he joined him and was one of the first disciples of the Order. He was the celebrated Matthew of France. Dominic proceeded to Muret, and, on September 10th of the same year, the King of Aragon suddenly appeared before the walls of the city with an army of forty thousand men, the move took de Montfort by surprise; he was an able warrior and there is no other explanation for his being caught with such a small force. Hastily calling the bishop, he made an attempt to arrange a truce. Battle being inevitable, he prepared for death and determined to sell the city dearly. If the tradition is correct that the crusaders ascribed their victory to the assistance of Mary, whom they had invoked in the Rosary, we may well believe that it was at the suggestion of Dominic that they prayed. The defenders were only eight hundred; they could well afford to pray. As the Bishop gave the last blessing, de Montfort knelt before him, clad in armor, and made his vow: “I consecrate my blood and life for God and His Faith.” Meanwhile, King Peter, encamped outside the city of Muret, began a night of debauchery. Many of the barons of Languedoc, who were at that time completely in his power, had, it is said, put their wives and daughters at his disposition, and he debauched himself so strenuously (so his own son writes) that at Mass, the next morning, he could scarcely stand for the gospel. From his own perspective, he was assuredly master of the situation: he had a massive army, his opponents were now shut inside a city, with his army preventing a retreat, and could afford to indulge himself, while a leisurely siege was conducted. Such was the ordinary course of events in medieval warfare, when a smaller force found itself confronted by a much greater one. De Montfort, however, knew that such a path spelled disaster. He could not hope to outlast the king of Aragon, nor to defeat him in a siege, when he had only cavalry, whose advantages were wasted inside the confines of a medieval city. Every moment he delayed meant almost inevitable doom, and so he prepared a plan of attack. The clergy went into the church to pray, convinced that only a battle could now decide things, and the cause seemed hopeless. Mass had been said, the men had been confessed and given communion, and all had been blessed with a relic of the True Cross. With the last blessing of the Bishop of Toulouse, the men rode out to battle and the priests went into the church to pray. Whatever may he said against de Montfort regarding his politics or his intrigues, the battle of Muret proves that he was brave and resourceful in battle. De Montfort organized his men. He divided his force into three sections, each containing about a hundred knights and two hundred sergeants. These sergeants were cavalrymen, armed like knights, but not of noble blood. Into the first of the three sections, all the banners were concentrated, to draw the enemy’s attention. In the second were a number of knights who had sworn a personal oath to kill King Peter. The three groups filed out of a lesser-used gate, which was not heavily guarded in the early morning hours, taking especial care to be as silent as possible. His troops made a single charge; riding through the open gates, they first feigned a movement of retreat, then suddenly turned and dashed into the ranks of their opponents. The first two groups attacked frontally, wreaking havoc among the undisciplined and thoroughly surprised troops of the besieging army. They swept through the first body of Catalan knights without even having to kill one, so unorganized and unprepared for fight were they. Meeting no resistance, they plunged into the main body of the enemy, who by this point had formed ragged lines. The fighting became a confused affair, because the disciplined crusaders had been enjoined to keep together strongly as a unit, whereas the Spanish knights all wanted to “fight their own battle” and indulge in head-to-head duels. De Montfort’s third corps, meanwhile, had displaced the sentries in the rear after traversing a narrow path through a ravine, and attacked the left flank of the Aragonese. The violence of their attack carried them through the lines to the center of the opposing army where Peter of Aragon sat among his nobles. King Peter, upon hearing the advance of the first two squadrons, had been overcome by his own foolish pride, and instead of leading the army, exchanged armor with another knight so that he could fight on the front lines. The knight bearing the king’s armor, however, was less capable a fighter than the king, whose prowess on the field was legendary, and after being killed in a single blow, the crusaders knew they had been deceived. Peter, however, realizing the folly of his duplicity, was observing his army falling to pieces around him under the crusaders’ onslaught, and he attempted to rally his knights by crying “I am the king!” This however revealed his identity to the nearby knights of Simon De Montfort. Upon which, those knights who had sworn to take his life converged on his position, and he was at length overcome, along with every man of his household cavalry. A slaughter ensued. Demoralized, the army of the Aragonese attempted to flee, and hundreds were killed. The Toulousain infantry, however, had misunderstood the cavalry action, and believed that their chieftains had been victorious, whereupon they began to attack the walls of Muret. Bishop Fulk of Toulouse, knowing already by messenger of the victory, came out to reason with his flock, but they did not believe him, and continued the attack, until they were startled by the returning crusaders, panicked, and as many as 20,000 were slaughtered by the cavalry. Victory, improbable though it seemed, was theirs. Miraculously, only 1 knight, and perhaps 8 sergeants, were lost by de Montfort’s crusaders. Where was Dominic meanwhile and what place has this page of chivalry in the annals of his apostolic life? The flash of swords and the tramp of those galloping steeds startle us, so different is their mood from the story of his quiet lonely journeys over the mountains. Where are we to look for hint at Muret? Prejudiced writers are ready enough to tell us he was at the head of the crusaders carrying a crucifix and urging the men on to slaughter. The plain truth of the matter is, however, that nothing in his training could have fitted him to be the leader of a cavalry charge whose equal is scarcely to be found in history. The Battle of Muret does form part of the story of Dominic’s life; for a brief moment he was brought into contact with the stormy scenes of the crusade. But to find his place, we must leave the battlefield and go back to the church of Muret with the other priests and the women. They had sent their comrades as it seemed to certain death, and their prayer had in it the anguish of supplication. Prostrate on the pavement, they poured out their souls to God, beseeching Him to defend His servants who were exposed to death for His sake. We need scarcely be surprised that so wonderful a victory was looked upon as miraculous and counted as the fruit of prayer. De Montfort himself regarded it so. The battle of Muret was a desperate blow to the cause of Raymond. Very shortly after, Toulouse opened its gates to de Montfort. The battle of Muret was bloody, but it was decisive. Aragon was entirely removed as a factor in Languedoc, and the holy crusade was saved. Toulouse could never again openly challenge de Montfort on the battlefield, and through Our Lady’s intercession, was ultimately laid low and submitted to the king of France. Practical authority was therefore now in the hands of the servants of God, and the vile sect of the Albigensians was ultimately expunged from the land. The English Dominican historian, Nicholas Trivet wrote, “St. Dominic warred by prayer, De Montfort by arms. The first chapel in honor of the Rosary was built, out of gratitude, by Simon de Montfort in the town of Muret.” Muret remains to this day a very notable battle, not only in divine terms, as the first intercession by Our Lady by way of the Holy Rosary, but also in human terms, as one of the very few instances in which, between men of European stock, a small force has done the humanly impossible, defeating another many times its size. We may truly attribute this to divine revelation. Our Lady led us to victory in 1213, and in 1571—what victories will she not give us today, if we fervently beg her intercession, and resolve to pray her Rosary as devoutly and often as possible? |

PART FIVE : THE HOLY ROSARY FIGHTS ON THE SEAS!

|

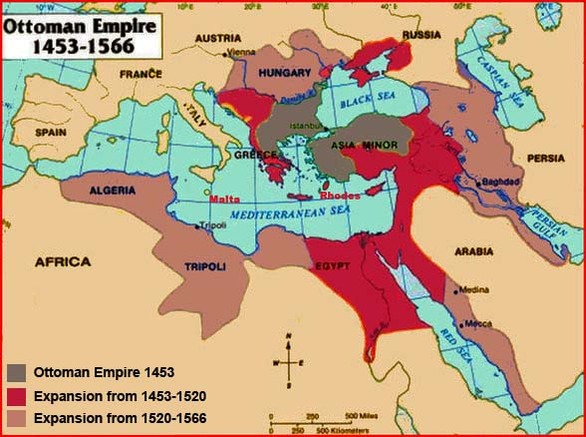

|

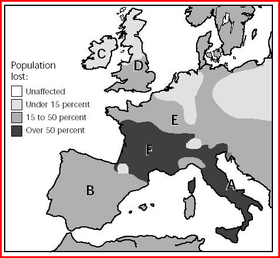

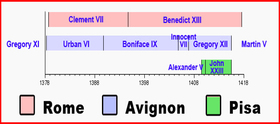

THE BATTLE OF LEPANTO (1571)

(for a full and thorough coverage of the Battle of Lepanto, follow our seven-part series, full of pictures, maps and battle simulation (click here for the Lepanto Homepage) From the Battle of Muret in 1213 to the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, we have a gap of 358 years. Was the Holy Rosary idle and dormant during that time? No, miracles of grace and physical/material miracles were still happening, but the Rosary did fall into decline in the intervening years—as did the Catholic Faith in general. THE BLACK DEATH was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, killing an estimated 75 to 200 million people and peaking in Europe in the years 1348–1350. The plague returned at intervals with varying virulence and mortality until the 18th century. The Black Death started in central Asia, and then traveled along the Silk Road, reaching Europe by 1346. Spreading throughout the Mediterranean and Europe, the Black Death is estimated to have killed 30–60% of Europe's total population. Half of Paris's population of 100,000 people died. In Italy, Florence's population was reduced from 110–120 thousand inhabitants in 1338, down to only 50 thousand in 1351. In Germany, at least 60% of Hamburg's and Bremen's population perished. Before 1350, there were about 170,000 settlements in Germany, and this was reduced by nearly 40,000 by 1450. The aftermath of the plague created a series of religious, social, and economic upheavals, which had profound effects on the course of European history. It took 150 years (up to the start of the 1500’s) for Europe's population to recover—the Battle of Lepanto would take place in 1571. THE AVIGNON PAPACY was the period from 1309 to 1378, during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon, in France, rather than in Rome. This situation arose from the conflict between the Papacy and the French crown. This absence from Rome is sometimes referred to as the “Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy”. A total of seven popes reigned at Avignon; all were French, and they increasingly fell under the influence of the French Crown. Finally, on September 13th, 1376, Gregory XI abandoned Avignon and moved his court to Rome. However, this split within the Catholic Church was not without effect—much like a patient who comes out of a severe disease and is debilitated for a long time afterwards. This weakness of the Church and Christendom was a source of profit to ever expanding Muslim Ottoman Empire. THE RENAISSANCE began in Florence, Italy, in the 1300’s, after the ravages of the Black Death. "When the cat's away, the mice will play" goes the saying. Well, here the papacy was away from Italy and under the influence of France (Avignon Papacy, see above), and so there was more freedom for the 'liberals' of the age to play around, which is exactly what many did. The Renaissance (meaning "rebirth") was a cultural movement that spanned the period roughly from the 14th to the 17th century (1300's to 1600's—the Battle of Lepanto was 1571), beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. Small republics came into existence in many places. They were full of activity, rich, original, boisterous. We need only mention Florence, Venice, Siena, Pisa and Genoa. These were flourishing cities, full of exuberant life. The turbulence of the Middle Ages did not die out with the progress of wealth and culture. On the contrary it grew more impassioned and expressed itself in fierce rivalry between the different parties, relentless struggles, savage vendettas and disordered ambitions—hence further weakening the Church and Christendom. There arose powerful tyrants, the product of audacity, pride and wealth. Humanism Side by side with this political evolution, a literary and intellectual movement, influenced by the political movement and often imitating its methods, also developed. It soon acquired the name of HUMANISM and it became one of the essential elements of the Renaissance. In fact from the very beginning an alliance was concluded between the powerful of the political world and the new intellectuals. The "tyrants" became the patrons of the men of letters and the artists who would flatter them and give them the glory they craved through their writing and their art. The humanists were very willing to collaborate in this way. They needed money and patrons. Humanism, as we shall shortly define it, became a lucrative and honored career. The Renaissance was a cultural movement that profoundly affected European intellectual life, and ended up profoundly affecting European moral life. It was the "rebirth" of paganism, for it threw aside many Christian principles and led to immorality on a grand scale. What was meant to be a cultural perfecting of man, ended up being a moral degeneration of man (but hidden under elegant trappings). To the point of not only King Henry VIII going through an unprecedented six wives (unlawfully married), but it also shook the Church, where there were several popes and many cardinals and bishops who kept mistresses and fathered children by them, and then appointed some of those children to posts as bishops and cardinals for material gain. Hence, further weakening the Church and Christendom. When that example comes from both Popes and Kings, then the filtering down to the grass-roots level is very easily done and very easily accepted. The whole focus of many of the highly-placed churchmen, kings and nobles, was to grow rich and powerful in worldly wealth and to show off that wealth as magnificently as possible, rather than growing in true wealth, which is the grace of God. The Medici Influence The Medici family story is truly fascinating and magnificent from a worldly viewpoint, yet tragic from a spiritual and supernatural viewpoint. Major increases in trade brought into play the existence of local and international banking. The Medici family became a family of bankers, and soon were the rulers of Florence, and through their patronage brought about the Renaissance and changed the western world forever. The Medici family was connected to most other elite families of the time, through marriages of convenience, partnerships, or employment, as a result of which the Medici family had a position of centrality in the social network. Members of the family rose to some prominence in the early 1300’s in the wool trade, especially with France and Spain. The Medici family increased the wealth of the family through his creation of the Medici Bank, and became one of the richest men in the city of Florence. “Lorenzo the Magnificent” was also an addict of humanism and brought many great artists and thinkers to Florence.One was Sandro Botticelli, another was to be Michelangelo. It was Botticelli who created the first overtly pagan and nude images at a time when the Church of the Middle Ages was still large and in charge. This sort of lukewarm, lax and liberal attitude resulted in enormously free creativity in art, as well as in writing and in the sciences. All of it was 'happening' in Florence and the worldly world of churchmen and nobles were wildly in favor of it all. The focus on God was rapidly losing ground to a focus on man. Protestant Revolution and Wars of Religion Germany had to deal with Martin Luther's rebellion against Rome, which sparked-off a whole series of similar rebellions throughout Europe, which only served to divide Christendom even further. He was urged on and supported by the 'Renaissance Crowd' who were basically not Christians, but neo-pagans, among them nobles who were not very noble, but seeking merely to get what they could by way of power, wealth and influence. Germany was already divided, but Luther's revolt divided it even more. In the 1500's, in France, there was a succession of wars between Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots primarily), known as the French Wars of Religion, which raged throughout France right up and shortly after the Battle of Lepanto of 1571. There was almost constant civil and religious war in France. The then Catholic land of England, once known as the "Island of Saints" and also "The Dowry of Mary", found itself plunged into schism by the time of Lepanto. King Henry VIII wanted an annulment so that he could marry again. The pope refused to annul his marriage. Henry remarried anyway, without the annulment. The Pope threatened to excommunicate him. Henry responded by making himself the head of the Church in England. The Anglican schism soon turned into a vast confiscation of Church property. The monasteries were entered, pillaged and sold. When Henry VIII died in 1547, having had six wives, he was succeeded by his son, Edward VI, aged ten years old. At this point the country rapidly moved towards pure Calvinism. Edward died aged sixteen and was succeeded by Mary Tudor, Henry's daughter from his first legitimate marriage. She was therefore Catholic and had remained Catholic. She released the Catholic bishops from prison and imprisoned the Lutherans and Calvinists in prison instead. As queen, she restored England to Catholicism, but died after five years in 1558. Mary was succeeded by Elizabeth, a typical product of the Renaissance, for whom religion was a mere cog in the political wheel. She overturned all the actions taken by Mary for a return to Catholicism and made the final break with Rome. So as Lepanto would approach, the Pope would find himself without the three "Super Powers" of the day, who, for one reason or another, could not or would not help Christendom fight the threat of the ever invading Muslims. This is the briefest of overviews, much more could be written on the terrible state of Europe, at that time, from all angles: religious, political, moral, intellectual, financial and artistic. Pride, division and rebellion ruled the day, where in a true Christendom there would be humility, unity and obedience. This was the sad backdrop to affairs that obviously helped the Turkish conquest. Europe was too busy fighting among themselves, in one sphere or another, that they did not truly care about what the Turks were doing, unless they got too close for comfort. Europe Divided and Diseased G. K. Chesterton described the state of Europe in the middle of the sixteenth century as being “in one of its recurring periods of division and disease”. There is no better description of that period in history in so few words. Europe, at the time of the Battle of Lepanto in October of 1571, was both divided and diseased: divided by religious quarrels and an explosion of sects with creeds denying the authority of the established Christian Church, and diseased with both excessive worldliness still flowing from the Renaissance and an excessive and superstitious austerity growing in opposition to it, but which had lost its Christian balance. THE EXPANSION OF THE MUSLIM OTTOMAN EMPIRE In stark contrast to “diseased and divided” Europe, the Turkish Ottoman Empire was, to all outward appearances, remarkably strong and unified. In 1453, the Turks had taken Constantinople, effectively completing their conquest of the remains of the Christian Byzantine Empire. By the first part of the sixteenth century, under the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, they began pressuring Europe on the Mediterranean as well as on Europe’s eastern frontiers, having ransacked and subdued much of the Balkans, Hungary, and Wallachia (now Romania) and threatening Vienna in 1529.