| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CHOOSE THE MIRACLE YOU WISH TO READ ABOUT FROM THE LINKS BELOW

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

| MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

THE VICTORY OF THE HOLY ROSARY AT LEPANTO

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

PART THREE

THE CONFRONTATION APPROACHES

The Ottoman Empire Eyes Europe

THE CONFRONTATION APPROACHES

The Ottoman Empire Eyes Europe

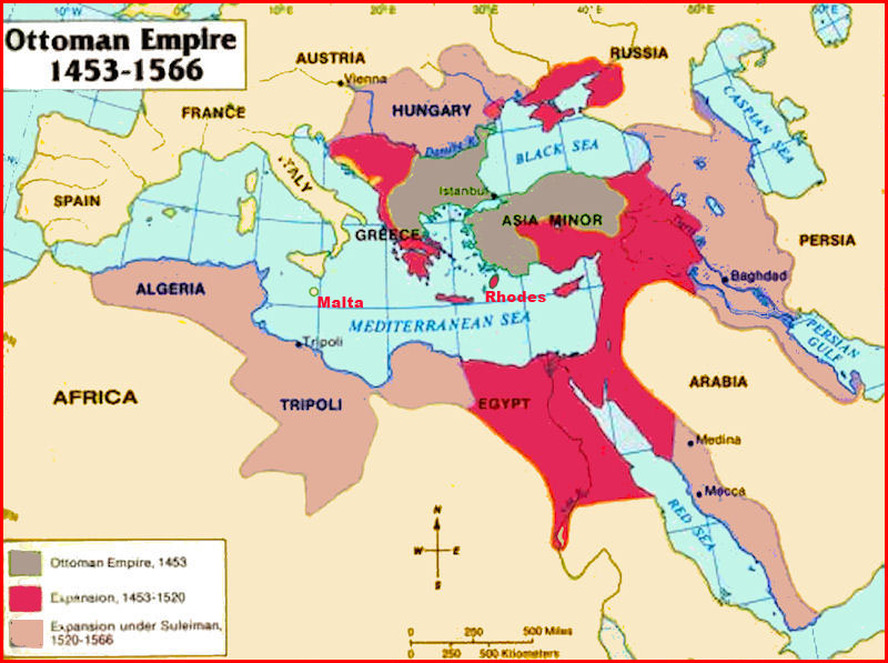

Ever since the tide turned in the Crusades, in favor of the forces of Islam, the Muslim Empire grew through the Middle East and spilled out into the surrounding areas of Europe, North Africa and Asia. The map below shows the growth of the Muslim Empire throughout the 15th and 16th centuries up to the period of the Battle of Lepanto.

|

The third part of these articles will show the showdown. For a long time, Christendom had been disintegrating and the Muslim Ottoman Empire was on the ascendancy, to the point that it by the time of Lepanto, it had total naval supremacy in the Mediterranean Sea. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Ottoman Empire was especially at the height of its power under the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566). The Ottoman Empire was a powerful multinational, multilingual empire controlling much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia, the Caucasus, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa. At the beginning of the 17th century the empire contained 32 provinces and numerous vassal states. Some of these were later absorbed into the empire, while others were granted various types of autonomy during the course of centuries.

G. K. Chesterton described the state of Europe in the middle of the sixteenth century as being “in one of its recurring periods of division and disease”. There is no better description of that period in history in so few words. Europe, at the time of the Battle of Lepanto in October of 1571, was both divided and diseased: divided by religious quarrels and an explosion of sects with creeds denying the authority of the established Christian Church, and diseased with both excessive worldliness still flowing from the Renaissance and an excessive and superstitious austerity growing in opposition to it, but which had lost its Christian balance. Infected Italy Italy was perhaps the most “worldly” of the nations in Christendom at the time; where the Renaissance had first sprung its vibrant flowers, the effects were lingering longest. In the various Italian states, Machiavellian politics were the order of the day, and the leading figures in much of Italian society were preoccupied with the preservation and expansion of their commercial interests. Venice was perhaps the most striking example of this, since it was a large city, situated in an area unsuitable for agriculture, supported almost entirely by international trade on the Mediterranean Sea. However, the Papal States and the Vatican itself were also not immune to the culture surrounding them. In many ways the popes since the Renaissance had actually helped to foster the sensual opulence and secretive politics that surrounded them. France’s Ferocious Faith Fighting France, perhaps more than any other European nation at the time, was in the midst of a violent internal religious conflict that had been fought on and off for almost a decade. Religion was not the only issue on which battles were being waged; many of the aristocracy, as well as the commercial interests in cities and towns, saw an opportunity in the civil disturbances to check the power of the French monarchy, which had been steadily increasing since the Middle Ages. The government of the nation itself, nominally ruled by King Charles IX, was ruled de facto by Charles’ mother, Catherine de Medici, a daughter of the powerful Italian Medici family. Her attempts to diffuse the religious fighting within France by compromise were largely unsuccessful, and at the time that the Turks appeared most threatening to Europe on the Mediterranean, France was ill equipped to turn a unified front outward to meet any threat. Spain’s Self-Serving Stance The kingdom of Spain, which also included at this time parts of France, Italy, and Belgium, as well as the Netherlands, was ruled by Philip II, son of Emperor Charles V. Philip was a devoutly Catholic, but painfully suspicious ruler who was obsessed with personally managing every detail of his entire empire. Philip had inherited, arguably, the most powerful empire in Europe, but struggled to keep his geographically dispersed territories under a firm central authority greatly taxed his resources. Philip had also intensified the workings of the Spanish Inquisition, and much of his personal energy and his government’s revenue were expended merely maintaining the status quo throughout his reign. Spain was also troubled by a large Muslim population in the South, which remained even after the Moors had been defeated two generations earlier. In November of 1570—less than a year before the Battle of Lepanto—the Spanish had finally put down an almost two-year-long revolt of Muslim “Moriscoes” in Granada. Germany’s Greedy Grabbers In different ways, both England and Germany were preoccupied with internal developments. Elizabeth I, in England, was concerned with solidifying the newly formed Church of England and suppressing the shrinking, but persistent, pockets of resistance to the new political and religious order. Germany was growing accustomed to its own religious divisions and these took up all of Germany’s attention and energy. Although Charles V had soundly defeated a coalition of Protestant princes at Miihlberg, in 1546, the spread of their Protestant religious doctrines had continued throughout Germany, almost without slowing, and the Peace of Augsburg, in 1555, had even given official recognition to the Protestant states. The German princes, whether Catholic or Protestant, had settled into an uneasy truce, for the time being, and were occupied with dividing or defending the lands they had greedily and happily gained, following the confiscation of Church property. England’s Evasive Elizabeth The “cold queen of England”: the Protestant Elizabeth I of England (1533—1603), who is considered “cold” for a number of reasons. She was known for never revealing her feelings in public, and her apparent aloofness is why some thought she never married. But her calculating approach toward marriage was genuinely cold: she regarded marriage as a diplomatic practice. She would periodically entertain the possibility of marriage whenever it would seem beneficial (that is, to form an alliance), but never followed through with it. Chesterton has her ‘looking in the mirror’, to paint her as self-absorbed and uncaring about the fate of Christian Europe. Ironically, although she offered no help whatsoever to the Holy League, she did recognize the significance of the victory at Lepanto once the battle was won, and she ordered the Church of England, which she had by now established by law, to hold services of thanksgiving! Persevering Pope Pius V Pope Pius V (I 504-1572), a Dominican monk, who was very holy and spiritually minded (and who was eventually canonized), was elected to the papacy right on the heels of the Turkish assault on Malta, and the air of tension and dread of the Turkish fleet was palpable throughout the Mediterranean. He was stunningly different from his Renaissance predecessors, who all came from the aristocratic class and were some of the most notoriously corrupt popes in history, and under whom Christendom had reached its splintered state. There was the agony of the Protestant Revolution and its resulting division of Christendom and its loss of souls within Christian Europe, but the most immediate threat came from without: from the Muslim Turks. The Turkish threat was felt most immediately by Spain and Italy, and, much to the new Pope’s consternation, both countries were jealously guarding their own interests and seemed almost completely unwilling to cooperate with one another. The new Pope, Pius V, was making valiant efforts to form a league “for the destruction and ruin of the Turk.” Yet, the essential political obstacles were still there and were more important than anything religious! The two great Christian naval powers in the Mediterranean were Spain and Venice; but until now, the interests of Spain and Venice had never coincided. Indeed, they were greatly at odds with each other. Papal Pleading As the spring of 1571 approached, almost five years of pleading on the part of Pius V, for Europe to unite in opposition to the threat of the Turkish fleet, seemed to have been without any effect; King Philip of Spain had pledged only a few ships to the Pope’s cause (because it seems he was saving them and building up his fleet for the future grand Spanish Armada of 130 ships and 26,000 soldiers and sailors, that was to sail to conquer England in 1588), and the Republic of Venice (then Italy’s primary naval power) was stalling. Pope Pius V understood the tremendous importance of resisting the aggressive expansion of the Turks better than any of his contemporaries appear to have. He understood that the real battle being fought was spiritual; a clash of creeds was at hand, and the stakes were the very existence of the Christian West. Let’s Unite! In Rome that year [1570], in the month of June, negotiations for a Holy League had officially begun. The Pope was sure in his own mind that, unless the Holy League could be made effective by the spring of 1571, the present chance of repelling the ever-increasing Turkish aggression would be lost. Combining acts of financial generosity with words of passionate conviction, he labored all winter to bring Spain and Venice closer—or, at least, to prevent their flying apart. To place limits on the bickering between Venice and Spain, the Pope had done his best to involve other powers, not always with success. The Pope had even gone so far as to seek help—of course in vain—from Ivan the Terrible of Russia. THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE In stark contrast to “diseased and divided” Europe, the Turkish Ottoman Empire was, to all outward appearances, re-markably strong and unified. In 1453, the Turks had taken Constantinople, effectively completing their conquest of the remains of the Christian Byzantine Empire. By the first part of the sixteenth century, under the Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, they began pressuring Europe on the Mediterranean as well as on Europe’s eastern frontiers, having ransacked and subdued much of the Balkans, Hungary, and Wallachia (now Romania) and threatening Vienna in 1529. Suleiman I (ruled 1520-1566) Suleiman I known as “the Magnificent” (1494 –1566) was the tenth and longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1520 to his death in 1566. Suleiman became a prominent monarch of 16th-century Europe, presiding over the peak of the Ottoman Empire’s military, political and economic power. Suleiman personally led Ottoman armies in conquering the Christian strongholds of Belgrade, Rhodes, as well as most of Hungary, before his conquests were checked and pegged-back at the Siege of Vienna in 1529. Under his rule, the Ottoman fleet dominated the seas from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and through the Persian Gulf. Fear Throughout Europe The fall of Christendom’s major strongholds spread fear across Europe. As the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire to Constantinople was to note, “The capture of Belgrade was at the origin of the dramatic events which engulfed Hungary. It led to the death of King Louis, the capture of Buda, the occupation of Transylvania, the ruin of a flourishing kingdom and the fear of neighboring nations that they would suffer the same fate.” Suleiman’s Conquests in Europe Upon succeeding his father, Suleiman began a series of military conquests, eventually suppressing a revolt led by the Ottoman-appointed governor of Damascus in 1521. Suleiman soon made preparations for the conquest of Belgrade from the Kingdom of Hungary—something his great-grandfather Mehmed II had failed to achieve. Its capture was vital in removing the Hungarians who, following the defeats of the Serbs, Bulgarians and the Byzantines, remained the only formidable force who could block further Ottoman gains in Europe. Suleiman encircled Belgrade and began a series of heavy bombardments from an island in the Danube. Belgrade, with a garrison of only 700 men, and receiving no aid from Hungary, fell in August 1521. Suleiman’s Siege of Rhodes The road to Hungary and Austria lay open, but Suleiman turned his attention instead to the Eastern Mediterranean island of Rhodes, the home base of the Knights Hospitaller. In the summer of 1522, taking advantage of the large Navy he inherited from his father, Suleiman dispatched an armada of some 400 ships towards Rhodes, while personally leading an army of 100,000 men across Asia Minor, to a point opposite the island of Rhodes itself. Here, Suleiman built a large fortification, Marmaris Castle, that served as a base for the Ottoman Navy. Following a siege of five months, known as the Siege of Rhodes (1522), with brutal encounters, Rhodes capitulated and Suleiman allowed the Knights of Rhodes to depart. The Knights of Rhodes eventually formed a new base in Malta. |

Suleiman Attacks Hungary

As relations between Hungary and the Ottoman Empire deteriorated, Suleiman resumed his campaign in Eastern Europe and on August 29th, 1526, he defeated Louis II of Hungary (1506–26) at the Battle of Mohács. In its wake, Hungarian resistance collapsed and the Ottoman Empire became the pre-eminent power in Eastern Europe. Upon encountering the lifeless body of King Louis, Suleiman is said to have lamented: “I came indeed in arms against him; but it was not my wish that he should be thus cut off, before he scarcely tasted the sweets of life and royalty.” Suleiman Attacks Vienna in Austria In 1529, Suleiman once again marched through the valley of the Danube and regained control of Buda (Hungary) and in the following autumn laid siege to Vienna (Austria). This was to be the Ottoman Empire’s most ambitious expedition in its drive towards the West. With a reinforced garrison of 16,000 men, the Austrians inflicted upon Suleiman his first defeat, sowing the seeds of a bitter Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry, which lasted until the 20th century. A second attempt to conquer Vienna failed in 1532, with Ottoman forces delayed by the siege of Güns, failing to reach Vienna. In both cases, the Ottoman army was plagued by bad weather (forcing them to leave behind essential siege equipment) and was hobbled by overstretched supply lines. In 1541 the Habsburgs (Austria) once again engaged in conflict with the Ottomans, by attempting to lay siege to Buda (in Hungary). With their efforts repulsed, and more Habsburg fortresses captured by the Ottomans in two consecutive campaigns in 1541 and in 1544 as a result, Ferdinand (Habsburg-Austrian) and his brother Charles V (Spain) were forced to conclude a humiliating five-year treaty with Suleiman. Ferdinand renounced his claim to the Kingdom of Hungary and was forced to pay a fixed yearly sum to the Sultan for the Hungarian lands he continued to control. Of more symbolic importance, the treaty referred to Charles V not as ‘Emperor’, but in rather plainer terms as the ‘King of Spain’, leading Suleiman to consider himself the true ‘Caesar’. With his main European rivals subdued, Suleiman had assured the Ottoman Empire a powerful role in the political landscape of Europe for some years to come. Suleiman’s Further Expansion in the Mediterranean and North Africa The presence of the Spanish, in the Eastern Mediterranean, concerned Suleiman, who saw it as an early indication of Spain’s Charles V’s intention to rival Ottoman dominance in the region. Recognizing the need to reassert the navy’s preeminence in the Mediterranean, Suleiman appointed an exceptional naval commander in the form of Khair ad Din, known to Europeans as “Barbarossa”. Once appointed admiral-in-chief, Barbarossa was charged with rebuilding the Ottoman fleet, to such an extent that the Ottoman navy equaled in number those of all other Mediterranean countries put together. In 1535, Spain’s Charles V won an important victory against the Ottomans at Tunis, which, together with the war against Venice the following year, led Suleiman to accept proposals, from Francis I of France, to form an alliance against Charles V of Spain. In 1538, the Spanish fleet was defeated by Barbarossa, at the Battle of Preveza, securing the eastern Mediterranean for the Turks for 33 years, until the Turkish defeat at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. East of Morocco, huge territories in North Africa were annexed. The Barbary States of Tripolitania, Tunisia, and Algeria became autonomous provinces of the Ottoman Empire, serving as the leading edge of Suleiman’s conflict with Spain’s Charles V, whose attempt to drive out the Turks failed in 1541. The piracy, carried on thereafter by the Barbary pirates of North Africa, can be seen in the context of the wars against Spain. For a short period Ottoman expansion secured naval dominance in the Mediterranean. France Makes an Alliance with Suleiman In 1542, facing a common Habsburg enemy (Austria-Spain), Francis I (of France) sought to renew the Franco-Ottoman alliance. As a result, Suleiman dispatched 100 galleys, under Barbarossa, to assist the French in the western Mediterranean. Barbarossa pillaged the coast of Naples and Sicily, before reaching France, where Francis made Toulon the Ottoman admiral’s naval headquarters. The same campaign had seen Barbarossa attack and capture Nice in 1543. By 1544, a peace between Francis I of France and Charles V of Spain, had put a temporary end to the alliance between France and the Ottoman Empire. Another Dark Knight Approaches Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, when the Knights Hospitallers, driven out of the Ottoman conquered island of Rhodes, were re-established as the Knights of Malta in 1530, by their actions against the Muslim navy, quickly angered the Ottomans, who assembled another massive army, in order to dislodge the Knights from Malta. The Ottomans invaded in 1565, undertaking the Great Siege of Malta, which began on May 18th and lasted until September 8th (Our Lady’s birthday. At first it seemed that this would be a repeat of the Battle on Rhodes, which ended in defeat for the Knights Hospitallers, for here, with most of Malta’s cities destroyed and half the Knights killed in battle, a repeat defeat looked to be on the cards; but a relief force from Spain entered the battle, resulting in the loss of 30,000 Ottoman troops and the victory of the local Maltese citizenry. Asian Expansion As Suleiman stabilized his European frontiers, he now turned his attention to the ever present threat posed by Persia. In 1534, Suleiman made a push towards Persia. When in the following year Suleiman and Ibrahim made a grand entrance into Baghdad, its commander surrendered the city, thereby confirming Suleiman as the leader of the Islamic world. Campaigns in the Indian Ocean Ottoman ships had been sailing in the Indian Ocean since the year 1518. In the Indian Ocean, Suleiman led several naval campaigns against the Portuguese, in an attempt to remove them and re-establish Turkish trade with India. Aden in Yemen was captured by the Ottomans in 1538, in order to provide an Ottoman base for raids against Portuguese possessions on the western coast of modern Pakistan and India. They fortified the city with 100 pieces of artillery. From this base, they managed to take control of the whole country of Yemen. With its strong control of the Red Sea, Suleiman successfully managed to dispute control of the Indian trade routes to the Portuguese and maintained a significant level of trade with the Mughal Empire of South Asia throughout the 16th century. In 1564, Suleiman received an embassy from Aceh (modern Indonesia), requesting Ottoman support against the Portuguese. This conquest and colonization explains the large Muslim presence in the area to this very day. Hopefully, the reader realizes what lay at stake in the approaching Battle of Lepanto. Christianity then, as it seems to be the case now, was disintegrating due increasing cravings for materialism and pleasure, together with an ascendancy of politics over religion. While, on the other hand, the Muslim Ottoman Empire was on the ascendancy and had its eyes clearly set upon Europe (as well as other parts of the globe). Suleiman the Magnificent did much to promote and expand this worldwide domination. He was to die, providentially, shortly before the Battle of Lepanto took place. His successor had nowhere near the military interest and capabilities. SUCCESSOR OF SULEIMAN Selim II (ruled 1566-1574) After the death of Suleiman the Magnificent, Selim II ascended to the throne of Sultan in 1566. The Ottoman Empire over which Selim II came to rule, stretched all along the northern coast of Africa from modern Algeria to the Nile Delta, and included the Sinai Peninsula and the entire strip along the eastern Mediterranean coast, including what is now Israel, Lebanon, and Syria, as well as Turkey, Greece, and most of modern Romania, Hungary, and the Balkans. Selim, though not particularly ambitious by nature, was under pressure to further expand the reaches of his empire. Every Ottoman Sultan was expected to bring at least one foreign state under Islamic rule during his reign. Keeping the Tradition of Conquest Alive Selim II was intent on fulfilling his obligation to expand the empire’s territory, and much of Europe was trembling with fear. Since Selim’s predecessor Suleiman had begun his expansion into Eastern Europe in 1521, with the exception of the successful defense of Vienna in 1529, no major Turkish force had been defeated in living memory, and the Turks had a propensity for garish displays of power and cruelty in battle as well as on civilian populations after a victory. Europe gained a small confidence boost when, in a surprising defeat, Selim’s (prior to his succession of Suleiman) forces unsuccessfully attempted to take the island of Malta in 1565. Chafed by this failure, Selim landed a much larger force on the Venetian-controlled island of Cyprus in 1570, conquering the defenses at Nicosia and Famagusta and making a gory spectacle of the latter city’s Venetian governor, by flaying him alive. As the summer of 1571 progressed, the Turkish fleet began raiding Venetian islands in the Adriatic, and the signs were clear that an attack on Italy was imminent. Selim Laughs at Europe The Sultan laughs because Christendom is not united, England and France have no interest in opposing the Turks, and Venice is tied to the Turks by trade agreements. Patiently following his strategy of dividing Venice from Spain, Sokolli the Grand Vizier, who ran the military side of things for Selim while he partied-away, let the Venetians know privately that a separate peace might always be possible.... Venice, of course, was playing a double game. “Peace is better for you than war,” Sokolli reminded the Venetians paternally “You cannot cope with the Sultan, who will take from you not only Cyprus alone, but other dependencies. As for your Christian League, we know full well how little love the Christian princes bear you. If you would but hold by the Sultan’s robe, you might do what you want in Europe, and enjoy perpetual peace” (Beeching, The Galleys at Lepanto, 166, 169). “Ali, the Turkish admiral, was keeping up the pressure on Venice. In June [1571] he raided Crete. By attacking one Venetian island after another that summer, the Turks reasoned that they could compel Venice to disperse her galleys, some here, some there, so that the entire Holy League fleet would never arrive at Messina.... He had the armed force to land an expedition in Italy, if he chose, a well-supplied battle fleet and an impregnable anchorage [at Lepanto].... The threat was unmistakable. If not this year then next, not only Venice and Rome but the kingdom of Naples and the island of Sicily, Spain’s breadbasket, would all lie within striking distance of this immense Turkish fleet and its army” (Beeching, The Galleys at Lepanto, 587-89). “The taking of Famagusta [a port on the island of Cyprus] in 1571 had therefore been planned as a stunning public demonstration of Turkish might—a preliminary to all-out war on other Venetian possessions. By an ostentatious and per-haps unnecessary display of force, the Sultan was making it clear that he still held command of the sea ... Sultan Selim could land an army, within striking distance of Rome, only if he had command of the sea. This is exactly what his attack on Cyprus ... had put at issue” ( Jack Beeching, The Galleys at Lepanto 174, 181). A Pope to the Rescue! In this seemingly dire situation there seemed to be only one light that shone brightly in “diseased and divided” Europe, and that was Pope Pius V. Elected pope in 1566, Pius V seemed the culmination of a quiet but rapid reformation in the papacy that, starting with Pope Paul III, brought true religious fervor and leadership back to the very top of the Catholic Church. Gone was the Renaissance worldliness and concern with secular affairs; Pius V knew that the most important issues of his day were the threats of Protestant heresies dividing Europe and the threat of the Muslim Turks conquering it, and that the victory in these struggles would only be won by utter reliance on the power and mercy of God. |

Web Hosting by Just Host