| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Holy Ghost

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CHOOSE THE MIRACLE YOU WISH TO READ ABOUT FROM THE LINKS BELOW

| MIRACULOUS MEDAL MIRACLES | MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

| MIRACULOUS MEDAL MIRACLES | MIRACLES OF LOURDES | SOLAR MIRACLE AT FATIMA | THE MIRACLE OF LEPANTO |

THE VICTORY OF THE HOLY ROSARY AT LEPANTO

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

(click on the links below to go to each part of the series of articles)

| Introduction : Miracle of Lepanto | Part 1 : Where on Earth is Lepanto? | Part 2 : Trouble Brewing | Part 3 : The Confrontation Approaches |

| Part 4 : Ready for Battle | Part 5 : Ships–Soldiers–Weapons–Tactics | Part 6 : The Battle and Victory | Part 7 : Lessons to be Drawn from Lepanto |

A series of articles, throughout the month of October,

on the miraculous victory of the outnumbered Christian fleet at Lepanto, on October 7, 1571.

on the miraculous victory of the outnumbered Christian fleet at Lepanto, on October 7, 1571.

INTRODUCTION

SETTING THE SCENE FOR THE BATTLE

SETTING THE SCENE FOR THE BATTLE

|

|

|

Before embarking on our journey in the past, let us first of all paint the big picture. This is going to be an in-depth and colorful excursion into one of the most renowned Rosary miracles on record. We will first of all look at the location of Lepanto (today it is called Naupactus or Nafpaktos), which is in present day Greece. Then we will look at the two contestants, the Christian forces and the Muslim forces—briefly looking at their track record in battles at that time. This will lead us into the battle itself, between the Christian fleet and the Ottoman (Muslim) fleet. In a brief manner, we will look at the battle, its tactics and its ebb and flow, while also looking at the prayer support that was going on "back at home". Then we will recount the manner of victory, accorded by Our Lady, to the Christian fleet and its consequences. Most people only have a superficial knowledge of this great event in the Church's history, we hope to deepen that knowledge and, consequently, deepen the love and confidence we should have towards the one who ultimately brought about that victory—the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Victories!

PART ONE

Let us first of all situate Lepanto in relation to the USA. We will then draw closer and position Lepanto (called Naupactus or Nafpaktos today) within Europe, in present day Greece. Then we will descend down to a local regional level, before finally looking at the town of Lepanto itself. So the big picture first, and then a gradual descent into more and more detail. Enjoy the trip! (CLICK HERE TO READ PART ONE)

ABOVE: The Straits of Messina, as seen from the south-west tip of Italy, looking south-west across the Straits of Messina at the island of Sicily. The famous Etna volcano can be seen in the distance, covered with snow. The narrowest part of the Straits is only 2 miles wide. At the harbor of Messina, it is about 3 miles wide.

PART TWO

THE WIDESPREAD CORRUPTION OF BOTH CHURCH & STATE

THE WIDESPREAD CORRUPTION OF BOTH CHURCH & STATE

Christendom has been gradually weakened since the 1400's and both Church and State have been growing increasingly corrupt. Power, greed, lust and violence have made greater and greater inroads into both Church and State. The 'backbone' of Christendom has become weak and so the Muslim forces, under the sway of the Ottoman Empire, have gradually taken over parts of Christian Europe and have their eyes set on Rome. (CLICK HERE TO READ PART TWO)

PART THREE

THE MUSLIM TURKISH FLEET AWAITS AT LEPANTO

|

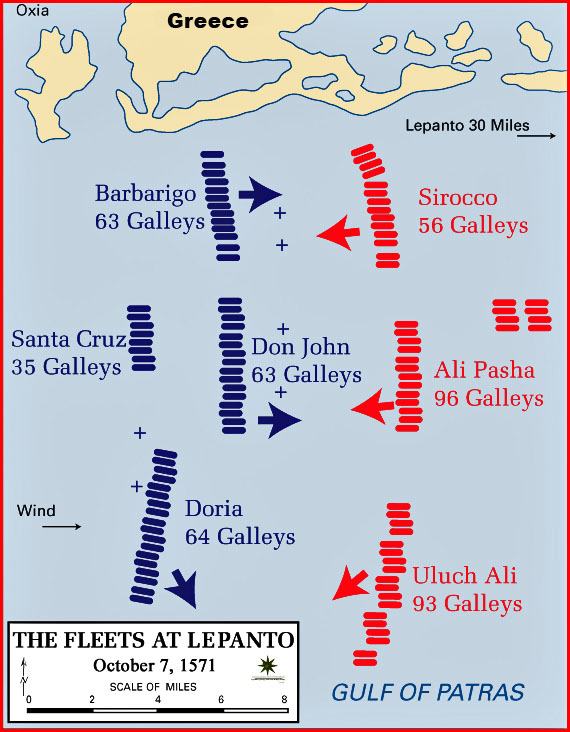

Anchored Safely in the Gulf

The Gulf of Lepanto is a long arm of the Ionian Sea running from east to west and separating the Pelloponnesian peninsula to the south from the Greek mainland to the north. Jutting headlands divide the Gulf into two portions: the inner one, called the Gulf of Corinth today, ends with the isthmus of the same name, and the outer one is an irregular, funnel-shaped inlet now called the Gulf of Patras. For six weeks Ali Pasha's ships had been anchored inside the fortified harbor of Lepanto located in the gulf's inner portion, and, on October 5th, they began to move slowly westward past the dividing headlands into the outer Gulf of Patras. Still unsure of the enemy's position, Ali Pasha ordered his fleet to drop anchor for the night in a sheltered bay fifteen miles from the entrance to the inlet, where it remained all the next day anxiously awaiting the return of the scouting vessels. The Alarm is Sounded Around midnight Kara Kosh reached the anchorage with the news that the Christian fleet was then at Cephalonia, an Ionian island almost directly opposite and parallel to the mouth of the Gulf of Lepanto. With the first light of dawn the following morning, October 7th, 1571, lookouts stationed high on a peak guarding the northern shore of the gulf's entrance signaled to Kara Kosh that the enemy was heading south along the coast and would soon round the headland into the gulf itself. |

Spiritual Battle Preparations

At sunrise on Sunday morning, October 7th, the chaplains on each ship were celebrating the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass as the vanguard of the fleet cruised south along the coast, turned the corner at the headlands, and entered the Gulf of Corinth. Since dawn the Turks had been moving in their direction from the east, with the advantage of having the wind at their back. While the ships of the League maneuvered from file to line abreast, Don John, with crucifix in hand, passed by each galley shouting encouragement and was met, as he made his way through the line, with tremendous applause and enthusiasm. By using tact and understanding, and forcefulness when necessary, he had welded many disparate elements into a united fleet. Although the Christian galleys were outnumbered, around 290 to 212 (these numbers vary greatly from one historian to another), they had superior firepower in cannon and arquebuses (primitive rifles), while the Turks relied mostly on bows and arrows. By nine o’clock the two lines were fifteen miles apart and closing fast. Wind Blows in Christian's Favor Just before contact was made, the wind that had been favoring the Turks shifted around from the east to the opposite direction. This was important for the six large galleasses, which were much larger, heavier and more sail reliant for their speed. Against the wind, they could barely move, other than by oars; but rowing such a large ship was slow-going, but with the wind in their sails, in addition to oars for more precise maneuverability, and being loaded with many cannons, they would suddenly became a lethal fighting force. The Ottoman Empire had grown so string that it now ruled the Mediterranean Sea, which made all Christian cities, ports and settlements close by the sea, a most vulnerable target. It was a case of 'now-or-never' for the Christians to act. However, there was a lot of bickering and jealousy among the Christian nations. In additions, there were civil wars going on in some Christian states between the Catholics and newly born groups of Protestants. Kings were reluctant to help the Pope fight-off the Turkish threat. The Pope knew that if something wasn't done now, then in a short time Christian Europe would be too weak to combat the Muslim invasion. (CLICK HERE TO READ PART THREE) |

PART FOUR

THE CHRISTIAN FLEET GATHERS TOGETHER IN SICILY

The Pope finally persuades some of the Christian States to assist him. He chooses a surprising leader for the Christian fleet and soldiers. The Pope had personally and successfully advocated to place leadership of the Holy League's fleet in the hands of Don John of Austria. Don John was half-brother to King Philip of Spain, but it was his own reputation for valor, honesty, and military skill that recommended him. Don John also understood the stakes at hand. As one historian comments: Don John knew "he had been given the task of fighting a total war against another system of ideas—historically the hardest of all wars to win" (The Galleys at Lepanto, Jack Beeching). Under his command, backed by the prayer of the Rosary, he sets sail for Lepanto. (CLICK HERE TO READ PART FOUR)

PART FIVE

SHIPS, SAILORS, SOLDIERS, WEAPONS & TACTICS

|

The Christian Fleet

As the Turks were planning further invasion of Europe, a coalition of Christian forces under John of Austria included 206 galleys and 6 galleasses. The Christian fleet consisted of 109 galleys and 6 galleasses from the Republic of Venice, 80 galleys from Spain, 12 Tuscan galleys of the order of St. Stephen, 3 galleys each from the Republic of Genoa, the Knights of Malta and the Duke of Suvoy, as well as some privately owned galleys. The fleet was manned by almost 13,000 sailors, 43,000 rowers and 28,000 soldiers, including 10,000 Spanish, 7,000 German, 6,000 Italian and 5,000 Venetian soldiers. Most of the 43,000 rowers were free oarsmen. The Turkish Fleet The Christian League was outnumbered by the larger Turkish fleet of 230 galleys and 60 galliots. Under the command of Ali Pasha, the 13,000 experienced sailors were drawn from all the maritime nations of the Ottoman Empire: Egyptians, Syrians, Greeks and Berbers. The Turkish fleet included 34,000 soldiers. |

Comparing the Opposing Forces

While the Christians were outnumbered in every other way, the Christian League had two significant advantages. Their infantry were definitely superior, and the Christians had 1,815 canons, compared to 750 among the Turkish vessels. The Christians also had more advanced muskets, while the Ottomans trusted in their greatly feared composite bowmen. Unlike the Christian fleet, the Turkish fleet was powered entirely by Christian slaves and prisoners of war forced to row in chains. According to naval practice in those days, the moment two rival fleets finally assumed their respective battle formations, the leader of one would fire a piece of artillery as a challenge to fight, and the opponent would answer by firing two cannon to signify that he was ready to give battle. This day it was the Turks who made the challenge, and the sharp report from Ali Pasha's flagship was quickly followed by double round from Don Juan's artillery. At this time a large green silk banner, decorated with the Muslim crescent and holy inscriptions in Arabic, was hoisted on the Turkish flagship. |

A look at the hardware of the battle: the ships, the soldiers, sailors, weapons and tactics of naval warfare in the 16th century! (CLICK HERE TO READ PART FIVE)

PART SIX

THE DAY OF THE BATTLE & THE DAY OF VICTORY

THE DAY OF THE BATTLE & THE DAY OF VICTORY

An account of the opening engagement and the battle that followed. A description of how things went from looking fatally grim to suddenly changing to victory for the Christian fleet. Read of the role that Our Lady of Guadalupe played in the battle! (CLICK HERE TO READ PART SIX)

|

|

PART SEVEN

What can we learn from Battle of Lepanto? What goes around also comes around. As they say, if we do not know and learn from our history, then we will have to learn by repeating it! We are on the threshold of history repeating itself. Are we taking the correct means to ensure the same miraculous victory? (CLICK HERE TO READ PART 7)

Web Hosting by Just Host