| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

WELCOME TO THE ANGER ROOM!

A Room for Curing Sinful Anger and Cultivating Virtuous Anger

The Articles will be left in their chronological order. Please scroll down for the latest article. If that makes you angry, then read on!

A Room for Curing Sinful Anger and Cultivating Virtuous Anger

The Articles will be left in their chronological order. Please scroll down for the latest article. If that makes you angry, then read on!

Article 1

The Angry Big Picture

The Angry Big Picture

|

A Birds-Eye View or Big Picture

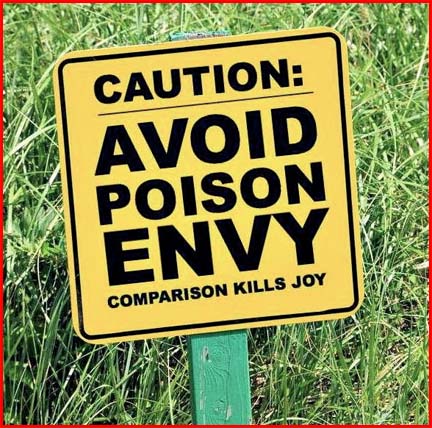

Anger is one of the Capital Sins: Pride, Covetousness, Gluttony, Anger, Lust, Envy and Sloth. Bishop Fulton Sheen calls them “the seven pall-bearers of the soul.” It is important to have discretion, or Christian prudence, to be able to discern clearly the virtue from sin in our words and actions, wherein it is easy to see virtue where there is sin, and to see sin where there is virtue. This is especially true in the case of anger—which can be both a virtue or a sin. Severity or excessive anger may be confused with justice; and a weakness in correcting and punishing, may be confused with mercy and prudence. Introducing the Sinful Family of Seven PRIDE comes first, because it is the grandaddy or gang-leader of them all. Pride, or its aliases of Vainglory and Vanity, introduces us to disobedience, boasting, hypocrisy, contention through rivalry, discord, love of novelties, and stubbornness. Pride strikes everyone, but in different ways. Anyone claiming to be free of pride is a liar. It is part and parcel of the Original Sin with which we were conceived and born into this world. COVETOUSNESS, or its aliases of Avarice or Greed, taking a lead from the gang-leader, Pride, will lead to a selfishness, a stinginess and draw us away from fraternal charity and almsgiving—because the focus in on self (me, my family, my job, my house, my things, my opinions, my invention, my talents, my…, my…, my…). If allowed to grow, it can become so feverish that it leads to lying, cheating, stealing, bitterness, anger and even murder in extreme cases. GLUTTONY and sensuality also produce other vices and may lead to blindness of spirit, to hardness of heart, to attachment to the present life even to the loss of hope of eternal life, and to love of self even to hatred of God, and to final impenitence. ANGER is also influenced by the gang-leader, Pride. Why do people get angry? Here we speak of sinful anger and not justified anger. I get angry because things are not going MY way! Because someone has offended ME! Because MY will is not being done! Because MY ambitions are not being achieved! These and many similar things are the causes and excuses for my anger. If only we would show a similar anger when those around us transgressed God! However, than ubiquitous specter of Human Respect steps in with the thought: “What will others think or say about this if I correct them?” Anger—when it is not justified indignation at wrongdoing, but a sinful anger by either excess or lack of foundation—is an inordinate movement of the soul which inclines us to repulse violently what displeases us. From anger arise quarrels, insults, and abusive words. We are very quick to show our Pharisaical anger when there is no Human Respect around―meaning we are amongst people who we are not afraid to vent our anger! So we criticize, demonize and verbally chastise those who are outside our circle—because they have no influence over us and cannot come back at us! How very fortunate! This kind of venting helps us preserve our image of being righteous people! It might be good for our image, but it is not good for our soul—as Judgment Day will show. LUST is the killer of the day, as Our Lady revealed at Fatima—and that was already back in ‘the good ole days’ of 1917!! How much worse has the world become in this regard over the last 100 years. We have descended a long way down the slippery slope since 1917—just look at the content on the screen, in magazines, in newspapers, in fashions! What would Our Lady’s opinion be today of the extent to which immodesty and impurity has descended? What would the folk of 1917 think of the way the way we dress in 2015? What we regard as decent, would be indecent to them. Lust is tinder wood or kindling wood—very easily set alight but then very difficult to put out! Once again: ”He that loveth danger shall perish in it” (Ecclesiasticus 3:27). Lust comes out of a lack of restraint or lack of temperance. The spiritual writers say that weakness of will and a neglect in mortifying our appetites with regard to eating and drinking, will transfer the weak will and neglect to the sexual appetite. Sloth also plays a part in the matter. Laziness in spiritual duties and exercises leads to a shortage of grace and weakness of will. ENVY, or willful displeasure at the sight of another’s good, as if it were an evil for us, similarly introduces us to hatred, slander, calumny, joy at the misfortune of another, and sadness at his success. SPIRITUAL SLOTH, or spiritual laziness, is a dislike or even a disgust for spiritual things and for the work of our sanctification, because of the effort it demands. It is a vice directly opposed to the love of God and to the holy joy that results from a love of God. Sloth or laziness introduces us to malice, rancor or bitterness toward our neighbor, fear or timidity in the face of duty to be accomplished, discouragement, spiritual lukewarmness, forgetfulness of the commandments and counsels of God, the seeking after forbidden things. Slipping downward on the slope of pride, vainglory, and spiritual sloth, many have lost their vocation. Lawful Anger Shown By God There is a lawful sentiment of anger, a righteous indignation, which is the ardent, but rational desire to visit upon the guilty a just retribution. Thus it was that Our Lord was roused to anger against the money‑changers whose traffic defiled His Father's house: “And the Pasch of the Jews was at hand, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. And He found in the Temple them that sold oxen and sheep and doves, and the changers of money sitting. And when He had made, as it were, a scourge of little cords, He drove them all out of the Temple, the sheep also and the oxen, and the money of the changers He poured out, and the tables He overthrew. And to them that sold doves He said: ‘Take these things hence, and make not the house of My Father a house of traffic!’” (John 2:13‑17). Whilst, on the other hand, Heli, the high‑priest, was severely reproved and punished by God for not having curbed the shameful conduct of his sons: “Now the sons of Heli were children of Belial, not knowing the Lord, nor the office of the priests to the people … Now Heli was very old, and he heard all that his sons did to all Israel: and how they lay with the women that waited at the door of the tabernacle. And he said to them: ‘Why do ye these kinds of things, which I hear, very wicked things, from all the people? Do not so, my sons: for it is no good report that I hear, that you make the people of the Lord to transgress!’ … And they hearkened not to the voice of their father … And there came a man of God to Heli, and said to him: ‘Thus saith the Lord: “Behold the days come: and I will cut off thy arm, and the arm of thy father’s house … And thou shalt see thy rival in the Temple, in all the prosperity of Israel … And this shall be a sign to thee, that shall come upon thy two sons, Ophni and Phinees: In one day they shall both of them die. And I will raise Me up a faithful priest, who shall do according to my heart, and my soul”’” (1 Kings 2:12; 22-24, 27-35). We see the anger of God in 40 year wanderings of the Chosen People in the desert—many were slain on various occasions by God because of their murmurings and infidelity. We see that same anger in the Babylonian Captivity and the destruction of the Ten Tribes of Israel. We see the same anger in the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple, together with the slaughter of over a million Jews by the Romans, which act of anger had been prophesied by Christ as a consequence of His being rejected by the Jews. The Anger of God Today “Who knoweth the power of thy anger?” (Psalm 89:11). Our Lady knows the anger of God very well—for she is always working hard to soften and mitigate it. She revealed this at both La Salette (France) and Akita (Japan): “If my people do not wish to submit themselves, I am forced to let go of the hand of my Son. It is so heavy and weighs me down so much, that I can no longer keep hold of it. I have suffered all of the time for all of you! If I do not wish my Son to abandon you, I must take it upon myself to pray for this continually. And all you think little of this. In vain you will pray, in vain you will act, you will never be able to make up for the trouble I have taken over for all of you” (La Salette) … “Many men in this world afflict the Lord. I desire souls to console Him to soften the anger of the Heavenly Father. I wish, with my Son, for souls who will repair by their suffering and their poverty for the sinners and the ungrateful. With my Son I have intervened so many times to appease the wrath of the Father. I have prevented the coming of calamities by offering Him the sufferings of the Son on the Cross, His Precious Blood, and beloved souls who console Him forming a cohort of victim souls. Prayer, penance and courageous sacrifices can soften the Father’s anger” (Akita). At La Salette and Akita Our Lady tried to communicate to us some of her incredible knowledge of the anger of God, in an attempt to make us take the anger of God very seriously: “In order that the world might know His anger, the Heavenly Father is preparing to inflict a great chastisement on all mankind … If men do not repent and better themselves, the Father will inflict a terrible punishment on all humanity. It will be a punishment greater than the deluge, such as one never seen before … If sins increase in number and gravity, there will be no longer pardon for them” (Akita) … “Woe to the inhabitants of the Earth! God will exhaust His wrath upon them, and no one will be able to escape so many afflictions together … Physical and moral agonies will be suffered. God will abandon mankind to itself and will send punishments which will follow one after the other … The society of men is on the eve of the most terrible scourges and of gravest events. Mankind must expect to be ruled with an iron rod and to drink from the chalice of the wrath of God” (La Salette). The Lawful Anger of Moses The anger of Moses mentioned in the Book of Exodus, was justified. “And Moses returned from the mount, carrying the two tables of the testimony in his hand … And when he came nigh to the camp, he saw the calf, and the dances: and being very angry, he threw the tables out of his hand, and broke them at the foot of the mount: and, laying hold of the calf which they had made, he burnt it, and beat it to powder, which he then threw into water, and gave thereof to the children of Israel to drink” (Exodus 32:15-20). An early writer, in keeping with the spirit of his time, brings home the viciousness of the Capital Sins by depicting them under the forms of animals. Pride is characterized as a lion; covetousness or avarice as a fox; lust as a scorpion; anger as a unicorn, ”which beareth on his nose the horn with which he butteth at all whom he reacheth”; envy as a venomous serpent; gluttony as ”the swine of greediness”; and sloth as a bear. Well, If God Can Be So Angry—Can I? The answer is both yes and no! We cannot just isolate God's anger from His other perfections—for example His patience and His mercy. To paint a picture of a "trigger-happy" God would be unjust and incorrect. Though, when He does pull that trigger, then everyone really feels that anger! |

Article 2

Am I Allowed to Be Angry?

Am I Allowed to Be Angry?

|

If God Can Be Angry, Can I?

Well, the answer is yes and no. It is true that God Himself has said: “Be angry and sin not” (Psalm 4:5). We would love to be able show anger as God shows anger—raining down fire and brimstone upon our enemies; causing earthquakes to swallow them up; flushing them all away with flood; having them wiped-out by a plague or pestilence; bringing a drought upon them! Wouldn’t that be fun? This is exactly what St. James and St. John—“the Sons of Thunder”—wanted in the time of Our Lord: “Jesus sent messengers before His face; and going, they entered into a city of the Samaritans, to prepare for Him. And they received Him not, because His face was of one going to Jerusalem. And when His disciples James and John had seen this, they said: ‘Lord, wilt Thou that we command fire to come down from Heaven, and consume them?’ And turning, He rebuked them, saying: ‘You know not of what spirit you are! The Son of man came not to destroy souls, but to save!’” (Luke 9:52-56). Don’t Be Rash! We see a little of that in the case of St. Paul—who went around seeking to arrest and imprison and even have put to death Christians—before his conversion on the road to Damascus: “Saul, as yet breathing out threatenings and slaughter against the disciples of the Lord” (Acts 9:1). Even after this “enemy of Christians” converted, many held him in suspicion, even Ananias himself, whom the Lord made instrumental in Saul’s conversion: “Ananias answered: ‘Lord, I have heard by many of this man, how much evil he hath done to Thy saints in Jerusalem! And here he hath authority from the chief priests to bind all that invoke Thy Name!’” (Acts 9:13-14). The Lord overturned Ananias’ protests with the shocking statement: “Go thy way; for this man is to Me a vessel of election, to carry My Name before the Gentiles, and kings, and the children of Israel. For I will show him how great things he must suffer for My Name’s sake!” (Acts 9:15-16). God Will Settle All Debts Saul—soon to be renamed Paul—did not get away “scot-free” with regard to his persecution of Christians. The persecutor, would by Divine Providence, become the persecuted. The Lord was not joking when He said: “I will show him how great things he must suffer for My Name’s sake!” St. Paul himself recounts a fraction of those sufferings: “They are the ministers of Christ―I am more: in many more labors, in prisons more frequently, in stripes above measure, in deaths often. Of the Jews five times did I receive forty stripes, save one. Thrice was I beaten with rods, once I was stoned, thrice I suffered shipwreck, a night and a day I was in the depth of the sea. In journeying often, in perils of waters, in perils of robbers, in perils from my own nation, in perils from the Gentiles, in perils in the city, in perils in the wilderness, in perils in the sea, in perils from false brethren. In labour and painfulness, in much watchings, in hunger and thirst, in fastings often, in cold and nakedness” (2 Corinthians 11:23-27). We Are “Trigger-Happy” We want instant vengeance upon our enemies! We want instant lightning and thunderbolts to crash down from Heaven and “take them out”. We are simply “trigger-happy” and not far-sighted enough! This brings to mind the words of Our Lord in the parable of the Cockle and the Wheat. Once the cockle was discovered growing among the wheat, the workers said to the master: “‘Sir, didst thou not sow good seed in thy field? Whence then hath it cockle? Wilt thou that we go and gather it up?’ And he said: ‘No, lest perhaps gathering up the cockle, you root up the wheat also together with it. Suffer both to grow until the harvest, and in the time of the harvest I will say to the reapers: Gather up first the cockle, and bind it into bundles to burn, but the wheat gather ye into my barn!’” (Matthew 13:27-30). Vengeance Belongs to God What else does this mean but that vengeance belongs to God: “For we know him that hath said: ‘Vengeance belongeth to Me and I will repay!’ And again: ‘The Lord shall judge His people!’” (Hebrews 10:30). “O Lord, thou wilt render to every man according to his works” (Psalm 61:13). “He that seeth into the heart, He understandeth, and nothing deceiveth the keeper of thy soul, and He shall render to a man according to his works!” (Proverbs 24:12). “For the Son of man shall come in the glory of His Father with His angels: and then will He render to every man according to his works!” (Matthew 16:27). |

Article 3

Think This Over Before You Explode Into A Tirade!

Think This Over Before You Explode Into A Tirade!

|

Listen to the Boss!

We do well to listen to the sage advice of the Holy Ghost, as He speaks to us through Holy Scripture—of which St. Paul says: “All Scripture, inspired of God, is profitable to teach, to reprove, to correct, to instruct in justice” (2 Timothy 3:1). Holy Scripture has much to say about anger, of which only a small part will be quoted here: ● “Let every man be slow to speak and slow to anger. For the anger of man worketh not the justice of God” (James 1:19-20). ● “He that is easily stirred up to wrath shall be more prone to sin” (Proverbs 29:22). ● “Envy and anger shorten a man's days” (Ecclesiasticus 30:26). ● “Let not the sun go down upon your anger” (Ephesians 4:26). ● “A mild answer breaketh wrath.” (Proverbs 15:1). ● “Let all bitterness and anger, and indignation and clamor, and blasphemy be put away from you, with all malice. And be ye kind one to another, merciful, forgiving one another, even as God hath forgiven you in Christ.” (Ephesians 4:31‑32). ● “Be not a friend to an angry man, and do not walk with a furious man” (Proverbs 22:24). ● “Anger resteth in the bosom of a fool” (Ecclesiastes 7:10). ● “But I say to you that whosoever is angry with his brother shall be in danger of the judgment. And whosoever shall say to his brother, 'Raca', shall be in danger of the council. And whosoever shall say, 'Thou fool', shall be in danger of Hell fire.” (Matthew 5:22). But I Am Justifiably Angry! We are always justified in our anger—aren’t we? There has never been a time when we have been unjustifiably angry—is there? Sadly, that is the case for most people. “The injustice of his own anger,” says St. Augustine, “is never apparent to an angry man.” God can well claim to be justifiably angry if anyone can—but look at how He approaches the matter. We love to show the momentous anger that God shows—Sodom & Gomorrha, the Great Flood, etc.—but just stop and think what led up to that anger! Patience Preceded God’s Anger God is most definitely not “trigger-happy” when it comes to anger—His patience invariably precedes His anger. He will show remarkable patience before unleashing a remarkable anger: “God is a just judge, strong and patient! Is He angry every day?” (Psalm 7:12). “The Lord delayeth not His promise [anger], as some imagine, but dealeth patiently for your sake, not willing that any should perish, but that all should return to penance” (2 Peter 3:9). “The Lord is patient and full of mercy, taking away iniquity and wickedness, and leaving no man clear, Who visitest the sins of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation” (Numbers 14:18). “Forasmuch as the Lord is patient, let us be penitent for this same thing, and with many tears let us beg His pardon” (Judith 8:14). Becoming Mild Cholerics St. Francis of Sales, on being asked how he could remain so imperturbably calm when faced with persons who were raging with anger, replied: “I have made an agreement, with my tongue, never to utter a word while my heart is excited.” How Francis developed a gentle and amiable disposition is a story in itself; he was not born a saint. By nature his temperament was choleric, fiery; little was needed to throw him into a state of violent anger. It took years before he mastered his impatience, his unruly temper. Even after he became bishop, there were slips, as for instance, when someone rang a bell before he had finished preaching. The important point, of course, is that, by constant perseverance, he did, with time, attain perfect self-mastery. Wherein lies a lesson for us! The Temperaments and Anger We have all heard of the “Four Temperaments”, but do we really know much about them? Our temperament powerfully affects our temper—for better or for worse. Having a temper does not always mean earthquakes, lightning bolts, fire falling from the sky, intolerable volume, verbal bombs being dropped, etc. Anger can also be seething and scathing without the “loudness” and “explosiveness” that we usually associate with anger. The Temperaments in Brief It must be stressed and remembered that nobody is made up of just one temperament. It can even possible to have characteristics from all of them. Nevertheless, there is one temperament with its characteristics that dominates our personality. The mixes can be wide ranging, encompassing all the possible percentiles. For example: 65% choleric, 20% melancholic, 10% sanguine and 5% phlegmatic or any possible combinations. Furthermore, the temperament may be modified, improved or worsened by education, discipline, environment, example, etc. The best assessment of what temperament we naturally are, is an assessment that looks upon us in our youngest years. CHOLERICS People with this temperament tend to be egocentric and extroverted. They may be excitable, impulsive, and restless, with reserves of aggression, energy, and/or passion, and try to instill that in others. They tend to be task-oriented people and are focused on getting a job done efficiently; their motto is usually “do it now.” They can be ambitious, strong-willed and like to be in charge. They can show leadership, are good at planning, and are often practical and solution-oriented. They appreciate receiving respect and esteem for their work. MELANCHOLICS It has been said that the Melancholy personality is the “richest of all temperaments, but at the largest cost.” History would probably reveal this to be true. Melancholy personalities are people who have a deep love for others, while usually holding themselves in contempt. They tend to be deep-thinkers and feelers who often see the negative attributes of life, rather than the good and positive things. Melancholies are often very gifted people in areas of art, literature, music, healthcare, ministry and so forth. They long to make a significant and lasting difference in their world. Sadly, many melancholies are also victims of deep bouts of depression that come from great dissatisfaction, disappointment, hurtful words or events. In short, melancholies take life very seriously―too much so sometimes, and it often leaves them feeling blue, helpless or even hopeless. Melancholies usually have a high degree of perfectionistic tendencies…especially in regards to their own lives or performance. They are very “introspective” and hold themselves to a very high standard―one that can rarely be achieved. SANGUINES The sanguine temperament is traditionally associated with air. People with this temperament tend to be lively, sociable, carefree, talkative, and pleasure-seeking. They may be warm-hearted and optimistic. They can make new friends easily, be imaginative and artistic, and often have many ideas. They can be flighty and changeable; thus sanguine personalities may struggle with following tasks all the way through and be chronically late or forgetful. PHLEGMATICS People with this temperament may be inward and private, thoughtful, reasonable, calm, patient, caring, and tolerant. They tend to have a rich inner life, seek a quiet, peaceful atmosphere, and be content with themselves. They tend to be steadfast, consistent in their habits, and thus steady and faithful friends. People of this temperament may appear somewhat ponderous or clumsy. Their speech tends to be slow or appear hesitant. They barely express emotion at all. While the sanguine might whoop and cheer and jump for joy at the slightest provocation, phlegmatics are unlikely to express more than a smile or a frown. Their emotions happen mainly internally. The Temperament of Our Lord Being all-perfect, Our Lord would have had all the strengths or positives of all four temperaments, and none of the weaknesses or negatives of any temperament. We, too, are called to the same level. Whereas Our Lord was born that way, we have to struggle and pray to get that way. Many people mistakenly think that the faults of their temperament are excusable because "God made me that way!" God, or more realistically, Original Sin made you that way and the state in which you find yourself is not the end of the journey and the struggle, but merely the beginning of it. You come into this world as an imperfect being and you are meant to leave it as a perfect being. |

Article 4

Anger and the Four Temperaments

Anger and the Four Temperaments

|

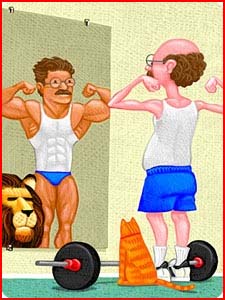

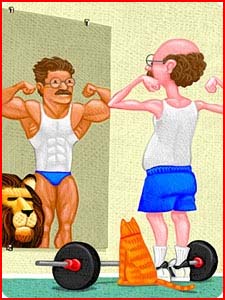

Know Thyself!

The famous Greek philosopher, Socrates, was often saying others: “Know thyself!” This also came to be a key element in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola, who would also insist: “Know thyself!” The so-called “Four Temperaments” are a magnificent means to knowing ourselves and others. So before we look at anger and temperaments in any kind of depth, we first of all need to understand what temperaments are all about! Hypocrites and Humor? The Four Temperaments, in their classic form, are hand-me-downs from the famous Greek, Hippocrates (pronounced hipo-cra-tease). He was no hypocrite, but a physician. Temperament theory has its roots in the ancient four humors theory (no joke, it’s true). It may have origins in ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia, but it was the Greek physician Hippocrates (460-370 BC) who developed it into a medical theory. He believed certain human moods, emotions and behaviors were caused by an excess or lack of body fluids, called "humors" (yeah, I know, a funny name!). These four humors are (1) blood, (2) yellow bile, (3) black bile, and (4) phlegm. Next, Galen (AD 129-200) developed the first typology of temperament in his dissertation De temperamentis, and searched for physiological reasons for different behaviors in humans. He classified them as hot/cold and dry/wet taken from the four elements. We’re a Pretty Mixed-Up Bunch! The word "temperament" itself comes from Latin “temperare”, meaning “to mix”. In the ideal personality, the complementary characteristics or warm-cool and dry-moist were exquisitely mixed and balanced. In four less ideal types, one of the four qualities was dominant over all the others. Is that all Greek to you? Never mind! Take it as a litmus test of your frustration and anger levels! Read on! Hippocrates’ work has been researched extensively and is used as a dynamic diagnostic tool in both psychology and psychiatry to this day. A generic explanation of human “Temperaments” or “Personalities” is that all of us have been born with genetically inherited “behavioral tendencies” that are as much a part of our DNA as is the color of our hair; all of us are made up of DNA combinations passed on to us through our parents and ancestors. This fact is important because it helps us to more fully understand our basic behavioral disposition. Even though much of our human personality is inherited, it should also be noted, much of it has also been influenced and shaped by our unique environments. Most scientific research on human behavior suggests that about 50% of the variations in human personality are determined by genetic factors — so our human behavior is shaped equally by our environment and by our DNA. Hard-Wired by God Thus, all of us as human beings have been hard-wired by our Creator ―we are not just products of random chance. “Thy hands have made me and formed me: give me understanding, and I will learn Thy commandments” (Psalm 118:73). “For Thou hast possessed my reins: Thou hast protected me from my mother’s womb. I will praise Thee, for Thou art fearfully magnified: wonderful are Thy works, and my soul knoweth right well. My bone is not hidden from Thee, which Thou hast made in secret: and my substance in the lower parts of the Earth. Thy eyes did see my imperfect being, and in Thy book all shall be written: days shall be formed, and no one in them” (Psalm 138:13-16). “Thus saith the Lord thy redeemer, and thy maker, from the womb: ‘I am the Lord, that make all things, that alone stretch out the Heavens, that establish the Earth, and there is none with Me!’” (Isaias 44:24). In addition to this, we must admit that we have all been impacted by the world around us. Divisions Furthermore, according to the scientific analysis, all human personalities are commonly divided up into four major categories of temperament, and these four types are further broken down into two categories — Extroverts and Introverts: „Extroverted Personalities: The Choleric and Sanguine personality-types are more “out-going,” more sociable, and more comfortable in a crowd, even standing out in a crowd. „Introverted Personalities: The Melancholy and Phlegmatic personality-types are more shy and “reserved” and feel anxious about being in crowd, especially at being singled-out in a crowd. A Bit of Everything It should be noted that all human beings have a degree of each of these four personality types within them, though each person will definitely test out higher in one, with another being a close second. No individual only possesses one personality type, and most of us have a very strong secondary temperament. Should you take one of the personality tests available today, you would discover that you possess dominant characteristics in a couple of the temperaments, and each kind of personality has a general characteristic associated with it. It should be noted that there are varying degrees of Extroversion and Introversion — in other words, some Phlegmatics and Melancholies “border” on being out-going, and some Cholerics and Sanguines “border” on being shy. Though the characteristics may not be true for everyone with a particular personality, they are generally true for the vast majority of people. Strengths and Weaknesses All four personality types have general strengths and weaknesses with which people must contend, and no one personality type is better than any other. All four have both good and bad qualities, and all four are needed to make this world a better place. Whatever your temperament or personality, God is the one who has given you the abilities and sensitivities that you possess, and He has given those things to you for a purpose — that you might faithfully work at developing them and using them in His service. Though our temperaments have been tainted by sin and the fall, God’s Spirit is mightily at work in us transforming us into the image of Christ that we might be more effective workmen in His Kingdom (John 17:17-20; 2 Corinthians 3:18; 5:20; Ephesians 4:7-16; Philippians 2:13). Remember, no two people are alike – we are all unique – and we have all been given a unique calling in life. Therefore it is important that we not covet qualities we do not possess; rather, that we focus on discovering God’s will for our lives and enjoy serving Him with the skill-set with which we have been blessed; knowing that God wants to use us to do the work for which He designed us. So identify your skills and strengths and get to work! Temperament and Marriage Of all the relationships we have in life, outside of God and Our Lady, marriage is by far the most important. A good relationship between a husband and a wife makes for a happy home. A marriage shadowed by bitterness, fighting and other unpleasantness, leaves its scars, on not only the couple, but also on their children and those around them. Good marriages are not just accidents — they are the result of hard work and understanding. In general, marriages between two people with the “same personality type” have the greatest potential for clashing, and anyone married to a sanguine or choleric is in for a challenge; this is mainly due to the tendencies of these two personality types to require excessive attention and control, respectively. Thus pretty much all marriages will have fairly significant challenges. Most often “opposites do attract” — Sanguine individuals tend to marry Melancholy ones, and Cholerics favor Phlegmatics; though such situations are not always the case, they do appear to be the most common. It should be noted that there is no such thing as “the ideal combination;” we are all fallen human beings with foibles and shortcomings. We can now look at each of the four temperaments or personalities and see how they manifest anger. This will be done in the next four articles. |

Article 5

Cholerics and Anger

Cholerics and Anger

|

|

I Wanna Be Top Dog

Cholerics are characterized by the element of Fire, the season of Summer, early adulthood, the color fiery red, Mars, and the characteristics of "Hot" and "Dry." The animal used to symbolize the Choleric is the lion. In our distant ancestors, the choleric members of the pack would be the alphas, the leaders. They would command their subordinates, and assert their dominance using force. If challenged, they would respond by getting angry, larger, in order to intimidate and to prove that they were the strongest, the most fit to lead. In current society, they often tend towards leadership roles, such as managers, politicians, captains, team leaders, and so on, though not necessarily. In fantasy, they might be the proud warriors, the esteemed Kings. The Choleric temperament is fundamentally ambitious and leader-like. The Choleric is the strongest of the extroverted Temperaments, and is sometimes referred to as a “Type A” personality or “the doer” (or “the driver”); he is a hard driving individual known for accomplishing goals—he has a lot of aggression, energy, and/or passion, and tries to instill it in others. Dominant in personality Cholerics desire control, and are best at jobs that demand strong control and authority, and require quick decisions and instant attention. Choleric people strive to be leaders and directors. They always seek to be in control of situations, to be on top, to be the best. This doesn't necessarily mean that they are all driven to reach the top of the corporate ladder on global scale, or that they all want to have leadership roles, but the tendency for being on top of everything is prevailing in day-to-day interactions with other people. They use imperative, commanding language, wording things as orders rather than requests. They are firm and forceful in their approach to problems. They believe in “tough love” and try to “help” others by challenging them to prove themselves, as they themselves would. Most bullies are Choleric, but few Cholerics are bullies. Many will in fact stand up to those who bully others, rather than letting them get away with things. Their confidence and demanding natures make them natural leaders, though this doesn't mean that they would necessarily enjoy leadership positions; they're just more likely to take charge if necessary rather than fumbling around worrying. They will “challenge” others aggressively in order to show their respect for the person's strength. They believe that it is important to “prove oneself”. They are driven by a desire to prove themselves greater than whoever they're arguing with, to assert that they are right, rather than to reach some kind of truth or compromise. They can lie in order to maintain the dominant position. The argument is about them more so than the issue; a battle of egos rather than a quest for truth. They love competition―but hate to lose. They are defiant of authority, challenging them as if to knock them off the top spot and assert their own dominance as the alpha of this pack, the leader of this tribe. They can be very condescending to those that they look down upon. They may take pleasure in the pain, misfortune, or humiliation of people they are not on good terms with. This is because it brings them pleasure to feel superior to others. They feel that they can define and understand and advise others, but laugh at the thought that others could do the same to them. This is because analyzing and defining another puts you in the superior position, while being defined would put them in the inferior position, which they resist. Extroverted Cholerics are extroverted in the sense that they will meddle in others' affairs and “speak their mind” if they feel it is necessary, rather than minding their own business. They generally respond well to new situations, and seek thrills. They must prove that they are strong. They speak their mind, but often don't mind their speech. Their pride and drive for dominance, as well as their open expression of emotion, naturally leads to outright aggression when challenged. They will raise their voices and get angry to show that they are the biggest and strongest, and to assert superiority. They are pragmatic, doing what needs to be done bluntly rather than worrying about fantasy scenarios. They will plough through obstacles that bar their path and they are single-minded in moving towards their goals. Main Strengths and Advantages In brief, people of choleric temperament possess multiple strengths: ● Natural leader ● Dynamic and active ● Compulsive need for change ● Must correct wrongs ● Strong-willed and decisive ● Unemotional ● Not easily discouraged ● Independent and self sufficient ● Exudes confidence Yet if these strengths are not subjugated to grace, then the Choleric can easily find his way to Hell. Some say that Cholerics will become either angels or devils. Choleric people are people of enthusiasm; they are not satisfied with the ordinary and crave for great success in all life affairs: large fortunes, a vast business, an elegant home, a distinguished reputation or a predominant position. The natural virtue of the choleric is ambition; his desire to excel and succeed despises the little and vulgar, and aspires to the noble and heroic. In their aspiration for great things Cholerics are supported by: 1. A keen intellect. The choleric person is not always, but usually endowed with considerable intelligence. 2. A strong will. The choleric person is not frightened by difficulties, but in case of obstacles shows his energy so much the more and perseveres also under great difficulties until he has reached his goal. 3. Strong passions. The choleric is very passionate. Whenever the choleric is bent upon carrying out his plans or finds opposition, he is filled with passionate excitement. 4. An often times subconscious impulse to dominate others and make them subservient. The choleric is made to rule. He feels happy when he is in a position to command, to draw others to him, and to organize large groups. Insensitive The Choleric is the most insensitive of the Temperaments; they care little for the feelings of others; feelings simply don’t play into the equation for them. Most Cholerics are men, and born leaders who exude confidence; they are naturally gifted businessmen, strong willed, independent, self-sufficient, they see the whole picture, organize well, insist on production, stimulate activity, thrive on opposition, are unemotional and not easily discouraged. They are decisive, must correct wrongs when they see them, and compulsively need to change things. They systematize everything, are all about independence, and do not do well in a subordinate position. They are goal oriented and have a wonderful focus as they work; they are good at math and engineering, are analytical, logical and pragmatic; and are masters at figuring things out. Suspicious and Skeptical They are skeptical and do not trust easy; they need to investigate the facts on their own, relying on their own logic and reasoning. If they are absorbed in something, do not even bother trying to get their attention. Negatively, they are bossy, domineering, impatient, can’t relax, quick tempered, easily angered, unsympathetic, enjoy arguments, too impetuous, and can dominate people of other temperaments, especially the Phlegmatic types. Many great charismatic military and political figures were Cholerics. They like to be in charge of everything—they are workaholics who thrive on control and want their way―they are highly independent people, and have very little respect for diplomas and other credentials. They set high standards, are diligent and hard-working, are rarely satisfied, and never give up their attempts to succeed. Choleric women are very rare, but strangely are very popular people. Anger Problem Cholerics have the most trouble with anger, intolerance and impatience; they want facts instead of emotions; and should you get your feelings hurt, it’s your problem, not theirs. The Choleric does not have many friends (though he/she needs them), and has a tendency to fall into deep sudden depression, and is much prone to mood swings. The Bible characters that seem to best fit the characteristics of a Choleric are the Apostles Paul and James, Martha and Titus. In addition to the characteristics listed below, the Choleric is essentially described as being organizational and an extrovert. Here is a brief overview of the tendencies of a Choleric: ● Is self-composed; seldom shows embarrassment, is forward or bold. ● Is eager to express him/herself before a group if he has some purpose in view. ● Is insistent upon the acceptance of his/her ideas or plans; argumentative and persuasive. ● Is impetuous & impulsive; plunges into situations where forethought would have deterred him/her. ● Is self-confident and self-reliant; tends to take success for granted. ● Exhibits strong initiative; tends to elation of spirit; seldom gloomy; prefers to lead. ● Is very sensitive and easily hurt; reacts strongly to praise or blame. ● Is not given to worry or anxiety; and is seclusive. ● Is quick and decisive in movement; pronounced or excessive energy output. ● Has marked tendency to persevere; does not abandon something readily regardless of success. ● Is characterized by emotions not freely or spontaneously expressed, except anger. ● Makes best appearance possible; perhaps conceited; may use hypocrisy, deceit, disguise. Special Things That Significant Others Can Do For The Choleric ● Do not force them to socialize. ● Do not interfere with their independence (provided that it is not sinful independence that seeks to withdraw from God and do sinful things). D not try to control them, or tell them what to do—this will anger them even more—didn’t anyone ever tell you? The Choleric is always right—or they think they are. If they are wrong, lead them to the acceptance of it by rational discussion and not a blunt, right on the nose, “You’re dead wrong!”. ● Recognize their need for accomplishments and give them opportunities to meet their need—provided that it does not fuel their sinful pride. ● Recognize their need to make decisions and take on responsibilities. Provide them the opportunity to do so. Others should not interfere with them when they are taking on tasks and responsibilities. Yet this is, of course, limited to moral limits and common sense. If they take a sinful course, then one does not make that easy for them, nor does one acquiesce and follow them blindly into it. ● Learn the art of negotiation to prevent being dominated by them. A blunt refusal is a red rag to a Choleric—they will feel obliged to steam-roller over your refusal. Logical discussion and reasoning is the key to a Choleric’s heart. ● Provide them with love and affection according to their needs and desires. ● Work hard at showing them they are loved by doing “special things” for them. But know that Cholerics do not like emotion and “softy” things. ● Render assistance when it is required. Though you may want to rub the Choleric’s nose in the fact that help is needed and that they cannot do it all themselves, refrain from doing so! This will be seen as an attack upon the Choleric’s staid and armored exterior. ● Keep emotional outburst to a minimum. What Cholerics Can Do For Themselves ● Deal with their anger constructively. Look at things supernaturally. Is the Providence of God behind the thing that is causing you anger. You may want things to go perfectly, but God may not! ● Find life situations where you can achieve things and receive recognition for the services you render. ● Find life situations where your need for accomplishments can be obtained. ● Recognize the rights and feelings of others. ● Submit to authority, especially that of God and His laws, while maintaining control of your own personal lives. ● Recognize the needs of others while showing love and affection, which is, not just giving love as a means of manipulation. ● Trust others and accept them as they are. ● Delegate responsibility in order to lessen the possibility of burnout. ● Refrain from using love and affection to control others. ● Only control others by good behavior, such as love, compassion, and encouragement, instead of abusive behavior. ● Learn how to forgive so you can release pent-up anger and painful memories that can fuel their vengeance. ● Learn to use the higher control of God’s grace that He has given you to control yourself, and not others. Behavioral Changes To Bring A Choleric Closer To God ● Forgive old painful memories and replace them with good, joyful ones. This will break the circle of anger and vengeance. ● Deal with anger constructively. Cholerics will lash out at others with an angry, cruel temper. They must never allow themselves to hurt people physically or emotionally when angry. ● Submit to God. They will rebel against God when they believe He is taking too much control of their life. This only breeds misery. Submission unlocks the potential for achievement God has placed within them. ● Recognize the rights and feelings of others according to the ordinances of God. They will walk over the rights and feelings of others to gain profit and power. ● Make their behavior pleasing to God. They have a tendency to undertake poor or sinful behaviors to maintain control of other people. ● Pray for the Fruit of the Holy Ghost – especially love, joy, peace, patience, goodness, faithfulness, kindness, gentleness, and self-control, so they can learn to understand and feel the emotions that are lacking in their temperament. They cannot understand or empathize with the deep, tender feelings of others. ● Dedicate all achievements to God and seek His recognition. This will lessen their dependence on man for recognition. Look at others with the “Eyes of Christ.” This will give them permission to be imperfect and lessen criticism. SUMMARY OF THE STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF A CHOLERIC

THE CHOLERIC AND ANGER

Now that we have a much clearer understanding of the Choleric temperament, we can proceed to examine the manner and the fields in which the Choleric can usually be tempted to and expected to manifest anger.

To distinguish between various kinds of anger—other than just and unjust anger—let us divide it into three categories: (1) Anger with self (2) Anger with others (3) Anger with God This corresponds to the three object of love in the commandment of Our Lord to love God with out whole heart and to love our neighbor as ourselves—thus God, neighbor and self. That is what we will now consider. Everybody has anger—it is just the extroverts (Choleric and Sanguine) who manifest it more obviously, but the introverts (Melancholic and Phlegmatic) also have anger to contend with, except that their anger is hidden from sight in most cases. Anger With Oneself There can be both a just and unjust anger with oneself, or to put it in other words, there can be a rational and irrational anger with self. We have all the right and reason in the world to be angry with ourselves with regard to sin. For sin is the greatest evil in the world—and if we committing the greatest evil in the world, then we should be angry. It is this that Holy Scripture has in mind, when it says: "Be angry, and sin not! The things you say in your hearts, be sorry for them upon your beds!” (Psalm 4:5). The Choleric is more ready to be angry with others than with themselves. They are more concerned with what goes on outside of themselves and around them, than they are concerned with what goes on inside themselves. They see them as leaders and better than most others. It is a little bit like the Pharisee in the Temple: “The Pharisee standing, prayed thus with himself: O God, I give thee thanks that I am not as the rest of men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, as also is this publican!” The Choleric (like other temperaments too) should pay attention to Our Lord’s words: “And why seest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye; and seest not the beam that is in thy own eye? Or how sayest thou to thy brother: Let me cast the mote out of thy eye; and behold a beam is in thy own eye? Thou hypocrite, cast out first the beam in thy own eye, and then shalt thou see to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye” (Matthew 7:3-5). The Choleric is extremely self-centered and also a perfectionistic--even the Choleric’s own flaws are flawless: they have a reason and excuse for all of their sins and failures. In their own minds, they are always right. Imperfections, sins or failures are not the Choleric’s fault, but somebody else’s fault, or the fault of nature or circumstances. When they are wrong they will not accept it, because theirs is the only way that is correct and matters. Thus they are rarely angry with themselves. They are gentle on themselves (usually) and hard on others. When it comes to making a fool of oneself, here the Choleric will be angry with himself or herself—what a stupid thing to do, to go and make a fool of oneself. With the Choleric wanting to be “top dog”, making a fool of oneself risks losing that position. If possible, some blame will be placed on others, or on circumstances. However, a Choleric, who is under the control and influence of divine grace, will be almost the reverse of the above. They will see more clearly their own faults and will use their super-string will to rectify and remedy those faults. With regard to others, they hold back whereas before they would attack. St. Francis de Sales was a big Choleric, but, by the grace of God, he had brought himself under control so much, that nobody even dreamed of him being a Choleric—until he himself revealed the fact, because his graciousness, mildness and humility were so great. So by praying to God and St. Francis de Sales, St. James and St. Paul—any Choleric could eventually find themselves in that same illustrious Choleric company. They say that a grace filled and grace guided Choleric, who has Melancholic traits as a secondary temperament, has the greatest likelihood of attaining to sanctity. Anger With Others |

Article 5

Sanguines and Anger

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

Sanguines and Anger

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

|

THE SUNNY TEMPERAMENT

The Sanguine temperament in social interaction, surface relationships and intellectual energies, is a very social person who likes to be with people. Of all the temperaments, the Sanguine is the easiest to be around socially. They are blessed with an innate happiness and optimism. They are an optimistic type of person who believes life is an exciting and fun-filled experience that should be lived to the fullest. Inactivity causes them stress because the pace at which they like to live their lives is fast and furious. They bring life and energy into a room by their very presence. Their cheerfulness and humor brighten everyone’s life. This can also have its dangers with regard to salvation—for though they are optimistic, they are also the most impulsive of all the temperaments. When the world offers fun and games, then for an undisciplined Sanguine, this can mean shipwreck. The following overview by Fr. Conrad Hock shows some of the key strengths and weaknesses of the Sanguine temperament. The sanguine temperament is fundamentally impulsive and pleasure-seeking; sanguine people are sociable and charismatic. They tend to enjoy social gatherings, making new friends and tend to be boisterous. They are usually quite creative and often daydream. However, some alone time is crucial for those of this temperament. Sanguine can also mean sensitive, compassionate and romantic. Sanguine personalities generally struggle with following tasks all the way through, are chronically late, and tend to be forgetful and sometimes a little sarcastic. Often, when they pursue a new hobby, they lose interest as soon as it ceases to be engaging or fun. They are very much people persons. They are talkative and not shy. Sanguines generally have an almost shameless nature, certain that what they are doing is right. They have no lack of confidence. Sanguines are associates with Air. Since the Sanguine temperament is basically the most equable and balanced of all, it's not surprising that the Sanguine facial types are also quite balanced, aesthetic and pleasing. The basic shape of the face and head is oval, or egg-shaped, with a tapering, delicate chin, mouth and lips. The eyes tend to be brown, limpid and almond shaped, quite beautiful in appearance; the rest of the facial features are pleasing and well-proportioned.. The hair is usually brown or chestnut colored, luxuriant and wavy. Dimples are common, and the neck tends to be long and elegant. The following is from The Four Temperaments, by Rev. Fr. -Conrad Hock: 1. THE SANGUINE IN BRIEF The Sanguine ... ● Is self-composed, seldom shows signs of embarrassment, perhaps forward or bold. ● Is eager to express himself before a group; likes to be heard. ● Prefers group activities; work or play; not easily satisfied with individual projects. ● Is not insistent upon acceptance of his ideas or plans; agrees readily with others’ wishes; compliant and yielding. ● Is good in details; prefers activities requiring pep and energy. ● Is impetuous and impulsive; his decisions are often (usually) wrong. ● Is keenly alive to environment, physical and social; likes curiosity. ● Tends to take success for granted. Is a follower; lacks initiative. ● Is hearty and cordial, even to strangers; forms acquaintanceship easily. ● Tends to elation of spirit; not given to worry and anxiety; is carefree. ● Seeks wide and broad range of friendships; is not selective; not exclusive in games. ● Is quick and decisive in movements; pronounced or excessive energy output. ● Turns from one activity to another in rapid succession; little perseverance. ● Makes adjustments easily; welcomes changes; makes the best appearance possible. ● Is frank, talkable, sociable, emotions readily expressed; does not stand on ceremony. ● Has frequent fluctuations of mood; tends to frequent alterations of elation and depression. The Sanguine person is quickly aroused and vehemently excited by whatever influences him. The reaction follows immediately, but the impression lasts but a short time. Consequently the remembrance of the impression does not easily cause new excitement. 2. FUNDAMENTAL DISPOSITIONS OF SANGUINES 1. Superficiality. The Sanguine person does not penetrate the depth, the essence of things; he does not embrace the whole, but is satisfied with the superficial and with a part of the whole. Before he has mastered one subject, his interest relaxes because new impressions have already captured his attention. He loves light work which attracts attention, where there is no need of deep thought, or great effort. To be sure, it is hard to convince a Sanguine person that he is superficial; on the contrary, he imagines that he has grasped the subject wholly and perfectly. 2. Instability. Because the impressions made upon a Sanguine person do not last, they are easily followed by others. The consequence is a great instability which must be taken into account by anyone who deals with such persons, if he does not wish to be disappointed. ● St. Peter, a Sanguine too, assured our Lord that he was ready to go with Him, even die for Him, only to deny a few hours later that he did not know "this man." ● The crowds hailed our Lord with their Hosannas on Palm Sunday but cried: “Crucify Him!” a few days later. The Sanguine is always changing in his moods; he can quickly pass from tears to laughter and vice versa; he is fickle in his views; today he may defend what he vehemently opposed a week ago; he is unstable in his resolutions. If a new point of view presents itself he may readily upset the plans which he has made previously. This inconsistency often causes people to think that the Sanguine person has no character; that he is not guided by principles. The Sanguine naturally denies such charges, because he always finds a reason for his changes. He forgets that it is necessary to consider everything, not superficially, but well; and to look into and investigate everything carefully beforehand, in order not to be captivated by every new idea or mood. He is also inconsistent at his work or entertainment; he loves variety in everything; he resembles a bee which flies from flower to flower; or the child who soon tires of the new toy. 3. Tendency to the external. The Sanguine does not like to enter into himself, but directs his attention to the external. In this respect he is the very opposite of the melancholic person who is given to introspection, who prefers to be absorbed by deep thoughts and more or less ignores the external. This leaning to the external is shown in the keen interest which the Sanguine pays to his own appearance, as well as to that of others; to a beautiful face, to fine and modern clothes, and to good manners. In the Sanguine the five senses are especially active, while the choleric uses rather his reason and will and the melancholic his feelings. The Sanguine sees everything, hears everything, talks about everything. He is noted for his facility and vivacity of speech, his inexhaustible variety of topics and flow of words which often make him disagreeable to others. The Sanguine person in consequence of his vivacity has an eye for details, an advantageous disposition which is more or less lacking in choleric and melancholic persons. 4. Optimism. The Sanguine looks at everything from the bright side. He is optimistic, overlooks difficulties, and is always sure of success. If he fails, he does not worry about it too long but consoles himself easily. His vivacity explains his inclination to poke fun at others, to tease them and to play tricks on them. He takes it for granted. that others are willing to take such things in good humor and he is very much surprised if they are vexed on account of his mockery or improper jokes. 5. Absence of deep passions. The passions of the Sanguine are quickly excited, but they do not make a deep and lasting impression; they may be compared to a straw fire which flares up suddenly, but just as quickly dies down, while the passions of a choleric are to be compared to a raging, all-devouring conflagration. This lack of deep passions is of great advantage to the Sanguine in spiritual life, insofar as he is usually spared great interior trials and can serve God as a rule with comparative joy and ease. He seems to remain free of the violent passions of the choleric and the pusillanimity and anxiety of the melancholic. 3. DARK SIDE OF THE SANGUINE TEMPERAMENT 1. Vanity and self-complacency. The pride of the Sanguine person does not manifest itself as inordinate ambition or obstinacy, as it does in the choleric, nor as fear of humiliation, as in the melancholic, but as a strong inclination to vanity and self-complacency. The Sanguine person finds a well-nigh childish joy and satisfaction in his outward appearance, in his clothes and work. He loves to behold himself in the mirror. He feels happy when praised and is therefore very susceptible to flattery. By praise and flattery a Sanguine person can easily be seduced to perform the most imprudent acts and even shameful sins. 2. Inclination to flirtation, jealousy and envy. The Sanguine person is inclined to inordinate intimacy and flirtation, because he lacks deep spirituality and leans to the external and is willing to accept flatteries. However, his love is not deep and changes easily. An otherwise well-trained Sanguine would be content with superficial familiarities as tokens of affection, but in consequence of his levity and readiness to yield, as well as on account of his optimistic belief that sin may have no evil consequences, he can be easily led to the most grievous aberrations. A bad woman with a Sanguine temperament yields herself to sin without restraint and stifles the voice of conscience easily. Vanity and tendency to love-affairs lead the Sanguine person to jealousy, envy, and to all the petty, mean, and detestable faults against charity, which are usually the consequence of envy. Because he is easily influenced by exterior impressions or feelings of sympathy or antipathy, it is hard for the Sanguine person to be impartial and just. Superiors of this temperament often have favorites whom they prefer to others. The Sanguine is greatly inclined to flatter those whom he loves. 3. Cheerfulness and inordinate love of pleasure. The Sanguine person does not like to be alone; he loves company and amusement; he wants to enjoy life. In his amusements such a person can be very frivolous. 4. Dread of virtues which require strenuous efforts. Everything which requires the denial of the gratification of the senses is very hard on the Sanguine; for instance, to guard the eyes, the ears, the tongue, to keep silence. He does not like to mortify himself by denying himself some favorite food. He is afraid of corporal acts of penance; only the exceptionally virtuous Sanguine succeeds in performing works of penance for many years for sins committed in earlier youth. The ordinary Sanguine person is inclined to think that with absolution in the sacrament of penance all sins are blotted out and that continued sorrow for them is unnecessary and even injurious. 5. Other disadvantages of the Sanguine temperament: (a) The decisions of the Sanguine person are likely to be wrong, because his inquiry into things is only superficial and partial; also because he does not see difficulties; and finally because, through feelings of sympathy or antipathy he is inclined to partiality. (b) The undertakings of the Sanguine fail easily because he always takes success for granted, as a matter of course, and therefore does not give sufficient attention to possible obstacles, because he lacks perseverance, and his interest in things fades quickly. (c) The Sanguine is unstable in the pursuit of the good. He permits others to lead him and is therefore easily led astray, if he falls into the hands of unscrupulous persons. His enthusiasm is quickly aroused for the good, but it also vanishes quickly. With Peter he readily jumps out of the boat in order to walk on the water, but immediately he is afraid that he may drown. He hastily draws the sword with Peter to defend Jesus, but takes to flight a few minutes later. With Peter he defies the enemies of Jesus, only to deny Him in a short time. (d) Self-knowledge of the Sanguine person is deficient because he always caters to the external and is loath to enter into himself, and to give deeper thought to his own actions. (e) The life of prayer of the Sanguine suffers from three obstacles: He finds great difficulty in the so called interior prayer for which a quiet, prolonged reflection is necessary; likewise in meditation, spiritual reading, and examination of conscience. He is easily distracted on account of his ever active senses and his uncontrolled imagination and is thereby prevented from attaining a deep and lasting recollection in God. At prayer a Sanguine lays too much stress upon emotion and sensible consolation, and in consequence becomes easily disgusted during spiritual aridity. 4. BRIGHT SIDES OF THE SANGUINE TEMPERAMENT 1. The Sanguine person has many qualities on account of which he fares well with his fellow men and endears himself to them. (a) The Sanguine is an extrovert; he readily makes acquaintance with other people, is very communicative, loquacious, and associates easily with strangers. (b) He is friendly in speech and behavior and can pleasantly entertain his fellow men by his interesting narratives and witticisms. (c) He is very pleasant and willing to oblige. He dispenses his acts of kindness not so coldly as a choleric, not so warmly and touchingly as the melancholic, but at least in such a jovial and pleasant way that they are graciously received. (d) He is compassionate whenever a mishap befalls his neighbor and is always ready to cheer him by a friendly remark. (e) He has a remarkable faculty of drawing the attention of his fellow men to their faults without causing immediate and great displeasure. He does not find it hard to correct others. If it is necessary to inform someone of bad news, it is well to assign a person of Sanguine temperament for this task. (f) A Sanguine is quickly excited by an offence and may show his anger violently and at times imprudently, but as soon as he has given vent to his wrath, he is again pleasant and bears no grudge. 2. The Sanguine person has many qualities by which he wins the affection of his superiors. (a) He is pliable and docile. The virtue of obedience, which is generally considered as difficult, is easy for him. (b) He is candid and can easily make known to his superiors his difficulties, the state of his spiritual life, and even disgraceful sins. (c) When punished he hardly ever shows resentment; he is not defiant and obstinate. It is easy for a superior to deal with Sanguine subjects, but let him be on his guard! Sanguine subjects are prone to flatter the superior and show a servile attitude; thus quite unintentionally endangering the peace of a community. Choleric and especially melancholic persons do not reveal themselves so easily, because of their greater reserve, and should not be scolded or slighted or neglected by the superiors. 3. The Sanguine is not obdurate in evil. He is not stable in doing good things, neither is he consistent in doing evil. Nobody is so easily seduced, but on the other hand, nobody is so easily converted as the Sanguine. 4. The Sanguine does not long over unpleasant happening Many things which cause a melancholic person a great, deal of anxiety and trouble do not affect the Sanguine in the least, because he is an optimist and as such overlooks difficulties and prefers to look at affairs from the sunny side. Even if the Sanguine is occasionally exasperated and sad, he soon finds his balance again. His sadness does not last long, but gives way quickly to happiness. This sunny quality of the well trained Sanguine person helps him to find community life, for instance, in institutions, seminaries, convents much easier, and to overcome the difficulties of such life more readily than do choleric or melancholic persons. Sanguine persons can get along well even with persons generally difficult to work with. 5. METHOD OF SELF-TRAINING FOR THE SANGUINE 1. A Sanguine person must give himself to reflection on spiritual as well as temporal affairs. It is especially necessary for him to cultivate those exercises of prayer in which meditation prevails; for instance, morning meditation, spiritual reading, general and particular examination of conscience, meditation on the mysteries of the rosary, and the presence of God. Superficiality is the misfortune, reflection the salvation of the Sanguine. In regard to temporal affairs, the Sanguine person must continually bear in mind that he cannot do too much thinking about them: he must consider every point; anticipate all possible difficulties; he must not be overconfident, over optimistic. This is the remedy for superficiality. 2. He must daily practice mortification of the senses, the eyes, ears, tongue, the sense of touch, and guard the palate against overindulging in exquisite foods and drinks. This is the remedy for sensuality. 3. He must absolutely see to it that he be influenced by the good and not by the bad; that he accept counsel and direction. A practical aid against distraction is a strictly regulated life, and in a community the faithful observance of the Rules. This is a remedy for naivety. 4. Prolonged spiritual aridity is a very salutary trial for him, because his unhealthy sentimentality is thereby cured or purified. 5. He must cultivate and deepen his good traits, such as charity, obedience, candor, cheerfulness, and sanctify these natural good qualities by supernatural motives. He must continually struggle against those faults to which he is so much inclined by his natural disposition, such as, vanity and self-complacency; love of particular friendships; sentimentality; sensuality; jealousy; levity; superficiality; instability. 6. POINTS OF IMPORTANCE IN DEALING WITH AND EDUCATING A SANGUINE PERSON The education of the Sanguine person is comparatively easy. He must be looked after; he must be told that he is not allowed to leave his work unfinished. His assertions, resolutions, and promises must not be taken too seriously; he must continually be checked as to whether he has really executed his work carefully. Flatteries must not be accepted from him and especially constant guard must be kept lest any preference or favoritism be shown him on account of his affable disposition. It must be remembered that the Sanguine person will not keep to himself what he is told, or what he notices about anyone. It is advisable to think twice before taking a Sanguine person into confidence. In the education of a Sanguine child the following points should be observed: 1. The child must be consistently taught to practice self-denial especially by subduing the senses. Perseverance at work and observance of order must be continually insisted upon. 2. The child must be kept under strict supervision and guidance; he must be carefully guarded against bad company, because he can so easily be seduced. 3. Leave to him his cheerfulness and let him have his fun, only guard him against overdoing it. (Here ends the extensive reference from Fr. Conrad Hock). SUMMARY OF THE STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF A SANGUINE

THE SANGUINE AND ANGER

Now that we have a much clearer understanding of the Sanguine temperament, we can proceed to examine the manner and the fields in which the Sanguine can usually be tempted to and expected to manifest anger.