| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

click on the page of your choice

| Why Souls Suffer in Purgatory | Saints Speak on Purgatory | Stories of Purgatory | History of All Souls Day |

| Read Me, Or Rue It | Unpublished Manuscript on Purgatory | Download Purgatory Posters |

| Why Souls Suffer in Purgatory | Saints Speak on Purgatory | Stories of Purgatory | History of All Souls Day |

| Read Me, Or Rue It | Unpublished Manuscript on Purgatory | Download Purgatory Posters |

Sister Lucia of Fatima on Purgatory

“I have been asked many questions concerning this reply of Our Lady and I don't know too well how to answer them. I didn't ask Our Lady for a clarification, I was too young to think about that. But I have meditated a lot about this detail of the Message.

“After all—I ask myself—what is Purgatory, actually? ... We see that the word "Purgatory" means "purification," and as all of us are more or less sinners, all of us need being purified of our own sins, faults, and imperfections, in order to be admitted to the enjoyment of the possession of the Kingdom of eternal glory.

"We can still realize this purification during this life, if God gives us the time for it: by asking God for forgiveness, with sincere repentance and the resolution to change our life by doing penance, receiving the sacrament of Confession.

[At this point, Sister Lucia sums up all kinds of sins and continues]:

“All these things, and many others, too numerous to mention, are against the commandments of the Law of God and require a great purification, even if they have already been confessed and forgiven with respect to their punishment . . . but not expiated with respect to their purification; until this [expiation] renders us worthy to be admitted to the immense ocean of God's Being.

“This purification—that is called "Purgatory"—can be more or less extended, depending on the number of our sins, faults, and imperfections, and on their gravity, for which we have not given complete satisfaction by means of reparation, good works, penance, and prayers.

“And how are we purified in Purgatory, or what purifies us? I don't know very well. In the past, they said that we are purified by being thrown in a hot fire, and that this fire was equal to that of Hell. Modern writers seem not to concord any more with this way of thinking.

“As for me, it seems to me that what purifies us is love, the fire of divine love, which is communicated by God to the souls in proportion as every soul corresponds. It is said that if a soul is granted the grace to die with a perfect act of love, that this love purifies it totally, so that it can go straight to Heaven. This shows us that what purifies is love, along with contrition, sorrow for having offended God and the neighbor, by sins, faults, and imperfections, because all this is against the first and last commandments of the Law of God: You shall love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole strength. That way, the small or big flame of love—even though it be only a wick that is still smoldering—will not extinguish, but will be scintillating and increasing, until it totally purifies the soul and makes it dignified to be admitted to live in the immense ocean of the Being of God, to participate with all the other blessed ones in the wisdom, power, knowledge, and love of God, in proportion as God wants to communicate it to every soul; while all united sing the hymn of eternal love, praising and glorifying our God, Creator and Savior.

“I don't know if all I am saying here is exactly so; if Holy Church says it in another way, believe her and not me, who am poor and ignorant; I can be mistaken. This is what I think and not what I know ... Thus we see that our Purgatory can be more or less prolonged, conform the state of grace and the degree of love of God we find ourselves in at the moment of passing from earthly life to the sphere of supernatural life, from time to eternity.”

The above reflection on Purgatory, by Sister Lucia, was published in Como vejo a Mensagem.

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART ONE

FR. GARRIGOU-LAGRANGE, O.P.

on The Sufferings of Purgatory

(taken from his book, Life Everlasting)

|

Réginald Marie Garrigou-Lagrange was February 21, 1877, Auch, France and died on February 15, 1964, Rome. He was a member of the Dominican Order of Preachers and a world renowned Catholic theologian, considered by some to be the greatest Catholic Thomistic theologian of the 20th century, along with Jacobus Ramírez, O.P., and Édouard Hugon, O.P., both also members of the Dominican Order of Preachers.

He taught at the Dominican Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Angelicum, in Rome from 1909 to 1960., at which point he retired. His great achievement was to synthesize the highly abstract writings of St Thomas Aquinas with the experiential writings of St John of the Cross, showing how they are in perfect harmony with each other. Father Garrigou-Lagrange, the leading proponent of “strict observance Thomism”, attracted wider attention when in 1946 he wrote against the Nouvelle Théologie (New Theology) theological movement, criticizing it as Modernist. He is also said to be the drafter of Pope Pius XII’s 1950 encyclical Humani Generis, subtitled “Concerning Some False Opinions Threatening to Undermine the Foundations of Catholic Doctrine.” |

LET'S GET SERIOUS!

Suffering in Purgatory and Suffering on Earth Suffering in Purgatory is greater than all suffering on Earth. Such is the doctrine of tradition, supported by theological reasoning. Tradition is expressed by St. Augustine: "That fire will be more painful than anything man can suffer in the present life." St. Isidore speaks in the same sense. According to these testimonies and others similar to them, the least pain in Purgatory surpasses the greatest sufferings of the present life. St. Bonaventure speaks somewhat differently: "In the next life, by reason of the state of the souls there retained, the purifying purgatorial suffering will be, in its kind, more severe than the greatest trials on Earth." We must understand him thus: For one and the same sin, the smallest suffering in Purgatory is greater than any corresponding suffering on Earth. But it does not follow that the least pain in Purgatory surpasses the greatest terrestrial suffering. On this point St. Bonaventure is followed by St. Robert Bellarmine. According to this last author, the privation of God is without doubt a very great suffering, but it is sweetened and consoled by the assured hope of once possessing Him. From this hope there arises an incredible joy, which grows in measure as the soul approaches the end of its exile. Many theologians, notably Suarez, rightly remark that the sufferings in Purgatory, especially the delay of the beatific vision, are of a higher order than our terrestrial sufferings, and in this sense we may say that the smallest suffering in Purgatory is more severe than the greatest suffering on Earth. The joy they have in the hope of deliverance cannot diminish the suffering they feel from deprivation of the beatific vision. We see this truth in Jesus crucified: supreme beatitude, love of God and of souls, far from diminishing His pains, augmented them. St. Catherine of Genoa speaks thus: "Souls in Purgatory unite great joy with great suffering. One does not diminish the other." She continues: "No peace is comparable to that of the souls in Purgatory, except that of the saints in Heaven. On the other hand, the souls in Purgatory endure torments which no tongue can describe and no intelligence comprehend, without special revelation." This saint, we recall, experienced on Earth the pains of Purgatory. This testimony of tradition is illustrated by the character of great saints. While they are more severe than ordinary preachers, they also have much greater love of God and souls. They show forth, not only the justice of God, but also His boundless love. A good Christian illustrates the same truth. A Christian mother, for instance, is severe in order to correct her children, but the element that predominates is sweetness and maternal goodness. Today, on the contrary, it often happens that many parents lack both severity and love. Those persons who do not undergo Purgatory on Earth will have it later on. Nor must we make too sharp a distinction between sanctification and salvation. If we neglect sanctification, we may miss salvation itself. Privation of the beatific vision is painful in the same degree as the desire of that vision is vivid. Two reasons, one negative, the other positive, show the vividness of this desire. Negatively, its desire for God is no longer retarded by the weight of the body, by the distractions and occupations of this terrestrial life. Created goods cannot distract it from the suffering it has in the privation of God. Positively, its desire of God is very intense, because the hour has arrived when it would be in the enjoyment of God if it had not placed thereunto an obstacle by the faults which it must expiate. The souls in Purgatory grasp much more clearly than we do, by reason of their infused ideas, the measureless value of the immediate vision of God, of His inamissible [incapable of being lost] possession. Further, they have intuition of themselves. Sure of their own salvation, they know with absolute certainty that they are predestined to see God, face to face. Without this delay for expiation, the moment of separation from the body would coincide with that of entrance into Heaven. In the radical order of spiritual life, then, the separated soul ought already to enjoy the beatific vision. Hence it has a hunger for God which it cannot experience here on Earth. It has failed to prepare for its rendezvous with God. Since it failed to search for Him, He now hides Himself. Analogies may be helpful. We are awaiting, with great anxiety, a friend with whom to discuss an important matter at a determined hour. If our friend is delayed, inquietude supervenes. The longer the delay, the more does inquietude grow. In the physical order, if our meal is retarded, say six hours or more, hunger grows ever more painful. If we have not eaten for three days, hunger becomes very severe. Thus, in the spiritual domain, the separated soul has an insatiable hunger for God. It understands much better than it did on Earth that its will has a depth without measure, that only God seen face to face can fill this will and draw it irresistibly. This immense void renders it more avid to see the sovereign good. This desire surpasses by far the natural desire, conditional and inefficacious, to see God. The desire of which we speak now is a supernatural desire, which proceeds from infused hope and infused charity. It is an efficacious desire, which will be infallibly fulfilled, but later. For the moment God refuses to fulfill this desire. The soul, having sought itself instead of God, cannot now find Him. Joy follows perfect activity. The greatest joy, then, follows the act of seeing God. The absence of this vision, when its hour has arrived, causes the greatest pain. Souls in Purgatory feel most vividly their impotence and poverty. A parallel on Earth appears in the saints. Like St. Paul, saints desire to die and to be with Christ. We often hear it said that in the souls in Purgatory there is an ebb and flood. Strongly drawn toward God, they are held back by the "remains of sin," which they have to expiate. They cannot rush to the goal which they so ardently desire. Love of God does not diminish their pain, but increases it. And this love is no longer meritorious. How eloquent is their title: the suffering Church! |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART TWO

SISTER LUCIA OF FATIMA

on Her Friend Amelia Who Would Be In Purgatory Until the End of the World

|

You, no doubt, remember the statement that Our Lady made to Lucia at Fatima, when she was asked about the fate of two two girls from the village who had recently died. Lucia asked Our Lady: “Is Maria das Neves in Heaven?" Our Lady replied: "Yes, she is."

The Lucia asked about the other girl, who was aged around eighteen or nineteen: "And Amelia?" This time, Our Lady said: "She will be in Purgatory until the end of the world" Amelia: until the end of the world!? Surely, a startling and perplexing communication! Some commentators have tried to tone it down, but not Lucia herself. In her last booklet, which she wrote not long before her death, Sister Lucia shares her ideas about the shocking remark of Our Lady with respect to Amelia's time in Purgatory, which may serve well as an insight to the mystery of Purgatory. Here follows Sister Lucia’s reflection and explanation: |

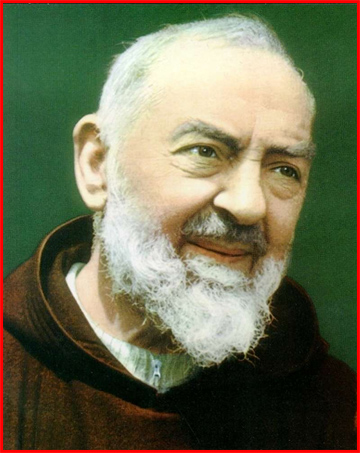

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART THREE

ST. PADRE PIO OF PIETRELCINA

His Encounters With the Poor Souls in Purgatory

|

St. Padre Pio Quotes on Purgatory

• In 1945, a Friar, Brother Modestino, asked Padre Pio to give a comparison between fire on Earth and the flames of Purgatory. Padre Pio replied: “They compare like fresh water and boiling water.” • “The souls in Purgatory pray for us, and their prayers are even more effective than ours, because they are accompanied by their suffering. So, let’s pray for them, and let’s pray them to pray for us.” • “Most of those who are saved, have to pass through Purgatory before arriving at the fullness of beatitude.” • “The souls in Purgatory repay the prayers that we say for them.” • “When we pray for the souls in Purgatory we will always get something back.” • “The souls in Purgatory pray for us.” |

Padre Pio and the Poor Souls in Purgatory

In the life of St. Padre Pio, we read of many souls from Purgatory appearing to him to beg his prayers. In 1922, Bishop Alberto Costa asked Padre Pio if he had ever seen a soul in Purgatory. “I have seen so many of them that they don’t scare me anymore.” A friar testified of the following incident: “We were all in the dining room when Padre Pio got suddenly up and walked at steady pace to the door of the convent. He opened it and started having a conversation.” The two friars that went with him didn’t see anybody and started thinking that something might be wrong with Padre Pio. On the way back to the dining area Padre Pio explained. “Don’t worry. I was talking to some souls on their way from Purgatory to Paradise. They came to thank me that I remembered them today in the Mass.” Over the decades of Padre Pio’s life millions of souls climbed Mt. Gargano to the Capuchin Friary of Our Lady of Grace to see him and to request his intercession with God. However, according to his own testimony the majority of these souls were not of the living but of the dead. Padre Pio said: “More souls of the dead from Purgatory, than of the living, climb this mountain to attend my Masses and seek my prayers.” Padre Pio reported to Padre Anastasio di Roio: “One night I was alone in the choir, and I saw a friar cleaning the altar late at night. I asked him to go to bed since it was so late. He said: ‘ I’m a friar like you. I did here my novitiate and when assigned to take care of the Altar, and I passed many times in front of the Tabernacle without making the proper reverence. For this sin I am in Purgatory, and the Lord sent me to you. You decide how much longer I have to suffer in those flames.’ I told him: until I said the Mass for him in the morning. He said: “You are cruel!” and disappeared. I still have a wound in my heart. I could have sent him immediately to Paradise, instead he had to stay one more night in the flames of Purgatory.” One evening Padre Pio was in a room, on the ground floor of the convent, turned guesthouse. He was alone and had just laid down on the cot when, suddenly, a man appeared to him wound in a black mantle. Padre Pio was amazed and arose to ask the man who he was and what he wanted. The stranger answered that he was a soul in Purgatory. “I am Pietro Di Mauro” he said “I died in a fire, on September 18, 1908, in this convent. In fact this convent, after the expropriation of the ecclesiastical goods, had been turned into a hospice for elderly. I died in the flames, while I was sleeping on my straw mattress, right in this room. I have come from Purgatory: God has granted me to come here and ask you to say Mass for me tomorrow morning. Thanks to one Mass I will be able to enter into Paradise”. Padre Pio told the man that he would say Mass for him..., “But” Padre Pio said: “I wanted to accompany him to the door of the convent. I suddenly realized I had talked to a dead person, in fact when we went out in the church square, the man that was at my side, suddenly disappeared”. Gerardo De Caro had long conversations with Padre Pio in 1943. In his written notes he testifies: “Padre Pio had an exact knowledge of the state of a soul after death, including the duration of the pain until reached total purification.” |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART FOUR

ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA

Her Account of Her Visits to Purgatory

|

Catherine, who was one of five children, was brought up piously .Her confessor relates that her penances were remarkable from the time she was eight. When she was thirteen she declared to her confessor her wish to enter the convent -- her elder sister had already taken the veil.

He pointed out to her that she was still very young and that the life of a religious was hard, but she met his objections with a "prudence and zeal" which seemed to him "not human but supernatural and divine ". So he visited the convent of her predilection, to which he was confessor, and urged the mothers to accept her as a novice. But they were resolute against transgressing their custom by receiving so young a girl. Catherine's disappointment gave her great pain. She grew up to be very lovely: "taller than most women, her head well proportioned, her face rather long but singularly beautiful and well-shaped, her complexion fair and in the flower of her youth rubicund, her nose long rather than short, her eyes dark and her forehead high and broad; every part of her body was well formed." About the time she failed to enter the convent, or a little later, her father died, and his power and possessions passed to her eldest brother Giacomo. Wishing to calm the differences between the factions into which the principal families of Genoa were divided--differences which had long entailed cruel, distracting and wearing strife--Giacomo Fiesca formed the project of marrying his young sister, Catherine, to Giuliano Adorni, son of the head of a powerful Ghibelline family. He obtained his mother's support for his plan, and found Giuliano willing to accept the beautiful, noble and rich bride proposed to him. As for Catherine herself, she would not refuse this cross laid on her at the command of her mother and eldest brother. On the 13th of January, 1463, at the age of sixteen, she was married to Giuliano Adorni. He is described as a man who wasted his substance on disorderly living. Catherine, living with him in his fine house, at first entirely refused to adopt his worldly ways, and lived "like a hermit", never going out except to hear Mass. But when she had thus spent five years, she yielded to the remonstrances of her family, and for the next five years practiced a certain involvement with the world, partaking of the pleasures customary among the women of her class, but never falling into sin. Increasingly she was irked and wearied by her husband's lack of spiritual sympathy with her, and by the distractions which kept her from God. (to be continued) |

TREATISE ON PURGATORY (Part One)

The divine fire which St. Catherine experienced in herself, made her comprehend the state of souls in Purgatory, and that they are contented there although in torment. CHAPTER 1 The state of souls in Purgatory.—They are exempt from all self-love. This holy soul, while still in the flesh, was placed in the Purgatory of the burning love of God, in whose flames she was purified from every stain, so that when she passed from this life she might be ready to enter the presence of God, her most sweet love. By means of that flame of love she comprehended in her own soul the condition of the souls of the faithful in Purgatory, where they are purified from the rust and stain of sins, from which they have not been cleansed in this world. And, as in the Purgatory of that divine flame, she was united with the divine love and satisfied with all that was accomplished in her, she was enabled to comprehend the state of the souls in Purgatory, and thus discovered concerning it: “As far as I can see, the souls in Purgatory can have no choice but to be there; this God has most justly ordained by His divine decree. They cannot turn towards themselves and say: ‘I have committed such and such sins for which I deserve to remain here;’ nor can they say: ‘Would that I had refrained from them, for then I should at this moment be in paradise;’ nor again: ‘This soul will be released before me;’ or ‘I shall be released before her.’ They retain no memory of either good or evil respecting themselves, or others, which would increase their pain. They are so contented with the divine dispositions in their regard; and with doing all that is pleasing to God in that way which He chooses, that they cannot think of themselves, though they may strive to do so. They see nothing but the operation of the divine goodness which is so manifestly bringing them to God that they can reflect neither on their own profit, nor on their hurt. Could they do so, they would not be in pure charity. They see not that they suffer their pains in consequence of their sins, nor can they for a moment entertain that thought, for should they do so it would be an active imperfection, and that cannot exist in a state where there is no longer the possibility of sin. “At the moment of leaving this life they see why they are sent to Purgatory, but never again, otherwise they would still retain something private, which has no place there. Being established in charity, they can never deviate therefrom by any defect, and have no will or desire, save the pure will of pure love, and can swerve from it in nothing. They can neither commit sin, nor merit by refraining from it.” CHAPTER 2 The joy of souls in Purgatory.—The saint illustrates their ever increasing vision of God.—The difficulty of speaking about their state. “There is no peace to be compared with that of the souls in Purgatory, save that of the saints in paradise, and this peace is ever augmented by the inflowing of God into these souls, which increases in proportion as the impediments to it are removed. The rust of sin is the impediment, and this the fire continually consumes, so that the soul in this state is continually opening itself to admit the divine communication. As a covered surface can never reflect the sun, not through any defect in that orb, but simply from the resistance offered by the covering, so, if the covering be gradually removed, the surface will by little and little be opened to the sun and will more and more reflect His light. “So it is with the rust of sin, which is the covering of the soul. In Purgatory the flames incessantly consume it, and as it disappears, the soul reflects more and more perfectly the true sun who is God. Its contentment increases as this rust wears away, and the soul is laid bare to the divine ray, and thus one increases and the other decreases, until the time is accomplished. The pain never diminishes, although the time does, but as to the will, so united is it to God by pure charity, and so satisfied to be under His divine appointment, that these souls can never say their pains are pains. “On the other hand, it is true that they suffer torments which no tongue can describe nor any intelligence comprehend, unless it be revealed by such a special grace as that which God has vouchsafed to me, but which I am unable to explain. And this vision which God revealed to me has never departed from my memory. I will describe it as far as I am able, and they whose intellects our Lord will deign to open will understand me. CHAPTER 3 Separation from God is the greatest pain of Purgatory.—In this, Purgatory differs from Hell. “The source of all suffering is either Original or Actual Sin. God created the soul pure, simple, free from every stain, and with a certain beatific instinct toward Himself. It is drawn aside from Him by Original Sin, and when Actual Sin is afterwards added, this withdraws it still farther, and, ever as it removes from Him, its sinfulness increases, because its communication with God grows less and less. “And because there is no good except by participation with God, who, to the irrational creatures imparts Himself as He wills and in accordance with His divine decree, and never withdraws from them, but to the rational soul He imparts Himself more or less, according as He finds her more or less freed from the hindrances of sin, it follows that, when He finds a soul that is returning to the purity and simplicity in which she was created, He increased in her the beatific instinct, and kindles in her a fire of charity so powerful and vehement, that it is insupportable to the soul to find any obstacle between her and her end; and the clearer vision she has of these obstacles the greater is her pain. “Since the souls in Purgatory are freed from the guilt of sin, there is no barrier between them and God save only the pains they suffer, which delay the satisfaction of their desire. And when they see how serious is even the slightest hindrance, which the necessity of justice causes to check them, a vehement flame kindles within them, which is like that of Hell. They feel no guilt however, and it is guilt which is the cause of the malignant will of the condemned in Hell, to whom God does not communicate His goodness, and thus they remain in despair and with a will forever opposed to the good will of God. |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART FIVE

ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA (continued)

Her Account of Her Visits to Purgatory

|

Catherine, who was one of five children, was brought up piously .Her confessor relates that her penances were remarkable from the time she was eight. When she was thirteen she declared to her confessor her wish to enter the convent -- her elder sister had already taken the veil.

He pointed out to her that she was still very young and that the life of a religious was hard, but she met his objections with a "prudence and zeal" which seemed to him "not human but supernatural and divine ". So he visited the convent of her predilection, to which he was confessor, and urged the mothers to accept her as a novice. But they were resolute against transgressing their custom by receiving so young a girl. Catherine's disappointment gave her great pain. She grew up to be very lovely: "taller than most women, her head well proportioned, her face rather long but singularly beautiful and well-shaped, her complexion fair and in the flower of her youth rubicund, her nose long rather than short, her eyes dark and her forehead high and broad; every part of her body was well formed." About the time she failed to enter the convent, or a little later, her father died, and his power and possessions passed to her eldest brother Giacomo. Wishing to calm the differences between the factions into which the principal families of Genoa were divided--differences which had long entailed cruel, distracting and wearing strife--Giacomo Fiesca formed the project of marrying his young sister, Catherine, to Giuliano Adorni, son of the head of a powerful Ghibelline family. He obtained his mother's support for his plan, and found Giuliano willing to accept the beautiful, noble and rich bride proposed to him. As for Catherine herself, she would not refuse this cross laid on her at the command of her mother and eldest brother. On the 13th of January, 1463, at the age of sixteen, she was married to Giuliano Adorni. He is described as a man who wasted his substance on disorderly living. Catherine, living with him in his fine house, at first entirely refused to adopt his worldly ways, and lived "like a hermit", never going out except to hear Mass. But when she had thus spent five years, she yielded to the remonstrances of her family, and for the next five years practiced a certain involvement with the world, partaking of the pleasures customary among the women of her class, but never falling into sin. Increasingly she was irked and wearied by her husband's lack of spiritual sympathy with her, and by the distractions which kept her from God. (to be continued) |

TREATISE ON PURGATORY (Part Two)

The divine fire which St. Catherine experienced in herself, made her comprehend the state of souls in Purgatory, and that they are contented there although in torment. CHAPTER 4 The difference between the state of the souls in Hell and that of those in Purgatory.—Reflections of the saint upon those who neglect their salvation. “It is evident that the revolt of man’s will, from that of God, constitutes sin, and while that revolt continues, man’s guilt remains. Those, therefore, that are in Hell, having passed from this life with perverse wills, their guilt is not remitted, nor can it be, since they are no longer capable of change. When this life is ended, the soul remains forever confirmed either in good or evil according as she has here determined. As it is written: Where I shall find thee, that is, at the hour of death, with the will either fixed on sin or repenting of it, there I will judge thee. From this judgment there is no appeal, for after death the freedom of the will can never return, but the will is confirmed in that state in which it is found at death. The souls in Hell, having been found at that hour with the will to sin, have the guilt and the punishment always with them, and although this punishment is not so great as they deserve, yet it is eternal. Those in Purgatory, on the other hand, suffer the penalty only, for their guilt was cancelled at death, when they were found hating their sins and penitent for having offended the divine goodness. And this penalty has an end, for the term of it is ever approaching. O misery beyond all misery, and the greater because in his blindness, man regards it not! “The punishment of the damned is not, it is true, infinite in degree, for the all lovely goodness of God shines even into Hell. He who dies in mortal sin merits infinite woe for an infinite duration; but the mercy of God has only made the time infinite, and mitigated the intensity of the pain. In justice He might have inflicted much greater punishment than He has done. “Oh, what peril attaches to sin willfully committed! For it is so difficult for man to bring himself to penance, and without penitence guilt remains and will ever remain, so long as man retains unchanged the will to sin, or is intent upon committing it. CHAPTER 5 Of the peace and joy which are found in Purgatory “The souls in Purgatory are entirely conformed to the will of God; therefore, they correspond with His goodness, are contented with all that He ordains, and are entirely purified from the guilt of their sins. They are pure from sins, because they have in this life abhorred them and confessed them with true contrition, and for this reason God remits their guilt, so that only the stains of sin remain, and these must be devoured by the fire. Thus freed from guilt and united to the will of God, they see Him clearly according to that degree of light which He allows them, and comprehend how great a good is the fruition of God, for which all souls were created. Moreover, these souls are in such close conformity to God, and are drawn so powerfully toward Him by reason of the natural attraction between Him and the soul, that no illustration or comparison could make this impetuosity understood in the way in which my spirit conceives it by its interior sense. Nevertheless I will use one which occurs to me. CHAPTER 6 A comparison to express with how great violence of love the souls in Purgatory desire to enjoy God. “Let us suppose that in the whole world there were but one loaf to appease the hunger of every creature, and that the bare sight of it would satisfy them. Now man, when in health, has by nature the instinct for food, but if we can suppose him to abstain from it and neither die, nor yet lose health and strength, his hunger would clearly become increasingly urgent. In this case, if he knew that nothing but the loaf would satisfy him, and that until he reached it his hunger could not be appeased, he would suffer intolerable pains, which would increase as his distance from the loaf diminished; but if he were sure that he would never see it, his Hell would be as complete as that of the damned souls, who, hungering after God, have no hope of ever seeing the bread of life. But the souls in Purgatory have an assured hope of seeing Him and of being entirely satisfied; and therefore they endure all hunger and suffer all pain until that moment when they enter into eternal possession of this bread, which is Jesus Christ, our Lord, our Saviour, and our Love. |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART SIX

ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA (continued)

Her Account of Her Visits to Purgatory

|

THE LIFE OF ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA : Part 2

Her conversion is dated from the eve of St. Bernard, 1474, when she visited the church of St. Bernard, in Genoa, and prayed, so intolerable had life in the world become to her, that she might have an illness which would keep her three months in bed. Her prayer was not granted but her longing to leave the world persisted. Two days later she visited her sister Limbania in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, and at Limbania's instance returned there on the morrow to make her confession to the nuns' confessor. Suddenly, as she was kneeling down at the confessional, "her heart was wounded by a dart of God's immense love, and she had a clear vision of her own wretchedness and faults and the most high goodness of God. She fell to the ground, all but swooning", and from her heart rose the unuttered cry, "No more of the world for me! No more sin!" The confessor was at this moment called away, and when he came back she could speak again, and asked and obtained his leave to postpone her confession. Then she hurried home, to shut herself up in the most secluded room in the house, and for several days she stayed there absorbed by consciousness of her own wretchedness and of God's mercy in warning her. She had a vision of Our Lord, weighed down by His Cross and covered with blood, and she cried aloud, "O Lord, I will never sin again; if need be, I will make public confession of my sins." After a time, she was inspired with a desire for Holy Communion which she fulfilled on the feast of the Annunciation. She now entered on a life of prayer and penance. She obtained from her husband a promise, which he kept, to live with her as a brother. She made strict rules for herself--to avert her eyes from sights of the world, to speak no useless words, to eat only what was necessary for life, to sleep as little as possible and on a bed in which she put briers and thistles, to wear a rough hair shirt. Every day she spent six hours in prayer. She rigorously mortified her affections and will. Soon, guided by the Ladies of Mercy, she was devoting herself to the care of the sick poor. In her plain dress she would go through the streets and byways of Genoa, looking for poor people who were ill, and when she found them she tended them and washed and mended their filthy rags. Often she visited the hospital of St. Lazarus, which harbored incurables so diseased as to be horrible to the sight and smell, many of them embittered. In Catherine they aroused not disgust but charity; she met their insults with unfailing gentleness. Her earliest biography gives details of her religious practices. From the time of her conversion she hungered insatiably for the Holy Eucharist, and the priests admitted her to the privilege, very rare in that period, of daily communion. For twenty-three years, beginning in the third year after her conversion, she fasted completely throughout Lent and Advent, except that at long intervals she drank a glass of water mixed with salt and vinegar to remind herself of the drink offered to Our Lord on the cross, and during these fasts she enjoyed exceptional health and vigor. For twenty-five years after her conversion she had no spiritual director except Our Lord Himself. Then, when she had fallen into the illness which afflicted the last ten years of her life, she felt the need for human help, and a priest named Cattaneo Marabotto, who had a position of authority in the hospital in which she was then working, became her confessor. Some years after her conversion her husband was received into the Third Order of St. Francis, and afterwards he helped her in her works of mercy. (to be continued) |

TREATISE ON PURGATORY (Part Three)

The divine fire which St. Catherine experienced in herself, made her comprehend the state of souls in Purgatory, and that they are contented there although in torment. CHAPTER 7 Of the marvelous wisdom of God in the creation of Purgatory and of Hell. “As the purified spirit finds no repose but in God, for whom it was created, so the soul in sin can rest nowhere but in Hell, which by, reason of its sins, has become its end. Therefore, at that instant in which the soul separates from the body, it goes to its prescribed place, needing no other guide than the nature of the sin itself, if the soul has parted from the body in mortal sin. And if the soul were hindered from obeying that decree (proceeding from the justice of God), it would find itself in a yet deeper Hell, for it would be outside of the divine order, in which mercy always finds place and prevents the full infliction of all the pains the soul has merited. Finding, therefore, no spot more fitting, nor any in which her pains would be so slight, she casts herself into her appointed place. “The same thing is true of Purgatory: the soul, leaving the body, and not finding in herself that purity in which she was created, and seeing also the hindrances which prevent her union with God, conscious also that Purgatory only can remove them, casts herself quickly and willingly therein. And if she did not find the means ordained for her purification, she would instantly create for herself a Hell worse than Purgatory, seeing that by reason of this impediment she is hindered from approaching her end, which is God; and this is so great an ill that in comparison with it the soul esteems Purgatory as nothing. True it is, as I have said, like Hell; and yet, in comparison with the loss of God it is as nothing. CHAPTER 8 Of the necessity of Purgatory, and of its terrific character “I will say furthermore: I see that as far as God is concerned, paradise has no gates, but he who will may enter. For God is all mercy, and His open arms are ever extended to receive us into His glory. But I see that the divine essence is so pure—purer than the imagination can conceive—that the soul, finding in itself the slightest imperfection, would rather cast itself into a thousand Hells than appear, so stained, in the presence of the divine majesty. Knowing, then, that Purgatory was intended for her cleaning, she throws herself therein, and finds there that great mercy, the removal of her stains. “The great importance of Purgatory, neither mind can conceive nor tongue describe. I see only that its pains are as great as those of Hell; and yet I see that a soul, stained with the slightest fault, receiving this mercy, counts its pains as naught in comparison with this hindrance to her love. And I know that the greatest misery of the souls in Purgatory is to behold in themselves aught that displeases God, and to discover that, in spite of His goodness, they had consented to it. And this is because, being in the state of grace, they see the reality and the importance of the impediments which hinder their approach to God. CHAPTER 9 How God and the soul reciprocally regard each other in Purgatory.—The saint confesses that she has no words to express these things. “All these things that I have said, in comparison with those which have been represented to my mind (as far as I have been able to comprehend them in this life), are of such magnitude that every idea, every word, every feeling, every imagination, all the justice and all the truth that can be said of them, seem false and worthless, and I remain confounded at the impossibility of finding words to describe them. “I behold such a great conformity between God and the soul, that when He finds her pure as when His divine majesty first created her He gives her an attractive force of ardent love which would annihilate her if she were not immortal. He so transforms her into Himself that, forgetting all, she no longer sees aught beside Him; and He continues to draw her toward Him, inflames her with love, and never leaves her until He has brought her to that state from whence she first came forth, that is, to the perfect purity in which she was created. “When the soul beholds within herself the amorous flame by which she is drawn toward her sweet Master and her God, the burning heat of love overpowers her and she melts. Then, in that divine light she sees how God, by His great care and constant providence, never ceases to attract her to her last perfection, and that He does so through pure love alone. She sees, too, that she herself, clogged by sin, cannot follow that attraction toward God, that is, that reconciling glance which He casts upon her that He may draw her to Himself. Moreover, a comprehension of that great misery, which it is to be hindered from gazing upon the light of God, is added to the instinctive desire of the soul to be wholly free to yield herself to that unifying flame. I repeat, it is the view of all these things which causes the pain of the suffering souls in Purgatory, not that they esteem their pains as great (cruel though they be), but they count as far worse, that opposition, which they find in themselves, to the will of that God, whom they behold burning for them with so ardent and so pure a love. “This love, with its unifying regard, is ever drawing these souls, as if it had no other thing to do; and when the soul beholds this, if she could find a yet more painful Purgatory in which she could be more quickly cleansed, she would plunge at once therein, impelled by the burning, mutual love between herself and God. |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART SEVEN

ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA (continued)

Her Account of Her Visits to Purgatory

|

THE LIFE OF ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA : Part 3

The time came when the directors of the great hospital in Genoa asked Catherine to superintend the care of the sick in this institution. She accepted, and hired near the hospital a poor house in which she and her husband lived out the rest of their days. Her prayers were still long and regular and her raptures frequent, but she so arranged that neither her devotions nor her ecstasies interfered with her care of the sick. Although she was humbly submissive even to the hospital servants, the directors saw the value of her work and appointed her rector of the hospital with unlimited powers. In 1497, she nursed her husband through his last illness. In his will he extolled her virtues and left her all his possessions. Mrs. Charlotte Balfour underlined in her copy of the saint’s works an indicative extract from her teaching. “We should not wish for anything but what comes to us from moment to moment,” Saint Catherine told her spiritual children, “exercising ourselves none the less for good. For he who would not thus exercise himself, and await what God sends, would tempt God. When we have done what good we can, let us accept all that happens to us by Our Lord’s ordinance, and let us unite ourselves to it by our will. Who tastes what it is to rest in union with God will seem to himself to have won to Paradise even in this life.” She was still only fifty-three years old when she fell ill, worn out by her life of ecstasies, her burning love for God, labor for her fellow creatures and her privations; during her last ten years on earth she suffered much. She died on the 15th of September, 1510, at the age of sixty-three. The public cult rendered to her was declared legitimate on the 6th of April, 1675. The process for her canonization was instituted by the directors of the hospital in Genoa where she had worked. Her heroic virtue and the authenticity of many miracles attributed to her having been proved, the bull for her canonization was issued by Pope Clement XII, on the 30th of April, 1737. Saint Catherine’s authorship of the Treatise on Purgatory has never been disputed. But Baron von Hugel in his monumental work the “Mystical Element in Religion as Studied in Saint Catherine of Genoa and her Friends” concludes convincingly, after a meticulous examination of the “Dialogue of the Blessed and Seraphic Saint Catherine of Genoa,” that its author was Battista Vernazza: “The entire Dialogue then is the work of Battista Vernazza.” Thus this work is not, as has been thought, the saint’s spiritual autobiography, nor indeed does it ever claim to be other than what it is, her spiritual biography. It is the life of her soul, dramatized by a younger woman who had known her and her intimates, who had a singular devotion to her, and who was peculiarly qualified to understand her experience. (to be continued) |

TREATISE ON PURGATORY (Part Four)

The divine fire which St. Catherine experienced in herself, made her comprehend the state of souls in Purgatory, and that they are contented there although in torment. CHAPTER 10 How God makes use of Purgatory to complete the purification of the soul.—That she acquires therein a purity so great that if she were yet to remain after her purification she would cease to suffer. “From that furnace of divine love I see rays of fire dart like burning lamps towards the soul; and so violent and powerful are they that both soul and body would be utterly destroyed, if that were possible. These rays perform a double office; they purify and they annihilate. “Consider gold: the oftener it is melted, the more pure does it become; continue to melt it and every imperfection is destroyed. This is the effect of fire on all materials. The soul, however, cannot be annihilated in God, but in herself she can, and the longer her purification lasts, the more perfectly does she die to herself, until at length she remains purified in God. “When gold has been completely freed from dross, no fire, however great, has any further action on it, for nothing but its imperfections can be consumed. So it is with the divine fire in the soul. God retains her in these flames until every stain is burned away, and she is brought to the highest perfection of which she is capable, each soul in her own degree. And when this is accomplished, she rests wholly in God. Nothing of herself remains, and God is her entire being. When He has thus led her to Himself and purified her, she is no longer passable, for nothing remains to be consumed. If when thus refined she should again approach the fire she would feel no pain, for to her it has become the fire of divine love, which is life eternal and which nothing mars. CHAPTER 11 The desire of souls in Purgatory to be purified from every stain of sin.—The wisdom of God in veiling from them their defects. “At her creation the soul received all the means of attaining perfection of which her nature was capable, in order that she might conform to the will of God and keep herself from contracting any stain; but being directly contaminated by Original Sin she loses her gifts and graces and even her life. Nor can she be regenerated save by the help of God, for even after baptism her inclination to evil remains, which, if she does not resist it, disposes and leads her to mortal sin, through which she dies anew. “God again restores her by a further special grace; yet, she is still so sullied and so bent on herself, that to restore her to her primitive innocence, all those divine operations which I have described are needful, and without them she could never be restored. When the soul has reentered the path which leads to her first estate, she is inflamed with so burning a desire to be transformed into God, that in it she finds her Purgatory. Not, indeed, that she regards her Purgatory as being such, but this desire, so fiery and so powerfully repressed, becomes her Purgatory. “This final act of love accomplishes its work alone, finding the soul with so many hidden imperfections, that the mere sight of them, were it presented to her, would drive her to despair. This last operation, however, consumes them all, and when they are destroyed God makes them known to the soul to make her understand the divine action by which her purity was restored. CHAPTER 12 How joy and suffering are united in Purgatory “That which man judges to be perfect, in the sight of God is defect. For all the works of man, which appear faultless when he considers them feels, remembers, wills and understands them, are, if he does not refer them to God, corrupt and sinful. For, to the perfection of our works it is necessary that they be wrought in us but not of us. In the works of God it is He that is the prime mover, and not man. “These works, which God effects in the soul by Himself alone, which are the last operations of pure and simple love in which we have no merit, so pierce and inflame the soul that the body which envelops her seems to be hiding a fire, or like one in a furnace, who can find no rest but death. It is true that the divine love which overwhelms the soul gives, as I think, a peace greater than can be expressed; yet this peace does not in the least diminish her pains, nay, it is love delayed which occasions them, and they are greater in proportion to the perfection of the love of which God has made her capable. “Thus have these souls in Purgatory great pleasure and great pain; nor does the one impede the other. |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART EIGHT

ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA (continued)

Her Account of Her Visits to Purgatory

|

THE LIFE OF ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA : Part 4

Baron von Hugel believed that Saint Catherine first became acquainted with the Genoese notary, Ettore Vernazza, during the epidemic in Genoa in 1493, that is nineteen years after her conversion, when she was forty-six years old and he in his early twenties. She wrote of “a great compassion he had conceived when still very young, at the time the pestilence raged in Genoa, when he used to go about to help the poor”. Von Hugel describes him, after profound study of his life and works, as “a man of fine and keen, deep and world-embracing mind and heart, of an overflowing, ceaseless activity, and of a will of steel”. He was “the most intimate, certainly the most perceptive of Catherine’s disciples” and with Cattaneo Marabotto wrote the earliest life of her. In 1496 he married Bartolomea Ricci, and they had three daughters of whom the eldest, Tommasa, had Saint Catherine for godmother. Little Tommasa was a sensitive, loving, bright child with a turn for writing, as she shewed in a few simple lines of verse which she wrote to her “most holy protectress” and “adored mother” when she was only ten. Was she addressing her godmother, or her mother in the flesh who died not long afterwards? Her father, after his wife’s death, sent her and her little sister Catetta to board in that convent of Augustinian canonesses in which Saint Catherine had not been allowed to take the veil. Perhaps the nuns had been taught by the saint that very young girls may have a true vocation to religion, for Tommasa was only thirteen when, on the 24th of June, 1510, she received in their house the habit of an Augustinian Canoness of the Lateran and changed her name to Battista. She spent all the rest of her ninety years on earth in that convent in Genoa. Twelve weeks after her reception Saint Catherine died, and Baron von Hugel tentatively identifies Battista with an unnamed nun to whom, and to six other friends and disciples of the saint, Battista’s father among them, “intimations and communications of her passage and instant complete union with God” were vouchsafed at the moment of her death. Battista’s literary remains include many letters, poetry--both spiritual canticles and sonnets, and several volumes of spiritual dissertations in which are “all but endless parallels and illustrations” to the teachings of Saint Catherine. She wrote also three sets of “Colloquies,” and in one of them relates certain of her own spiritual experiences. In all her writings, but especially in these narrations, Baron von Hugel notes the influence of Catherine’s doctrine and spiritual practices. (to be continued) |

TREATISE ON PURGATORY (Part Five)

The divine fire which St. Catherine experienced in herself, made her comprehend the state of souls in Purgatory, and that they are contented there although in torment. CHAPTER 13 The souls in Purgatory are not in a state to merit.—How they regard the suffrages offered for them in this world. “If by repentance, the souls in Purgatory could purify themselves, a moment would suffice to cancel their whole debt, so overwhelming would be the force of the contrition produced by the clear vision they have of the magnitude of every obstacle which hinders them from God, their love and their final end. “And, know for certain that not one farthing of their debt is remitted to these souls. This is the decree of divine justice; it is thus that God wills. But, on the other hand, these souls have no longer any will apart from that of God, and can neither see nor desire aught but by His appointment. “And if pious offerings be made for them, by persons in this world, they cannot now note them with satisfaction, unless, indeed, in reference to the will of God and the balance of His justice, leaving to Him the ordering of the whole, who repays Himself as best pleases His infinite goodness. Could they regard these alms apart from the divine will concerning them, this would be a return to self, which would shut from their view the will of God, and that would be to them like Hell. Therefore they are unmoved by whatever God gives them, whether it be pleasure or pain, nor can they ever again revert to self.” CHAPTER 14 Of the submission of the souls in Purgatory to the will of God “So hidden and transformed in God are they, that they rest content with all His holy will. And if a soul, retaining the slightest stain, were to draw near to God in the beatific vision, it would be to her a more grievous injury, and inflict more suffering, than Purgatory itself. Nor could God Himself, who is pure goodness and supreme justice, and the sight of God, not yet entirely satisfied (so long as the least possible purification remained to be accomplished) would be intolerable to her, and she would cast herself into the deepest Hell rather than stand before Him and be still impure.” CHAPTER 15 Reproaches of the soul in Purgatory to persons in this world "And thus this blessed Soul, illuminated by the divine ray, said: “Would that I could utter so strong a cry that it would strike all men with terror, and say to them: O wretched beings! Why are you so blinded by this world that you make, as you will find at the hour of death, no provision for the great necessity that will then come upon you? “You shelter yourselves beneath your hope in the mercy of God, which you unceasingly exalt, not seeing that it is your resistance to His great goodness which will be your condemnation. His goodness should constrain you to do His will, not encourage you to persevere in your own. Since His justice is unfailing it must needs be in some way fully satisfied. “Have not the boldness to say: ‘I will go to confession and gain a plenary indulgence and thus I shall be saved.’ Remember that the full confession and entire contrition which are requisite to gain a plenary indulgence are not easily attained. Did you know how hardly they are come by, you would tremble with fear and be more sure of losing than of gaining them. |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART NINE

ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA (final part)

Her Account of Her Visits to Purgatory

|

THE LIFE OF ST. CATHERINE OF GENOA : Part 5

The Dialogue reproduces the incidents of the saint’s spiritual life as these are recorded in her earliest biography, and its doctrine is that embodied in the Treatise on Purgatory and in her recorded sayings, from which even its language is in large part derived. That its matter has passed through another mind, Battista’s, gives it an added interest: there is the curious, vivid dramatization; there is, in some passages, a poignant and individual quality; and there is an insight which proves that Battista herself was also a mystic, one who had spent all her days in the spiritual companionship of Saint Catherine. We are shewn not only the saint but also her reflection in the mirror which was Battista’s mind. “A person”, says Von Hugel, speaking of Battista at the time when she wrote the Dialogue“living now thirty-eight years after Catherine’s death, in an environment of a kind to preserve her memory green.... Battista, the goddaughter of the heroine of the work, and the eldest, devoted daughter of the chief contributor to the already extant biography; a contemplative with a deep interest in, and much practical experience of, the kind of spirituality to be portrayed and the sort of literature required; a nun during thirty-eight years in the very convent where Catherine’s sister, one of its foundresses, had lived and died, and where Catherine herself had desired to live and where her conversion had taken place.” The Dialogue, long generally accepted as Catherine’s own account of her spiritual life, has been allowed by the highest authorities to embody, with her Treatise on Purgatory, the saint’s doctrine. These two treatises and the earliest biography, translated into several languages, spread that doctrine and devotion to her throughout the Catholic world in the centuries between her death and her canonization. The bull which canonized her alludes to the Dialogue as an exposition of her doctrine: “In her admirable Dialogue she depicts the dangers to which a soul bound by the flesh is exposed.” The Viscount Theodore Marie de Bussierne includes the Dialogue with the Treatise on Purgatory in his translation into French of the saint’s works, published in 1860. It was from this translation that Mrs. Charlotte Balfour translated the first half of the Dialogue into English. She meant to make an English version of all the saint’s works but had worked only on the Dialogue at the time of her death. Her work has been carefully collated with the Italian original and revised where necessary, the edition used being that included in the beautiful “Life and Works” of Saint Catherine which was printed in Rome in 1737, the year of her canonization, by Giovanni Battista de Caporali, and dedicated to Princess Vittoria Altoviti de’ Corsini, the Pope’s niece. As here printed, the whole Dialogue may be regarded as translated from Battista Venazza’s original work. Mrs. Balfour would certainly have wished to acknowledge her debt to Monsieur de Bussierne’s French version. The latter part of the Dialogue and the whole Treatise on Purgatory have been directly translated from the 1737 Italian edition of the saint’s works. Saint Catherine’s earliest biography concludes with the following words: “It remains for us to pray the Lord, of His great goodness and by the intercession of this glorious Seraphim, to give us His love abundantly, that we may not cease to grow in virtue, and may at last win to eternal beatitude with God who lives and reigns for ever and ever.” THE END |

TREATISE ON PURGATORY (Part Six)

The divine fire which St. Catherine experienced in herself, made her comprehend the state of souls in Purgatory, and that they are contented there although in torment. CHAPTER 16 Showing that the sufferings of the souls in Purgatory do not prevent their peace and joy. “I see that the souls in Purgatory behold a double operation. The first is that of the mercy of God; for while they suffer their torments willingly, they perceive that God has been very good to them, considering what they have deserved and how great are their offenses in His eyes. For if His goodness did not temper justice with mercy (satisfying it with the precious blood of Jesus Christ), one sin alone would deserve a thousand Hells. They suffer their pains so willingly that they would not lighten them in the least, knowing how justly they have been deserved. They resist the will of God no more than if they had already entered upon eternal life. “The other operation is that satisfaction they experience in beholding how loving and merciful have been the divine decrees in all that regards them. In one instant God impresses these two things upon their minds, and as they are in grace they comprehend them as they are, yet each according to her capacity. They experience thence a great and never-failing satisfaction which constantly increases as they approach to God. They see all things, not in themselves, nor by themselves, but as they are in God, on whom they are more intent than on their sufferings. For the least vision they can have of God overbalances all woes and all joys that can be conceived. Yet their joy in God does by no means abate their pain. CHAPTER 17 Which concludes with an application of all that has been said concerning the souls in Purgatory to what the saint experiences in her own soul. “This process of purification, to which I see the souls in Purgatory subjected, I feel within myself, and have experienced it for the last two years. Every day I see and feel it more clearly. My soul seems to live in this body as in a Purgatory which resembles the true Purgatory, with only the difference that my soul is subjected to only so much suffering as the body can endure without dying, but which will continually and gradually increase until death. “I feel my spirit alienated from all things (even spiritual ones) that might afford it nourishment, or give it consolation. I have no relish for either temporal or spiritual goods through the will, the understanding, or the memory, nor can I say that I take greater satisfaction in this thing than in that. “I have been so besieged interiorly, that all things which refreshed my spiritual or my bodily life have been gradually taken from me, and as they departed, I learned that they were all sources of consolation and support. Yet, as soon as they were discovered by the spirit they became tasteless and hateful; they vanish and I care not to prevent it. This is because the spirit instinctively endeavors to rid itself of every hindrance to its perfection, and so resolutely that it would rather go to Hell than fail in its purpose. It persists, therefore, in casting off all things by which the inner man might nourish himself, and so jealously guards him, that no slightest imperfection can creep in without being instantly detected and expelled. “As for the outward man, for the reason that the spirit has no correspondence with it, it is so oppressed that nothing on earth can give it comfort according to its human inclinations. No consolation remains to it but God, who, with great love and mercy accomplishes this work for the satisfaction of His justice. I perceive all this, and it gives me a great peace and satisfaction; but this satisfaction does by no means diminish my oppression or my pain. Nor could there possibly befall me a pain so great, that it could move me to swerve from the divine ordination, or leave my prison, or wish to leave it until God is satisfied, nor could I experience any woe so great as would be an escape from His divine decree, so merciful and so full of justice do I find it. “I see these things clearly, but words fail me to describe them as I wish. What I have described is going on within my spirit, and therefore I have said it. The prison which detains me is the world; my chains, the body; the soul, illuminated by grace, comprehends how great a misery it is to be hindered from her final end, and she suffers greatly because she is very tender. She receives from God, by His grace, a certain dignity which assimilates her to Him, nay, which makes her one with Him by the participation of His goodness. And as it is impossible for God to suffer any pain, it is so also with those happy souls who are drawing nearer to Him. The more closely they approach Him the more fully do they share in His perfections. “Any delay, then, causes the soul intolerable pain. The pain and the delay prevent the full action both of what is hers by nature, and of that which has been revealed to her by grace; and, not able as yet to possess and still essentially capable of possessing, her pain is great in proportion to her desire of God. The more perfectly she knows Him, the more ardent is her desire, and the more sinless is she. The impediments that bar her from Him become all the more terrible to her, because she is so wholly bent on Him, and when not one of these is left she knows Him as He is. “As a man who suffers death, rather than offend God, does not become insensible to the pains of death, but is so illuminated by God that his zeal for the divine honor is greater than his love for life, so the soul, knowing the will of God, esteems it more than all outward or inward torments, however terrible; and this for the reason that God, for whom and by whom the work is done, is infinitely more desirable than all else that can be known or understood. And inasmuch as God keeps the soul absorbed in Himself and in His majesty, even though it be only in a slight degree, yet she can attach no importance to anything beside. She loses in Him all that is her own, and can neither see nor speak, nor yet be conscious of any injury or pain she suffers, but as I have said before it is all understood in one moment as she passes from this life. And finally, to conclude all, understand well, that in the almighty and merciful God, all that is in man is wholly transformed, and that Purgatory purifies him.” THE END |

SAINTS & THEOLOGIANS ON PURGATORY ~ PART TEN

ST. LEONARD OF PORT MAURICE

From his book The Hidden Treasure of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass

|

A Mass Could Clear-Out Purgatory!