| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON ANY OTHER HOLY GHOST PAGE YOU WISH TO READ

Links will be activated as articles appear on those pages

HOLY GHOST HOMEPAGE (General Articles)

| INTRODUCTION TO THE SEVEN GIFTS OF THE HOLY GHOST (a very brief coverage of all seven Gifts) |

| Gift of Fear | Gift of Piety | Gift of Knowledge | Gift of Fortitude | Gift of Counsel | Gift of Understanding | Gift of Wisdom |

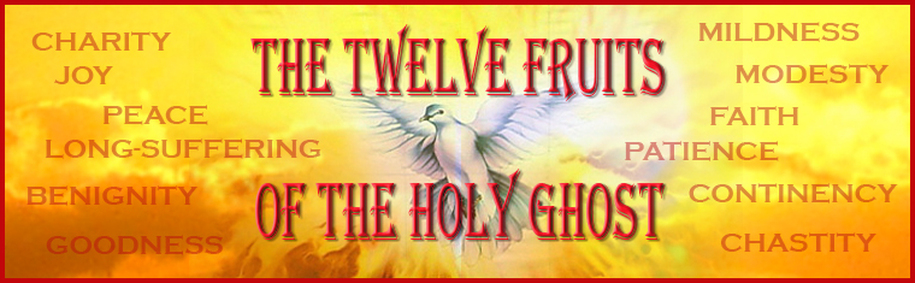

| THE TWELVE FRUITS OF THE HOLY GHOST (a brief coverage of all 12 Fruits) |

| PRAYERS TO THE HOLY GHOST | NOVENA TO THE HOLY GHOST |

INTRODUCTION TO THE TWELVE FRUITS OF THE HOLY GHOST

|

There are few works on the operations of the Holy Ghost; there are fewer still on the Twelve Fruits. Hopefully this will go a little way to supplying the need—even if we are blind to the need.

The Fruits of the Holy Ghost are displayed in everyone who is in the state of grace. But the degree of fruition corresponds to the degree of grace arrived at by the soul. There are innumerable degrees, ranging from the newly‑formed fruit to mature perfection, and even further to supreme excellence. So that in a discussion of the Twelve Fruits we shall expect to find something for everyone; while the advancing soul will perhaps profit most from it, the beginner is not forgotten. By the Christian, in the world, the Fruits are manifested in his daily activities. It is true that devotion to the Holy Ghost is an interior one. But its object is to make the Christian Christ‑like. And just as Christ went about doing good, so does the Christian, who is attentive to the Holy Ghost Who dwells within him. The Twelve Fruits are not just aspects of the Christian life which are interesting to speculate on. They have a practical application, which it is the purpose of these articles to show. Some spiritual writers use the term “Fruits of the Holy Ghost” to cover and include all the supernatural virtues, or more precisely to the acts of all these virtues, inasmuch as they are the results of the mysterious workings of the Holy Ghost in our souls by means of His grace. But, with St. Thomas, (Summa Theologica, Ia-IIae q. 70. art. 2), the term is restricted to mean only those supernatural works that are done joyfully and with peace of soul. |

This is the sense in which most authors apply the term to the list mentioned by St. Paul (Galatians 5:22-23): “But the fruit of the Spirit is, Charity, Joy, Peace, Patience, Benignity, Goodness, Longanimity, Mildness, Faith, Modesty, Continency, Chastity.”

There is no doubt that this list of twelve—three of the twelve are omitted in several Greek and Latin versions of the Bible—is not to be taken in a strictly limited sense, but as capable of being extended to include all virtuous acts of a similar character. That is why the St. Thomas says: “Every virtuous act which man performs with pleasure is a fruit.” The fruits of the Holy Ghost are not permanent qualities always residing in the soul, but they are isolated and separate acts. They cannot, therefore, be confused with the Theological and Cardinal Virtues and the Gifts of the Holy Ghost. The Fruits could be said to be the effects of the Virtues and Gifts, like a child of two parents, or as streams flowing out of their source, the mountain lake. The charity, patience, mildness, etc., of which the Apostle speaks in the above passage (Galatians 5:22-23), are not therefore the virtues themselves, but rather the acts or operations or fruits of those virtues. Furthermore, in order that these acts may fully justify their metaphorical name of “fruits”, they must belong to that class which are performed with ease and pleasure; in other words, the difficulty involved in performing them must disappear, giving way to a presence of the delight and satisfaction resulting from good that it performed. |

Scroll down for the Fruits of the Holy Ghost

|

|

1. THE FRUIT OF CHARITY

Charity, the first fruit f the Holy Ghost, is, as it were, an overflowing of the theological virtue of Charity. It is by the theological virtue that the soul is united to God. To possess it is to be in the state of grace. It is the indwelling of the Holy Ghost in the soul, and by it we are united to the Three Persons of the Blessed Trinity in a bond of love. A man may have Faith, and yet be without Charity; he does not love God. He may have Faith and Hope, and yet be without Charity. He believes in God, and knows that He rewards the good, and punishes evil. He may hope even that, if he does what God requires of him, he will go to Heaven. But it is only Charity which is the passport to eternal life; and not until he turns away from his sin to God, can the love of God, which is Charity, invade his soul. The operations of the Holy Ghost in the sou,l and personal cooperation therewith, produce an increase of Charity. Love diffuses itself, and mutual love between God and the soul issues in an ever-increasing measure of union. The flame of love burns ever brighter, and its warmth becomes ever more intense. We know how the love of two people, who truly love each other, increases as time goes on. Especially is this true of husband and wife. Nevertheless, it is possible for their love to diminish, and eventually to grow cold. This will only happen through their own fault. People do not fall "out of love" casually, and without reason—an idea popularized to some extent by a parody of romance in fiction and on the screen. True love for another is lost only by an act of the will. Human love, however great it is, however noble and pure, can only be a pale image of the love between God and the soul. God's love cannot change, but the soul's can. By his own fault, a man can refuse the graces offered; he can become less energetic in loving God. He may even turn his will away from God altogether, and forfeit the state of grace by mortal sin. God does not force His love on the soul; He could not, for free will in man requires his willing acceptance and reciprocation. Effect of Charity on the Soul But when God is welcomed in the soul, then there takes place a wonderful surrendering on its part to God's action within it. There is a new access of Charity, which has the effect of conforming the soul to God and uniting it to Him more closely. The Holy Ghost acts on the powers of the soul, which is led to know, love and serve God with greater ardor. The will, cooperating with His grace, conforms more exactly with the will of God; it seeks to do only what God prompts it to do, and every action thus draws the soul to God still more. The union between God and the soul is progressive in those who seek always to please Him. When a person is not far advanced in virtue, then his conformity to the will of God will not be consistent. He may do much that is unpleasmig to God, not from malice but from weakness. As he progresses—and he will progress as long as he is trying, and makes use of the means of grace—he will gradually allow himself more readily to be led by the Holy Ghost. The Holy Ghost acts within the soul; finding it more in conformity with Himself, He can act more freely. In those who want nothing else but His will, there is no hindrance; the will of God is done with the soul's acceptance, by which it cooperates. This conformity with the will of God issues in works of Charity. The union between God and the soul is like the union of husband and wife. It is a union of love, more or less perfect according to the degree of grace arrived at by the soul. just as the union of husband and wife issues in progeny, so does the union of God and the soul. But it is a spiritual progeny; it is a host of good works which are the joint production of God and the soul. Those who begin to love God, are inclined to think that they will henceforth show their love solely by praying much and attending to their spiritual progress. They will need to do that, but progress in the grace of God is never secured by self‑contained spirituality. Just as God has gone out of Himself, as it were, to give Himself to the soul, so must the soul go out of itself to give itself to others. Or rather, this giving of oneself will be the joint work of God and the soul, in the fruit of the Holy Ghost which is Charity. So it is that those advancing in the love of God find joy in doing things for others. And they will learn that they can be doing works of charity all day long, and every day. People often ask: "What work can I take up? What is there for me to do?" But those in whom the Holy Ghost is operating to their progressive sanctification will have no need to ask. They will find that there is plenty for them to do for God in the service of their neighbor from the first thing in the morning to the last thing at night. Charity Expressed in Little Acts They will be little things mostly: helping someone across the road, who is too old, or lame, to cope with the traffic; giving a hand to a blind man in the crowded street; directing someone on his way, or making the tramp feel there is someone who does not despise him. A hundred and one opportunities occur during the day for good acts of all kinds, of help to our neighbor: doing the shopping for someone who is ill in bed; delivering an urgent message, or taking children to school, who would otherwise run risks in the traffic. And if we have to go out and earn our living, there will be numerous kindly offices we can perform in the course of our duties and between whiles. Let no one think lightly of all these little acts, merely because anyone can do them. The Corporal Works of Mercy are held up to us as Christian works of Charity, but, sad to say, they are much neglected nowadays. In a large town, a blind man may be seen tapping his stick on the pavement for help to cross the road, for as long as five minutes together. Meanwhile, people stream by heedless of his helplessness, intent only on their own affairs. Children will stand on the edge of the pavement, eager to cross the road, but afraid, while the traffic rushes by without a break, and regardless of any rights but its own. The general want of kindly considerateness, and realization of duty to others, is eloquent testimony that the love of God is absent. There may, it is true, be acts of kindness from natural motives, so that we are not entitled to say that, whenever Charity seems to be present, it is the fruit of the Holy Ghost. But such kindly acts are frequently casual; if they arise from a mere habit of mind, their motive is not an exalted one. On the other hand, we may be certain that the neglect by so many of the ordinary and everyday works of mercy is a sign that few are attentive to the Holy Ghost—few allow themselves to be guided by Him. Spiritual Works of Mercy Of a higher order are the Spiritual Works of Mercy, and, although the soul which progresses, will at no time neglect the lesser Corporal Works of Mercy, it will mingle more and more of the directly Spiritual Works with them as time goes on. To visit the sick for God's sake, and because the sick person represents the suffering Christ, is an eminent work. But it will be greater still‑‑‑far greater—if its object is to do good to the sick person's soul. It may be someone already advanced in virtue, and then our duty will be done by cheering him, and giving him fresh intentions for his prayers. In that way, we shall be God's instruments in securing for him greater merit still. Or it may be someone who has lapsed from his religious duties, and whom we can help to bring back. It may be some aged invalid; the simple task of reading to him must not be despised. And if it be from some book that has a higher purpose than to be merely entertaining—even though it be not spiritual reading as usually understood—it may have an enormous influence for good on his mind. In visiting the sick, we may be able to tackle members of that large section who profess no religious beliefs at all, or who are groping for some anchor in divine truths. But at all times we should make it our business to bring souls now outside the Fold to a knowledge of the one true Faith. Love of such work is a sure sign of the operation of the Holy Ghost within the soul. For the same Holy Ghost who inspires it is He who lives in the Church. It is the Spirit of Jesus Christ, her Founder. He ever works within her, keeping her from error, and through her bringing to mankind the fruits of the Redemption. It is He who stimulates her growth, offering to souls the world over the means of grace to be secured through membership in the Church. Through the Holy Ghost is finally realized the petition, "Thy Kingdom Come." Zeal for the Cause of Christ Charity is manifested in nothing so much as zeal for the cause of Christ. And His cause is the salvation of souls. But how are we to reconcile this large view with the obvious truth that Charity begins at home? We have all heard of, and perhaps known, the man or woman who gives much time to public duties, and complains that he or she has little time to spare for the home. The family may not be altogether neglected, but it misses something which it ought to have. The energy and zeal which is expended outside might have been used with enormous profit for the benefit of the home. That it ought to have been so used follows from the duty of ministering first to those for whom we are responsible and who are entitled to our care. Children may be old enough to fend for themselves to some extent, but the home remains the chief educative influence, and if the father or mother, elder sisters and brothers are continually absent for the purpose of pursuing less humdrum works of charity than the home gives opportunity for, then the children are losing guidance they ought to have, and solid sustenance the deprivation of which will certainly retard their mental and moral growth. The Right Order of Charity There is a right order in Charity; and the fact that duties may even have to be confined to the home circle, at least for a time, is entirely consistent with the possession of the larger view of Charity which embraces the whole Church and the world. We may look on circles of influence as ever‑widening ones. There is first the home, then the larger unit of the parish, and in secular affairs the whole sphere of professional, business, or occupational life. We may even include recreational activities, as long as they do not encroach on home duties. Sweeping outward, there are diocesan, national, and ultimately world interests. In concentrating on works of Charity nearest to hand‑for most people those to be found in the home and family and in their work—we are not necessarily neglecting the others. The pebble thrown into the pool stays where it pitches. But its influence on the pool at large is demonstrated by the ever‑widening circles which radiate from it. So in the work of charity nearest to hand, we may and should have the intention of profiting larger interests and the Church throughout the world. We may at times be privileged to assist directly in the larger spheres; as long as such assistance does not conflict with our immediate duty, that will be all to the good. But the right order of charity is founded on the fact that we cannot do everything, nor can we be everywhere at once. What we cannot do, the Holy Ghost of God can. While He prompts us to do the work at hand, and helps us to carry it through, He is operating in countless other souls, and in the larger spheres we cannot reach. Because the same Holy Ghost is operating within us, and in other souls at the same time, and because His grace is potent to initiate and direct every good work in the world, we have within us the means by which we ourselves can influence good works far afield. Every Act Can Be a Prayer It is thus that our work for God—and the performance of every duty can come in that category—becomes prayer. But that must not be understood to mean that we may neglect prayer for other works of Charity because they take its place. Prayer is of the essence of the spiritual life. The Holy Ghost inspires prayerful activity. Set times of prayer are given their place in every life lived for God. After a time, prayer becomes more informal, and prayer‑time tends to extend itself throughout the day; ejaculatory prayer becomes the rule at all times, and conversations take place with Our Lord as with our best Friend, who, by His presence within the soul through the Holy Ghost, is with us all the time. Those larger works of Charity in which our duties prevent us from taking part may be the subject of our prayers. By constantly remembering them, we perform better the duties near at hand. We take part in them from the very fact that we take part in the work performed throughout the Church and the world by the Holy Ghost of God. That is a consolation to those who feel that their contribution is inconsequential. Works of Charity are the test of progress in the spiritual life. It is a sham sanctity which spends itself in self‑regard to the neglect of the needs of neighbors. But there are some who can do no more than pray: invalids, for instance, either bedridden, or confined to the house, or a restricted area. These, by their prayers and the offering of their sufferings, may do far more for God and His Church than those who are active. It is to be noted that, when we speak of working for "the Church," we include every good work in the world. The reason is that it is the Church's mission to save souls; and since the salvation of his soul is the ultimate good of every person in the world, all our prayers must tend to secure that end, even though we have not that in mind specifically when we pray. In praying for the world, and everybody in it, we pray for the salvation of souls, which is precisely the Church's work. Invalids perform their works of Charity largely by prayer, which is their contribution towards the vast work of the Church. And it is no light contribution, for it is inspired by the Holy Ghost, and so becomes His work. As St. Paul tells us: "We know not what we should pray for as we ought; but the Spirit Himself asketh for us with unspeakable groanings" (Romans 8:26). Special Merit of Suffering With this goes the offering of sufferings. Suffering itself is prayer when offered to God. And it is prayer of particular potency, for it was through suffering and death that Christ redeemed the world. When a soul is inspired by the Holy Ghost to offer its sufferings for the salvation of the world, it does so in union with the sufferings of Christ on the Cross. Thus does charity overflow in a true imitation of Christ, and a continuation of His work in the world is assured. To be privileged to offer a life of suffering to Almighty God is to be drawn by His Holy Ghost very close to Him. The cumulative sufferings of the world have led to a greater realization by the devout of the usefulness of suffering as a means of obtaining graces for souls from Almighty God. The idea of this work as a true apostolate has given the name of the Apostolate of Suffering to the joint contributions of all those who are willing to offer their pains and inconveniences. But such an apostolate need by no means be confined to the permanent invalid. All have something to suffer, and all may join in this grand work for God's Church. It is another manifestation, and very often the highest, of the operation of the Holy Ghost in the soul. It is a preeminent work of that Charity which is the first fruit of the Holy Ghost. |

|

|

2. THE FRUIT OF JOY

In his book, "All for Jesus," Father Faber says: "Of all the fruits of the Holy Ghost none seems more desirable, because none is less earthly or more heavenly, than joy; and it is just this fruit which Our Blessed Lord bestows on such as devote themselves to intercession. This is very observable. There is a certain sunniness and lightheartedness about them for which there seems no ordinary cause, except that it is like the sweet lightening of the spirit which comes after a kind and unselfish action. This may partly be the reason. But there is another also. We see not the fruit of our intercession; the spirit of prayer escapes out upon the earth, and is everywhere like the hidden omnipresence of God. It is out of our sight. Nay, it is not like a series of distinguishable works. We hardly remember how much intercession we have made. Who can count the sighs he has sent up to God, or the wishes without words which the tongue of his heart has told into the ear of Jesus? So, from the fruit being hidden, vain‑glory attaches to it less than to almost any other devotion. However this may be, sweetness and consolation, submissively desired, are beyond all doubt great helps to holiness; and whosoever desires to joy in God, and to abound in all joy and consolation in the Lord, to be gay and prompt in serving Jesus, to be patient with life because of the desire of death, and to be equable in all things which is not far from being holy in all things, let him throw away himself and his own ends, and, wedding the dear interests of Jesus and of souls, betake himself to intercession, as if it were his trade, or he had as much to do with it as his Guardian Angel has to do with him. Joy is the especial recompense of intercession. It is part of His joy, who rejoices in the harvest of His Passion. What stirs in our hearts has come to us from His. It was first in His, before it was in ours, and an Angel's presence would be less desirable than is that little taste of the Redeemer's Joy." This characteristic passage states in many words what might have been said in a few‑only, however, at the risk of losing the richness of Faber's thought. It impresses on us that joy springs from the doing of works of charity, especially when they are prayerful works. Or we might conclude, both from our own consideration of the matter and from Faber's teaching, that works of charity can only be properly so when they are prayerful. Faber, too, links up joy with the Passion of Our Blessed Lord, thus demonstrating what great joy is in the offering of sufferings in union with Christ. Joy in Unselfishness Faber remarks that there is joy in the unselfishness that sees not the result of its intercession. But, in another sense, the soul has a deeper insight into the results, and that is the cause of its joy as it advances in the love of God. For the result will not be in this or that petition granted; or in seeing this person converted as a result of its prayers, or that one restored to health. Indeed, we can never know exactly how far we ourselves have contributed to the result. We may, for instance, have been praying for a long time for someone to be cured. To our delight, he makes gradual progress, and in the end makes a complete recovery. Our prayers have been heard, but we must not take credit for the cure. We shall hear of other people who have been praying just as we have; each of them is inclined to think that he or she is responsible for having secured the patient's recovery. They may each be surprised that anyone else has had this particular intention so much at heart; they thought they had made it their own. The fact is that the good we have helped to do for any soul is in reality Christ's. It is He who has effected the cure, and it is He who has inspired the prayers through and by the Holy Ghost. It is the same Holy Ghost who prompts the prayer of each and every one of us. The prayer of each is part of one great work, which is really His. No one person can lay claim to having obtained the result, for any power that our prayer has with God is itself from Him. A keener realization of this leads us to see that all our prayer goes into a pool, from which Almighty God can draw to apply it where He sees fit. As we progress in prayer and in the love of the Holy Ghost who is within us, we remark to a greater extent that many of the things we pray for come to pass. They are often things we prayed for long ago; answers to prayer are frequently delayed. But as time goes on, we become less concerned to notice exactly which of our petitions are granted. Often the answers are in different terms from what we expected; but they are answers, just the same. We get to understand that all graces showered down upon the world are in answer to the continual prayer that goes up, and to which we contribute. We rejoice in all the good that is done in the world, and in the overcoming of evil, and we become aware that we share in the fight against evil things in hidden ways as well as more openly. We constantly experience that those nearest to us, as well as we ourselves and others far afield, are receiving spiritual and temporal benefits, and we know that we have been privileged to take our part in obtaining these. Joy in the Holy Ghost Our joy will be in the recognition that the work of the Holy Ghost is succeeding. Bound up with this is the realization that we are being used by Him to further His work. But that involves no selfish congratulation; it is joy in the Holy Ghost, to whom we attribute the success. Joy, the fruit of the Holy Ghost, is a spiritual and supernatural thing. We must not confuse it with a happy "feeling"‑‑‑a delight in the good things of life, and the pleasure of enjoyment. This latter, nevertheless, may be perfectly pure. It may even be linked up with holy joy. It may be an overflowing of the joy of soul which is from the Holy Ghost, so as to embrace all the gifts of God in a perpetual song of thanksgiving. It is thus that the Saints have enjoyed the good things of life. They come to enjoy what is meant to be enjoyed, not from the motive of pleasureseeking, but because they are so full of the Holy Ghost of God that they are able to receive His gifts in the proper proportion. Their pleasure in things is rooted in their love of God. Thus, the joyous St. Francis in his "Canticle of the Sun" praises God for all His various gifts, and as we read this marvellous poem we detect that his delight in God's creation exceeds anything that the worldly can imagine. Whereas those whose thoughts and aims are kept on earthly things seek a "good time" in pleasure alone, the Saint finds exquisite enjoyment in the things that God provides, because, through the indwelling of the Holy Ghost and progress in the spiritual life, he has become thoroughly attuned to the Spirit of Christ. His enjoyment of things partakes of the perfection with which the God‑Man enjoyed them. There is no longer any selfseeking, and so selfish pleasure is excluded. So, we find St. Francis rejoicing in every one of God's creatures. He singles out for mention Brother Sun: all created things are his brothers and sisters, because he, like them, is from the hand of God, and he has been created a man only by the good pleasure of God, and has nothing in his own right to boast of that is superior to them. Then there is Sister Moon, Brother Wind and Air; clouds, and weather‑‑‑"be it dark or fair." He praises Sister Water, Brother Fire, Mother Earth: Who governs and sustains us; who gives birth To all the many fruits and herbs that be; And colored flowers in rich variety. Then he praises God for persons "who pardon wrong for love of Thee," and for those who endure sorrow for a long time, "bearing their woes in peace." He ends with the praise of Sister Death "from whom no living soul escapes." He rejoices for those who die in the grace of God. True and Spurious Joy A man could enjoy life as St. Francis did only because he rejoiced in God and not in self. Such enjoyment is the fruit of the Holy Ghost, and is far removed from what the world falsely thinks is enjoyment. The worldly do not know that their pleasures are merely on the surface; that they never get beyond the sugar coating, and know nothing of the substance underneath. Were they to know of the deep joys of the Holy Ghost, they would want to cast aside the spurious imitation which they themselves are only too aware never satisfies them, and take measures to secure what the Saints valued, even though this would mean great sacrifice and a long period of preparation. They would be like the man in the Biblical parable who sold all he had in order to buy the field in which was buried the hidden treasure. If the joy which is the fruit of the Holy Ghost must not be confused with surface delights, it must also not be confused with surface feelings which good people often enjoy. These again may be perfectly good when they overflow from the interior joy which the Holy Ghost bestows. But they are not joy in themselves. They are certainly from God, and therefore a grace, and are often given to beginners as an encouragement to devotion. After Holy Communion the soul may experience an access of what it thinks to be fervor, but true fervor is in the will, and the joyful feeling is intended as a spur to the love of God. The soul will be misled if it becomes attached to the feeling of devotion so as to aim at experiencing it again. That is very like pleasure‑seeking. Almighty God has a way of withdrawing such feelings in order to test whether the soul is sincere. If it is merely the pleasures of devotion that a person wants, then he will slacken in his efforts to advance in the love of God as soon as he enjoys them no longer. But if it is God Himself who is the object of his love and desires, then he will continue in devotion and service, however hard that may become. Joy of God's Presence Superficial feelings of devotion may be withdrawn sooner than they otherwise would have been, if the soul makes them too much the object of its desire. But again we must not confuse these with the deeper joy of God's presence, which is desirable in itself. The soul advancing in the love of God suffers many deprivations, but all the time the Holy Ghost who dwells within it is producing a closer and closer union of the soul with the Three Divine Persons. God's presence in the soul is something that may be experienced, or it may not. It makes itself felt in differing degrees, and there are all kinds of distractions in life which keep us from paying due attention to it. When a person is troubled about many things, or unduly busy through no fault of his own, there is not the same keenness of perception of the divine presence that there may be in quieter seasons. Nevertheless, the most advanced souls can remain in the presence of God even when engaged in a multitude of duties. It is said of St. Francis de Sales that, in spite of the busy life which he was bound to live, he never lost the realization of the presence of God in his soul. That is no doubt true also of other Saints who have led busy lives in the world, except when for a time God has seen fit to withdraw it for their good, and their further advancement in grace. The soul, having once experienced the joy of God's presence, earnestly desires to possess it again when it has been withdrawn. It is right that the soul should desire it, because it is a wonderful help towards zeal in His service. It is of a different order from those surface feelings allowed to beginners. They are apt to be sought for their own sake, whereas the joy of the spiritually mature is bound up with the desire to be active in God's service. Moreover, the desire for the joy of God's presence is not a vain sighing for the pleasurable. It prompts the soul to remove the obstacles which might keep the Holy Ghost from revealing Himself more. The soul which has this desire will examine the cause of its distractions, and make every effort to ensure that their occasion is avoided. The devout are accustomed to place themselves in the presence of God before they pray or meditate. For those who would advance it will be the aim to be so habitually in the presence of God that prayer finds its proper atmosphere at all times. Joy in Its Fullest Fruition The joy which is the fruit of the Holy Ghost ultimately becomes so deep that nothing in the world can disturb it. That is joy in its full fruition, the joy of the Saints. It exists even in times of suffering. That sounds foolishness to the world, and is an enigma to many good people. But since we know that it was through suffering that Christ redeemed the world, and that the sufferings of men in union with His serve to make reparation for sin, we cannot escape the conclusion that suffering is powerful to advance the cause of Christ. But the Saint is aware that his sufferings are his share in the Passion of Christ. He knows that, whatever he himself may suffer, the work for God that results from the offering of his suffering is in reality Christ's work. It is a work, moreover, that is effected in and through the Holy Ghost. The Saint rejoices that his suffering can do good, and the joy that is his is highest in suffering because suffering itself goes so much against the grain. For that reason, too, the greatest graces are earned for souls through suffering. The Saint, even though he may have much to bear, does not attribute to himself the resultant graces that are bestowed upon the world. He knows the work to be Christ's, effected through the Holy Ghost who dwells within him. The Saint's joy in suffering is joy in the Holy Ghost. He comes to long for suffering because thereby God's work in the world is advanced enormously. He has long ago ceased to regard self, but his enjoyment is none the less because of that. He may indeed be said to be the only man who has the joy of living, and that is because his joy is wholly from the Holy Ghost, and has no inferior taint whatsoever. |

|

3. THE FRUIT OF PEACE

There is nothing the world misunderstands so much as Christian peace. It is the complaint of the Church's critics that, although she has been in existence for nearly two thousand years, she has not yet persuaded nations to live at peace with one another. The trend, they point out, is all the other way. War is perpetually threatened as the solution for international disputes; and as the years go on, wars, when they come, are more violent and widespread than ever before in history. The critics regard the Church as a kind of society for the prevention of war, when actually she professes to be nothing of the kind. She lays down no injunction against further wars, though she condemns modem barbaric methods of warfare. The critics overlook that her Divine Founder proclaimed that He came not to give peace but a sword. And yet He was the Prince of Peace. How do we explain that? Conditions for a Just War The answer is that peace is secured through fighting evil things. It may be the duty of a nation to make a stand against injustice. She may secure a spurious peace by refusing to do so, but it will prove to be an uneasy peace, which is in reality no peace at all. Doubtless, a nation ill‑equipped to fight will find peace by giving way to greater force, for she will be doing injustice to her subjects if she involves them in a hopeless fight. But, even for her, peace will not be obtained by ready acquiescence. Her duty lies, and her hope for peace, only by issuing the strongest protest against the evil will of her enemy, for silence means acceptance. The appearance of peace is no guarantee of peace in fact. We have become used to that long preparation for war which is in reality all part of war itself. When the spirit of hatred inspires dealings between nations, then there is a kind of war even in peacetime. This warlike spirit makes itself felt within nations as well as between them. The constant injustice that prevails in internal affairs, whether they be political, commercial, or private, is a form of warfare; it is peaceful only because it does not use the acknowledged instruments of war. Peace and Toleration of Injustice People who fail to fight injustice, through cowardice or because they are on the side of the unjust, can never be at peace. A man may accept an unjust bargain, he may acquiesce in being victimized, or calmly suffer persecution, if he only is concerned. In this he has the example for all time of Our Blessed Lord Himself. But he may not acquiesce in injustice in the sense that he approves of it. It is his duty, moreover, positively to fight it, or to protest against it if the perpetrators are too strong to be opposed, whenever the injustice is directed against others, and he is in a position to defend them. This principle provides the sanction for nations in war. Rulers have a duty to their subjects; they must protect them against aggression and any attack on their rights. Often a man will do well to oppose injustice directed against himself, or to fight it, even when there is no apparent positive duty of protecting the rights of others. We often hear people say that they are not so much concerned to defend their own rights when acting in this way, but do so "on principle." When sincere, this is a very laudable motive, for in standing up for himself against tyranny a man is standing up for all who may have to suffer the same things. He is not only giving others who may have cloudy notions on principles of right and wrong an insight into the truth, but by his opposition he is putting the brake on the activities of the unjust. By thwarting the unjust in this instance, he may incapacitate them for further activities of the kind. True peace is not secured by giving way through mere spinelessness. A superficial peace may result from taking the line of least resistance, but peace which is the fruit of the Holy Ghost is a peace of soul which comes about only through having made all just causes one's own. The whole Christian life is a warfare, a battle against the devil and his angels. Without the spirit of opposition to all that God opposes, the Christian cannot claim to be serving the cause of Christ. Peace is only obtained at the cost of warfare. Seen thus, a new light is thrown on the words of Our Lord: "I came not to give peace, but a sword." Peace is truly in the soul. A man may be involved deeply in affairs which are litigious or warlike, and yet be at peace. The peace of God is wholly interior. "I am a man of peace, therefore I am relishing a fight," said a devout man. That was not contradictory, because his fight was in a just cause, and he was aware that he would never have peace of mind if he refused the challenge. The false peace engendered by the devil is ever an unquiet one, for, if he accepts it, a man in greater or less degree assents to the false maxims of the devil. These can only make for disturbance of soul, since it is only by pursuing the path of virtue that the mind is at ease. Peace the Fruit of a Good Conscience Peace is, therefore, fundamentally the fruit of a good conscience. It will be greater or less, in proportion to the degree of advancement of the soul in the love of God. All in the state of grace will have it, but it can only be perfect in those who have conformed their will to the will of God to such an extent that they have no longer any affection for what is sinful or imperfect. In the truly peaceful soul there is perfect balance, so that no happenings, however adverse, can really disturb it. It is possible perhaps to lose peace of mind for a time, without losing the peace of a good conscience. It is then that the sense of peace is somewhat obscured. This happens to scrupulous souls, and those who have given way too much to anxiety. It may be a particular trial sent by Almighty God in order to lead the soul to greater heights of virtue. It is usually an indication that the soul is not yet so far advanced that it can keep a quiet mind at all times and in all circumstances. But if the soul persists in fostering scruples or anxiety, it may well be that its advance will be hindered. Peace is secured only by resignation to God's will and a firm trust in the guidance of the Holy Ghost. Peace comes from the Gift of Understanding, which enables the soul to see what a tremendous thing it is to possess God and His sanctifying grace in the soul. Conflict Usually Precedes True Peace In considering loss of peace of mind, we have another example of the truth that true peace is only secured by strife. It is the devil's object to distract us as much as he can from attention to the Holy Ghost who dwells within us. If he can do that successfully, he is well on the way to tempting us to sin. Our protection against sin is remembrance of God. And if we become accustomed to treating with Him as the Guest within our souls, we shall find little attraction in unlawful pleasures. If, then, the devil can produce a distraction within the soul, as he does when he introduces disturbing trains of thought, he has already set up a rivalry in our minds between the thought of God and other things. To take every suitable measure to counteract the things which make for loss of peace of mind is, therefore, part of the general campaign for securing that peace which is the fruit of the Holy Ghost. It is still a fight against evil things, and the guidance of our spiritual director will be invaluable for showing us the proper means to take. With progress in the spiritual life, a deep peace will underlie even the agitation which often we are unable to control because of our sensitiveness to outward troubles. But we shall learn that this is only on the surface, like the ripples which seem to disturb the pool, while underneath all is calm. The mind which is truly at peace is disturbed by nothing. The indwelling of the Holy Ghost ensures a calm that cannot be taken away except by mortal sin, for only that can drive Him out. His presence indicates that peace is a positive reality; it is not just a negative thing, such as is secured by an unwillingness to be in the fray, or inability to take up arms, or even being placed in circumstances which keep one out of the conflict. Peace is not just absence of war; it is itself a virile and vigorous thing. It does not inspire a person to hide himself away in a corner, so as to avoid any trouble that he may meet in the crowded thoroughfare. The contemplative monk or nun who seeks solitude does not do so because he or she wants to escape the combat. Their fight, as ours, is against evil things; theirs is fought 'in the spiritual realm and is for that reason harder, because in those regions there are not the tangible supports which give us at least something to lean upon and handle. Action in God's Cause Leads to Peace Peace impels to action in God's cause: for the contemplative it will be spiritual action; for others it is both spiritual and the more direct activity in the busy world. At first it may seem strange that peace, which is secured by struggle, should again prompt to still further action. We might have thought that peace would imply a settled state of the soul, as if it were now at rest. In a sense it is; it is no longer troubled by the things that formerly made for loss of peace. The indwelling of the Holy Ghost has a stabilizing effect, so that it can now gather its powers for far greater efforts in God's service than ever before. Peace of soul, the fruit of the Holy Ghost, is a source of strength. Good works done by the man of peace have a distinguishing character. There is about them none of that uncertainty and experimental taint, which vitiates much of the work of men who have not the glory of God in view. There is a certain directness, an unwavering aim, in the good works of the peaceful man. That is because he has himself in hand, or rather is in the hands of God. The Holy Ghost can make better use of one who has conquered himself, than one who, in attempting the main battle against God's enemies, is distracted by private quarrels. To have arrived at perfect peace is to have won the fight against self, and he, who has done that, is now ready for carrying on the larger warfare in Christ's interests. Discord Sometimes Invades Good Works How often do we find that an unquiet spirit invades work done for God in private or parish life! That is because the enemy of souls has been allowed to intrude his poison into minds. It is he who inspires folk to mix selfish motives with work genuinely intended at first to be done for God's sake. Personal ambition becomes too strong, and the desire to win credit for personal efforts, comes to outweigh the wish to serve God. That does not mean that those, who introduce discord, are necessarily devoid of sanctifying grace. Sometimes they may be, and then the work is unfortunate for having their help, in so far as the right motive may be lacking in them. But generally, motives will be mixed in proportion to the degree of the love of God to which each has attained. The man who wholly loves God, without any admixture of self‑love, will be so powerful an instrument in God's hands, that any work he takes up for God will be wholly God's. The Holy Ghost, who dwells within him, will meet with no obstacle when He inspires the soul to good works, and His inspiration will be continuous also because of that. It will be less fruitful in those who are less advanced. Fundamentally, because they possess God, they will wish to please Him. But self still has a place in their esteem, their aim is divided, and, consequently, much of their effort is misplaced. Works for God often suffer from the fact that God is not the entire object of them. God is a jealous God, and His service demands that the whole man be engaged in it. What should we think of the sculptor who, in undertaking to produce a sculpture of someone, should allow his attention to be diverted by making the work an advertisement of himself, so that, although it was still in some degree a likeness of the sitter, it introduced for all to see features that belonged to the artist? That is only a weak metaphor of what happens when people seek self in their work for God. For where there is not singleness of purpose in good works, disharmony is bound to enter. That arises from the fact that the spirit of God is one of peace; introduce into your intention anything other than the purpose of pleasing God, and you introduce a discordant element. We may also liken the perfect work to a pure song of praise. The imperfect has an ugly sound, from which it is difficult to disentangle the right sequence. Work done for God is orderly, and perfect in rhythm; it is the overflow from a peaceful soul. When done by many in combination, it is like the prayer of praise that goes up from minds perfectly attuned to each other. And they are attuned to each other because each is at tuned to the spirit of God which inspires the whole work. Disharmony Mars Peace of World The lack of peace in the world is the sign that the Holy Ghost of God is not allowed to inspire the world's work. He is absent too often from men's souls, and so there is disharmony in what they do—disharmony first in their own souls, and then between them and their fellow‑men. There can be no peace where God is left out of account. If He be not in men to direct them, all they do will be marred by the continual conflict which must be taking place within them: not the rightful conflict which issues in peace, but that in which the devil conquers either way—a conflict which is never resolved, so that the soul is always tormented by disquiet. Make no mistake, our public men, who make today so great a show of confidence, and who pretend to have the solution of world problems discovered by their own powers, are profoundly unhappy men. They are never at peace, for they ignore, in their lives and activities, the only Source of peace, the Holy Ghost of God, who alone can inspire the things that are to the peace of the world. Spirit of Christ the Spirit of Peace How necessary it is for men to have peace in their own hearts is shown from the fact that Our Lord was always instilling it. "Peace be to you," was His salutation, and the Church takes up the cry of her Master. "The peace of the Lord be always with you," the priest says at every Mass. "Peace be to you" has been the salutation of the Franciscan Friars the world over, and through the centuries; it is the greeting also, full of consolation, and bringing a grace of its own, of many other priests. "Pax" (peace) is the motto of the Benedictine Order. The spirit of peace is the breath of Christ. "Peace I leave with you," He said, "My peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, do I give unto you." There He explains how this true peace differs from that which the world pretends to give. The world's so‑called peace is spurious. "Do this; do that," it says, "and we will leave you in peace." "Cast a grain of incense into the incense-bowl to the worship of a false god, and we will leave you in peace to worship your God." "Deny one very small article of your Faith, and we will leave you free to practise your religion for the rest of your life." Peace indeed! For the sake of this pretended peace, the soul is to suffer the tortures of a conscience defied. Better to suffer death, and ensure "the peace of God which surpasseth all understanding" (Philippians 4:7). Peace is only from God; the world cannot give it. For peace is an interior thing, which even the martyrs roasted over a slow fire, or the victims in the arena, can possess. It is they, perhaps, who know more fully than any what true peace is, because all their thoughts and energies are caught up in the energizing and peaceful Spirit of God, who is within them. Though they may be afflicted outwardly, the affliction is too outward to disturb the deep‑seated peace, that has resulted from the soul's victory in the conflict, which has decided who shall reign within it. The peace of such souls, the fruit of the Holy Ghost, is a promise of the eternal peace that shall be theirs in Heaven. |

|

4. THE FRUIT OF PATIENCE

If we observe any representative section of the community (for instance, the passengers in a bus), we might conclude from their demeanor that the average citizen is a model of patience. There is a kind of calm that speaks of contentment and good nature. But bring into the gathering a disturbing influence‑perhaps a conductor who fails to temper his zeal with tact in demanding obedience to some traffic ordinance, or an unreasonable passenger who expects privilege rather than strict rights, and is insulting into the bargain! Forthwith we shall find that in the parties immediately concerned in the dispute there is generally a loss of the calm they seemed to possess. They are impatient, and unwilling to consider the other person's point of view. And this impatience tends to spread to all who takes sides in the dispute. All are unwilling to examine the other side of the question; and when there is clear evidence of fault on their side, they have not the patience to consider it. Superficial Calm Is Not Patience From this, when it happens, we cannot help concluding that the calm we thought was there was only on the surface. The patience that we thought was deep‑seated was easily ruffled, so that we doubt whether it was really patience at all. But in proposing a public conveyance as the scene of our survey, we mean only to give an example. What is true of the public conveyance is paralleled wherever people make social contacts. The lack of patience is displayed most in places and situations in which there is no need to keep up a pretense of civility; it is nowhere so evident as in the home. It used to be said that there was no place like home. That was true when its ideal was Nazareth, and the home was recognized as the place where the Christian virtues were to be fostered. But the desire to acquire and inculcate these virtues has waned with the progressive disregard for religion. The home is no longer a center for the cultivation of the fruits of the Holy Ghost, for He, for the most part, has been banished. Patience, particularly appropriate in home life, is no longer deemed to be essential, when the family is not recognized as the fundamental unit of society. Cultivation of Patience in the Home The cultivation of patience would keep the home together; a contempt for it ministers to its disruption. And so we have, amongst other evils, the break‑up of homes by separation and divorce, a menace that continues to increase in alarming proportion. The slightest disagreement, the smallest ground for annoyance, is put forward as a pretext for dissolving the partnership. Sometimes the decision to part is so hurried that it is repented of soon afterwards. It is not unknown for divorced husband and wife to "re‑marry" after they have been released by the law of the land. Impatience is so habitual that it takes control of the situation, which is the same as saying that the devil takes control. What we see in private life is a reflection of what is happening in world affairs. Nations will take hold of any supposed failing in another nation, and use it as the pretext of a quarrel. They will see their own interests threatened in moves which have no real hostile intent, and will scom the patient 'inquiry which might have put them in their proper light. The famous phrase, "My patience is exhausted," is used to justify what cannot be justified, for true patience is never exhausted. There may be departures from patience in those who have not fully acquired it, but, where the Spirit of God is present, it will return. The soul in which the Holy Ghost dwells has within it the Source of patience, so that it has an inexhaustible fund on which to draw. Patience Is a Rare Virtue Today But, sad to say, the display of patience in circumstances which try it is exceptional. Patience is a rare virtue, because the Holy Ghost of God is not allowed to reign in the souls of men. And it may be noted that even the outward show of patience is sometimes nothing more than a national trait. Southern peoples do not always appear to be so patient, because they are naturally more animated. And yet there may be more real patience underneath the surface. The display or otherwise of the virtue may be according to national temperament. It will be affected also by personal temperament. There is a patience which is natural, and not inspired by the indwelling of the Holy Ghost. But even that is desirable as a basis on which He can build. Such patience is shown in the refusal to lose one's temper. But true patience, the kind that is the fruit of the Holy Ghost, is not just the refusal to lose one's temper. Just as peace is a positive and virile thing, so is patience. It is not something that is only brought into play when outward circumstances demand its exercise, but is a vivifying influence at all times. Its supernatural character may be gauged from the fact that it is essentially interior, and operates in processes which take place within the soul. Patience with Self and with Others There is a patience with oneself as well as a patience with others. We cannot imagine the man whose whole ambition is centered in worldly things being patient with himself. On the contrary, it is a feature of the really worldly that they are bent on success, and impatient of anything that may impede it; they do not admit within themselves the possibility of not being able to reach their goal. They have a confidence, often unwarranted, in their own ability, and fume and chafe at any obstacles in the way of demonstrating it. True patience is, first of all, a patience in acquiring virtue; it must be exercised that the soul may progress. "To be patient with self," says Father Faber (in his book "'Growth in Holiness."), "is an almost incalculable blessing, and the shortest road to improvement, as well as the quickest means by which an interior spirit can be formed within us, short of that immediate touch of God which makes some souls interior all at once. It breeds considerateness and softness of manner towards others. It disinclines us to censoriousness, because of the abiding sense of our own imperfections. It quickens our perception of utterest dependence on God and grace, and produces at the same time evenness of temper and equality of spirits, because it is at once an effort, and yet a quiet sustained effort. It is a constant source of acts of the most genuine humility. In a word, by it we act upon self from without, as if we were not self, but self's master, or self's guardian angel. When this is done in the exterior life as well as the interior, what remais in order to perfection?" What a large fund of patience is needed in our relations with others! And how well this is acquired by those who have trained themselves to be patient with self in spiritual advancement! The interior training precedes the outward exercise of the virtue. That gives the reason why good works are more perfectly performed by those advanced in the spiritual life. The demands on patience in work for souls are tremendous, and can be properly met only by those who are equipped to meet them. Patience with Fellow‑Workers Patience is needed with fellow‑workers. The numerous occasions of friction through disagreement on method, or failure to see problems in the same light, require patience in a high degree. There should never be opposition in matter of principle in works of charity, but sad experience shows that too often there is. Frequently, one has a greater insight into what is principle than another, and then the situation calls for a particular measure of patience. It is difficult to have to correct those who act in perfectly good faith and according to their lights, but the Holy Ghost who inspires souls to exercise patience gives also the graces which will make such exercise fruitful. He can always be relied upon to sustain the soul in the exercise of any virtue, when there is a pure intention of doing only His will and of not being diverted from duty. We have to remember, too, that the same Holy Ghost who guides and sustains the perfect dwells also in the less perfect, provided they have not rejected Him by mortal sin. He who inspires the perfect to act inspires also the less perfect, and it will often happen that they are led to accept the advice of those of their fellow‑workers who are spiritually competent to give it. Patience is exercised by tact, and sometimes the sensitive suffer from the sense of being ignored or over‑ridden. The grace of God will smooth out ruffled feelings, and patience shown by one will have its effect in inculcating patience in others. Patience Needed in Work for Christ Immense patience is needed also in our dealings with those who are the object of our works of charity. How easy it is to become impatient with the poor, the improvident, the foolish, and sinful! We may at times be justly angry, as was Our Lord when He drove the money changers out of the Temple. But such anger will normally be directed against those that exploit persons whom we feel it our obligation to protect‑‑‑not against those who need our protection and help, however shiftless and irresponsible they may be. Just anger, moreover, is not a thing we should too lightly presume to have. Only those who are so far advanced in the spiritual life as to have themselves under perfect control may safely be angry in God's interests, and then only they whom He inspires to be so. In our performance of works of charity to others, perhaps the feature that will most try our patience is their want of gratitude. Beginners in such works are apt to think they will be overwhelmed with the thanks of those to whom they do favors. But ingratitude seems to be the rule; often it is mere thoughtlessness or forgetfulness, but it is difficult to bear until the soul has learned to look to God only for thanks‑‑‑and He bestows them by greater graces. Christ's Patience with the Ungrateful Gratitude when shown is a beautiful thing, all the more so because it is so rare. We are at least in the highest company in suffering through lack of it. Did not Our Lord deplore that, out of ten lepers whom He cured, only one returned to thank Him? The poor and unfortunate are apt to look upon favors received by them as received by right. It is true that the better‑off have an obligation to help them, but what the recipients of charity often overlook is that those who actually do help them are often not much better‑off than themselves; that frequently those who give do so at great personal sacrifice. But the faults of the less fortunate must be borne with as much patience as those of others with whom we live or come into contact. Some relationships demand an heroic patience, as when a particularly trying person has to be lived with. An example occurs in the Life of the Curé of Ars, who for eight long years had to bear with a conceited and overbearing curate, apparently "sent by God to try His servant's patience." Probably a similar trial was borne by St. Thomas More in his second marriage, for by all accounts his second wife was a most trying person. But both these people, the Curé of Ars' curate and St. Thomas More's second wife, were estimable folk; their fundamental goodness doubtless made the trial all the greater, for it must have often made them appear to have right on their side. To have borne with their eccentric behavior and constant complaints and criticism needed an equanimity which could only come from a continuous and courageous reliance on the support of the Holy Ghost of God. How God Trains Us in Patience God's ways of working exercise our patience. What long years we have to wait for answers to our prayers! In what suspense He often keeps us before our aspirations are satisfied! How, for long periods at a time, He seems to hide Himself, so that we hardly know whether we are in His favor or not! But He never tries us longer than we can bear. Just when we think we are beginning to find the trial of our patience too much, He shows us in one way or another that it has not been for nothing; He encourages us to go on serving Him. In all this He has our spiritual advancement in view. To those who He sees will reach a high degree of virtue He sends longer and more severe trials of patience. A writer has shown how Pope Benedict XV persevered in his efforts to secure peace in the first World War, in spite of continual disappointment and frustration. He regards this as an example of heroic exercise of the virtue of hope, which inspired the continuation of patient effort in God's cause. The soul which has God's glory only in view will persevere in any work that the Holy Ghost has inspired it to do, knowing that it must eventually succeed in some way, and is all the time succeeding in a hidden if not obvious way, for the furthering of Christ's cause. Practice of Patience in Afflictions To persevere in effort even though the results are not visible, is a form of patience in suffering. But perhaps the hardest kind of patience is that of one who suffers intense pain, or who is prevented by sickness from following an active life. Here is missing the interest in external things which serves to distract the sufferer who plods on in spite of no tangible result. The invalid's life tends to be sheer monotony, especially when there is loss of use of limbs or faculty. The life of such a sufferer calls for patience of a high order. That it is the fruit of the Holy Ghost in those who offer their sufferings for the salvation of the world is guarantee that their offering is accepted. Such souls, and all who exercise patience for God's sake, share in the patience of Christ in His Passion. They share also in the patience of the Holy Ghost with men. When we consider the vast number of men and women who spurn Him altogether, and again the large proportion of the others who heed Him very little, we can only marvel at the infinite patience of God with His creatures. It is that on which we must model ourselves; it is made manifest for us in the patience of Our Lord with men when He lived and suffered on earth. We share God's patience, because we have Him dwelling within us. It is for us to reproduce it in our dealings with other people. We have to bear with the sins of the world, as He does. And that, not only for our own sanctification, but also that we may be His instruments in the world's reformation. |

|

|

5. THE FRUIT OF BENIGNITY