| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

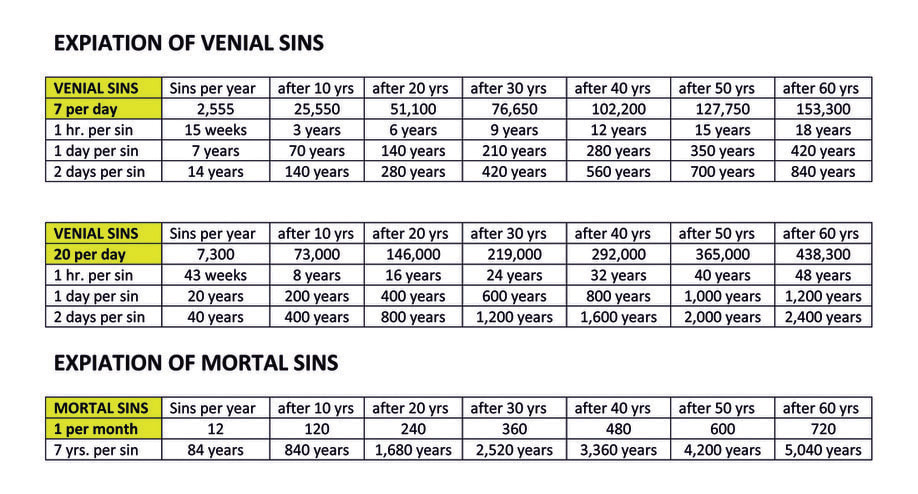

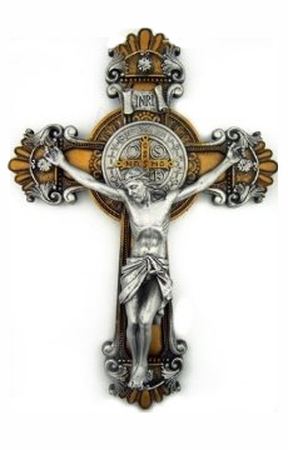

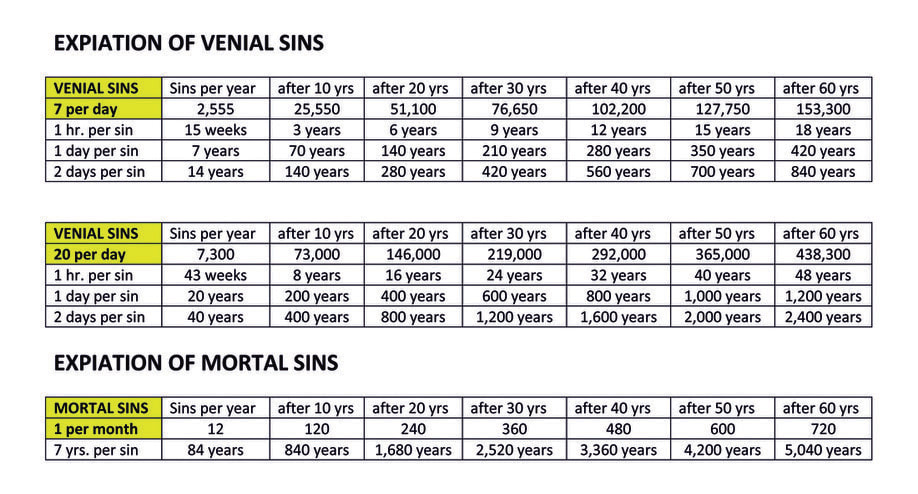

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

DAILY THOUGHTS FOR ADVENT

Tuesday December 24th

The Vigil of Christmas

Article 18

One Day to Go! Three Keys to Heaven ― The Third Key: Charity

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

The Vigil of Christmas

Article 18

One Day to Go! Three Keys to Heaven ― The Third Key: Charity

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

The King of the Castle―The Peak of the Mountain

Holy Scripture―whether it be Our Lord speaking, or the Apostles or Prophets―paints an awesome towering powerful picture of the virtue of Charity. Founded on Faith, driven by Hope―Charity is the fiery force that drives all virtues. It is life-giving soul to all virtues. It is the fuel that drives them. Without it―all is nothing. If you find that hard to believe, then simply read the words of Scripture.

First of all, you smacked right between the eyes by the simple yet profound fact that “God is charity!” (1 John 4:8). Scripture doesn’t say “God is Faith” or “God is Hope”, but it says that “God is Charity”! Therefore, God must hate all that is “not Charity.” Already in the Old Testament, we God command: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole strength” (Deuteronomy 6:5). In the New Testament, Our Lord―Who is God Himself in the flesh―tells us that Charity or Love is the greatest and first among Commandments:

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole mind, and with thy whole strength. This is the first commandment! And the second is like to it: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. There is no other commandment greater than these!” (Mark 12:30-31).

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind: and thy neighbor as thyself!” (Luke 10:27).

“Jesus said to him: ‘Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole mind! This is the greatest and the first commandment. And the second is like to this: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments dependeth the whole law and the prophets.’” (Matthew 22:37-40).

Without Charity We Are Nothing

Our Lord and God told us: “Without Me, you can do nothing!” (John 15:5). Since “God is Charity”, it logically follows that “Without Me (that is to say, Charity), you can do nothing!” Pretty logical, huh? St. Paul agrees and drives that point home powerfully: “If I speak with the tongues of men, and of angels, and have not Charity―then I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And if I should have prophecy and should know all mysteries, and all knowledge, and if I should have all Faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not Charity―then I am nothing. And if I should distribute all my goods to feed the poor, and if I should deliver my body to be burned, and have not Charity―then it profiteth me nothing!” (1 Corinthians 13:1-3).

Holy Scripture―whether it be Our Lord speaking, or the Apostles or Prophets―paints an awesome towering powerful picture of the virtue of Charity. Founded on Faith, driven by Hope―Charity is the fiery force that drives all virtues. It is life-giving soul to all virtues. It is the fuel that drives them. Without it―all is nothing. If you find that hard to believe, then simply read the words of Scripture.

First of all, you smacked right between the eyes by the simple yet profound fact that “God is charity!” (1 John 4:8). Scripture doesn’t say “God is Faith” or “God is Hope”, but it says that “God is Charity”! Therefore, God must hate all that is “not Charity.” Already in the Old Testament, we God command: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole strength” (Deuteronomy 6:5). In the New Testament, Our Lord―Who is God Himself in the flesh―tells us that Charity or Love is the greatest and first among Commandments:

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole mind, and with thy whole strength. This is the first commandment! And the second is like to it: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. There is no other commandment greater than these!” (Mark 12:30-31).

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind: and thy neighbor as thyself!” (Luke 10:27).

“Jesus said to him: ‘Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart, and with thy whole soul, and with thy whole mind! This is the greatest and the first commandment. And the second is like to this: Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. On these two commandments dependeth the whole law and the prophets.’” (Matthew 22:37-40).

Without Charity We Are Nothing

Our Lord and God told us: “Without Me, you can do nothing!” (John 15:5). Since “God is Charity”, it logically follows that “Without Me (that is to say, Charity), you can do nothing!” Pretty logical, huh? St. Paul agrees and drives that point home powerfully: “If I speak with the tongues of men, and of angels, and have not Charity―then I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And if I should have prophecy and should know all mysteries, and all knowledge, and if I should have all Faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not Charity―then I am nothing. And if I should distribute all my goods to feed the poor, and if I should deliver my body to be burned, and have not Charity―then it profiteth me nothing!” (1 Corinthians 13:1-3).

Monday December 23rd

Article 17

Two Days to Go! Three Keys to Heaven ― The Second Key: Hope

Article 17

Two Days to Go! Three Keys to Heaven ― The Second Key: Hope

Anchored in Hope

In the Western artistic tradition the symbol of Hope has been the anchor, the saving instrument of ships tossed around by the winds and waves on a stormy sea. When sailors throw the anchor and it grabs the solid sea floor below, it promises safety to the endangered crew.

More than the anchor itself, the simple event of its being thrown and its stabilizing effect on the ship is a fair image of the working of Hope. As fragile beings, we are tossed around by the winds and waves of the present. We need and want stability, and we find it by tying ourselves through the bond of hope to some future event. And through hope, we can find stability and meaning in our stormy present.

Mary is Our Anchor of Hope

Let us reflect upon these beautiful words of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, from his homily on the feast of the Holy Name of Mary (September 12th):

“And the Virgin’s name was Mary.” Let us speak a little about this name, which is said to mean “star of the sea,” and which so well befits the Virgin Mother. Rightly is she likened to a star. As a star emits a ray without being dimmed, so the Virgin brought forth her Son without receiving any injury. The ray takes naught from the brightness of the star, nor the Son from His Mother’s virginal integrity. This is the noble star risen out of Jacob, whose ray illumines the whole world, whose splendor shines in the heavens, penetrates the abyss, and, traversing the whole earth, gives warmth rather to souls than to bodies, cherishing virtues, withering vices. Mary is that bright and incomparable star, whom we need to see raised above this vast sea, shining by her merits, and giving us light by her example.

“All of you, who see yourselves amid the tides of the world, tossed by storms and tempests rather than walking on the land, do not turn your eyes away from this shining star, unless you want to be overwhelmed by the hurricane. If temptation storms, or you fall upon the rocks of tribulation, look to the star: Call upon Mary! If you are tossed by the waves of pride or ambition, detraction or envy, look to the star, call upon Mary. If anger or avarice or the desires of the flesh dash against the ship of your soul, turn your eyes to Mary. If troubled by the enormity of your crimes, ashamed of your guilty conscience, terrified by dread of the judgment, you begin to sink into the gulf of sadness or the abyss of despair, think of Mary. In dangers, in anguish, in doubt, think of Mary, call upon Mary. Let her name be even on your lips, ever in your heart; and the better to obtain the help of her prayers, imitate the example of her life:

“Following her, thou strayest not; invoking her, thou despairest not; thinking of her, thou wanderest not; upheld by her, thou fallest not; shielded by her, thou fearest not; guided by her, thou growest not weary; favored by her, thou reachest the goal. And thus dost thou experience in thyself how good is that saying: ‘And the Virgin’s name was Mary.’”

Our Lady a Source of Faith, Hope and Charity

In Our Lady, we find a resource for strengthening all three theological virtues. The following quote is taken from one of the readings in the Masses of Our Lady, which shows that Mary's love for us is the sum and soul of her powerful intercession for us with Christ. Hence, absolute trust in Mary's help is a necessary part of the virtue of hope. “I am the mother of fair love, and of fear, and of knowledge, and of holy hope. In me is all grace of the way and of the truth; in me is all hope of life and of virtue” (Ecclesiasticus. 24:24-25). That short passage is extremely deep and broad. “I am the mother of fair love, and of fear, and of knowledge, and of holy hope” manifests all the three theological virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity. “I am the mother of fair love [Charity], and of fear, and of knowledge [Faith], and of holy hope [Hope].

Fr. Faber Encourages a Great Hope in Our Lady

Similarly to St. Bernard, Fr. Frederick Faber encourages us to a greater Faith in Mary, a stronger Hope of Mary and deeper Love of Mary. “One man has been striving for years [HOPING] to overcome a particular fault, and has not succeeded. Another mourns, and almost wonders while he mourns, that so few of his relations and friends have been converted to the Faith [HOPE]. One grieves that he has not devotion enough; another that he has a cross to carry which is a peculiarly impossible cross to him [HOPE FOR HELP]; while a third has domestic troubles and family unhappiness which feel almost incompatible with his salvation [HOPE]; and for all these things prayer [HOPE] appears to bring so little remedy.

“But what is the remedy that is wanted? What is the remedy indicated by God Himself? If we may rely on the disclosures of the saints, it is an immense increase of devotion to [LOVE OF] our Blessed Lady; but, remember, nothing short of an immense one [IMMENSE LOVE]. Mary is not half enough preached [FAITH=KNOWLEDGE]. Devotion to [LOVE OF] her is low and thin and poor. It is always invoking human respect and carnal prudence, wishing to make Mary so little of a Mary that Protestants may feel at ease about her. Its ignorance of theology [LACK OF FAITH=KNOWLEDGE] makes it unsubstantial and unworthy. It is not the prominent characteristic of our religion which it ought to be. It has no Faith [HOPE] in itself. Hence it is that Jesus is not loved [LOVE], that heretics are not converted [FAITH & HOPE], that the Church is not exalted; that souls which might be saints wither and dwindle [NO LOVE]; that the Sacraments are not rightly frequented [NO LOVE], or souls enthusiastically evangelized [FAITH].

“Jesus is obscured because Mary is kept in the background [FAITH NOT TAUGHT]. Thousands of souls perish because Mary is withheld from them [FAITH NOT TAUGHT]. It is the miserable, unworthy shadow which we call our devotion to [LOVE OF] the Blessed Virgin that is the cause of all these wants and blights, these evils and omissions and declines. Yet, if we are to believe the revelations of the saints, God is pressing for a greater, a wider, a stronger, quite another devotion to [LOVE OF] His Blessed Mother. I cannot think of a higher work or a broader vocation for anyone than the simple spreading of [THE FAITH] this peculiar devotion of St. Louis Grignon de Montfort. Let a man but try it for himself, and his surprise at the graces it brings with it, and the transformations it causes in his soul, will soon convince him of its otherwise almost incredible efficacy as a means for the salvation of men, and for the coming of the kingdom of Christ. Oh, if Mary were but known [FAITH], there would be no coldness [LACK OF LOVE] to Jesus then! Oh, if Mary were but known [FAITH], how much more wonderful would be our Faith.” (Fr. Frederick Faber, Preface to True Devotion to Mary).

Hoping Now and Hoping for the Future

Hope here is to be thought of, not only as looking forward to Heaven―which will be granted us if we do our part in this life―but also and more especially, as having confidence in the power of God to straighten out our muddled lives, even now while we are still living. The first meaning, of this theological virtue, is certainly pointed toward the everlasting happiness that will fulfill the promises of Christ, but there is a nearer meaning of it, that looks to God’s Providence from day to day. It is this second sort of Hope that sanctity develops and brings to perfection. As part of this Hope that deveops and prefects our sanctity here below―God has chosen Mary and ruled that all His graces will pass through her hands. In that sense, we Hope in God through Mary and we expect God to respond to our Hope by helping us through Mary.

For instance, the clause “Thy kingdom come,” in the Our Father, expresses the long-distance Hope, whereas the clause “Give us this day our daily bread” expresses the local or immediate Hope. Likewise the words of the Hail Mary: “Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death”―the words “Pray for us sinners now” express an immediate Hope that focuses on the “here and now”; whereas the words “…and at the hour of death” express the long-distance Hope, which focuses on our future death. Sanctity touches both, but one of its more immediate effects is to enlarge the virtue of trust: the conviction that God is giving us our daily bread, and will go on doing so. It is a side of Hope that is very close to Faith, and, for this reason, it makes the same demands upon us as Faith does: perseverance and prayer and the single eye that looks below the surface for the things of God and refuses the worldly view. If “the just man lives by Faith” (Habacuc 2:4; Romans 1:17; Galatians 3:11), and if Charity is both the “bond” (Colossians 3:14) of the just man’s perfection and the “urge” (2 Corinthians 5:14) that sets him to work upon his perfection, then Hope is his greatest support. Most of our difficulties and failures come because we too easily lose heart.

Hope Faces and Accepts Difficulty and Mistakes

Now, Hope starts off by knowing that life is going to be difficult. It admits that―without grace―perfection is miles out of reach. It faces the idea of failure. It sees how there are bound to be disappointments and temptations all along the line. But Hope just goes right on trusting. A person who is strong in this kind of Hope, looks upon everything that comes along — even mistakes and serious failures — as being a chance not to be missed. Instead of sinking into a mood of despair and self-pity, such a person says simply: “This has turned out wrong, and everything is in a mess, and I have no idea how it is going to be put right―but I can still count absolutely on the Providence of God.”

You can readily see how, if we are to be saints, we shall need Hope at every step. Perhaps the most important stage, in a soul’s journey toward perfection, is the stage when a soul realizes that the whole of life lies in the hollow of God’s hand. From that point onward the soul can look at all the happenings, that take place, as one who looks down at them from a height―he is seeing them from God’s angle. So he never lets himself get upset; he is always ready for the next thing; he is never surprised at his own blunders. He refuses to worry about his own point of view, because he is far more concerned with God’s.

God Knows―You Don’t Need to Know

God is the only person who knows how your well you are praying or how your holiness is progressing―so why fuss and worry? God is the only person who can judge what sort of a character you really have―so why look into yourself so often and get discouraged and put on an act? God is the only person who can tell how far you have gotten in the journey toward Him―so why try to measure the distance and put in little flags to show that you are making the grade? Leave all that to God — in trust. It is not easy to do this―but then Faith and Hope are not easy virtues to practice in their perfection, and it is Faith and Hope that are the surest sign that the soul possesses Charity.

One of the chief differences between the saints and ourselves is that when things go wrong (and they never go absolutely right for very long), the saints take it for granted that God is treating them lovingly and wisely; we, on the other hand, jump at once to the conclusion that God, either does not mind what happens to us, or is handing out a punishment. Sanctity always gives God the benefit of the doubt. In fact, it gives Him the benefit of a certainty: He cannot go wrong―He has a plan and He never stops loving.

Stop Bleating and Trust the Shepherd

Remember how Our Lord spoke of Himself as the Good Shepherd (John 10:11-16, 26-28). Try to see what this means. Forget about the pretty pictures of Jesus rescuing sweet little lambs, and just think for a minute what goes on in the mind of a shepherd who is good. Such a shepherd will want the best for his flock―whatever happens. If he has to lead his sheep over rough ground, it is only so that they may have better grass to feed on. If he steers them away from shrubs they want to nibble, it is only because he knows what plants are bad for them. If he allows them to stay out in the rain, it is only because they will get weak and flabby, unless they spend more time out in the open, than around a comfortable fire sheltered from the winds.

Go from thinking what is in the mind of a shepherd, who is good, to imagining what is in the mind of a sheep, who is good. Everyone knows that sheep are great at following. The better the sheep, the more ready it is to take the lead of the shepherd. In other words, the good sheep trusts. When the shepherd takes an unexpected path, the sheep tags on and does not question the direction. When the shepherd whistles for the sheepdog and sends it to round up the strays, there are no complaints about cruelty and about the horrible barking and about how much nicer the other dog was, before this one came along. Good sheep accept all these things as part of the business of being sheep. Still more, they accept them as part of the business of following a shepherd they trust.

True Hope Fosters True Courage

You can see, from what has been said above, that Faith leads to Hope and sanctity leads to courage. A person has to have great courage if he is to turn away from his own ideas about safety and trust himself to somebody else’s―even if that somebody else is God. That “trust” in God is Hope. But you have to understand that this courage is not the kind that is called “daring”. To be daring may be far more fun, and we admire the dashing hero, when we see him in a movie―but courage is far more pleasing to God. Daring may be no more than boldness, the exciting instinct that takes risks―whereas courage is a deliberately built-up state of mind. The saints are not daredevils, plunging about and lunging in and out because they love danger; they are cool and calm men and women, who go on and on serving God―because it is their duty to do so. This slow kind of courage is sheer virtue, and is all the more valuable to God, because it is so little noticed by human beings.

The saints are ready enough to take risks when the occasions come up — such as when they serve lepers, or expose themselves to persecution and martyrdom for the sake of spreading the Faith — but this is always because they take such risks in their stride, as being part of their service of God, and not because they see them as something glamorous. The saints are ready to become fools for Christ’s sake (1 Corinthians 4:10), but they do not have to be foolhardy. It is not that they want to make a name for themselves — either as heroes or as saints — but that they want to put God’s interests first―and they are prepared to go to any lengths to see that God’s interests are served.

Therefore, you could say that Faith enlightens the soul by informing it that God desires its holiness. Hope then―realizing that human power cannot achieve this―turns to God and hopes and trusts that God will help it progress in holiness. St. Louis de Montfort, in his book The Secret of Mary, enlightens us about our calling or vocation and presents to our Hope the means by which we can attain our calling:

“Chosen soul, living image of God and redeemed by the Precious Blood of Jesus Christ, God wants you to become holy like Him in this life, and glorious like Him in the next (Matthew 5:48). It is certain that growth in the holiness of God is your vocation. All your thoughts, words, actions, everything you suffer or undertake, must lead you towards that end. Otherwise you are resisting God, in not doing the work for which He created you and for which He is even now keeping you in being. What a marvelous transformation is possible! Dust into light, uncleanness into purity, sinfulness into holiness, creature into Creator, man into God! A marvelous work, I repeat, so difficult in itself, and even impossible for a mere creature to bring about, for only God can accomplish it by giving His grace abundantly and in an extraordinary manner. The very creation of the universe is not as great an achievement as this.

“Chosen soul, how will you bring this about? What steps will you take to reach the high level to which God is calling you? The means of holiness and salvation are known to everybody, since they are found in the Gospel; the masters of the spiritual life have explained them; the saints have practiced them and shown how essential they are for those who wish to be saved and attain perfection. These means are: sincere humility, unceasing prayer, complete self-denial, abandonment to divine Providence, and obedience to the will of God. The grace and help of God are absolutely necessary for us to practice all these, but we are sure that grace will be given to all, though not in the same measure. I say ‘not in the same measure,’ because God does not give His graces in equal measure to everyone (Romans 12:6), although, in His infinite goodness, He always gives sufficient grace to each soul. A person who corresponds to great graces performs great works, and one who corresponds to lesser graces performs lesser works. The value and high standard of our actions corresponds to the value and perfection of the grace given by God and responded to by the faithful soul. No one can contest these principles.” (St. Louis de Montfort, The Secret of Mary).

The Nativity of Our Hopeful Sanctity

St. Louis continues: “It all comes down to this, then. We must discover a simple means to obtain from God the grace needed to become holy. It is precisely this I wish to teach you. My contention is that you must first discover Mary if you would obtain this grace from God. Mary alone found grace with God for herself and for every individual person (Luke 1:30). No patriarch nor prophet nor any other holy person of the Old Law could manage to find this grace. It was Mary who gave existence and life to the author of all grace and, because of this, she is called the “Mother of Grace.” God the Father, from Whom, as from its essential source, every perfect gift and every grace come down to us (James 1:17), gave her every grace when He gave her His Son. Thus, as St. Bernard says, the will of God is manifested to her in Jesus and with Jesus. God chose her to be the treasurer, the administrator and the dispenser of all His graces, so that all His graces and gifts pass through her hands. Such is the power that she has received from Him that, according to St. Bernardine, she gives the graces of the eternal Father, the virtues of Jesus Christ, and the gifts of the Holy Ghost to whom she wills, as and when she wills, and as much as she wills. As in the natural life a child must have a father and a mother, so in the supernatural life of grace a true child of the Church must have God for his Father and Mary for his mother. If he prides himself on having God for his Father, but does not give Mary the tender affection of a true child, he is an imposter and his father is the devil.

“Since Mary produced the head of the elect, Jesus Christ, she must also produce the members of that head, that is, all true Christians. A mother does not conceive a head without members, nor members without a head. If anyone, then, wishes to become a member of Jesus Christ, and consequently be filled with grace and truth, (John 1:14), he must be formed in Mary through the grace of Jesus Christ, which she possesses with a fullness enabling her to communicate it abundantly to true members of Jesus Christ, her true children. The Holy Ghost espoused Mary and produced His greatest work, the incarnate Word, in her, by her and through her. He has never disowned her and so He continues to produce every day, in a mysterious but very real manner, the souls of the elect in her and through her” (St. Louis de Montfort, The Secret of Mary).

In the Western artistic tradition the symbol of Hope has been the anchor, the saving instrument of ships tossed around by the winds and waves on a stormy sea. When sailors throw the anchor and it grabs the solid sea floor below, it promises safety to the endangered crew.

More than the anchor itself, the simple event of its being thrown and its stabilizing effect on the ship is a fair image of the working of Hope. As fragile beings, we are tossed around by the winds and waves of the present. We need and want stability, and we find it by tying ourselves through the bond of hope to some future event. And through hope, we can find stability and meaning in our stormy present.

Mary is Our Anchor of Hope

Let us reflect upon these beautiful words of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, from his homily on the feast of the Holy Name of Mary (September 12th):

“And the Virgin’s name was Mary.” Let us speak a little about this name, which is said to mean “star of the sea,” and which so well befits the Virgin Mother. Rightly is she likened to a star. As a star emits a ray without being dimmed, so the Virgin brought forth her Son without receiving any injury. The ray takes naught from the brightness of the star, nor the Son from His Mother’s virginal integrity. This is the noble star risen out of Jacob, whose ray illumines the whole world, whose splendor shines in the heavens, penetrates the abyss, and, traversing the whole earth, gives warmth rather to souls than to bodies, cherishing virtues, withering vices. Mary is that bright and incomparable star, whom we need to see raised above this vast sea, shining by her merits, and giving us light by her example.

“All of you, who see yourselves amid the tides of the world, tossed by storms and tempests rather than walking on the land, do not turn your eyes away from this shining star, unless you want to be overwhelmed by the hurricane. If temptation storms, or you fall upon the rocks of tribulation, look to the star: Call upon Mary! If you are tossed by the waves of pride or ambition, detraction or envy, look to the star, call upon Mary. If anger or avarice or the desires of the flesh dash against the ship of your soul, turn your eyes to Mary. If troubled by the enormity of your crimes, ashamed of your guilty conscience, terrified by dread of the judgment, you begin to sink into the gulf of sadness or the abyss of despair, think of Mary. In dangers, in anguish, in doubt, think of Mary, call upon Mary. Let her name be even on your lips, ever in your heart; and the better to obtain the help of her prayers, imitate the example of her life:

“Following her, thou strayest not; invoking her, thou despairest not; thinking of her, thou wanderest not; upheld by her, thou fallest not; shielded by her, thou fearest not; guided by her, thou growest not weary; favored by her, thou reachest the goal. And thus dost thou experience in thyself how good is that saying: ‘And the Virgin’s name was Mary.’”

Our Lady a Source of Faith, Hope and Charity

In Our Lady, we find a resource for strengthening all three theological virtues. The following quote is taken from one of the readings in the Masses of Our Lady, which shows that Mary's love for us is the sum and soul of her powerful intercession for us with Christ. Hence, absolute trust in Mary's help is a necessary part of the virtue of hope. “I am the mother of fair love, and of fear, and of knowledge, and of holy hope. In me is all grace of the way and of the truth; in me is all hope of life and of virtue” (Ecclesiasticus. 24:24-25). That short passage is extremely deep and broad. “I am the mother of fair love, and of fear, and of knowledge, and of holy hope” manifests all the three theological virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity. “I am the mother of fair love [Charity], and of fear, and of knowledge [Faith], and of holy hope [Hope].

Fr. Faber Encourages a Great Hope in Our Lady

Similarly to St. Bernard, Fr. Frederick Faber encourages us to a greater Faith in Mary, a stronger Hope of Mary and deeper Love of Mary. “One man has been striving for years [HOPING] to overcome a particular fault, and has not succeeded. Another mourns, and almost wonders while he mourns, that so few of his relations and friends have been converted to the Faith [HOPE]. One grieves that he has not devotion enough; another that he has a cross to carry which is a peculiarly impossible cross to him [HOPE FOR HELP]; while a third has domestic troubles and family unhappiness which feel almost incompatible with his salvation [HOPE]; and for all these things prayer [HOPE] appears to bring so little remedy.

“But what is the remedy that is wanted? What is the remedy indicated by God Himself? If we may rely on the disclosures of the saints, it is an immense increase of devotion to [LOVE OF] our Blessed Lady; but, remember, nothing short of an immense one [IMMENSE LOVE]. Mary is not half enough preached [FAITH=KNOWLEDGE]. Devotion to [LOVE OF] her is low and thin and poor. It is always invoking human respect and carnal prudence, wishing to make Mary so little of a Mary that Protestants may feel at ease about her. Its ignorance of theology [LACK OF FAITH=KNOWLEDGE] makes it unsubstantial and unworthy. It is not the prominent characteristic of our religion which it ought to be. It has no Faith [HOPE] in itself. Hence it is that Jesus is not loved [LOVE], that heretics are not converted [FAITH & HOPE], that the Church is not exalted; that souls which might be saints wither and dwindle [NO LOVE]; that the Sacraments are not rightly frequented [NO LOVE], or souls enthusiastically evangelized [FAITH].

“Jesus is obscured because Mary is kept in the background [FAITH NOT TAUGHT]. Thousands of souls perish because Mary is withheld from them [FAITH NOT TAUGHT]. It is the miserable, unworthy shadow which we call our devotion to [LOVE OF] the Blessed Virgin that is the cause of all these wants and blights, these evils and omissions and declines. Yet, if we are to believe the revelations of the saints, God is pressing for a greater, a wider, a stronger, quite another devotion to [LOVE OF] His Blessed Mother. I cannot think of a higher work or a broader vocation for anyone than the simple spreading of [THE FAITH] this peculiar devotion of St. Louis Grignon de Montfort. Let a man but try it for himself, and his surprise at the graces it brings with it, and the transformations it causes in his soul, will soon convince him of its otherwise almost incredible efficacy as a means for the salvation of men, and for the coming of the kingdom of Christ. Oh, if Mary were but known [FAITH], there would be no coldness [LACK OF LOVE] to Jesus then! Oh, if Mary were but known [FAITH], how much more wonderful would be our Faith.” (Fr. Frederick Faber, Preface to True Devotion to Mary).

Hoping Now and Hoping for the Future

Hope here is to be thought of, not only as looking forward to Heaven―which will be granted us if we do our part in this life―but also and more especially, as having confidence in the power of God to straighten out our muddled lives, even now while we are still living. The first meaning, of this theological virtue, is certainly pointed toward the everlasting happiness that will fulfill the promises of Christ, but there is a nearer meaning of it, that looks to God’s Providence from day to day. It is this second sort of Hope that sanctity develops and brings to perfection. As part of this Hope that deveops and prefects our sanctity here below―God has chosen Mary and ruled that all His graces will pass through her hands. In that sense, we Hope in God through Mary and we expect God to respond to our Hope by helping us through Mary.

For instance, the clause “Thy kingdom come,” in the Our Father, expresses the long-distance Hope, whereas the clause “Give us this day our daily bread” expresses the local or immediate Hope. Likewise the words of the Hail Mary: “Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death”―the words “Pray for us sinners now” express an immediate Hope that focuses on the “here and now”; whereas the words “…and at the hour of death” express the long-distance Hope, which focuses on our future death. Sanctity touches both, but one of its more immediate effects is to enlarge the virtue of trust: the conviction that God is giving us our daily bread, and will go on doing so. It is a side of Hope that is very close to Faith, and, for this reason, it makes the same demands upon us as Faith does: perseverance and prayer and the single eye that looks below the surface for the things of God and refuses the worldly view. If “the just man lives by Faith” (Habacuc 2:4; Romans 1:17; Galatians 3:11), and if Charity is both the “bond” (Colossians 3:14) of the just man’s perfection and the “urge” (2 Corinthians 5:14) that sets him to work upon his perfection, then Hope is his greatest support. Most of our difficulties and failures come because we too easily lose heart.

Hope Faces and Accepts Difficulty and Mistakes

Now, Hope starts off by knowing that life is going to be difficult. It admits that―without grace―perfection is miles out of reach. It faces the idea of failure. It sees how there are bound to be disappointments and temptations all along the line. But Hope just goes right on trusting. A person who is strong in this kind of Hope, looks upon everything that comes along — even mistakes and serious failures — as being a chance not to be missed. Instead of sinking into a mood of despair and self-pity, such a person says simply: “This has turned out wrong, and everything is in a mess, and I have no idea how it is going to be put right―but I can still count absolutely on the Providence of God.”

You can readily see how, if we are to be saints, we shall need Hope at every step. Perhaps the most important stage, in a soul’s journey toward perfection, is the stage when a soul realizes that the whole of life lies in the hollow of God’s hand. From that point onward the soul can look at all the happenings, that take place, as one who looks down at them from a height―he is seeing them from God’s angle. So he never lets himself get upset; he is always ready for the next thing; he is never surprised at his own blunders. He refuses to worry about his own point of view, because he is far more concerned with God’s.

God Knows―You Don’t Need to Know

God is the only person who knows how your well you are praying or how your holiness is progressing―so why fuss and worry? God is the only person who can judge what sort of a character you really have―so why look into yourself so often and get discouraged and put on an act? God is the only person who can tell how far you have gotten in the journey toward Him―so why try to measure the distance and put in little flags to show that you are making the grade? Leave all that to God — in trust. It is not easy to do this―but then Faith and Hope are not easy virtues to practice in their perfection, and it is Faith and Hope that are the surest sign that the soul possesses Charity.

One of the chief differences between the saints and ourselves is that when things go wrong (and they never go absolutely right for very long), the saints take it for granted that God is treating them lovingly and wisely; we, on the other hand, jump at once to the conclusion that God, either does not mind what happens to us, or is handing out a punishment. Sanctity always gives God the benefit of the doubt. In fact, it gives Him the benefit of a certainty: He cannot go wrong―He has a plan and He never stops loving.

Stop Bleating and Trust the Shepherd

Remember how Our Lord spoke of Himself as the Good Shepherd (John 10:11-16, 26-28). Try to see what this means. Forget about the pretty pictures of Jesus rescuing sweet little lambs, and just think for a minute what goes on in the mind of a shepherd who is good. Such a shepherd will want the best for his flock―whatever happens. If he has to lead his sheep over rough ground, it is only so that they may have better grass to feed on. If he steers them away from shrubs they want to nibble, it is only because he knows what plants are bad for them. If he allows them to stay out in the rain, it is only because they will get weak and flabby, unless they spend more time out in the open, than around a comfortable fire sheltered from the winds.

Go from thinking what is in the mind of a shepherd, who is good, to imagining what is in the mind of a sheep, who is good. Everyone knows that sheep are great at following. The better the sheep, the more ready it is to take the lead of the shepherd. In other words, the good sheep trusts. When the shepherd takes an unexpected path, the sheep tags on and does not question the direction. When the shepherd whistles for the sheepdog and sends it to round up the strays, there are no complaints about cruelty and about the horrible barking and about how much nicer the other dog was, before this one came along. Good sheep accept all these things as part of the business of being sheep. Still more, they accept them as part of the business of following a shepherd they trust.

True Hope Fosters True Courage

You can see, from what has been said above, that Faith leads to Hope and sanctity leads to courage. A person has to have great courage if he is to turn away from his own ideas about safety and trust himself to somebody else’s―even if that somebody else is God. That “trust” in God is Hope. But you have to understand that this courage is not the kind that is called “daring”. To be daring may be far more fun, and we admire the dashing hero, when we see him in a movie―but courage is far more pleasing to God. Daring may be no more than boldness, the exciting instinct that takes risks―whereas courage is a deliberately built-up state of mind. The saints are not daredevils, plunging about and lunging in and out because they love danger; they are cool and calm men and women, who go on and on serving God―because it is their duty to do so. This slow kind of courage is sheer virtue, and is all the more valuable to God, because it is so little noticed by human beings.

The saints are ready enough to take risks when the occasions come up — such as when they serve lepers, or expose themselves to persecution and martyrdom for the sake of spreading the Faith — but this is always because they take such risks in their stride, as being part of their service of God, and not because they see them as something glamorous. The saints are ready to become fools for Christ’s sake (1 Corinthians 4:10), but they do not have to be foolhardy. It is not that they want to make a name for themselves — either as heroes or as saints — but that they want to put God’s interests first―and they are prepared to go to any lengths to see that God’s interests are served.

Therefore, you could say that Faith enlightens the soul by informing it that God desires its holiness. Hope then―realizing that human power cannot achieve this―turns to God and hopes and trusts that God will help it progress in holiness. St. Louis de Montfort, in his book The Secret of Mary, enlightens us about our calling or vocation and presents to our Hope the means by which we can attain our calling:

“Chosen soul, living image of God and redeemed by the Precious Blood of Jesus Christ, God wants you to become holy like Him in this life, and glorious like Him in the next (Matthew 5:48). It is certain that growth in the holiness of God is your vocation. All your thoughts, words, actions, everything you suffer or undertake, must lead you towards that end. Otherwise you are resisting God, in not doing the work for which He created you and for which He is even now keeping you in being. What a marvelous transformation is possible! Dust into light, uncleanness into purity, sinfulness into holiness, creature into Creator, man into God! A marvelous work, I repeat, so difficult in itself, and even impossible for a mere creature to bring about, for only God can accomplish it by giving His grace abundantly and in an extraordinary manner. The very creation of the universe is not as great an achievement as this.

“Chosen soul, how will you bring this about? What steps will you take to reach the high level to which God is calling you? The means of holiness and salvation are known to everybody, since they are found in the Gospel; the masters of the spiritual life have explained them; the saints have practiced them and shown how essential they are for those who wish to be saved and attain perfection. These means are: sincere humility, unceasing prayer, complete self-denial, abandonment to divine Providence, and obedience to the will of God. The grace and help of God are absolutely necessary for us to practice all these, but we are sure that grace will be given to all, though not in the same measure. I say ‘not in the same measure,’ because God does not give His graces in equal measure to everyone (Romans 12:6), although, in His infinite goodness, He always gives sufficient grace to each soul. A person who corresponds to great graces performs great works, and one who corresponds to lesser graces performs lesser works. The value and high standard of our actions corresponds to the value and perfection of the grace given by God and responded to by the faithful soul. No one can contest these principles.” (St. Louis de Montfort, The Secret of Mary).

The Nativity of Our Hopeful Sanctity

St. Louis continues: “It all comes down to this, then. We must discover a simple means to obtain from God the grace needed to become holy. It is precisely this I wish to teach you. My contention is that you must first discover Mary if you would obtain this grace from God. Mary alone found grace with God for herself and for every individual person (Luke 1:30). No patriarch nor prophet nor any other holy person of the Old Law could manage to find this grace. It was Mary who gave existence and life to the author of all grace and, because of this, she is called the “Mother of Grace.” God the Father, from Whom, as from its essential source, every perfect gift and every grace come down to us (James 1:17), gave her every grace when He gave her His Son. Thus, as St. Bernard says, the will of God is manifested to her in Jesus and with Jesus. God chose her to be the treasurer, the administrator and the dispenser of all His graces, so that all His graces and gifts pass through her hands. Such is the power that she has received from Him that, according to St. Bernardine, she gives the graces of the eternal Father, the virtues of Jesus Christ, and the gifts of the Holy Ghost to whom she wills, as and when she wills, and as much as she wills. As in the natural life a child must have a father and a mother, so in the supernatural life of grace a true child of the Church must have God for his Father and Mary for his mother. If he prides himself on having God for his Father, but does not give Mary the tender affection of a true child, he is an imposter and his father is the devil.

“Since Mary produced the head of the elect, Jesus Christ, she must also produce the members of that head, that is, all true Christians. A mother does not conceive a head without members, nor members without a head. If anyone, then, wishes to become a member of Jesus Christ, and consequently be filled with grace and truth, (John 1:14), he must be formed in Mary through the grace of Jesus Christ, which she possesses with a fullness enabling her to communicate it abundantly to true members of Jesus Christ, her true children. The Holy Ghost espoused Mary and produced His greatest work, the incarnate Word, in her, by her and through her. He has never disowned her and so He continues to produce every day, in a mysterious but very real manner, the souls of the elect in her and through her” (St. Louis de Montfort, The Secret of Mary).

Sunday December 22nd

Article 16

Three Days to Go! Three Keys to Heaven ― The First Key: Faith

Article 16

Three Days to Go! Three Keys to Heaven ― The First Key: Faith

Don’t You Wish You Had a Key to Heaven?

Who wouldn’t like to be given a key to Heaven! What a gift! Priceless! Out of this world! Worth giving your life for! Yet―believe it or not―God has not only given you a key to Heaven, but He has given you THREE keys to Heaven! “Faith, Hope, and Charity, these three” (1 Corinthians 13:13).

Before we embark on the examination of the first of these three keys―the key of Faith―let us listen to (without falling asleep) to the preciseness of St. Thomas Aquinas on these three keys―or three “Theological Virtues” as they called. Though it might be a little boring (in places) to read, such precision is extremely important in these days of “wishy-washiness” and sentimental emotional thinking. One of reasons that the Church in general, and each member of the clergy and laity in particular, find themselves in this mess of a Crisis of Faith and Morals that we are living through, is the sad fact that most people have ceased to think, reason, judge and act in a logical way. Instead, they think, reason, judge and act according to their feelings, emotions, impressions and imagination. Logic is guided and fueled by careful study and breadth of knowledge. Feelings, emotions, impressions and imagination need no study or breadth of knowledge―they just “shoot from the hip” or “shoot from the lip” by speaking out and acting out without thinking things out―because they no longer know how to think correctly and therefore they fail to act correctly. “The tongue of the wise adorns knowledge―but the mouth of fools bubbles out folly” (Proverbs 15:2). “The heart of the wise seeks instruction and the mouth of fools feeds on foolishness” (Proverbs 15:14). “The heart of fools is in their mouth: and the mouth of wise men is in their heart” (Ecclesiasticus 21:29). “The words of the mouth of a wise man are grace: but the lips of a fool shall throw him down headlong” (Ecclesiastes 10:12).

St. Thomas on the “Three Keys”

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica (IIa-IIae, q. 62), writes: “the Divine Law contains precepts about the acts of faith, hope, and charity: for it is written (Ecclesiasticus 2:8, seqq.): ‘Ye that fear the Lord believe Him,’ and again, ‘hope in Him,’ and again, ‘love Him.’ Therefore Faith, Hope, and Charity are virtues directing us to God. Therefore they are theological virtues. The theological virtues direct man to supernatural happiness … Man’s happiness is twofold … One happiness is proportionate to human nature, a happiness which man can obtain by means of his natural principles. The other is a [supernatural] happiness surpassing man’s nature, and which man can obtain by the power of God alone … And because such [supernatural] happiness surpasses the capacity of human nature, man’s natural principles, which enable him to act well according to his human capacity, do not suffice to direct man to this [supernatural] happiness. Hence it is necessary for man to receive from God some additional principles, whereby he may be directed to supernatural happiness … Such principles are called ‘theological virtues’―first, because their object is God, inasmuch as they direct us in the correct and proper way to God; secondly, because they are infused in us by God alone; thirdly, because these virtues are not made known to us, except by Divine revelation, contained in Holy Scripture.” (St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIa-IIae, q. 62, art. 1).

“The object of the theological virtues is God Himself, Who is the last end of all … These virtues are called Divine … because, through them, God makes us virtuous and directs us to Himself. The reason and will are naturally directed to God … But the reason and will are not sufficiently directed to Him in so far as He is the object of supernatural happiness … They fall short of the order of supernatural happiness, according to 1 Corinthians 2:9: ‘The eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither hath it entered into the heart of man, what things God hath prepared for them that love Him.’ Consequently, man needed to receive, in addition, something supernatural to direct him to a supernatural end. First, as regards the intellect, man receives certain supernatural principles, which are held by means of a Divine light―these are the articles of Faith, about which is Faith. Secondly, the will of man is directed to this supernatural end as something attainable—and this relates to Hope—and, as to a certain spiritual union [with God], whereby the will is, so to speak, transformed by that [supernatural] end—and this belongs to Charity.” (St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIa-IIae, q. 62, art. 2 & 3).

“It is by Faith that the intellect sees the object of Hope and Love [that object is God]. Hence in the order of generation, Faith precedes Hope and Charity. In a similar manner, a man loves a thing because he sees it as his good. Now from the very fact that a man hopes to be able to obtain some good through someone, he looks on the man, in whom he hopes, as a good of his own. Hence, for the very reason that when a man hopes in someone, he proceeds to love him. So in the order of generation, Hope precedes Charity. But in the order of perfection [the degree of perfection of each virtue], Charity precedes Faith and Hope―because both Faith and Hope are quickened by Charity, and receive from Charity their full complement as virtues. In this way Charity is the mother and the root of all the virtues.” (St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, IIa-IIae, q. 62, art. 4).

As an addendum to what St. Thomas explains, it can be said that we cannot hope in anything or love anything unless we FIRST KNOW of its existence―that is the role of Faith. It is through Faith that we know about God. The more we know, then the more we will hope and love. This truth is behind St. Thérèse of Lisieux’s comment that Jesus is so little loved because He is so little known. You cannot love what you do not know. You will not seek what you do not know. Knowing is NOT ENOUGH―it is merely theory. Theory must be put into practice in some way―it must be used―knowledge or theory is a seed that must be planted, watered and nourished so that can sprout and grow into something more than just knowledge or theory. Knowledge or theory must lead to a Hope of acquiring or achieving what is known. Without that Hope, no action will be taken―for any action will be seen as hopeless and therefore pointless. That Hope drives us on through all obstacles to obtain what we KNOW and LOVE. The love that sprouts from knowledge is merely an IMPERFECT LOVE―because we have not yet attained what we KNOW about and what we desire or LOVE. St. Thomas Aquinas says that one of the elements of love is a UNION of wills―therefore, if we cannot be united to what we love, then that love is imperfect, unrequited, unfulfilled. Union is a necessary completion or perfection for LOVE―and HOPE drives us on and on until we achieve that union.

A second addendum―which is very important for our modern society where “knowledge is power”―is the fact that Faith (knowledge) alone will not save us. It is the blossoming or sprouting of that Faith into Hope and finally Charity that will save us―as the following Scriptural quotes prove: “Faith, if it have not works, is dead in itself. But some man will say: ‘Thou hast Faith, and I have works!’ Show me thy Faith without works―and I will show thee, by works, my Faith! Thou believest that there is one God. Thou dost well, but the devils also believe and tremble. Wilt thou know, O vain man, that Faith without works is dead? … For even as the body without the spirit is dead; so also Faith without works is dead!” (James 2:17-26).

Another quote―that builds upon the previous one―tells us that “any old” works are not enough, but that any works that we do, must be done out of Charity, that is to say, out of a love of God and for God’s sake: “If I speak with the tongues of men, and of angels, and have not Charity―then I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal. And if I should have prophecy and should know all mysteries, and all knowledge, and if I should have all Faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not Charity―then I am nothing. And if I should distribute all my goods to feed the poor, and if I should deliver my body to be burned, and have not Charity―then it profiteth me nothing!” (1 Corinthians 13:1-3).

We could easily paraphrase the above passage and apply it our Christmas preparations: “If I should have the most beautiful Christmas nativity scene or tallest Christmas tree in the neighborhood, but have not charity (a love of God and His Word), then I am nothing! If I should have the most brilliant display of Christmas lights that anyone has ever seen, but have not charity (a love of God and His Word), then I am nothing! If should prepare the most sumptuous Christmas dinner that anyone has ever tasted, but have not charity (a love of God and His Word), then I am nothing! If I should buy and distribute to others the best Christmas gifts they have ever received, but have not charity (a love of God and His Word), then I am nothing!”

Hence, we need to come to Christ’s crib at Christmas with the “Key of Charity”―but to unlock the doors that lead to that “Key of Charity”, we need the “Keys of Faith and Hope.” Having said that (and slept through the above), let us now turn our attention to the first of those “Three Keys”―the “Key of Faith”, or Theological Virtue of Faith, which is NOT AN END IN ITSELF, but a seed that needs to sprout and grow into HOPE and CHARITY (the subject of the next two articles before Christmas).

The Key of Faith―Faith is Key!

What then is this supernatural virtue of Faith which is the first and primary benefit we receive from the Holy Spirit? Without Faith everything else in Christianity is absolutely meaningless. Call it divine Faith. Divine Faith is the virtue or power which enables us to assent with our intellects to the truths revealed by God, not because we fully understand them all, but only on the authority of God―Who can neither deceive nor be deceived. We assent with our minds. We consent with our wills. We assent with our minds to believe everything which God has revealed. We consent with our wills to practice all that we must practice. St. Thomas Aquinas says: “To one who has Faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without Faith, no explanation is possible!”

God, through Holy Scripture, could put it any more clearly: “Without Faith, it is impossible to please God” (Hebrews 11:6). What part of that quote is it that we cannot understand? There is no way around that, there is no exception to that. The full quote reads as follows: “Without Faith, it is impossible to please God. For he that cometh to God, must believe that He is, and is a rewarder to them that seek Him” (Hebrews 11:6). Other part of Holy Scripture re-affirm and confirm this truth: “All that is not of Faith is sin!” (Romans 14:23). “The just man liveth by Faith” (Romans 1:17). “By grace, you are saved through Faith” (Ephesians 2:8). “He that believeth in the Son, hath life everlasting. But he that believeth not the Son, shall not see life; but the wrath of God abideth on him” (John 3:36). “For whatsoever is born of God, overcometh the world: and this is the victory which overcometh the world, our Faith” (1 John 5:4). “And Jesus said to them: ‘You are from beneath, I am from above! You are of this world, I am not of this world! Therefore I said to you, that you shall die in your sins. For if you believe not that I am He, you shall die in your sin!’” (John 8:23-24). “Woe to them who believe not God―they shall not be protected by Him!” (Ecclesiasticus 2:15).

Yet Our Lord and God knows that most will not believe Him and that most will not embrace the Faith entirely―picking and choosing only what appeals to them and satisfies them. “The Son of man, when He cometh, shall He find, think you, Faith on Earth?” Luke 18:8). “Not everyone that saith to Me: ‘Lord! Lord!’ shall enter into the Kingdom of Heaven: but he that doth the will of My Father Who is in Heaven, he shall enter into the Kingdom of Heaven. Many will say to Me in that day: ‘Lord! Lord! Have not we prophesied in Thy Name, and cast out devils in Thy Name, and done many miracles in Thy Name?’ And then will I profess unto them: ‘I never knew you! Depart from Me!’” (Matthew 7:21-23). “Why call you Me, ‘Lord! Lord!’ and do not the things which I say?” (Luke 6:46).

“And a certain man said to Him: ‘Lord! Are they few that are saved?’ But He said to them: ‘Strive to enter by the narrow gate; for many, I say to you, shall seek to enter, and shall not be able. But when the master of the house shall be gone in, and shall shut the door, you shall begin to stand without, and knock at the door, saying: ‘Lord! Open to us!’ And He, answering, shall say to you: ‘I know you not, whence you are!’ Then you shall begin to say: ‘We have eaten and drunk in Thy presence, and Thou hast taught in our streets!” And He shall say to you: ‘I know you not, whence you are! Depart from Me, all ye workers of iniquity!’ There shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth, when you shall see Abraham and Isaac and Jacob, and all the prophets, in the Kingdom of God, and you yourselves thrust out!’” (Luke 13:23-28).

Ignorance of the Faith

Faith is all about knowing the Word of God―what God has revealed, what God has taught and what God wants us to do. Our Lord Himself reinforced that fact at the Last Supper, when He said: “If you love Me, keep My commandments … He that hath My commandments, and keepeth them; he it is that loveth Me … If any one love Me, he will keep My word … He that loveth Me not, keepeth not My words … If you keep My commandments, you shall abide in My love” (John 14:15, 14:21-24; 15:10). It takes a brave man or a fool to say: “I’m not interested in learning about Your words! I’m not interested in knowing what Your commandments are! I’m not interested in keeping Your commandments or following Your word!” Hell is full of such brave men and fools!

Pope St. Pius X also speaks of this damnation through neglect or lack of knowledge through ignorance: “We are forced to agree with those who hold that the chief cause of the present indifference and the serious evils that result from it, is to be found above all in ignorance of things divine … It is a common complaint, unfortunately too well founded, that there are large numbers of Christians, in our own time, who are entirely ignorant of those truths necessary for salvation. We refer not only to the masses or to those in the lower walks of life — but We refer to those especially who do not lack culture or talents and, indeed, are possessed of abundant knowledge regarding things of the world but live rashly and imprudently with regard to religion. It is hard to find words to describe how profound is the darkness in which they are engulfed, and, what is most deplorable of all, how tranquilly they repose there. They rarely give thought to God! … They have no conception of the malice and baseness of sin; hence they show no anxiety to avoid sin or to renounce it. And so they arrive at life's end in such a condition … and then calmly face the fearful passage to eternity without making their peace with God. And so Our Predecessor, Pope Benedict XIV, had just cause to write: ‘We declare that a great number of those who are condemned to eternal punishment, suffer that everlasting calamity because of ignorance of those mysteries of Faith which must be known and believed in order to be numbered among the elect.’ … How many and how grave are the consequences of ignorance in matters of religion! It is indeed vain to expect a fulfillment of the duties of a Christian by one who does not even know them.” (Pope St. Pius X, encyclical Acerbo Nimis, 1905).

Are You Losing It? Our Lady warns of dangers to the Faith

Faith is absolutely necessary for salvation. This means in the simplest terms that it is simply impossible for us to get to Heaven unless, during life, we have believed in God. It is impossible to please God without Faith. “For if you believe not that I am He, you shall die in your sin” (John 8:24).

That Faith is meant, not just for a few, but for the whole world, as shown by the following words of Our Lord: “Going therefore, teach ye all nations; baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you” (Matthew 28:19-20). “He that heareth you, heareth Me; and he that despiseth you, despiseth Me; and he that despiseth Me, despiseth Him that sent Me” (Luke 10:16). “He that believeth and is baptized, shall be saved: but he that believeth not shall be condemned” (Mark 16:16).

We have to believe ALL things, that is to say all the dogmas, that the Church teaches us, and not just some of them.

Yet, Our Lady, over the last few hundred years, has given us ample warning about a time when the Faith will be lost—lost by most people, lost by priests and religious orders, lost by bishops, and lost even by Rome itself.

Warning About the Faith at La Salette

Our Lady had the following tragic things to say at La Salette: “Woe to the priests and to those dedicated to God who, by their unfaithfulness and their wicked lives, are crucifying my Son again! … The chiefs, the leaders of the people of God, have neglected prayer and penance, and the devil has bedimmed their intelligence … The devil will resort to all his evil tricks to introduce sinners into religious orders, for disorder and the love of carnal pleasures will be spread all over the Earth … Lucifer, together with a large number of demons, will be unloosed from Hell; they will put an end to Faith little by little, even in those dedicated to God.”

“Several will abandon the Faith, and a great number of priests and members of religious orders will break away from the true religion; among these people there will even be bishops … Rome will lose Faith and become the seat of the Antichrist.”

Our Lady warns of those who “will preach another Gospel contrary to that of the true Christ Jesus, denying the existence of Heaven.”

“Evil books will be abundant on Earth and the spirits of darkness will spread everywhere a universal slackening of all that concerns the service of God … All the civil governments will have one and the same plan, which will be to abolish and do away with every religious principal, to make way for materialism, atheism, spiritualism and vice of all kinds … There will be a kind of false peace in the world. People will think of nothing but amusement. The wicked will give themselves over to all kinds of sin.”

“But the children of the holy Church, the children of My Faith, my true followers, they will grow in their love for God and in all the virtues most precious to me. Blessed are the souls humbly guided by the Holy Ghost! I shall fight at their side, until they reach a fullness of years.”

“I call on the Apostles of the Last Days, the faithful disciples of Jesus Christ, who have lived in scorn for the world and for themselves, in poverty and in humility, in scorn and in silence, in prayer and in mortification, in chastity and in union with God, in suffering and unknown to the world. It is time they came out and filled the world with light. Go and reveal yourselves to be my cherished children. I am at your side and within you, provided that your Faith is the light which shines upon you in these unhappy days. May your zeal make you famished for the glory and the honor of Jesus Christ. Fight, children of light, you, the few who can see. For now is the time of all times, the end of all ends.”

“God will take care of His faithful servants and men of good will.”

As to the Pope, Our Lady speaks of Faith being one of the weapons he must use:”may he, however, be steadfast and noble, may he fight with the weapons of Faith and love.”

The Church Speaks After La Salette

“The apostasy of the city of Rome from the vicar of Christ and its destruction by Antichrist may be thoughts very new to many Catholics, that I think it well to recite the text of theologians of greatest repute. First Malvenda, who writes expressly on the subject, states as the opinion of Ribera, Gaspar Melus, Biegas, Suarrez, Bellarmine and Bosius that Rome shall apostatize from the Faith, drive away the Vicar of Christ and return to its ancient paganism. ...Then the Church shall be scattered, driven into the wilderness, and shall be for a time, as it was in the beginning, invisible; hidden in catacombs, in dens, in mountains, in lurking places; for a time it shall be swept, as it were from the face of the Earth. Such is the universal testimony of the Fathers of the early Church.” (Cardinal Henry Edward Manning, The Present Crisis of the Holy See, 1861, London: Burns and Lambert, pp. 88-90)

Warning About the Faith at Fatima

Our Lady also warned about a future loss of the Faith, nay, more than that—a future mass apostasy throughout the world, when she revealed the so-called Third Secret of Fatima as a warning for our day.

In her fourth memoir, which was written from October-December 1941, Sister Lucy copied the first two parts of the Secret from the text of her third memoir, but added a sentence that is not found there. Sister Lucy gave us the first sentence of the Third Secret when she inserted into her fourth memoir the phrase “In Portugal, the dogma of the Faith will always be preserved etc.” This sentence had not appeared in her previous memoir. Sister Lucy purposely inserted it into her fourth memoir to indicate to us what the final part of the Secret is about.

In 1943, after having been asked by Bishop da Silva to write down the text of the Third Secret, Sister Lucy was finding the task difficult. She declared to the bishop that it was not absolutely necessary to write out the text, “since in a certain manner she had said it.” Sister Lucy was very likely referring to the additional phrase she had inserted into her fourth memoir, “In Portugal, the dogma of the Faith will always be preserved etc.”

The phrase, “In Portugal, the dogma of the Faith will always be preserved etc.” is a promise that the true Faith will be preserved in that country, although in its vagueness it does not state by whom. Yet, if in Portugal the true Faith will be preserved, what does that imply about the rest of the world? The Portuguese Father Messias de Coelho concluded that, “this allusion, so positive about what will happen among us, suggests to us that it will be different around us.”

Father Alonso, the official Fatima archivist had this to say on the Third Secret: “‘In Portugal, the dogma of the Faith will always be preserved’: The phrase most clearly implies a critical state of Faith, which other nations will suffer, that is to say, a crisis of Faith; whereas Portugal will preserve its Faith.”

In the period preceding the great triumph of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, terrible things are to happen. These form the content of the third part of the Secret. What are they? If “in Portugal the dogma of the Faith will always be preserved,” ... it can be clearly deduced from this that in other parts of the Church these dogmas are going to become obscure or even lost altogether.

► Cardinal Pacelli, the future Pope Pius XII, said while still a cardinal:

“I am worried by the Blessed Virgin’s messages to Lucy of Fatima. This persistence of Mary about the dangers which menace the Church is a divine warning against the suicide of altering the Faith, in Her liturgy, Her theology and Her soul…. I hear all around me innovators who wish to dismantle the Sacred Chapel, destroy the universal flame of the Church, reject her ornaments and make her feel remorse for her historical past.

“A day will come when the civilized world will deny its God, when the Church will doubt as Peter doubted. She will be tempted to believe that man has become God. In our churches, Christians will search in vain for the red lamp where God awaits them. Like Mary Magdalene, weeping before the empty tomb, they will ask, “Where have they taken Him?” Cardinal Pacelli said this in 1931. He became Pope Pius XII in 1939.