| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

WELCOME TO THE BIBLE STUDY & BIBLE HISTORY PAGES

A Weekly Bible Study Lesson will be posted each week

A Weekly Bible Study Lesson will be posted each week

The best way to participate in the Bible Study Lesson, is to read a little each day (or a few times a week). It is the same with food, we could not possibly eat, in one single meal, the amount of food we would eat over the course of one week. Review is also important. Too often we only read superficially and within a few days we have forgotten half of what we read. The Bible is the word of God, and, as Holy Scripture says: “Not in bread alone doth man live, but in every word that proceedeth from the mouth of God” (Deuteronomy 8:3; Matthew 4:4) … “And Jesus answered the devil: ‘It is written, that Man liveth not by bread alone, but by every word of God!’” (Luke 4:4). Let us therefore nourish ourselves upon the Word of God, a little at a time.

LESSON 2 : THE ORIGINAL LANGUAGES OF THE BIBLE

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

This article is currently being written. Sections will be posted as they are completed. Please check back later.

|

Can You Speak the Lingo? Or Is It All Greek To You?

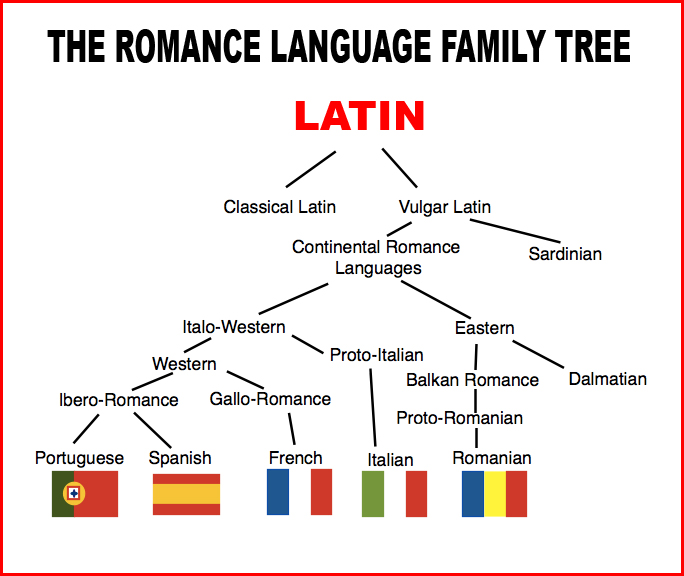

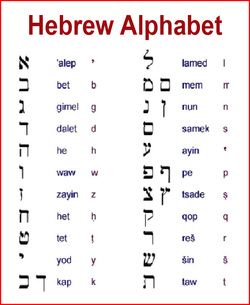

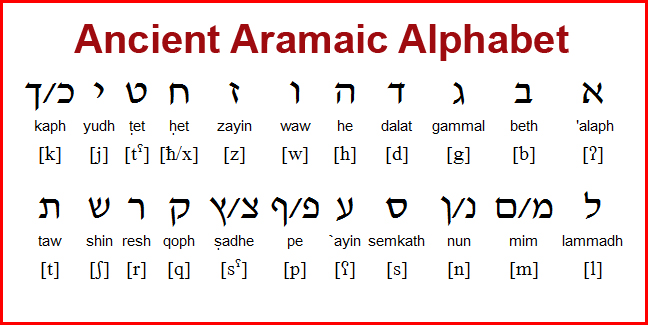

The first human author to write down the biblical record was Moses. He was commanded by God to take on this task, for Exodus 34:27 records God's words to Moses, “Write down these words, for in accordance with these words I have made a covenant with you and with Israel.” And what language did he use? He wrote in his native language, called Hebrew. In What Language was the Bible Originally Written? Priests and seminarians can probably answer that easily enough, but most other people might have only a vague idea that the Bible was written in one of those “dead” languages. Ancient Greek? Latin, perhaps? The Bible was actually written in three different ancient languages: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. While (a modern version of) each of these languages is spoken today, most modern readers of those languages would have some difficulty with the ancient versions used in the Biblical texts. It’s strange to think that we might hardly recognize the most influential book in the world in its original form! Hebrew—the Language of (Most of) the Old Testament Ancient Hebrew was the tongue of the ancient Israelites and the language in which most of the Old Testament was penned. Isaiah 19:18 calls it “the language of Canaan,” while other verses label it “Judean” and “language of the Jews” (4 Kings 18:26; Isaias 36:11, 13; 2 Paralipomenon 32:18; Nehemias 13:24). Ancient Hebrew is a Semitic language that dates back past 1500 BC. Its alphabet consists of 22 characters, all consonants (don’t worry; vowels were eventually added), and is written from right to left. After the Babylonian captivity, Aramaic replaced Biblical Hebrew as the everyday language in Palestine. The two languages were as similar as two Romance languages (e.g. French, Spanish, Portuguese or Italian) or two Germanic languages today. While Hebrew remained the sacred tongue of the Jews, its use as a common spoken language declined after the Jews’ return from exile (538 B.C.). Thus Biblical Hebrew, which was still used for religious purposes, was not totally unfamiliar, but still a somewhat strange norm that demanded a certain degree of training to be understood properly. Despite a revival of the language during the Maccabean era, it was eventually all but replaced in everyday usage by Aramaic. Modern Hebrew can trace its ancestry to Biblical Hebrew, but has incorporated many other influences as well. Hebrew is one of a group of several languages known as the Semitic languages which were spoken throughout that part of the world, then called Mesopotamia, located today mainly in Iraq. Their alphabet consisted of 22 letters, all consonants. (Imagine having an alphabet with no vowels! Much later they did add vowels.) During the thousand years of its composition, almost the entire Old Testament was written in Hebrew. But a few chapters in the prophecies of Ezra and Daniel and one verse in Jeremias were written in a language called Aramaic. This language became very popular in the ancient world and actually displaced many other languages. Aramaic even became the common language spoken in Israel in Jesus’ time, and it was likely the language He spoke day by day. Some Aramaic words were even used by the Gospel writers in the New Testament. What’s Aramaic?

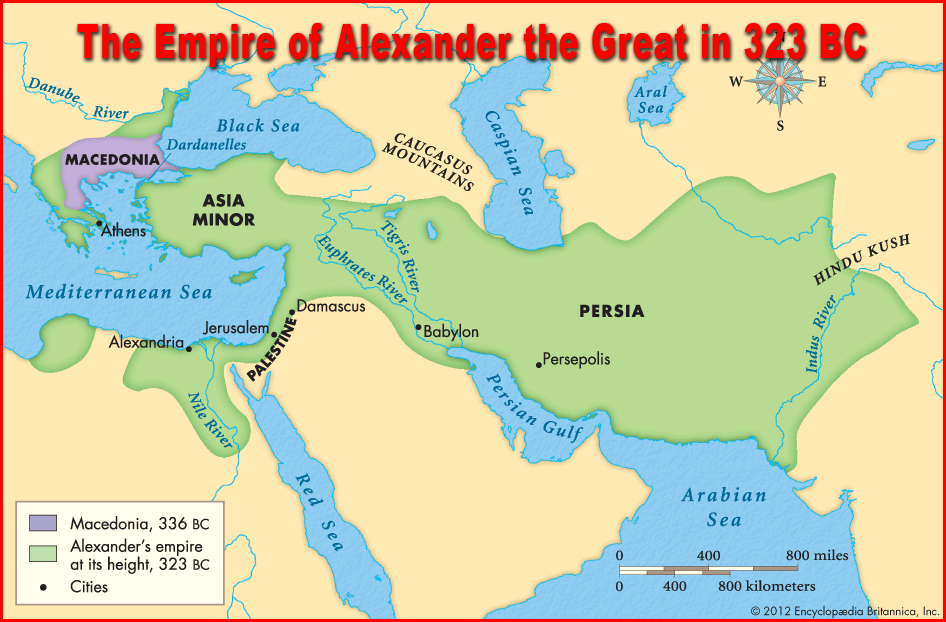

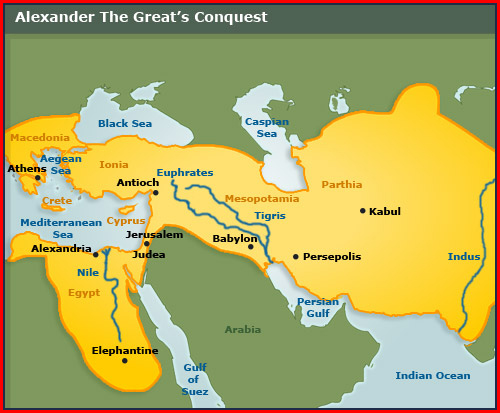

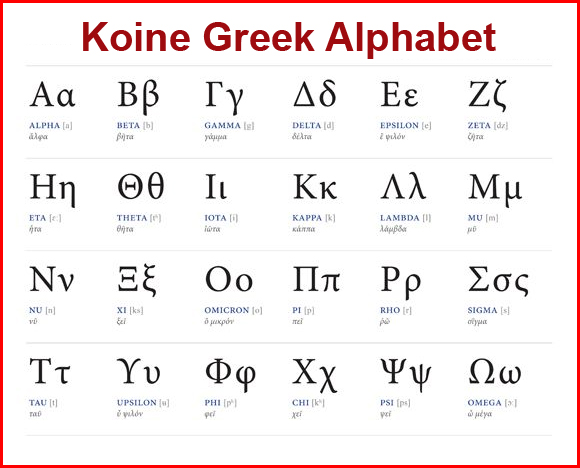

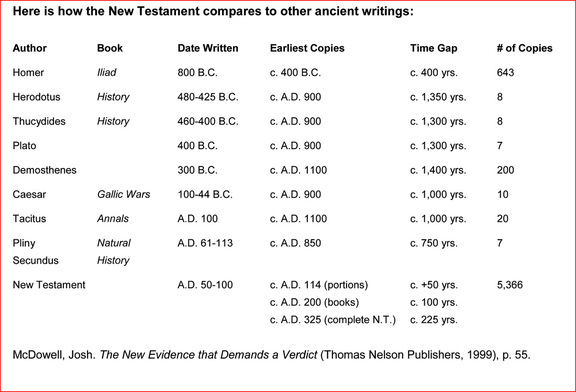

Ancient Aram, bordering northern Israel and now called Syria, is considered the linguistic epicenter of Aramaic, the language of the Arameans who settled the area during the Bronze Age circa 3500 BC. Ancient Aramaic originated among the Arameans in northern Syria (see map at top of the left column) and became widely used under the Assyrians. A few passages in the Old Testament were written in Aramaic (Genesis 31:47; Esdras 4:8-6:18, 7:12-26; Jeremias 10:11). Some have compared the relationship between Hebrew and Aramaic to that between modern Spanish and Portuguese: they’re distinct languages, but sufficiently closely related that a reader of one can understand much of the other. Aramaic was very popular in the ancient world and was commonly spoken in Jesus’ time. During its approximately 3,000 years of written history, Aramaic has served variously as a language of administration of empires and as a language of divine worship. It became the lingua franca (bridge language, common language, trade language) of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BC), the Achaemenid Empire (539–323 BC), the Parthian Empire (247 BC–224 AD), and the Sasanian Empire (224–651 AD), and the day-to-day language of Roman Judaea (539 BC–70 AD). It was the language of Jesus, Who spoke a Western Aramaic language during his public ministry. Aramaic's long history and diverse and widespread use has led to the development of many divergent varieties, which are sometimes considered dialects, though they are distinct enough that they are sometimes considered languages. Therefore, there is not one singular, static Aramaic language; each time and place rather has had its own variation. Aramaic is retained as a liturgical language by certain Eastern Christian churches, in the form of Syriac. Aramaic is often spoken of as a single language. However, it is in reality a group of related languages, rather than a single monolithic language—something which it has never been. Some Aramaic languages differ more from each other than the Romance languages do among themselves. Its long history, extensive literature, and use by different religious communities are all factors in the diversification of the language. Some Aramaic dialects are mutually intelligible, whereas others are not mutually intelligible. The major Aramaic dialect Syriac is the liturgical language of Syriac Christianity, in particular the Assyrian Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Saint Thomas Christian Churches in India, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church, Ancient Church of the East, Syriac Catholic Church and the Maronite Church. The New Testament Was All Greek To Most People The New Testament, however, was written in Greek. This seems strange, since you might think it would be either Hebrew or Aramaic. However, Greek was the language of scholarship during the years of the composition of the New Testament from 50 to 100 AD. Whereas the Classical Greek city states used different dialects of Greek, a common standard, called Koine (meaning “common”), developed gradually in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, as a consequence of the formation of larger political structures (like the Greek colonies, Athenian Empire, and the Macedonian Empire) and a more intense cultural exchange in the Aegean area, or in other words the Hellenization of the empire of Alexander the Great. What’s interesting about Biblical Greek is that it didn’t use a high-class or complicated style; it was written in Koine (common Greek), a language that could be understood by almost anyone, educated or not. The fact is that many Jews could not even read Hebrew anymore, and this disturbed the Jewish leaders a lot! Ever since the conquests of Alexander the Great, the Jews had been “Hellenized” (“Greek-ified”, so to speak). After Alexander, Palestine was ruled by the Ptolemies and the Seleucids for almost two hundred years. Jewish culture was heavily influenced by Hellenistic (Greek) culture, and Koine Greek was used not only for international communication, but also as the first language of many Jews. This development was furthered by the fact that the largest Jewish community of the world lived in Ptolemaic Alexandria (Egypt), also called the Diaspora. Many of these diaspora Jews would have Greek as their first language. The New Testament Gospels and Epistles were only part of a Hellenistic Jewish culture in the Roman Empire, where Alexandria had a larger Jewish population than Jerusalem, and Greek was spoken by more Jews than Hebrew. You could, in a broad sense, compare the heavy influence of the Greek language to the English language that predominates in the United States of America. Even though children are born to ethnic parents in the USA, for the most part, they no longer speak the native language of their parents, but only English. So, around 300 BC, a translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew into Greek was undertaken, and it was completed around 200 BC. Gradually this Greek translation of the Old Testament, called the Septuagint, was widely accepted and was even used in many synagogues. It also became a wonderful missionary tool for the early Christians, for now the Greeks and Gentiles could read God’s Word in their own tongue or in the prevailing language of the time. Lost in Translation? Some people have the idea that the Bible has been translated so many times, that it has become corrupted through stages of translating. If the translations were being made from other translations, they would have a case. But translations are actually made directly from original Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic source texts based on thousands of ancient manuscripts. The Old Testament's accuracy was confirmed by an archaeological discovery in 1947, along today's West Bank in Israel. The Dead Sea Scrolls contained Old Testament Scripture dating 1,000 years older than any manuscripts we had. When comparing the manuscripts at hand with these, from 1,000 years earlier, we find agreement 99.5% of the time. And the 0.5% differences are minor spelling variances and sentence structure, that doesn't change the meaning of the sentence. Regarding the New Testament, it is humanity's most reliable ancient document. We have thousands of copies of the New Testament, all dated closely to the original writing. In fact, we are more sure the New Testament remains as it was originally written by its writers, than we are sure of writings we attribute to Plato, or Aristotle, or Homer's Iliad. The Alexandrian Miracle?In third-century BC, in Alexandria, Egypt, one of the last of the pharaonic rulers—Ptolemy Philadelphus II—wanted his Jewish subjects to have access to their own holy books. Because of the far-reaching conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek had become the language of the eastern Mediterranean, and Egypt was no exception. Those who identified themselves as Jewish could no longer read their own Scriptures, and Philadelphus was keen to help. More importantly, he wished to collect a compilation of these writings, in Greek, for Alexandria’s famous library, which boasted a copy of every book in the known world. Calling together seventy of his best scholars, he charged them with a massive undertaking: each one was to work independently, carefully translating Hebrew texts to Greek.

And then, according to legend, an extraordinary thing happened. When Ptolemy compared the seventy different translations, he found that each copy was precisely like the next. There could be no explanation other than that God himself directed the translators in their work. This new Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, known as the Septuagint (from the Greek for seventy), was perfect, authoritative, useful, and—above all—divinely inspired. Is this legend true? Some maintain that it is. Many scholars, however, prefer to consider this story not for its factual merit but for what it tells us about the historical moment. For one thing, it reveals anxieties over the issue of words and texts and their relationship to ideas of holiness. Does the Bible “mean” something different in its original language than it does in translation? This story about Ptolemy Philadelphus II suggests the opposite: in whatever language, the Bible is still a holy book because God directs the work of the translators. |

Web Hosting by Just Host