| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT

THE CENACLE OR THE UPPER ROOM?

THE CENACLE OR THE UPPER ROOM?

With the Last Supper not too far behind us, and the feast of Pentecost upon us,

let us refresh our memories on this most important of places.

let us refresh our memories on this most important of places.

|

|

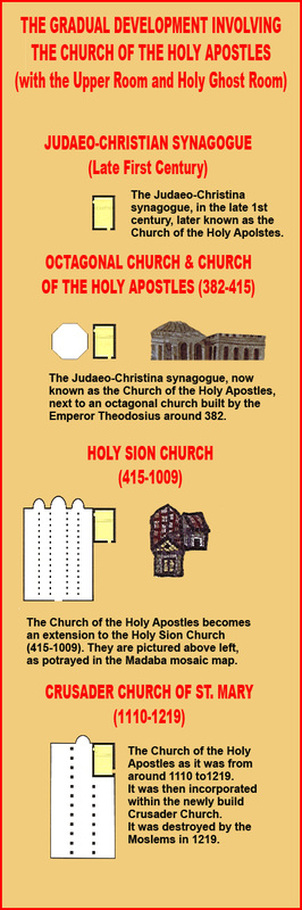

THE CENACLE OR "UPPER ROOM" (Part 1) The Home of St. Mark

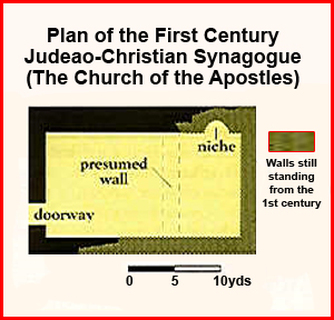

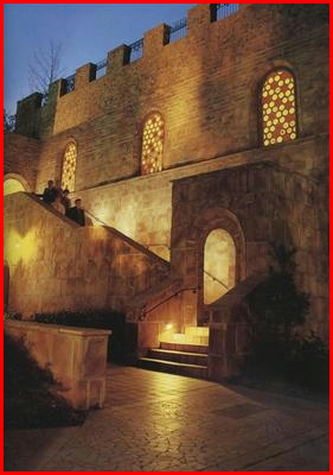

According to early Christian tradition, the “Upper Room” was in the home of Mary the mother of John Mark. He was the author of the Gospel of Mark (and presumably also the young man who fled naked, leaving behind his linen garment, to escape the authorities when Jesus was arrested in the garden at Gethsemane, an event he recorded in Mark 14:51). Some say it was Nicodemus, or Joseph of Arimathea, who owned the building. The original building was a synagogue (a house of prayer) and later was probably used by the early Jewish Christians. The owner of the house, in which was found the Upper Room of the Last Supper, is not mentioned in Scripture; but he must have been one of the disciples of Our Lord, since Christ bids Peter and John say, “The Master says”. Disciples Meeting Place This house was a meeting place for the followers of Jesus inside the city walls of Jerusalem. In this building Christ showed Himself after His Resurrection; here took place the election of Matthias to the Apostolate and the sending of the Holy Ghost on the first Pentecost Sunday; here the first Christians assembled for the “breaking of bread” or the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in its early format; here Peter and John came when they had given testimony after the cure of the man born lame, and Peter after his liberation from prison came here for refuge after an angel of the Lord released him from prison. Acts 12:12-16 says a maid named Rhoda was so overjoyed at recognizing his voice that she left him knocking at the outer gate while she went to tell the gathered disciples. Council of Jerusalem Here, perhaps, was the council of the Apostles held (the Council of Jerusalem). It was for a while the only church in Jerusalem, the mother of all churches, known as the Church of the Apostles or of Sion. The hall was large and furnished as a dining-room. While the term “Cenacle” means "dining room" it refers only to the “Upper Room,” the building contains another site of interest. A niche located on the lower level of the same building is associated by tradition with the burial site of King David, marked by a large monument set up by 12th century Crusaders. The Cenacle is also connected to the house where Virgin Mary lived among the Apostles until her death or dormition, an event celebrated in the nearby Church of the Dormition. Destruction of Jerusalem In 70 A.D. the Roman general Titus suppressed the First Jewish Revolt (66-70 A.D.) by utterly destroying Jerusalem and burning the Temple. The first-century historian Josephus tells us that the destruction reached the farthest corners of the city and was so complete that someone passing by would not know a city ever stood there. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the building was spared during the destruction of Jerusalem, though the Catholic archeologist, who spent several decades (1969-2002) in a monastery in Jerusalem, Fr. Pixner, OSB (1921-2002), thinks it was probably rebuilt right after the war, and claims three walls of that structure are still existing: the North, East and South walls of the present King David’s Tomb. It may even be that the building was partially destroyed and required extensive work to restore it—which would be tantamount to rebuilding. Post-Destruction Era In any case, Fr. Brixner is of the opinion that after this destruction, returning Judaeo-Christians, in the late first century, rebuilt the Judaeo-Christian synagogue on the site they identified with the Cenacle (the Upper Room, where the Last Supper was held), and which was the center of the primitive community that formed around St. James, "the brother of the Lord" (Galatians 1:19) and the first bishop of Jersuslaem. It must be remembered that in those days, Christian meant Catholic (the word Catholic had not yet come into use) and during the first three centuries, due to the intermittent Roman persecution of Christians, it was forbidden to build any Christian churches as places of worship. The most probable period in which it was built was between 70 and 132. According to the respected Church historian Eusebius, during those years there was a flourishing Judaeo-Christian community in Jerusalem presided over by a series of 13 Judaeo-Christian bishops (Catholic bishops of Jewish descent). Early Church writers identified this Judaeo-Christian synagogue as the Church of the Apostles. At the time of the destruction of Jerusalem (70 AD) there were anywhere from 390 to 480 synagogues in the city of Jerusalem. Synagogue Church? Why was this ancient Judaeo-Christian synagogue, on Mt. Sion, called the Church of the Apostles? Bishop St. Epiphanius (315-403 A.D.), a native of the Holy Land, transmitted to us the following information: When the Roman emperor Hadrian visited Jerusalem in 130/131 A.D., there was standing on Mt. Sion "a small church of God. It marked the site of the Upper Room, to which the disciples returned from the Mount of Olives after the Lord had been taken up [Acts 1:13]. It had been built on that part of Sion." The ancient sanctuary on Mt. Sion known to St. Epiphanius could only have been a Judaeo-Christian synagogue, for the building of Christian "churches" was only made possible after the Roman Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan (313 A.D.). Who built this synagogue-church — already standing on the southwestern hill of Mt. Sion in 130 A.D. — in memory of the place of the Last Supper and the Pentecost event? Some information comes from a tenth-century Patriarch of Alexandria, named Euthychius (896-940 A.D.), who wrote a history of the church based on all the ancient sources that were available to him. According to Euthychius, the Judaeo-Christians who fled to Pella to escape the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. "returned to Jerusalem in the fourth year of the emperor Vespasian, and built there their church" (Migne, ed., Patrologia Latina, Vol. III, p. 985). The fourth year of Vespasian was 73 A.D., the year Masada, the last outpost of the Jewish rebellion, fell to the Romans. The Judaeo-Christians returned to Jerusalem under the leadership of Simon Bar-Kleopha (Simon, son of Cleophas), who was the second bishop of Jerusalem after James, "the brother of the Lord," and, like Jesus, a descendant of the royal Davidic family. The Judaeo-Christians probably built their church, at that time called a synagogue, sometime in the decade after 73 A.D. For its construction, they could have used some of the magnificent stones from Herod's destroyed Temple. If that is so, the event may in fact be referred to in one of the apocryphal Odes of Solomon composed about 100 A.D. by a rival sectarian Judaeo-Christian group. The fourth ode begins: "No man can pervert your holy place, O God, nor can he change it, and put it in another place, because [he has] no power over it. Your sanctuary you designed before you made special places." Church of the Apostles The Roman emperor, Theodosius I, built an octagonal church (the “Theodosian Church” or “Holy Sion Church”) alongside the synagogue that was named “Church of the Apostles”. The Theodosian Church, probably started in AD 382, was consecrated by John II, Bishop of Jerusalem in 394. It was visited in 404 by St. Paula of Rome. Some years later, around 415, Bishop John II enlarged the Holy Sion Church, transforming it into a large rectangular basilica with five naves, always alongside the Church of the Apostles. This building was later destroyed by Persian invaders in 614 AD and shortly after partially rebuilt by patriarch Modestus. Destroyed by Moslems In 1009 the church was razed to the ground by the Moslems and shortly after replaced by the Crusaders with a five-aisled basilica named “Saint Mary”. When the church was again destroyed in 1219, the section containing the former synagogue, including its upper-floor room (the Cenacle) were spared. In the 1330s, it passed into the custody of the Franciscan Order of Friars, who maintained the structure until 1552, when the Moslems of the Ottoman Empire took possession of it. After the Franciscan friars’ eviction in 1591, this room was transformed into a mosque. Christians were not officially allowed to return until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The historical building is currently owned by the State of Israel. The Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, which had previously owned the building and sought its return, will have administrative control over the Cenacle itself after the Vatican-Israeli accord. Today part of the site is taken by the smaller church of the Dormition Abbey (in honor of Our Lady having died there). In this new basilica, it is thought that the Cenacle occupied a portion of two aisles on the right (southern) side of the altar. The Church of the Dormition, the Church of Our Lady, is a new building erected by the Emperor William in commemoration of his visit to Jerusalem in 1898. It was completed in 1910. Its design follows that of the Cathedral of Aix la Chapelle. Since at least the fourth century, the Cenacle, the site of the Last Supper and the descent of the Holy Ghost on Pentecost Sunday, has been a popular Christian pilgrimage site on Mount Sion in Jerusalem. It is well-documented in the narratives of many early pilgrims, such as Egeria, who visited it in 384. The building has experienced numerous cycles of destruction and reconstruction, culminating in the Gothic structure which stands today. ‘Fighting’ over the Building!

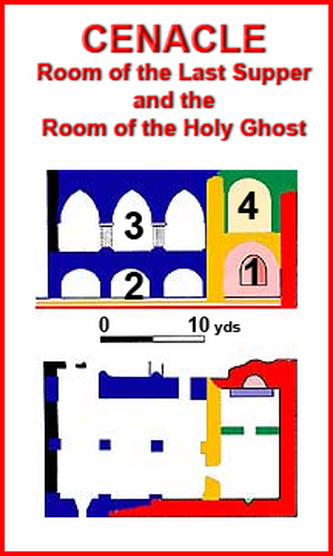

In Jerusalem, just outside the Zion Gate of the old city near the crest of Mount Sion, often called Christian Sion, lie the partial remains of an ancient synagogue consisting of a niche, walls, floors, and foundations, incorporated into a building now venerated by both Jews and Christians. For Jews the site is the traditional location of David's Tomb (the pseudo‐tomb, not the actual tomb) memorialized by a small synagogue on the first floor. Christians commonly regard this site as that of the ancient location of the Upper Room often referred to as the Cenacle or the Coenaculum. A memorial to this heritage, dating to the 14th century, consists of the reconstructed Room of the Last Supper and the adjoining Chapel of the Holy Spirit, both of which are found on the second floor. Though it is a single building that houses the two memorials, each has a separate entrance. The formal name of this ancient, Judeo‐Christian synagogue, during the second and third centuries, is now unknown. In the fourth and fifth centuries, however, Christians referred to the building in a variety of ways. Eusebius called it the “Holy Church of God”. St. Cyril of Jeruslaem said it was the “Upper Church of the Apostles.” Epiphanius said it was a small “Church of God.” Theodosius said it was Holy Sion, which is the “mater omnium ecclesiarum” or the Mother of all Churches. With the later construction of the Basilica of Hagia Sion (Holy Sion) in the early fifth century the synagogue became of less significance. For a brief period it served as the repository of the bones of St. Stephen. Later it functioned simply as a side chapel. Centuries later it became known as the Tomb of David, which remains its name to the present day. For more than a thousand years Mt. Sion was under Christian domination and a place of Christian memorials and churches. During this period, there were times when control of the Holy Places was lost due to Moslem invasions: as was the case with the Persian invasion of 614 and the Islamic occupation of 1009–1099. The pseudo‐Tomb of David, the remnants of this ancient synagogue, remained under Islamic control from 1219, except for the limited Franciscan occupancy of 1335–1551, until taken by the Israelis in 1948. Today it comes under the jurisdiction of the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs. There is no scholarly consensus as to the identity of the original synagogue. Nevertheless, both Christians and Jews relying on the statement by Epiphanius , today claim it as their own. Writing late in the fourth century, Epiphanius claimed, in chapter 14 of his work De Mensuris et Ponderibus, that when the Roman Emperor Hadrian (76‐138) visited Jerusalem (around 131/132), a small “Church of God” and “seven synagogues” existed on Mount Sion. He wrote: Epiphanius wrote: “Hadrian… [135 A.D.] found the city entirely raised to the ground and the Temple of God destroyed and tramped upon, with the exception of some houses and a certain small church of the Christians, which had been constructed in that place, in which the disciples, after the Savior was taken up to heaven from Mount Olivet, betaking themselves, mounted to the Cenacle.” Through Persecutions Christians hold that this site is that of the Upper Room as well the location where the Holy Spirit descended upon Our Lady and the Apostles, and they argue that the present‐day remains are those of this small “Church of God”. The Jews claim it as one of seven synagogues of the Jews observed by Hadrian. The matter remains in scholarly dispute as well and there is no clear consensus of scholarly opinion. Some literary sources and archaeological data support the existence of a Judaeo‐Christian synagogue on Mt. Sion in the second century. On the other hand, the exclusion of Jews from Jerusalem for a time, the Roman persecution of Christians, and the presence of the Roman Tenth Legion on Mt. Sion are arguments against it. However, those who argue against it fail to recognize that the Church managed to exist in hidden pockets throughout the Roman Empire. The fact that the Romans were occupying the Holy Land does not mean that it is no longer the Holy Land, nor does it change the fact that the site of the Last Supper and Pentecost remains the site no matter what happens in the future. A postponement of religious worship does not change the fact that it was a site of religious worship. An early account by a pilgrim from Bordeaux, possibly a Judaeo‐Christian who visited Jerusalem in 333, referred to the tradition of seven synagogues on Mount Sion. This visitor wrote: “Inside Sion, within the wall, you can see where David had his palace. Seven synagogues were there, but only one is left–the rest have been ‘plowed and sown’ as was said by the prophet Isaias” (Pilgrim of Bordeaux, 592). One Room of Two? Room for More? With respect to the Upper Room, the question is—was there but a single upper room put to use by the disciples of Jesus of Nazareth at the time of the Passover? St. Luke, the author of both his Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, employs two different Greek words as a variant for Upper Room (Luke 22:12 & Acts 1:13)—thus leading to conjecture that the rooms of the Last Supper and that of Pentecost, were two different rooms. These two passages mark events in the roughly eight‐week period from the Passover through Pentecost. The Greek word anágaiǒn refers to the venue of the Last Supper and the Greek word hupěrōiǒn refers to the place where the disciples resided at the time of the Ascension and presumably at Pentecost. In his Vulgate translation of the New Testament, Jerome rendered these two Greek words by the single Latin word “coenaculum”, or “cenaculum”, meaning dining room which was customarily located on a second floor in Greco‐Roman multi‐story homes. At times translators render “coenaculum” and “cenaculum” into English as “cenacle”. In early Christian tradition the location of the Upper Room was the home of Mary the mother of John Mark (Acts 12:12). In his Gospel, John Mark, presumably the young man who followed soldiers taking Jesus to the courtyard of the high priest in the Upper City, and escaped naked when in attempting to grab him they got his sleeping garment instead (Mark 14:51), also uses the Greek word anágaiǒn for Upper Room in reference to the venue of the Last Supper (Mark 14:15). Below you see a photo of the room that is held to have been the location for the Descent of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost. It is an adjoining room to that of the Last Supper. It is known as the "The Holy Spirit Room." Architectural evidence suggests that this place is older than the "Last Supper" room. The white cenotaph and the cupola above it are later additions made by the Muslims because of the Tomb of David's present on the first floor (street level). |

Web Hosting by Just Host