| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

The Greatest and Most Important Week in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

THE ORIGINS AND ROLE OF THE SANHEDRIN

Meaning of the Word “Sanhedrin”

The term “Sanhedrin”, also spelled “Sanhedrim”, originates from the Greek word synedrion, which means “sitting together,” hence an “assembly” or “council”― that means “assembly” or “council” and dates from the Hellenistic (Greek) period, but the concept is one that goes back to the Old Testament days.

Scriptural Roots

In the Holy Scripture we read that God commanded Moses to “bring Me seventy of Israel’s elders who are known to you as leaders and officials among the people. Have them come to the Tent of Meeting, that they may stand there with you” (Numbers 11:16). Also, in the sixteenth chapter of Deuteronomy, we read in verse 18, “You shall appoint for yourselves judges and officers in all your towns which the Lord your God is giving you, according to your tribes and they shall judge the people with righteous judgment.”

Two Kinds of Sanhedrin

Although eminent sources—the Hellenistic-Jewish historian Josephus, the New Testament, and the Talmud—have mentioned the Sanhedrin, their accounts are fragmentary, apparently contradictory, and often obscure. Hence, its exact nature, composition, and function remain a subject of scholarly investigation and controversy. In the writings of Josephus and the Gospels, for example, the Sanhedrin is presented as a political and judicial council headed by the high priest (in his role as civil ruler); in the Talmud it is described as primarily a religious legislative body headed by sages, though with certain political and judicial functions. Some scholars have accepted the first view as authentic, others the second, while a third school holds that there were two Sanhedrins, one a purely political council, the other a religious court and legislature. Moreover, some scholars attest that the Sanhedrin was a single body, combining political, religious, and judicial functions in a community where these aspects were inseparable.

Greater Sanhedrin and Lesser Sanhedrin

Whatever opinion may be true, what is known is that once the Israelites entered the Promised Land, the land was divided up among the tribes, and in those areas where tribes had their presence, there were towns and villages, and in every town and every village there was to be a court. Every well-organized community must have had one.

There were two classes of rabbinical courts called Sanhedrin, the Great Sanhedrin and the Lesser Sanhedrin. A Lesser Sanhedrin consisted of 23 judges, and it was appointed to each city― its members were the most prominent Jews of the locality and its president the ruler of the synagogue.

But there was to be only one Great Sanhedrin of 71 judges, which among other roles acted as the “Supreme Court”, taking appeals from cases decided by lesser courts. If there were 120 men as heads of families, they had a local court there called a Lesser Sanhedrin. In smaller towns where there were not 120 men as heads of families, there were either or seven judges or, if the town was very small, three judges, who sat as a court, both judge and jury, in all legal matters.

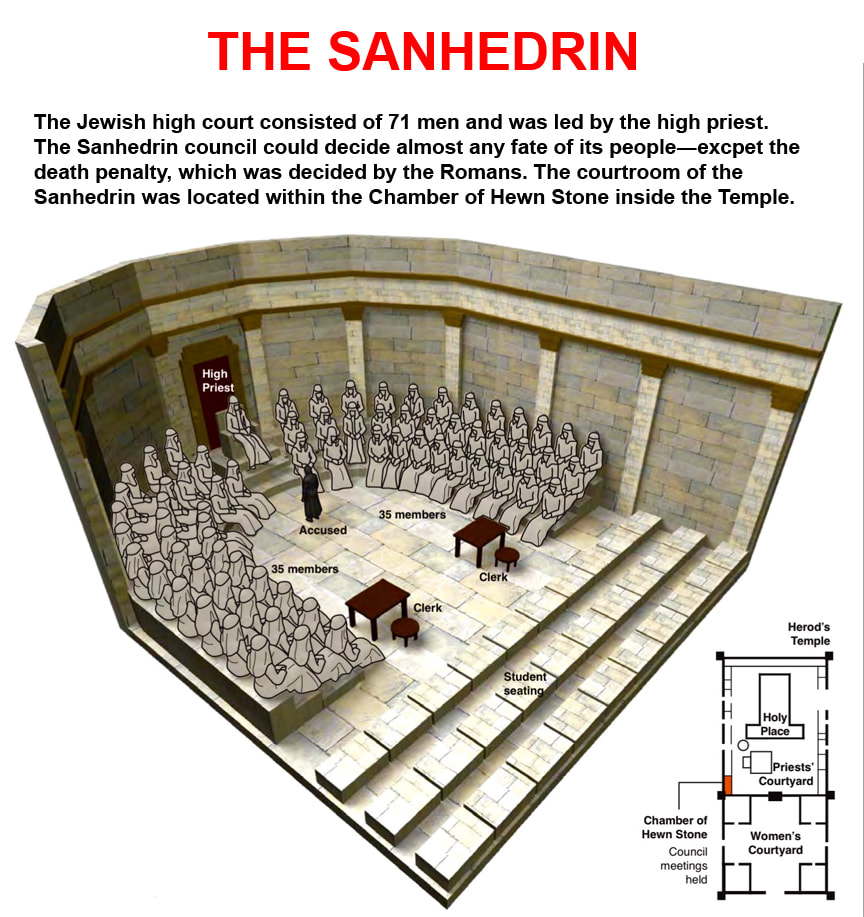

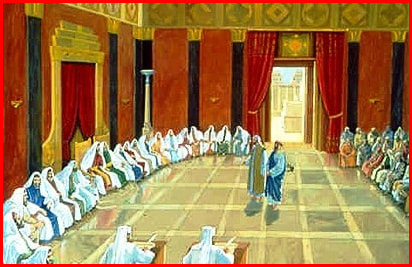

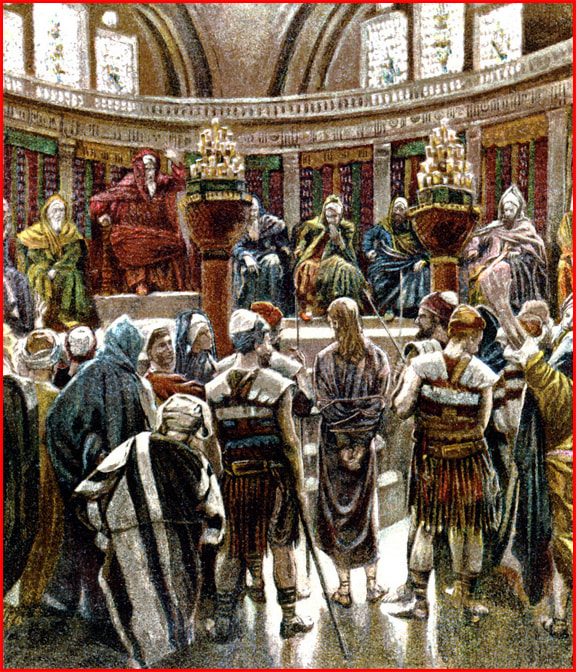

The Great Sanhedrin was the supreme court of ancient Israel, made up of 70 men and the high priest. In the Second Temple period, the Great Sanhedrin met in the Temple in Jerusalem. The court convened every day except festivals and on the Sabbath. The Sanhedrin as a body claimed powers that lesser Jewish courts did not have. Politically, it could appoint the king and the high priest, declare war, and expand the territory of Jerusalem and the Temple. Judicially, it could try a high priest, a false prophet, a rebellious elder, or an errant tribe. Religiously, it supervised certain rituals, including the Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) liturgy. The Great Sanhedrin also supervised the smaller, local Sanhedrins and was the court of last resort, and the Great Sanhedrin was the ultimate judge to whom all questions of law were finally put.

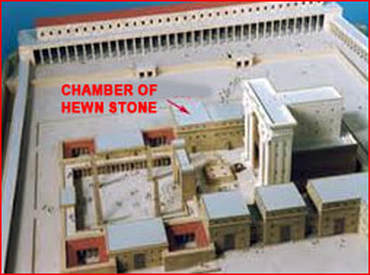

The Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem

In general usage, whenever you hear the term “The Sanhedrin” it normally refers to the Great Sanhedrin, which was composed of the head or president, who had to be a member of the court; the chief of the court, who was second to the president; and sixty-nine general members—thus giving the Great Sanhedrin its total of seventy-one members. The Talmud states that the Great Sanhedrin was to be recruited from the following sources: former High Priests, representatives of the 24 priestly castes, scribes, doctors of the law, and representatives of the most prominent families. In the time of Our Lord, the Second Temple period, the Great Sanhedrin met in the Temple in Jerusalem, in a building called the Hall of Hewn Stones. The Great Sanhedrin convened every day except festivals and the Sabbath day.

The term “Sanhedrin”, also spelled “Sanhedrim”, originates from the Greek word synedrion, which means “sitting together,” hence an “assembly” or “council”― that means “assembly” or “council” and dates from the Hellenistic (Greek) period, but the concept is one that goes back to the Old Testament days.

Scriptural Roots

In the Holy Scripture we read that God commanded Moses to “bring Me seventy of Israel’s elders who are known to you as leaders and officials among the people. Have them come to the Tent of Meeting, that they may stand there with you” (Numbers 11:16). Also, in the sixteenth chapter of Deuteronomy, we read in verse 18, “You shall appoint for yourselves judges and officers in all your towns which the Lord your God is giving you, according to your tribes and they shall judge the people with righteous judgment.”

Two Kinds of Sanhedrin

Although eminent sources—the Hellenistic-Jewish historian Josephus, the New Testament, and the Talmud—have mentioned the Sanhedrin, their accounts are fragmentary, apparently contradictory, and often obscure. Hence, its exact nature, composition, and function remain a subject of scholarly investigation and controversy. In the writings of Josephus and the Gospels, for example, the Sanhedrin is presented as a political and judicial council headed by the high priest (in his role as civil ruler); in the Talmud it is described as primarily a religious legislative body headed by sages, though with certain political and judicial functions. Some scholars have accepted the first view as authentic, others the second, while a third school holds that there were two Sanhedrins, one a purely political council, the other a religious court and legislature. Moreover, some scholars attest that the Sanhedrin was a single body, combining political, religious, and judicial functions in a community where these aspects were inseparable.

Greater Sanhedrin and Lesser Sanhedrin

Whatever opinion may be true, what is known is that once the Israelites entered the Promised Land, the land was divided up among the tribes, and in those areas where tribes had their presence, there were towns and villages, and in every town and every village there was to be a court. Every well-organized community must have had one.

There were two classes of rabbinical courts called Sanhedrin, the Great Sanhedrin and the Lesser Sanhedrin. A Lesser Sanhedrin consisted of 23 judges, and it was appointed to each city― its members were the most prominent Jews of the locality and its president the ruler of the synagogue.

But there was to be only one Great Sanhedrin of 71 judges, which among other roles acted as the “Supreme Court”, taking appeals from cases decided by lesser courts. If there were 120 men as heads of families, they had a local court there called a Lesser Sanhedrin. In smaller towns where there were not 120 men as heads of families, there were either or seven judges or, if the town was very small, three judges, who sat as a court, both judge and jury, in all legal matters.

The Great Sanhedrin was the supreme court of ancient Israel, made up of 70 men and the high priest. In the Second Temple period, the Great Sanhedrin met in the Temple in Jerusalem. The court convened every day except festivals and on the Sabbath. The Sanhedrin as a body claimed powers that lesser Jewish courts did not have. Politically, it could appoint the king and the high priest, declare war, and expand the territory of Jerusalem and the Temple. Judicially, it could try a high priest, a false prophet, a rebellious elder, or an errant tribe. Religiously, it supervised certain rituals, including the Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) liturgy. The Great Sanhedrin also supervised the smaller, local Sanhedrins and was the court of last resort, and the Great Sanhedrin was the ultimate judge to whom all questions of law were finally put.

The Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem

In general usage, whenever you hear the term “The Sanhedrin” it normally refers to the Great Sanhedrin, which was composed of the head or president, who had to be a member of the court; the chief of the court, who was second to the president; and sixty-nine general members—thus giving the Great Sanhedrin its total of seventy-one members. The Talmud states that the Great Sanhedrin was to be recruited from the following sources: former High Priests, representatives of the 24 priestly castes, scribes, doctors of the law, and representatives of the most prominent families. In the time of Our Lord, the Second Temple period, the Great Sanhedrin met in the Temple in Jerusalem, in a building called the Hall of Hewn Stones. The Great Sanhedrin convened every day except festivals and the Sabbath day.

|

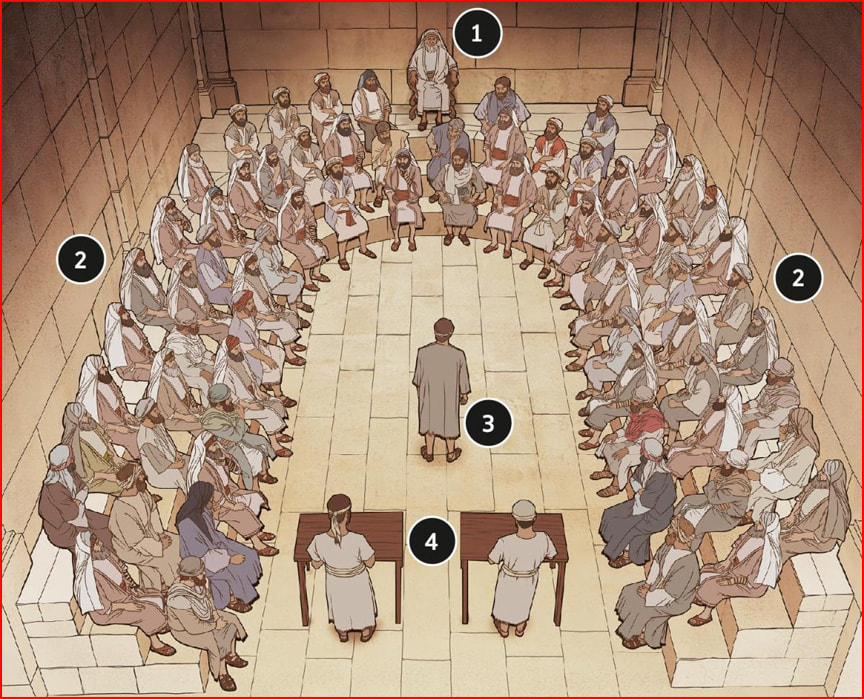

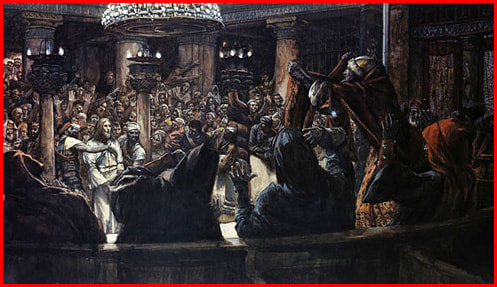

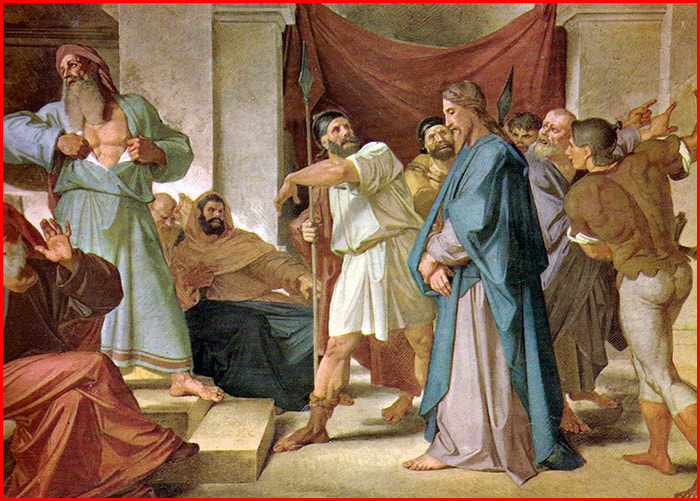

(1) The president of the Sanhedrin

(2) The 70 members of the Sanhedrin (3) The accused person (4) The two clerks of the court of the Sanhedrin |

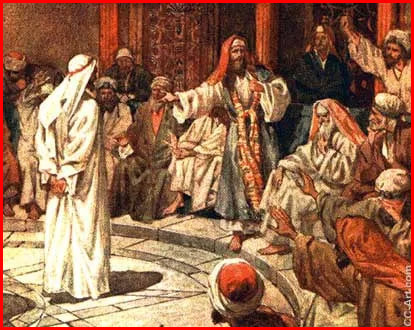

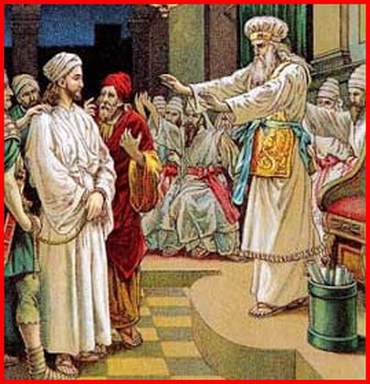

Three Kinds of Members

The composition of the Great Sanhedrin is also in much dispute, the controversy involving the participation of the two major parties of the day, the Sadducees and the Pharisees. Some say the Sanhedrin was made up of Sadducees; some, of Pharisees; others, of an alternation or mixture of the two groups. In the trials of Jesus, the Gospels of Mark and Luke speak of the assembly of the chief priests, elders, and scribes under the high priest, referring to “the whole council [synedrion]” or “their council,” and the Gospel, according to John, speaks of the chief priests and Pharisees convening the council. The general opinion of the composition of the Great Sanhedrin holds that it consisted of seventy-one members, including Its president, the high priest. The members were divided into three groups. The first was that of the “chief priests” and it comprised both those who had already held that office and the most important members of the families from which the high priests were chosen. It was, therefore, the group of the sacerdotal aristocracy, faithful to Sadduccean tenets, and it was the most influential at the time of Jesus. The second was composed of the Ancients, who represented the lay aristocracy, that is, those citizens who because of their wealth or for some other reason exerted a conspicuous influence on public life and could therefore make an effective contribution to the administration of civil affairs. They also were Sadducees. The third group was that of the Scribes, or doctors of the Law, composed for the most part of laymen and Pharisees, but numbering also some priests and Sadducees among its members. Compared with the other two static and aristocratic groups, it formed par excellence the popular and dynamic section of the Sanhedrin. Consequently in the disaster of A.D. 70, the former were swept away in the popular reaction, and the Sanhedrin, from then on, was composed entirely of Scribes. Sanhedrin’s Powers Limited by Invading Kings and Rulers At the time of Jesus, the greatest institution in Judaism next to the high-priesthood was the Great Sanhedrin, the supreme national-religious body. Though rabbinic tradition attributes its foundation to Moses, it really goes back no further than the second century B.C. when the Seleucid kings, who had invaded, captured and ruled Palestine, decreed for Jerusalem a form of local government already in existence in many Hellenistic cities; that is, they gave the council of the Ancients, which administered the city’s affairs, the right to make civil and religious laws, subject to the supreme authority of the king. Since Jerusalem was the capital of Judaism, the decisions of this council had directive force for other Jewish centers in the Seleucid monarchy as well, although these still retained their own local councils, also called “Sanhedrins” ( cf. Matthew 10:17; Mark 13:9). The Great Sanhedrin, then, came into being as a limited form of autonomous government which was permitted to the Jews by foreign kings; hence it was inevitable that it should suffer a loss of actual authority when they were supplanted by a native monarchy or despotism. And that is exactly what happened, first under the nationalist Machabees and Hasmoneans when the Great Sanhedrin enjoyed real power only in those periods in which the monarchy was weak, and later under the tyrannical Herod, who left it the mere shadow of authority. The Great Sanhedrin acquired a great deal of power under the Roman procurators. The Romans applied in Palestine, too, their constant principle of permitting subjected peoples complete freedom in religious matters and a restricted autonomy in civil affairs, and they found it convenient to entrust the administration of this twofold liberty to the great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem. In addition, this body was composed largely of the aristocracy, which in the provinces was much more acceptable to the Romans than the innovators who represented the common people. Type of Work The Great Sanhedrin met daily during the daytime, and did not meet on the Sabbath, festivals or festival eves. The Sanhedrin was convoked by the high priest and held its meetings in the “chamber of hewn stone” (lishkath haggazith), situated at the southwest corner of the inner court which only Israelites might enter. About 30 AD, it supposedly moved to a place called the “shop” (hanuth), the exact site of which is unknown, and perhaps the information itself is incorrect. In special emergencies the Sanhedrin could be called to meet even in the house of its president, the high priest. It was the final authority on Jewish law and any scholar who went against its decisions, was put to death as a rebellious elder. The Great Sanhedrin was led by a president called the nasi (literally meaning “prince”) and a vice president called the av bet din literally meaning "father of the court”). The other 69 members sat in a semicircle facing the leaders. It is unclear whether the leaders included the high priest. The Sanhedrin judged accused lawbreakers, but could not initiate arrests. It required a minimum of two witnesses to convict a suspect. There were no attorneys. Instead, the accusing witness stated the offense in the presence of the accused and the accused could call witnesses on his own behalf. The court questioned the accused, the accusers and the defense witnesses. The Great Sanhedrin dealt with religious and ritualistic Temple matters, criminal matters appertaining to the secular court, proceedings in connection with the discovery of a corpse, trials of adulterous wives, tithes, preparation of Torah Scrolls for the king and the Temple, drawing up the calendar and the solving of difficulties relating to ritual law. Theoretically its jurisdiction extended over all the Jewish world. Practically, at the time of Jesus, it was for Palestine the regular and effective authority, but in Jewish communities outside of Palestine its jurisdiction was rather the exception, and it was progressively weaker the smaller or the more distant the community concerned. The Jews who lived at any great distance appealed to the supreme national council―the Great Sanhedrin―only in extraordinary cases, usually when they could not obtain justice from their local councils or Lesser Sanhedrins. Any religious or civil case in any way connected with the Jewish Law could be judged by the Great Sanhedrin, but its power suffered limitations in various periods as we have just said. This local or Lesser Sanhedrin administered the affairs of its own community, but it did so in accordance with the general norms established by the Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem. It could also function as a tribunal to judge minor matters within its jurisdiction, and it could impose a fine or corporal punishment, up to thirty-nine stripes (cf. 2 Corinthians 11:24). Whoever refused to accept the decision of the local Sanhedrin was excluded from the community for a period of time varying in length. The sentence of perpetual exclusion from the community, actually pronounced very rarely, was an official curse which set the condemned outside the pale of Judaism. The Sanhedrin and the Death Sentence Under the Roman procurators, the decisions of the Great Sanhedrin carried executive weight and the Jewish or Roman police could be called upon to enforce them. Rome had limited its executive power only in the matter of the death sentence, which the Great Sanhedrin could pronounce, but which could not be executed without the express confirmation of the Roman magistrate. Some modem scholars have maintained that even under the procurators the Great Sanhedrin could carry out its own death sentences, but their arguments have convinced very few. The Talmud contradicts itself on this point: in Sanhedrin, (pal., I, 18 a, and VII, 24 b), it says the Great Sanhedrin did not have this power; elsewhere it seems to state that it did. In about 30 AD, the Great Sanhedrin lost its authority to inflict capital punishment—we see that in words that the leaders of Sanhedrin addressed to Pontius Pilate, concerning Jesus: “Pilate therefore went out to them, and said: ‘What accusation bring you against this Man?’ They answered, and said to him: ‘If He were not a malefactor, we would not have delivered Him up to thee!’ Pilate therefore said to them: ‘Take Him you, and judge him according to your law!’ The Jews therefore said to him: ‘It is not lawful for us to put any man to death!’” (John 18:29-31). In any case, to avoid capital punishment as much as possible was a solemn legal principle, which seems to have been faithfully followed, and evidently the death sentence was extremely rare. The rabbis declared that a Sanhedrin was too hotheaded and severe if it passed the death sentence once in every seven years, while Rabbi Tarphon and Rabbi Akiba asserted: “If we had been members of the Sanhedrin, no one would ever have been put to death” (Makkoth, 1, 10). Extracts From Jewish Records About the Sanhedrin Here is some of the data in the rabbinic writings concerning the procedure at the meetings and the rules governing trials. “The Sanhedrin sat in a semicircle so that [its members] could see one another. The president sat in the center and the Ancients sat [according to seniority] on his right and on his left” (Tosephta, Sanhedrin, VIII, 1). “Two clerks of the judges sat before them, one on the right and the other on the left, and they collected the votes of those who would acquit and of those who would convict. Rabbi Judah said there were three; [besides the two] the third collected the votes, both of those who voted for acquittal, and of those who voted for conviction” (Sarah., IV, 3). “The tribunal of the chamber of hewn stone, although composed of seventy-one members, never had fewer [present] than twenty-three. If a member had to leave he first looked about him; if there were twenty-three he went out; otherwise he did not go out until there were twenty-three present. They sat in meeting from the ‘perpetual holocaust’ of the morning until the ‘perpetual holocaust’ of the evening [offered in the Temple at about nine in the morning and four in the afternoon]” (Tosephta, Sarah., VII, 1). “Civil cases may be opened by the defense or by the prosecution; criminal cases may be opened only by the defense. In civil cases a majority of one in favor of the plaintiff or of the defendant is sufficient. In criminal cases a majority of one is sufficient for an acquittal, but for a conviction a majority of two is necessary. In civil cases the judges may review the sentence whether it is in favor of the plaintiff or defendant; in criminal cases, they may review the sentence to acquit but not to convict. In civil cases the judges may all [unanimously] plead in favor either of the plaintiff or the defendant; in criminal cases they may all plead for an acquittal but not for a conviction. That is, a unanimous conviction was not permissible; at least one judge had to plead in favor of the accused. “In civil cases the judge who pleads against the defendant may also plead against the plaintiff, and vice versa; in criminal cases the judge who has argued for conviction may afterward argue for acquittal, but the judge who has argued for acquittal may not gainsay himself and argue for conviction. Civil cases are to be tried by day and settled at night; criminal cases are tried by day and are settled by day. Civil cases may be closed the same day by acquittal or conviction. Criminal cases may be closed the same day provided the sentence is not one of conviction; if the sentence is a conviction, the case is not closed until the following day. For this reason, criminal cases are not to be tried on the vigil of the Sabbath or of feast days. In civil cases and in questions of ritual purity and impurity, the judges express their opinions beginning with the oldest; in criminal cases, they begin from the side [where the youngest members were seated, so that they would not be influenced by the opinions of the older judges]” (Sanh., IV, 1-2). “Witnesses were examined on seven points: [The action took place] in what sabbatical cycle? In what year? In what month? On what day of the month? On what day of the week? At what hour? In what place? ... [When the witnesses have been questioned, then the judges] listen also to the accused if he declares that he has something to say in his own defense and provided there is some basis for what he says. If the judges find him innocent, they free him; otherwise they postpone their decision until the following day. The judges pair off, eat sparingly and drink no wine the entire day, and they discuss the case the whole night; the next morning they go early to the courtroom. Those voting for acquittal say: ‘I was for acquittal and I remain in the same opinion.’ Those voting for conviction say: ‘I was for a conviction and I remain in the same opinion.’ “The judge, who previously maintained that the accused was guilty, may now maintain his innocence, but not vice versa. If they make a mistake in expressing their opinion [state the opposite of what they have stated before] the two clerks of the court correct them. If they find the accused innocent, they free him; otherwise they decide by a vote. If twelve vote for acquittal and eleven for conviction, the accused is declared innocent. If twelve vote for conviction and eleven for acquittal; or if eleven vote for acquittal, eleven for conviction and one does not vote; or if twenty-two vote whether for acquittal or conviction and one does not vote, then the number of judges must be increased. The reason for this was the fact that twenty-three judges were necessary for a quorum as explained above; in the instances mentioned here, one judge was lacking in effect because he did not vote. To what number? By twos until there are seventy-one in all (the full membership of the Sanhedrin). If thirty-six vote for acquittal and thirty-five for conviction, the accused is declared innocent; if thirty-six vote for conviction and thirty-five for acquittal, they continue to discuss the case until one of those inclined to conviction changes his decision” (Sanhedrin, V, 1-5). These and many other rules held in theory, and in any case they were not put in writing until long after the time of Jesus. In his day we may well believe things were quite different in actual practice during turbulent times, or even in normal times, when the judges were swayed by emotional considerations. For the former case we have the example of the mock trial of Zacharias, son of Basis (Baruch), in 67 AD, before a sham tribunal of seventy members meeting in the Temple; the accused, though declared innocent, was killed in the Temple itself (Wars of the Jews, IV, 335-344). For normal times we have the example of Jesus’ trial. The Great Sanhedrin ceased to exist at Jerusalem after the disastrous rebellion against Rome in AD 66–70. However, a Sanhedrin was assembled at Jabneh, and later in other localities in Palestine, that is considered by some scholars to be the continuation of the Jerusalem council-court. Composed of leading scholars, it functioned as the supreme religious, legislative, and educational body of Palestinian Jews; it also had a political aspect, since its head, the nasi, was recognized by the Romans as the political leader of the Jews (patriarch, or ethnarch). This Sanhedrin ceased with the end of the patriarchate in 425 AD, although there have been abortive or short-lived attempts to reinstitute the Sanhedrin in modern times. |

Web Hosting by Just Host