| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE NAME OF THE SAINT YOU WISH TO VIEW

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

|

People look at St. Augustine with mixed feelings. So high does he tower above those of his generation, perhaps above those of every generation, that they look up to him with a certain awe, almost with fear. The very sight of his writings, more, probably, than those of any other writer of the past, frightens us and puts us off; someone has seriously said that merely to read what Augustine has written would take an ordinary man a life-time. Nevertheless, to one who will have courage and come near, it is strange how human, and even how little in his greatness, Augustine is found to be. “I liked to play” he said of himself in his childhood; and there is something of that same delight to be found in him to the very end of his days. Besides, as he himself admits in his book, Confessions, he was a sinner—and it is that capacity we feel much closer to him than we do in relation to his high sanctity. So let us look at St. Augustine from his (and our) starting point of sinfulness and try to rise with him to the degree of sanctity that God intends for us—for the greatest sinners can become the greatest saints. Or, more precisely, the greatest sinners MUST become the greatest saints—so that their great debt for sin can be paid-off by their great penances and virtues of holiness.

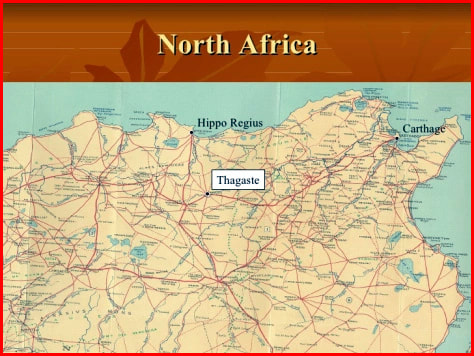

Augustine was born on the 13th of November in the year 354, at Thagaste, a small Roman town in Numidia, North Africa, not far from Hippo, but at some distance from the sea, which the Augustine would never see till he was grown up. Thagaste was a free town, and also a market-town, set at a place where many Roman roads converged; to it the caravans from east and west brought their merchandise, in it, the luxury of Rome was repeated, with the added freedom of Africa. Augustine was the eldest son of Patricius, a well-to-do citizen of the place, a pagan but not a fanatic, whose ideal of life was to get the most out of it he could, without being too particular as to the means. Patricius, at the age of forty, had married Monica, a girl of seventeen, a Christian on both her father’s and her mother’s side. This marriage alone would seem to imply a certain laxity of Faith in the family; the fact that Monica owed most of her religious and moral training to an old nurse confirms it. It cannot be said that the marriage was a happy one. Perhaps it was not intended to be; it was a marriage of convenience and no more. For the pagan Patricius it meant life with a woman who, the older she became, and the more difficult her situation, clung the more to her own religion, and would have nothing to do with his free and easy ways, to call them by no worse name. For Monica it meant a life of constant self-suppression; of abuse even to blows, for Patricius, a choleric, had fits of violent temper; of slander on the part of those who were only too anxious to pander to Patricius, or were jealous of the influence her meek disposition had upon him. Three children were born to them, Augustine the first, but none of them were baptized. In those days a middle course was found. As children were born they were inscribed as catechumens; the baptism might come later, perhaps whenever there was danger of death. Augustine speaks of his brother Navigius, who left a family behind him, and of a sister who died as an abbess of a convent. Augustine grew up among pagan children, apparently in a pagan school, and his morals from the first were no better than theirs. He could steal, he could cheat, he could lie with the best of them; to do these things cleverly and successfully was a mark of talent rather than of vice. He went to school, and he hated it, both its restraint, and the things he had to learn. He was thrashed repeatedly, and when he came home received little commiseration, even from his own mother. His boyhood, from his own description, was an unhappy time; it tended to make him all the more bitter and reckless. But he was a precociously clever child, and in spite of his thrashings, which only made him more obstinate, and his own idleness, he learned more than his companions. He also deplores the sins of theft which he committed by stealing little things out of his parents’ cellar, or from their table, either to gratify his gluttony, or to give to his playfellows. He confesses in particular that one night he and a company of wicked youths stole some pears from a neighbor’s tree near his father’s garden, out of mere wantonness, and a lust of doing what they ought not to do; for the stolen fruit was bad, and they only threw it to the hogs. In this sin he laments the strange seduction of bad company, and of that friendship which is an enemy to the soul. Because some among such companions say: “Let us go, let us do it,” everyone is ashamed not to be shameless. Patricius, who was a worldly man and continued to be an idolater, perceived that his son Augustine had an excellent genius, and a wonderful disposition for learning, and with a view to his future preferment, spared nothing to breed him up a scholar. Here the saint thanks God, that though the persons who pressed him to learn, had no other end in view than to satisfy a desire of penurious riches and ignominious glory; yet divine Providence made a good use of their error, and forced him to learn for his great profit and manifold advantage. Both his father and his mother became ambitious for him; they decided to give him a better education than could be given him in Thagaste. He was sent to Madaura, a prosperous city thirty miles away. But thirty miles, in those days, and for a boy such as Augustine, was a great, separating distance. Here at last he was his own master; the longing he had always had to do just what he liked, without let or hindrance from anyone, was allowed free scope. Augustine humbly acknowledges that he, at that age, fell also into vanity, pleasing himself with the pride of surpassing his companions at play, and loving to have his ears scratched with vain praises, that they might itch the more. A worse curiosity drew him to the dangerous entertainments of those who were older—public shows, plays, and other diversions of the theatre. He declares that God justly turns sin into its own chastisement, its pleasures always leaving a sting, and filling the mind with gall and bitterness. The most fatal rock against which Augustine split, was the execrable vice of impurity, into which he fell in the sixteenth year of his age. He was led into this gulf by reading lascivious plays in Terence, by sloth, by frequenting stage entertainments, and by bad company and example. He studied the pagan classics, for he loved to read and read; he studied not only their literature, but also their ideals and their life. These were exemplified all around him, and he could take part in them as much as he pleased; the pursuit of pleasure at all costs, the wild orgies of the carnivals of Bacchus, the worship of the decadent Roman ideal, smart, sensual, excusing, boldly daring, laughing with approval at every excess of sinful love. Such was the atmosphere the clever, imaginative, craving, reckless Augustine was made to breathe in the city of Apuleius at the age of fifteen; and to face it he had nothing but the flattering encouragement of a pagan father, the timid fear of a Christian mother whose religion he had already learned to despise. He soon became not only a pagan, but an immoral pagan, at the most critical time of his life. The consequences were inevitable. Augustine came home from Madaura addicted to the lowest vices. What was worse, he seemed to have no conscience left; worse still, he had a father who looked upon the same excess as a proof of manhood, the sowing of wild oats now which gave promise of great things later. Only one chain held him, the love he had for his mother. He laughed at her pious ways, he deliberately defied and hurt her; but underneath, though he tried not to admit it to himself, his respect and admiration and affection for her had steadily increased. It was the same on her side, which made the bond all the stronger. Monica’s life with her husband had been unhappy and loveless; and the love she longed to give was poured out on her favorite yet reckless son. The more she loved him, the more she was appalled at the life he was already living, and at the future to which it must inevitably lead. She blamed herself for having been partially the cause of his downfall. She had encouraged the plan of his going to Madaura; she had given him little to protect him while he was there; she would do all she could to win him back, though it was to be the struggle of a life-time. This made her strive all the more for her own perfection; if she was to influence him at all she must herself be true. Since she could say little to him, she would pray for him; she watched him, but it could only be from a distance. And―though he made nothing of it at the time, though he often took delight in hurting her by his boast of wickedness― Augustine knew nevertheless that she prayed, and watched, and loved; and he returned that love, and it grew. The next step in Augustine’s career was to Carthage. It was the center of learning and pleasure in North Africa, and Augustine craved for both. There he lived, from the age of seventeen, learning and loving as he wished, for there was no one to check or guide him. “I went to Carthage,” he wrote later, “where shameful love bubbled round me like boiling oil.” But he was wise enough to know that this was the opportunity of his life; in the midst of his evil living he worked hard. In Carthage, he easily held the foremost place in the school of rhetoric, and applied himself to his studies with so much eagerness and pleasure, that it was with great difficulty he was drawn from them. But his motives were vanity and ambition, and, in his studies, he was pleased and riddled with pride, and puffed up with self-conceit; though he hated open arrogance. Vincent the Rogatist, his enemy, acknowledges that Augustine always loved decency and good manners even in his irregularities; but this was no more than a worldly and exterior decency; for Augustine plunged himself headlong into the filth of impurity. Vice, especially that of impurity, strangely degrades and infatuates the mind, creates an utter distaste and loathing of spiritual things, and renders the soul incapable of raising her thoughts and affections to heavenly objects; this foul vice blinds the understanding, debauches the faculty of reason, and perverts the will and all the other powers of the soul, of which no example can be more amazing than that of King Solomon. At this point his father died, a Christian at the last, being baptized shortly before dying, which cannot but have had an effect on the son; and the pinch of poverty, in consequence of the death, made him work all the harder. He soon became known as the most outgoing and exuberant, the most gifted, and the most sensual scholar in the University of Carthage; a threefold triumph, of each of which he was proud. In the schools of Rhetoric his works were proposed to other students as models; outside the schools he was admired and courted as the reckless addict of love. But the ways of God are strange. One day, in the midst of this thoughtless life, he was studying Cicero. He lighted on the following passage: “If man has a soul, as the greatest philosophers maintain, and if that soul is immortal and divine, then it must necessarily be that the more it has been steeped in reason, and true love, and the pursuit of truth, and the less it has been stained by vice and passion, so much the more surely it will rise above this earth and ascend into the heavens.” This sentence, suddenly come upon, was, he tells us, the beginning of light. It made him restless; his eyes continually went back to it; he began to ask himself whether, after all, he was as happy as he affected. He looked for a solution elsewhere, whether a confirmation of the teaching, or a quieting of his conscience, he did not care. He paid more attention to the other pagan philosophers, but they did not lead him far. He took to the Bible, and for a time it held him; but soon that, too, became insipid, and he put it away. He knew something about the Manichees, with their doctrine that said that there were two eternal spirits―a good and an evil spirit. The Manichees claimed to have a solution for all such problems; above all they pretended to solve them without too much surrender of the ‘good things’ of this world. They said that sin could not be resisted, that passion was a necessity. The doctrine suited Augustine very well as a check to this new thing, conscience, and he accepted it. Augustine became a Manichee. We may now leap over some years. At the age of twenty, to ease his mother of the charge of his education, Augustine left Carthage, and returning to her, Augustine set up a school of grammar and rhetoric at Thagaste. His mother, being a good Catholic, and never ceased to weep and pray for his conversion. She would not sit at the same table, or eat with him, hoping by this severity and abhorrence of his Manichæan heresy, to make him enter into himself. Sometime after, finding her own endeavours to reclaim him unsuccessful, she repaired to a certain bishop, and with tears besought him to discourse with her son upon his errors. The prelate excused himself for the time being, alleging that her son was yet unfit for instruction, being intoxicated with the novelty of his heresy, and bloated with conceit, having often puzzled several Catholics who had entered the lists with him, and were more zealous than learned. “Only pray to our Lord for him,” said he, “your son will at length see his error and impiety.” She still persisted, with many tears, importuning him that he would see her unhappy son; but he dismissed her, saying: “Go your way; God bless you; it cannot be that a child of those tears should perish.” Which words she received as an oracle from Heaven. She was also comforted by a dream, in which she seemed to see a young man, who, having asked the cause of her sorrow and daily tears, bid her be of good courage, for where she was, there her son also was. Upon which she, looking about, saw Augustine standing upon the same plank with herself. This assurance, and her confidence in the divine mercy, gave her present comfort; but she was yet to wait several years for the accomplishment of her earnest desires, and to obtain it by many importunate prayers and tears, which she could not but put forth in abundance, while she saw her beloved son an enemy to that God whom she loved far more than her son or herself. His restless soul soon tired of Thagaste, the provincialism of the place stifled him, and so he went once more to Carthage. There he opened another school of Rhetoric; it was a great success, but being a youth of little over twenty he had need to supplement his knowledge with further reading. Nothing came amiss to this voracious mind; he read anything and everything that came in his way, the classics, the occult sciences, astrology, the fine arts. Meanwhile, more as a practice in dialectic than from any sense of conviction, he set himself to the task of converting his friends to Manicheism, and in part succeeded. At last, again grown restless, and devoured with an ambition for which Carthage had grown too small, he decided to seek his fortune in Rome, the center and capital of the whole world. In spite of his mother’s appeals, in spite of remonstrance from the woman he had ruined but who had been faithful to him, he eluded them both and slipped away, to make a name for himself as a conjurer in words in the heart of the Empire. But the design of God was very different. Augustine’s sojourn in Rome was anything but the success he had anticipated. Scarcely had he arrived when he fell ill, and had to depend on the charity of condescending friends till he recovered, a fact which galled him exceedingly. As soon as he was well, he set about drawing pupils round him; this, in self-occupied, bustling Rome, was a more difficult matter than it had been in Carthage or Thagaste. Moreover the climate and the life of the place began to tell upon him. He could not endure its stifling air, its cobbled and uneven streets, while the coarseness of its manners disgusted this man of the world who, though steeped in vice as much as any Roman, still insisted on refinement. The gluttony and drunkenness he saw everywhere about him, the coarse outcries raised from time to time, in the theaters and elsewhere, against all foreign immigrants, the lack of interest in things intellectual even among those who claimed to be most cultured, the childish imitation, among the rich and so-called upper classes, of eastern splendor and extravagance, the multitudinous temples of all kinds of gods, disgorging every day their besotted votaries — the heart of Rome being eaten out by the serpent of Asia — the contempt for human life, above all for the life of a slave or a captured foe, all these things, in spite of his own depravity, began to tell upon his mind. He was more alone now, and was forced to reflect; his life was in the making and he had to look into the future; if he continued to sin, to his own disgust he found that he did so, not because it satisfied any desire, or because it gave him any pleasure, but because he could not help it. He knew that he was its slave, whatever he might appear, however he might boast of liberty. Long since had Manicheism lost its hold upon him; as he had once used his dialectic in its favor, so now it amused him to tear it to tatters. He clung to it still, for it provided him with a convenient cloak with which to cover and excuse the life which he was at present powerless to check; but in his heart he did not believe in its tenets any longer. Then another force came into his life. Augustine had kept his school open in Rome with no little difficulty, not because he was not successful, but because his pupils would often go away leaving him unpaid. From sheer and undeserved poverty, it seemed he would have to return to Africa. Suddenly a professor’s chair at Milan was offered for competition, and Milan, for many reasons, had come to mean more to Augustine than Rome itself. Milan, not Rome, was now the city of the Emperor and his court; Milan was the center of culture and fashion; above all, it was the home of Ambrose, and Ambrose was a name that was ever on the lips of any master of rhetoric. Augustine competed for the post, and with the help of sundry friends obtained it. He went to Milan; he sought out Ambrose, first to criticize and judge as a master of letters, later to discover a friend. It was not long before, to his own surprise, he was pouring out his now miserable soul into the bishop’s ear. Still that did not come all at once. It would seem that the plain straightforward Roman, though a better scholar, in many ways, than Augustine, never quite understood the eager, melancholy, sensitive and sensuous African, who, nevertheless, was by this time straining for a guide to lead him to the truth. The days passed on into years. The young and ambitious rhetorician had found solid ground at last, and Milan took him to its heart. Great men and wealthy noticed him, invited him to their mansions; Augustine began to tell himself that he could wish for nothing better than to be as one of them. He would settle down, content with that goal; he would marry and become respectable, according to the standard of these men of the world; he would put away the woman he had wronged, and the rest would easily be condoned. He made a first step — and he failed; the ending of one fascination did but open the way to another. He told himself that he could not help but sin; it was part of his nature, his manner of life had made it a necessity. Then why trouble anymore? One day, as he came home from a triumphant speech delivered before the Emperor, drunk with the praises showered on him, an intoxicated man lurched across his path, reveling in coarse merriment. Why should he not live as that man lived? Not it was true, in the same brutish way; but there was a drunkenness that would suit him, which would let him live for the day, without giving the rest a moment’s reflection. Nevertheless, as all this self-questioning showed, a new thing had awakened in him, and he could not make it sleep. He listened to Ambrose when he preached, ostensibly to study him as a rhetorician; he came away forgetting the rhetoric, but with a burning arrow in his heart. More and more he saw what he must do, if he would be even what his own ideal of himself pictured to him; he saw it, but to do it was quite another thing. He listened to the Church’s liturgy; he watched the people at their prayers in full contentment all around him; he longed even to tears that he might be one with them. Still he could not bring himself to pay the price. Let us listen to him here as he tells the story of his conflict at this time. Thus he writes: “O my God, let me with a thankful heart remember and confess to you your mercies on me. Let my very bones be steeped in your love, and let them cry out: ‘Who is like you, Lord?’ (Psalm 35:10). ‘You have broken my bonds asunder; I will offer to You the sacrifice of thanksgiving’ (Psalm 116:16-17). How You have broken them openly I will declare; and all who adore you, when they hear my tale, shall say: ‘Blessed is the Lord, in Heaven and on Earth; great and glorious is His name!’” “The enemy held my will captive; therefore he kept me, chained down and bound. For out of a rebellious will lust had sprung; and lust pampered had become custom; and custom indulged had become necessity. These were the links of the chain; this was the bondage in which I was bound, and that new will which was already born in me, freely to serve You, wholly to enjoy You, God, the only true joy, was not yet able to subdue my former willfulness, strengthened by the wantonness of years. So did my two wills, one new, the other old, one spiritual, the other carnal, fight within me, and by their discord undo my soul.” More and more the truth grew upon him, yet Augustine could not bring himself to act. In a succession of passages he dwells upon his hesitation; they are among the most tragically dramatic pages that he ever wrote. Let us hear some of them. “You did on all sides show me that what You did say was true, and by the truth I was convicted. I had nothing at all to answer but those dull and dreary words: ‘Later, later!’ or ‘Presently!’ or ‘Leave me alone but a little while!’ But my ‘Presently! Presently!’ came to no present, and my ‘Little while!’ lasted long.” “What words did I not use against myself! With scourges of condemnation I lashed my soul, to force it to follow me in my effort to go after You. Yet it drew back; it refused to follow, and without a word of excuse. Its arguments were confuted, its self-defense was spent. There remained no more than mute shrinking; it feared, as it would death itself, to have that disease of habit healed whereby it was wasting to death.” “Thus I lay, soul-sick and tormented, chiding myself more vehemently than ever, rolling and writhing in my bondage, longing for the chain to be wholly broken which alone now held me, but yet did hold me secure. And You, Lord, did oppress me within with Your merciless mercy; You did multiply the lashes of fear and shame, lest I should again give way, and lest I should fail to break this last remaining bond, and it should recover strength, and bind me down the faster. I said within myself: ‘Let it be done at once, let it be done now!’ and, even as I spoke, I all but did it. I all but did it, but I did it not. Still I sank back to my former place; I stood where I was and took breath again. Once more I tried, and wanted somewhat less to make myself succeed, and again somewhat less, and I all but touched and laid hold of the object of my longing; yet again I came not at it, nor touched it, nor laid hold of it. I still recoiled; I would not die to death that I might live to life.” “These petty toys of toys, these vanities of vanities, my longtime fascinations, still held me. They plucked at the garment of my flesh, and murmured caressingly: ‘Are you casting us off? From this moment are we to be with you no more for ever? From this moment shall this delight, or that, be no more lawful for you for ever?’” “The time came when I scarcely heard them. For now they did not openly appear, they did not contradict me; instead they stood as it were behind my back, and muttered their lament, and pulled furtively at my cloak, and begged me, as I stood to go, but to look back on them once more. Thus did their shackles hinder me, and I shrank from shaking myself free from them, that I might burst my bonds and leap forward whither I was called. At the last some habit would whisper in my ear: ‘Do you think that you can live without these things?’” But the liberation came at last. Monica, his mother, had prayed on; she had long since come to Milan to be near her son. She had shared his successes with him, and had even joined in the congratulations, but most of her time had been spent in the church, so much so that she had won the attention of Ambrose the Bishop. One day, on meeting Augustine, he congratulated him on having such a mother. That chance word, it would seem, was the beginning of the last act in the drama. Augustine was flattered with a worthy flattering; he was glad for his mother’s sake and his own, and the love within began to take on a new warmth. On such little things may great destinies depend. And in the meantime, Augustine himself, though continually beaten, did not give up the struggle. If he could not face the hardest ordeal, at least he could do something. One by one he pushed the shackles away; first the bondage that compelled him to live in sin, then that of his false philosophy. Next he ceased to be even by profession a Manichee. Last of all he laid aside his office as municipal orator; it is a proof of the refining process through which he had by this time gone when he tells us that he had grown ashamed of the lies he had to tell for the sake of beautiful language. At length the final grace came, and Augustine received it. “I was tired of devouring time and of being devoured by it,” he writes; he must decide one way or the other. He had come to Milan a skeptic; he had by this time left that far behind. The evidence of a loving and a patient God, the truth of Jesus Christ, the peace and contentment of those who received Him and lived by Him, the summing up of all the philosophers had to say in the teaching of the Bible, the example of great men before him, who had suffered as he now suffered, had seen as he was now beginning to see, had made the leap and had found rest and peace, all these things crowded in upon him, and he knew what he should do. On the other hand was the surrender, the tearing away from all those things, good and evil, which hitherto had made life sweet, or at least as sweet as one like him could ever hope to find it. He could not do it. He despised himself for his hesitation but he could not move. He despised the Roman world which he now knew so well but he could not leave it. Besides, by this time he was ill; he was not himself. To make a change under these conditions was imprudent; when he was well again, he would never be able to persevere, and to fall back, once he had repented, would be only to make his second state worse than the first. He could not decide; even if he decided, it seemed to him that he could not make himself act. He must get someone to help him. He could not go to Ambrose; Ambrose had done for him all he was able and yet so far had failed. There was an old man, Simplicianus; he had been the confessor of Ambrose. In desperation he would go to him. And Simplicianus received him, and humored him; humored him even in his pride, pointing out to him the nobility of truth and sacrifice. There were set before Augustine pictures of St. Antony in the desert and his followers, the hermits of Egypt, who at that time were the talk of Christian Rome. They had surrendered all, yet they were simple men with not much learning. Augustine was in his garden; he thought he was alone. He lay down beneath a tree; his tears wet the ground. “How long?” he cried, “how long shall this be? It is always tomorrow and tomorrow. Why not this hour an end to all my baseness?” As he spoke a little child in a house close by was singing some kind of nursery-rhyme, and the refrain was this “Take up and read, take up and read.” Mechanically Augustine stretched out his hand to a book he had brought with him. It was St. Paul’s Epistles. He took it up, opened it at random, and read: “Put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to satisfy its lusts.” Suddenly all was quiet. He knew his decision had been made, and that he had the power to execute it. There was no more trouble, Augustine rose from where he lay, went into his mother’s room, and there at her feet surrendered his past for ever. Soon he was at the feet of Ambrose, he had been lost and now at last he had found himself. He was at the time just thirty-three years of age. He celebrates his victory in the following passage: “‘O Lord, I am Your servant; I am Your servant and the son of Your handmaid. You have broken my bonds asunder, I will offer to You the sacrifice of praise!’ (Psalm 116:7). ‘Let my heart and my tongue praise You; yes, let all my bones say: “Lord, who is like You?” Let them proclaim it; and do You in return answer me, and say unto my soul : “I am your salvation”’ (Psalm 35:10). Who am I, and what am I? What an evil thing have been my deeds, or if not my deeds my words, or if not my words my will? But You, Lord, are good and merciful, and Your right hand has reached down into the abysmal blackness of my death, and from the bottom of my heart has emptied out its deep of corruption. And Your gift was this, no longer to will what I willed, but to will what You did will. How came it that after all those years, after it was lost in that deep and darksome labyrinth, my free will was called forth in a moment to submit my neck to Your easy yoke, and my shoulders to your light burden, Christ Jesus, my Helper and my Redeemer (Psalm 19:4)? How sweet did it at once become to me to be without the sweetness of those baubles! What I feared to be parted from, it was now a joy to part with. For You did cast them from me, You the true and richest sweetness. You did cast them forth, and in their place did substitute Yourself, sweeter than all delight, though not to flesh and blood, brighter than all light, but more hidden than the lowest deep, higher than all honor, but not to them that are high in their own conceits. Now my soul was free; . . . and my infant tongue spoke to You freely, my light, my riches, my health, the Lord my God.” For the purposes of this study we do not need to follow Augustine too closely through the rest of his career. He was still, to the world about him, the brilliant professor of Milan; only a few of his friends knew of the change that had taken place. He would continue his lectures; there should be no sensation about him. But his health, never strong, had been shaken by the ordeal; it gave him a reason to retire to the villa of a friend at Cassicium, and there for a time he took up his abode. It was a blessed interval. During that period of rest the longing for solitude came over him; a longing which he never lost during all the remainder of his active days. He was still Augustine, the half-pagan; the saint was yet to be formed. The love of argument still delighted him, and that in surroundings that made life on earth most sweet; the comforts of ease, the pleasure of congenial companions, the delight in everything that his eyes could gaze upon. If he laid aside his lectures in Milan, none the less he went on teaching in his new home; but his lessons were drawn from the good things about him, the light in the sky at dawn, the noise of running waters, the goodly warmth of the sun in his veins. By means such as these the natural man was clarified, prepared for the great things that were yet to come. That he might begin again he must leave Milan and Rome, and return to his native Thagaste. On the way his party stopped at Ostia; there took place the memorable scene which he shared with his mother, Monica, when, as he tells us, her conversation led him up to a vision of God he had never known before; there, too, his mother died, and the loss almost broke his heart. He returned to Carthage and thence quickly made his way to Thagaste. Now he could begin in real earnest; and he began as he had learned others had begun before him. His inheritance, now that his mother was dead, he distributed to the poor; for himself, he would turn his house into a monastery, and with his friends, would live a life of prayer, and study, and retirement. But this was not to be. Already he was famous in Thagaste; and there came a day when, as was the manner of those times, the people wanted him to become their priest and he was ordained. As a priest he was sent to Hippo, and there his new career began. He lived a monastic life, but his learning and preaching, first to his own people, then against the heretics about him, made it impossible that he should be hid; soon the cry was raised that he should be the bishop. The rest of his story need not concern us, the rout of the Donatists, who then threatened to dominate northern Africa, the rebuilding of the Church in true poverty of spirit, along with care for the poor, and what we would call the working-classes, the administration of the law which fell upon his shoulders, the incessant preaching and writing, the quantity of which at this time appalls us. We are told that he preached every day, sometimes more than once; often enough, as the words of his sermons indicate, his audience would have him continue till he had to dismiss them for their meals. What concerns us more is the inner soul of the man in the midst of all these labors. For Augustine could never forget what he had been, and the fear never forsook him that with very little he might be the same again. At the time of his consecration as bishop he asked himself with anxiety whether, with his past, and with the scars from that past still upon him, he could face the burden. From time to time old visions would revive and the passions in his soul would leap towards them; even in his old age he trembled to think that some day they might get the better of him. To suppress temptation he would work without ceasing; he would allow himself no respite. When he was not preaching, or helping other souls, he would write; when he was not writing he would pray. When prayer became blank from utter weariness of age still he would pray with a pen in his hand; the only rest he would allow himself was reading, for that, he confesses, was still his delight. By means such as these he kept his other nature down. When we look at the volumes of his works we may assure ourselves that one at least of the motives which produced them was the determination in Augustine’s soul to keep his lower nature in control by incessant labors. Nevertheless labor alone would never have saved or made the Augustine that we know. Living as he was as archbishop in a time of violence, when knives were easily drawn to solve the problems of theology, he had himself often to act with severity. Still the heart of Augustine was an affectionate heart, if in the old days it had led him far astray, in his later life it led him no less to sanctity. While he mercilessly hammered the Donatists about him, at the same time he could address his fellow priests in words like these: “Keep this in mind, my brothers; practice it and preach it with meekness that shall never fail. Love the men you fight, kill only their lie. Rest on truth in all humility; defend it but with no cruelty. Pray for those whom you oppose; pray for them while you correct them.” Yet more than that was his ever increasing hunger after God. In the time of his conversion he shows us how this hunger proved his salvation; then he uttered the memorable sentence by which he is best known: “You have made us, Lord, for Yourself, and our heart shall find no rest till it rests in You.” As the years went on, and as he grew in understanding of this goal of all affection, the hunger was only the more intensified. There is a pathetic scene recorded in his later life, when he gathered his people about him and complained to them that they would not leave him time to pray. With the simplicity of a child he reminded them that this had been part of the bargain when he had become their bishop; it was their part of the bargain and they had not kept it. He asked them, now that he was growing old, to renew their engagement, to permit him to have some days in the week when he might be alone; then they might do with him what they would. They promised; but again the promise was not kept. Circumstances were against him and them; he was living in an age when the old order was being shaken to its foundations, and there was need of a man to build a new world on its ruins. That man was Augustine, and while his eyes and his heart strained after heaven, his intellect and preaching had perforce to attend to the raising of the City of God. But it was just for this purpose that Augustine had been made. He knew the pagan world and depicted it as no man has done from his time till now; the picture he draws is as true today as it was then. And equally true and efficacious is his antidote. As he himself had to grope through his own darkness till he came to God, and then, and then only, saw all in its right perspective, so he told mankind that they would find no solution of their problems in so-called peace, in shirking all restraint, in substituting law for morality, in stifling every voice that ventured to denounce evil-doing, in finding equivocal phrases which seemed to condone all sin. They would find it only where alone it could be found; the world would find no rest till it found it in God. Augustine did not live to see so much as the dawn of the new day which he heralded; on the contrary, his sun went down, and there came over Africa and Hippo the blackest night. As the old man sat in his palace the news was brought to him of the wanton destruction carried out by the Arian Vandals. Nothing was being spared; to this day Northern Africa has not recovered from the scourge. The word vandalism passed into the language of Europe at that time, and has never since been superseded. He heard it all, he appealed to the Roman ruler to defend the right; he was listened to, and then he was betrayed. Still he did not move. With energy he called on his priests to stay with their flocks, and if need be to die with them. At length came the turn for Hippo to be besieged by land and sea. In the third month of the siege Augustine fell ill, probably of one of the fevers which a siege engenders. He grew worse; he knew he was dying; he made a general confession and then, at last, asked that he might be left alone with God. Lying on his bed he heard the din of battle in the distance, and as his mind began to wander he asked himself whether the end of the world had come. But he quickly recovered. No; it was not that. Had not Christ said: “I am with you always, even to the end of the world”? Someday, somehow, the world would be saved. “The Goths won’t take away what Christ keeps guard over!” he told himself, and with this certain hope for mankind he went away to the home he had once described as the place “where we are at rest, where we see as we are seen, where we love and are loved.” It was the fifth day of the Calends of September, August 28th, 430. |

Web Hosting by Just Host