| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

The Greatest and Most Important Week in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

THE ROMAN OCCUPATION AND RULE

OF JUDEA AND JERUSALEM

OF JUDEA AND JERUSALEM

|

The Rise of the Roman Empire

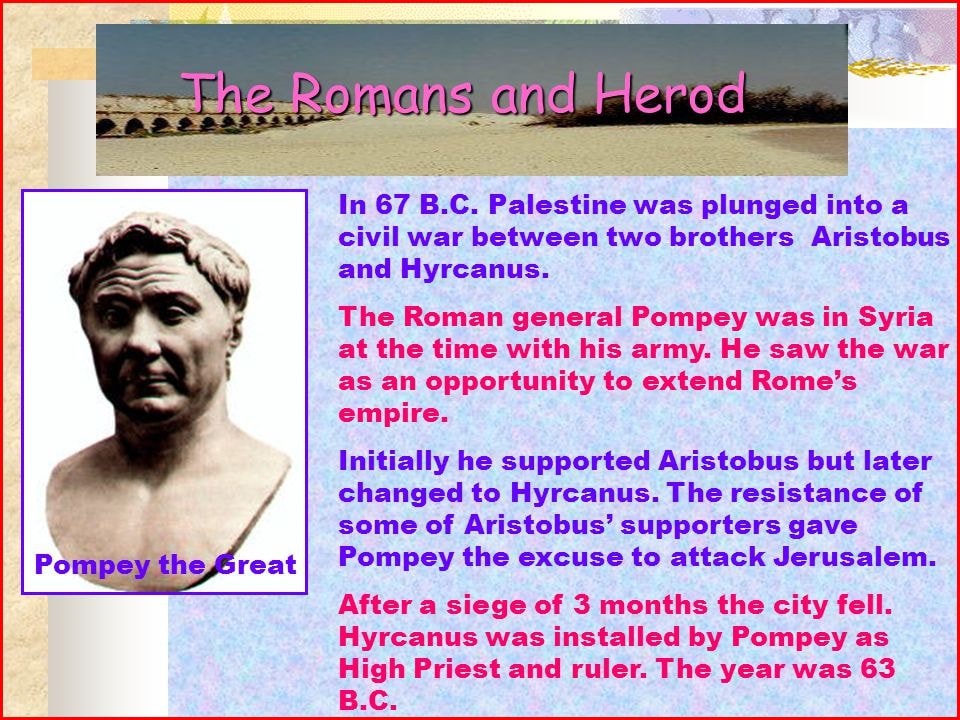

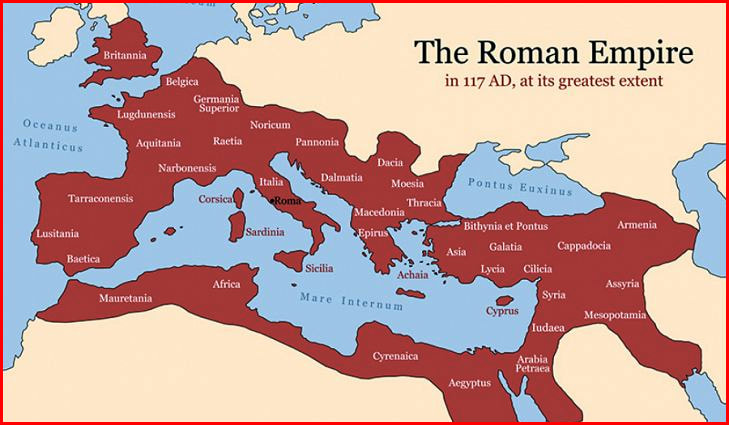

Roman history can be divided into three major periods: (1) the monarchy, traditionally founded in connection with the legend of Romulus and Remus (753 BC), (2) the Roman Republic, established in 509 BC; and (3) the Roman Empire, which sought to bring peace and order to the faltering Republic in 27 BC, and which lasted until its western lands began to fall to Germanic invaders from the north in the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries AD. During the later period of the Roman Republic Rome gained control over the Hellenistic empires surrounding the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Although Rome was unable to extend her control as far eastward as the Persians and the Greeks had, the western part of the empire eventually took in Spain, Gaul (modern France), southern Germany, and southern Britain. Each of the Hellenistic empires was subdivided into Roman provinces in the second and first centuries BC The formation of Syria as a Roman province brought Palestine under Roman control in 63 AD. The vast extension of Roman power over the whole Mediterranean region put an immense strain on the Roman Republic. New tax revenues and interest created an expanded economy, a higher standard of living, and a new wealthy class at Rome. But it also brought political corruption, social dislocation, and moral decline. Political bribery was common; abused slaves on the countryside plantations revolted and were often joined by the oppressed poor. Traditional Roman respect for family gave way to childless marriages, divorce, adultery, prostitution, and pederasty. Exploits abroad created instability at home; a highly centralized, stronger role seemed necessary, and eventually the Romans looked more and more to the military.

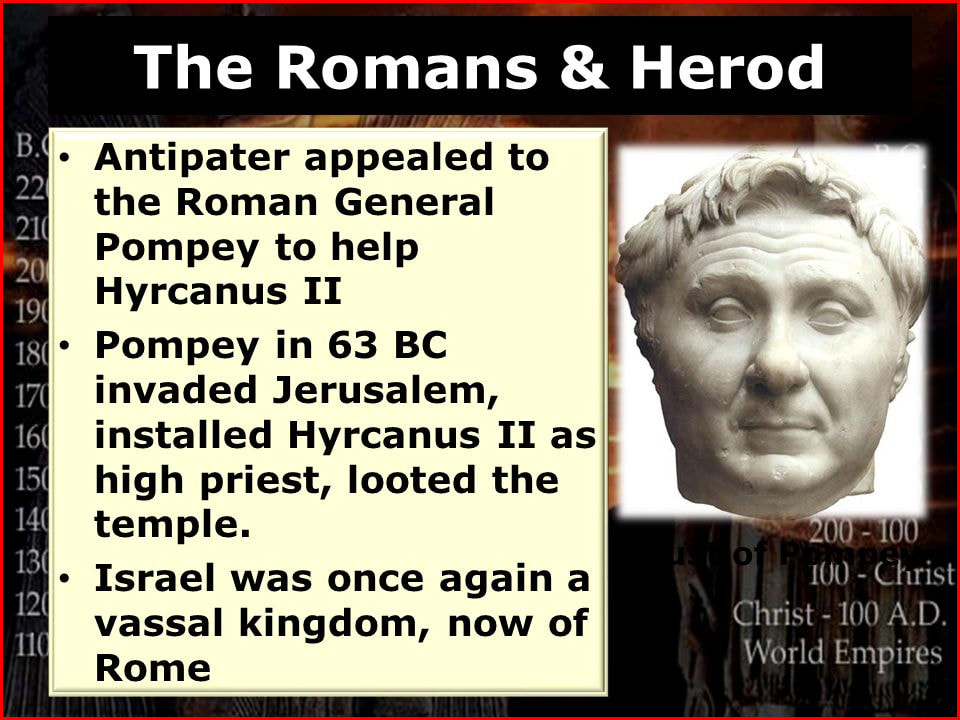

A series of strong leaders emerged in the first century BC, among them Pompey, Julius Caesar, Antony, and Octavian. By 42 BC the armies of Octavian and Antony had decisively defeated those of Caesar’s murderers, leaving Italy and the West in the control of Octavian, and the East as far as the Euphrates in the control of Antony. In 31 BC Octavian’s defeat of Antony’s forces at the battle of Actium, followed by the subsequent suicides of Antony and Cleopatra in Egypt, meant that Octavian was in a position to assume great power. Upon his return to Rome, he was made Imperator, or supreme commander of the army; the Senate conferred upon him the additional titlesAugustus, the August, and Princeps, the first of the Senate. Thus the Roman Empire was born in 27 BC, and Octavian, called Caesar Augustus, was its first emperor.

Augustus was a wise ruler. He secured the borders of the empire and built roads. The result was a new era of peace and stability (the pax Romana). He reorganized the provinces to achieve a more just administration, instituted tax reform, developed a civil service, and engaged in many public works projects, especially in Rome. It was during his reign that Jesus of Nazareth was born. Not all of Augustus’ successors, however, were as capable. Tiberius (14-37 AD), though experienced, was unpopular and spent his last eleven years in a life of debauchery on the island of Capri; one of his infamous appointees was the prefect of Judea, Pontius Pilate. Tiberius was followed by his grandnephew and the great-grandson of Augustus, Gaius Caligula (37-41 AD) who became absorbed with power, demanded that he be addressed as a god, and proposed that his horse be made a consul (he rewarded this animal with a marble stall and a royal purple blanket!). He also drained the treasury to pay for his dissolute life and reckless building activities, and he fomented a crisis among the Jews by demanding that statues of himself be set up in the Temple at Jerusalem. The crisis was averted only when he was assassinated by his private Praetorian Guard. Fortunately, his uncle and successor, Claudius (41-54 AD), though considered weak in body and mind by his relatives, turned out to be a competent ruler. When Claudius was poisoned by his fourth wife Agrippina, Nero (54-68 AD), who was Agrippina’s son by a previous marriage, became emperor. Though at first the empire ran smoothly under the direction of the philosopher Seneca, Nero took control and things began to deteriorate. He poisoned Claudius’ son, executed his own wife, and arranged for the assassination of his mother. There were other murders. In 64 AD a great fire devastated Rome, and Nero found his scapegoat in the Christians. Tradition has it that Peter and Paul were martyred by Nero. Finally, matters got so bad that military commanders seized several provinces and Nero fled the royal palace. Upon hearing that the Senate had condemned him to death “in absentia” (in his absence), the last of the Augustan family rulers committed suicide in 68 AD. Widespread unrest in the empire and chaos at home led to a quick succession of emperors: Galba, Otho, and Vitellius, each military commanders vying for power as the next Emperor. In 69 AD, Vespasian, a seasoned commander who had been dispatched to Palestine to crush a full-scale Jewish revolt that had broken out (66-70 AD) was popularly acclaimed emperor. Vespasian provided a decade of peace and prosperity for the empire (69-79 AD) reminiscent of the Augustan era. Similarly Vespasian’s son and successor, Titus, who had concluded the war with the Jews, reigned wisely for two years (79-81 AD). But a second son of Vespasian, Domitian (81-96 AD), was a tyrant of the first order. He relied on informers, had his enemies murdered, and laid a heavy tax on the people of the empire, especially the Jews. Enamored with his own divinity, he also persecuted the Christians, and it is his reign that provides the backdrop for the most anti-Roman book in the New Testament, the book of Revelation. The following Flavian emperors, as they are called, were some of Rome’s best: Nerva (96-98 AD), Trajan (98-117 AD), Hadrian (117-138 AD), Antonius Plus (138-161 AD), and the Stoic philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180 AD). This brief sketch of the Roman emperors cannot offer a detailed understanding of the period; it can, however, depict the general flavor and tenor of the times, and especially some of the difficulties faced by Jews and Christians. The Arrival of Rome In 63 BC, the Roman general, Pompey, was invited to settle a dispute between two Machabeans. He sided with Hyrcanus II and his supporters, one of whom was Antipater II, the ruler of Idumea. However, from this point forward, Palestine was considered to be controlled by Rome, and, in the reorganization by the Roman Emperor, Augustus, it fell under the administration of the imperial province of Syria. Imperial provinces were governed by a military governor called a “Legate” and Roman troops were stationed to keep order. There were also “districts” that were testy enough to be governed directly by the emperor through his “prefect” (later “procurator”). The chief responsibilities of the governors were civil order, the administration of justice (including the judicial right of life and death), and the collection of taxes. This last responsibility was often farmed out to local tax ‘companies’, whose income was whatever they could collect in excess of the taxes demanded by Rome, which was obviously a system open to abuse. The Roman army―in the legions only Roman citizens were used, in the auxiliary army units local recruits could be used―policed the Roman system of government. The Romans were sensitive enough to permit the Jews some special privileges: exemptions from military service, from going to court on the Sabbath, from being required to portray the emperor’s head on their coins (hence, the need for money changers at the Temple), and from having to offer sacrifices to the emperor as a deity (this being replaced by sacrifices “for Caesar and the Roman nation” twice daily). Furthermore, the Romans were not to represent the image of the emperor on their military standards in areas of heavy Jewish population. Yet, it is also clear that these concessions were not always carried out in practice, and there were a number of occasions when more restless elements in the population resisted Roman abuses and followed the tradition of “zealousness for the Law.” Living conditions were rough. Most people were peasant farmers; there were some artisans; and a few wealthy persons. They lived close to the land, eeking out a living from the earth’s seasonal produce. Most dwelt in small huts, tended a few animals, and had only the barest provisions. Malnutrition was common. Infant mortality was rampant. Government depended on the specific region. Galilee was somewhat autonomous, although some Romans trafficked through there, and the Empire was never far away. Magistrates and other rulers governed this or that city, this or that district. Judea, on the other hand, was administered as a Roman province, so autonomy didn't exist there. The chief priests were the de factorulers of Jerusalem, but they fell under the watchful eye of the Roman prefect (governor) — who was officially, and more supremely, in charge. The people paid taxes to the priesthood and to Caesar. Most of them despised the Roman presence and even the chief priests for their collusion with Rome and their notorious greed. Life in Rome and the Roman Empire The ancient Romans had no such punishment as life in prison. They could have considered housing, feeding, clothing, and giving medical care, at state expense for a person who broke the law, a total waste of public money. Rome, the capital, had over a million people in 100 AD, and only one prison. It was reserved only for important prisoners, such as leaders or kings that were defeated by the Roman army during war. The building would have been dark, damp, smelly, full of rats, and the convicts were chained. They might be tortured regularly and, after the emperor tired of displaying them in public during festivals, they were executed. Many people are astonished that the Roman Empire, with a population at its height of over 35 million people, had many civil laws; such as those regarding property rights, sales of merchandise (slaves, for example, had a warranty), divorce, and policies regarding standard weights and measures. However, they had very few criminal laws, except those regarding patricide as well as incidents involving state security such as treason. The Romans had no police force; people were expected to police themselves. Soldiers were stationed outside the city to keep order because anytime crowds formed, there was always a chance for riots as political unrest was usually just under the surface. Their other responsibility was to serve as the emperor’s bodyguards. Sometimes this did not function well, because if an emperor became unpopular, in some instances, the soldiers killed him themselves. There were also no detectives or investigations of crime by authorities. This meant that, for example, if a man was murdered, it was the responsibility of the eldest male in his immediate or extended family to extract vengeance. This might be in the form of blood money. The murderer’s family would try to scrape together the demanded amount and give it to the victim’s relatives. In cases where money was not desired, or unavailable, the closest male of the murdered victim would thus hunt down and kill the perpetrator. This was what happened when Julius Caesar was killed in 44 BC. In many cases, the criminal would flee the city before this could be carried out; but this too was dangerous. Traveling Roman roads without a large escort was risky. The streets of Rome were extremely crowded and dangerous. If one was wealthy, he would not walk the streets alone, even during the daylight hours. About 40 percent of the population was slave; he would own many and he would have his slaves and his clients surround him and clear the way for safe passage. Even the poor travelled with relatives, and no respectable woman travelled through the city by herself. When Caesar entered the theater with his entourage, on that fateful March day, the 60 co-conspirators cut him off from his retinue, before stabbing him to death. The Senate fled and the most powerful man in Rome lay alone, dead in a pool of blood for two hours, before the fearful senators started to return. In the Roman household, the father, or eldest male, had complete power over the rest of his family. In theory, he could order the death of his wife and children for any reason, with impunity, with slaves being particularly vulnerable. Most of the slaves were captured in war and, in all but a few cases, they would be slaves the rest of their lives as well as any children they might conceive. They were forbidden to marry, were not Roman citizens, and had no rights under Roman law. The best hope a slave could have was to work in the household of a rich Roman who was decent in his treatment. Female slaves could be sexually assaulted at will and, according to surviving historical documents, this was, sadly, often the case. Household slaves could at least sleep in relative comfort and eat the scraps that were left over from their master’s expensive banquets. The worst place a slave could be was to work in the silver mines. There, in three feet of space between ceiling and floor, they toiled 10 hours a day, breathing in the dust. There were no roof supports, so fatalities were common. At night, they slept in chains bound to other slaves. If one slave managed to escape, the others were put to death for allowing it to happen. Punishments for crimes – whether slave or free – were usually carried out in rapid succession. For minor offenses, this might include a severe beating, being flogged or branded on the forehead. More severe crimes might receive a punishment of putting out the eyes, ripping out the tongue, or cutting off ears. The death penalty included being buried alive, impaling and, of course, crucifixion. The Romans did not hesitate to torture before putting someone to death. One such punishment was sewing a bound prisoner in a heavy sack with a snake, a rooster, a monkey and a dog, then throwing the sack into the river. One can only imagine the agony inside. This punishment was usually reserved for patricide, or a son who killed his father. For this reason, almost all Roman homes had bars around the windows and literally barred their doors at night. The streets were unlit and no one ventured out after sundown. In the Bible, Jesus tells the parable of the Good Samaritan who helped the man beaten and robbed, while other passersby ignored him. The Romans understood this all too well, for the incident would not have been unusual. All of this might seem to paint the Romans as being “bad guys”— Romans did enslave, massacre, crucify, hold gladiatorial games, etc. Sure, they weren't very nice by our modern standards. However, in ancient times it wasn't anything special. Saying that Romans were the “bad guys” of the ancient world is an unfair statement. Imperialism? Tell that to the Babylonians, Achaemenids, Persians, Macedonians and many more—who all had massive empires at one time or another in the ancient world. Slavery? I can't think of any major civilization in the ancient world which didn't practice slavery. If anything, some Stoic Romans such as Seneca opposed slavery. Crucifixion? Assyrians skinned people. Greeks had the brazen bull. Vikings had the blood eagle. In fact, the Athenians crucified a Persian general. The Romans reserved crucifixion for escaped slaves, traitors, pirates, generally the worst of the worst. Other nations would crucify thousands lined up in rows that stretched for miles—as an example to the conquered people of what would happen to them if they stepped out of line. Punishments Generally speaking, Roman Citizens were not sentenced to capital punishment if they murdered another Roman Citizen of equal status, but were more often fined or exiled, and if they were executed they were beheaded, which was regarded as a more honorable way to die. If a Roman Citizen killed a slave or any person of lesser status then there was no punishment at all. Protecting the status and position of the Roman Citizens was considered to be a paramount concern and to be stripped of that status was one of the worst punishments imaginable, especially as then you could be subjected to one of the more inventive methods of Roman execution. So public executions were generally events put on to execute slaves who had run away, prisoners of war, common criminals and army deserters, and were regarded as great spectacles and a form or entertainment. The early Christians were also often publicly executed because of their refusal to worship or make sacrifices to the Roman gods or the Emperor. There were special areas set aside in Roman towns for public executions, usually outside the town gates, and also in the same arena where the gladiatorial games took place. Crucifixion in Roman Times Burning alive was another favored form of execution, but perhaps the most shameful way to be executed, in the eyes of a Roman, was to be crucified. Again, you would not suffer this punishment if you were a Roman citizen, which is why St. Paul (being a Roman citizen) was beheaded and St. Peter (not a Roman citizen) was crucified. Crucifixion was carried out in several different ways on different shapes of cross, but generally the prisoners were stripped naked, and either bound or nailed by their wrists to the crossbeam of a wooden cross. This meant that the whole bodyweight of the prisoner was supported only by their arms, which would soon lead to excruciating pain, and often lead to their shoulders and elbow joints dislocating. They would also be unable to breathe properly. It could take several days for a condemned man to die on the cross, and the whole point of the spectacle was that it was to serve as a warning by being so public, prolonged, painful and humiliating. Also the corpse would also be left on the cross to be picked clean by carrion birds, thus ensuring that the unfortunate victim also did not receive an honorable burial. |

Web Hosting by Just Host