| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Daily Thoughts 2025

- Septuagesima

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

-

Spiritual Life

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- Holy Mass Explained

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Scapular

-

Calendar

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

-

Advent Journey

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

- Purgatory

- Precious Blood

- Sacred Heart

- Consecration

- Holy Ghost

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE LINK YOU WISH TO VIEW

| St. Patrick Apostle of Ireland | How the Catholic Faith Came to Ireland | Irish Catholics Come to America |

| St. Patrick Apostle of Ireland | How the Catholic Faith Came to Ireland | Irish Catholics Come to America |

CLICK ON THE SAINT OF YOUR CHOICE

(not all links are activated)

SAINTS WHO WERE MARTYRS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Mary Magdalen | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Dismas the Good Thief | St. Augustine of Hippo |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

OTHER GREAT SAINTS

| St. Patrick |

(not all links are activated)

SAINTS WHO WERE MARTYRS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Mary Magdalen | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Dismas the Good Thief | St. Augustine of Hippo |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

OTHER GREAT SAINTS

| St. Patrick |

ST. PATRICK

APOSTLE & PATRON OF IRELAND

APOSTLE & PATRON OF IRELAND

|

Don't miss out on your St. Patrick's Day HANDOUT and also your St. Patrick's Day POSTER.

The downloads are alongside. |

| ||||||||||||

THE LIFE OF ST. PATRICK

Part 1

From Riches to Rags, From Nobility to Nothing!

Part 1

From Riches to Rags, From Nobility to Nothing!

|

The field of St. Patrick’s labors was the most remote part of the then known world. The seed he planted in faraway Ireland, which, before his time, was largely pagan, bore a rich harvest: whole colonies of saints and missionaries were to rise up after him to serve the Irish Church and to carry Christianity to other lands.

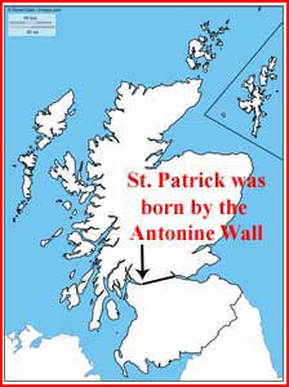

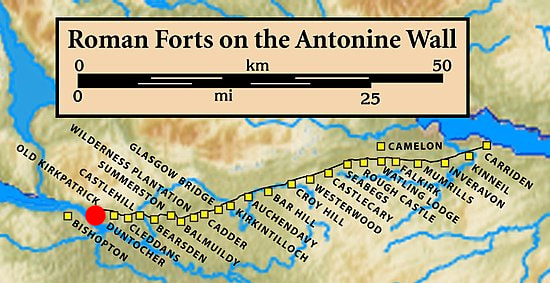

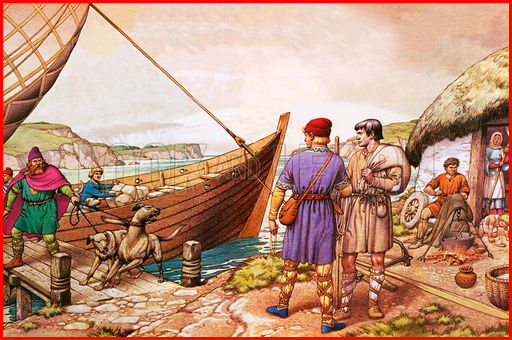

Not Irish—But What Was He? Patrick was not Irish. He was a British Celt, born probably in the area of Dumbarton, Scotland. As with many folk who lived in those early centuries, when records were scarcely kept, there is much dispute among modern scholars about many facets of the life of St. Patrick—his birthplace being one of those points of dispute. Whether his birthplace was a village called Bannavem Taberniae (now called Kilpatrick in honor of St. Patrick), was near Dumbarton-on-the-Clyde in Scotland (which is most common opinion), or in Cumberland, in Northern England, or at the mouth of the River Severn in Southwest England, or even in Gaul, near Boulogne, none of which has never been determined and cannot be determined, none of this really matters, for it is not where he born that is important, but what he did after he was born. Nevertheless, Kilpatrick, near Dumbarton, in Scotland, still retains many memorials of Saint Patrick, and frequent pilgrimages continued far into the Middle Ages to perpetuate there the fame of his sanctity and miracles. “Skilled in War” What we know of a certainty is that Patrick was of Romano-British origin, and born somewhere around 387 to 389. His given name was either Maewyn (Latin: Magonus) or Succat or Sochet (Latin: Sucatus) which, in the Celtic language meant “clever or skilled in war.” It is believed that Pope Celestine renamed him Patricius, after his consecration as a bishop. This evolved into the name Padraig or Patrick that we know him by today. Born into a Noble and Religious Family He had for his parents Cualfarnus (Latin: Calphurnius or Calpurnius) and Conchessa. His father, Cualfarnus, was a deacon in the Catholic Church, his grandfather, Potitus, was a priest, for at this time no strict law of celibacy had been imposed on the Christian clergy. His father also belonged to a Roman family of high rank and held the office of decurio in Gaul or Britain. His mother, Conchessa, was a near relative of the great patron of Gaul (France), St. Martin of Tours. Patrick the Sinner His brief autobiography, Confession (Latin: Confessio], gives us a few details of his early years. At the age of fifteen he committed some sin—what it was we are not told—which caused him much regret and suffering for the rest of his life. At sixteen, he tells us, he still “knew not the true God.” Since he was born into a Christian family, with his father being a deacon and his grandfather a priest, we may take this to mean that he was lukewarm and gave little heed to religion or to the priests. Kidnapped That same year Patrick and some others were seized and carried off by sea raiders to become slaves among the inhabitants of Ireland. It was at this time that the famous Irish King Niall, of the Nine Hostages, was raiding with his Scotti and Pictish allies into Britain and France. In his sixteenth year, Patrick was carried off into captivity by Irish marauders and was sold as a slave to a chieftan, named Milchu, in Dalriada, which was a territory of the present day county of Antrim, in Ireland, where, for six years he tended his slave-master's flocks, in the valley of the Braid and on the slopes of Slemish, near the modern town of Ballymena. Formerly it was believed that his six years of captivity were spent near Ballymena, in County Antrim, on the slopes of the mountain now called Slemish, but later opinion names Fochlad, or Focluth, on the coast of Mayo. If the latter view is correct, then Croachan Aigli or Croag Patrick, the scene of his prolonged fast, was also the mountain on which in his youth he lived alone with God, tending his master’s herds of swine or cattle. There he endured many tribulations, suffering hunger and thirst, cold and nakedness, the work of tending cattle. He had visits from the angel, Victoricus, who was sent to him from God, and there were great miracles which are known to nearly everybody. Adversity Cures Patrick’s Lukewarmness Perhaps the kidnapping and slavery were a punishment from God, or perhaps not—but in any case, the adversity worked wonders for Patrick’s lukewarmness. Finding himself in dire straits, he had to turn to the God and the religion that he had hitherto neglected. Wherever it was that Patrick was enslaved, Patrick himself tells us, in his brief autobiography, Confessions, that “constantly I used to pray in the daytime. Love of God and His fear increased more and more, and my faith grew and my spirit was stirred up, so that in a single day I said as many as a hundred prayers and at night nearly as many, so that whilst in the woods and on the mountain, even before the dawn, I used to wake up to prayer and felt no hurt from it, whether there was snow or ice or rain, nor was there any such slothfulness and lukewarmness in me as now I feel, because then my spirit was fervent within me!” Escape From Captivity In the ways of a benign Providence the six years of Patrick's captivity became an early preparation for his future apostolate in that land. During his captivity, Patrick learned the language and customs of the land. These he added to the Latin that he learned in his youth. He acquired a perfect knowledge of the Celtic tongue in which he would one day convert thousands, announcing the glad tidings of the Gospel of Redemption. Furthermore, since his slave-master, Milchu, was a high priest for the pagan Druids, he became familiar with all the details of Druidism, from whose bondage he was destined to liberate the Irish race. One night, after around six years of slavery, Patrick heard a heavenly voice of an angel, in his dreams, that revealed he would soon return to his homeland. Later on, the voice spoke of a ship, around 200 miles away, that would carry him to Britain. At this point, commanded by the angel, Patrick fled from his cruel master and made his way towards the west. He relates in his “Confessions” that he had to travel about 200 miles on foot; and his journey was probably towards Killala Bay and then onwards to Westport. There he found a ship ready to set sail .The captain at first refused to take him. After Patrick prayed, and, after some insults, rebuffs and mockery, the captain reconsidered and gave him passage and he was eventually allowed on board. They were three days at sea, and when they reached land they traveled for a month through an uninhabited tract and rough terrain of country, where food was scarce. When their food ran out, the ship’s captain challenged Patrick to pray to his God for help. Patrick writes: “And one day the shipmaster said to me: ‘How is this, O Christian? Thou sayest that thy God is great and almighty; wherefore then canst thou not pray for us, for we are in danger of starvation? Likely we shall never see a human being again.’ Then I said plainly to them: ‘Turn in good faith and with all your heart to the Lord my God, to whom nothing is impossible, that this day He may send you food for your journey, until ye be satisfied, for He has abundance everywhere.’ And, by the help of God, so it came to pass. Lo, a herd of swine appeared in the way before our eyes, and they killed many of them. And in that place they remained two nights; and they were well refreshed and their dogs were sated, for many of them had fainted and been left half- dead by the way. After this they rendered hearty thanks to God, and I became honorable in their eyes; and from that day they had food in abundance.” Until Patrick left the seamen a month later, they did not lack for food or anything else. But the holy Patrick tasted naught of this food, for it had been offered in sacrifice to idols; yet he remained unharmed, neither hungry nor thirsty. But while he was asleep the same night, Satan assailed him sorely, fashioning huge rocks, and [with them] crushing his limbs; but he called twice upon Helias; and the sun rose upon him, and with its beams drove away all the mists of darkness, and his strength came back to him. Finally he left their company and in a few days, he was among his friends and family once more in Britain. Second Captivity And again, after many years, he suffered captivity at the hands of foreigners. This time, on the first night, it was vouchsafed to him to hear an answer from God: “For two months thou shalt be with them; that is, with thine enemies.” And so it came to pass; for on the sixtieth day the Lord delivered him out of their hands, and provided for him and his companions, food and fire and shelter, until on the tenth day they reached human habitations. Finally, he found rest, as before, in his own native land with his relatives, who received him as a son; and they entreated him, that after such tribulations and trials, he should never leave them for the rest of his life. But he consented not to this, for many visions were shown to him concerning his future. |

THE LIFE OF ST. PATRICK

Part 2

From Britain to France to Ireland to Work!

Part 2

From Britain to France to Ireland to Work!

Home Again—But Not For Long!

Patrick was about 22 years old when he rejoined his family. They welcomed him warmly, hoping he would never again leave them. But that was not to be. He was among his friends once more in Britain, but now his heart was set on devoting himself to the service of God in the sacred ministry. He soon received dreams that urged him to return to Ireland. “I heard,” he wrote “the voices of those who dwelt beside the wood of Focluth, which is by the western sea. And thus they cried, as if with one mouth: ‘We beg you, holy youth, to come and walk once more among us.’” Patrick understood that God was calling him to take the Gospel to Ireland. In fact, to become the apostle of Ireland.

Off to France to Become and Monk and Priest

Patrick went to France, where he worked for 21 years preparing for his mission. Establishing the Christian Church in Ireland would require many things. He would have to be ready to proclaim the Good News to a pagan people. He would have to be able to provide for the Christian formation and care of his converts. Wherever he founded communities, he would need to recruit and train a native clergy and build and equip churches. Above all, he would have to possess the strength and savvy to overcome the resistance of the druids, the priests who used magic to dominate the Irish.

For three years Patrick devoted himself to acquiring spiritual disciplines and practical skills at the monastery of Lerins. Then he spent fifteen more at Auxerre, where the great monk and bishop St. Germanus was his mentor. Patrick’s training prepared him to be a church planter, not a scholar. Later he keenly felt his lack of education and often bemoaned it. However, he knew that for his task he needed pastoral wisdom more than scholarship. During this time Patrick was ordained a deacon and a priest. Ireland’s first bishop, St. Palladius, died in 431 after only one year of service. Patrick succeeded him as bishop and launched his divinely appointed enterprise in 432.

Sketchy History

Although there is no certainty as to the order of events which followed, it seems likely that Patrick now spent many years in Gaul. Professor Bury, author of the well-known “Life of St. Patrick“, thinks that the saint stayed for three years at the monastery of Lerins, on a small island off the coast of modern Cannes, France, and that about fifteen years were passed at the monastery of Auxerre, where he was ordained. Patrick’s later prestige and authority indicate that he was prepared for his task with great thoroughness.

We meet with him at St. Martin’s monastery at Tours, and again at the island sanctuary of Lérins which was just then acquiring widespread renown for learning and piety; and wherever lessons of heroic perfection in the exercise of Christian life could be acquired, thither the fervent Patrick was sure to bend his steps. No sooner had St. Germanus entered on his great mission at Auxerre than Patrick put himself under his guidance, and it was at that great bishop’s hands that Ireland’s future apostle was a few years later promoted to the priesthood. Patrick’s thoughts turned towards Ireland, and from time to time he was favored with visions of the children from Focluth, by the Western sea, who cried to him: “O holy youth, come back to Erin, and walk once more amongst us.”

Pope St. Celestine entrusted St. Patrick with the mission of gathering the Irish race into the one fold of Christ. Palladius had already received that job, but, terrified by the fierce opposition of an Irish chieftain, had abandoned his work and fled. It was St. Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre, who commended Patrick to the pope. St. Patrick hastened on to Auxerre to make under the guidance of St. Germanus due preparations for the Irish mission. It was probably in the summer months of the year 433, that Patrick and his companions landed at the mouth of the Vantry River close by Wicklow Head.

Now the battle for Ireland was about to start! On the one side was the representative of Jesus Christ and the Catholic Church—St. Patrick! On the other side were the followers of Satan, in the form of Druid priests and pagan kings! Humility versus pride! Meekness versus anger! Heaven versus Hell!

Home Again—But Not For Long!

Patrick was about 22 years old when he rejoined his family. They welcomed him warmly, hoping he would never again leave them. But that was not to be. He was among his friends once more in Britain, but now his heart was set on devoting himself to the service of God in the sacred ministry. He soon received dreams that urged him to return to Ireland. “I heard,” he wrote “the voices of those who dwelt beside the wood of Focluth, which is by the western sea. And thus they cried, as if with one mouth: ‘We beg you, holy youth, to come and walk once more among us.’” Patrick understood that God was calling him to take the Gospel to Ireland. In fact, to become the apostle of Ireland.

Off to France to Become and Monk and Priest

Patrick went to France, where he worked for 21 years preparing for his mission. Establishing the Christian Church in Ireland would require many things. He would have to be ready to proclaim the Good News to a pagan people. He would have to be able to provide for the Christian formation and care of his converts. Wherever he founded communities, he would need to recruit and train a native clergy and build and equip churches. Above all, he would have to possess the strength and savvy to overcome the resistance of the druids, the priests who used magic to dominate the Irish.

For three years Patrick devoted himself to acquiring spiritual disciplines and practical skills at the monastery of Lerins. Then he spent fifteen more at Auxerre, where the great monk and bishop St. Germanus was his mentor. Patrick’s training prepared him to be a church planter, not a scholar. Later he keenly felt his lack of education and often bemoaned it. However, he knew that for his task he needed pastoral wisdom more than scholarship. During this time Patrick was ordained a deacon and a priest. Ireland’s first bishop, St. Palladius, died in 431 after only one year of service. Patrick succeeded him as bishop and launched his divinely appointed enterprise in 432.

Sketchy History

Although there is no certainty as to the order of events which followed, it seems likely that Patrick now spent many years in Gaul. Professor Bury, author of the well-known “Life of St. Patrick“, thinks that the saint stayed for three years at the monastery of Lerins, on a small island off the coast of modern Cannes, France, and that about fifteen years were passed at the monastery of Auxerre, where he was ordained. Patrick’s later prestige and authority indicate that he was prepared for his task with great thoroughness.

We meet with him at St. Martin’s monastery at Tours, and again at the island sanctuary of Lérins which was just then acquiring widespread renown for learning and piety; and wherever lessons of heroic perfection in the exercise of Christian life could be acquired, thither the fervent Patrick was sure to bend his steps. No sooner had St. Germanus entered on his great mission at Auxerre than Patrick put himself under his guidance, and it was at that great bishop’s hands that Ireland’s future apostle was a few years later promoted to the priesthood. Patrick’s thoughts turned towards Ireland, and from time to time he was favored with visions of the children from Focluth, by the Western sea, who cried to him: “O holy youth, come back to Erin, and walk once more amongst us.”

Pope St. Celestine entrusted St. Patrick with the mission of gathering the Irish race into the one fold of Christ. Palladius had already received that job, but, terrified by the fierce opposition of an Irish chieftain, had abandoned his work and fled. It was St. Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre, who commended Patrick to the pope. St. Patrick hastened on to Auxerre to make under the guidance of St. Germanus due preparations for the Irish mission. It was probably in the summer months of the year 433, that Patrick and his companions landed at the mouth of the Vantry River close by Wicklow Head.

Now the battle for Ireland was about to start! On the one side was the representative of Jesus Christ and the Catholic Church—St. Patrick! On the other side were the followers of Satan, in the form of Druid priests and pagan kings! Humility versus pride! Meekness versus anger! Heaven versus Hell!

THE LIFE OF ST. PATRICK

Part 3

The Battle for Ireland! The Conversion of Pagans!

Part 3

The Battle for Ireland! The Conversion of Pagans!

Patrick's Apostolate

We now come to Patrick’s apostolate. At this time Pelagianism was spreading among the weak and scattered Christian communities of Britain and Ireland, and Pope Celestine I had sent Bishop Palladius there to combat it. This missionary was killed among the Scots in North Britain, and Bishop Germanus of Auxerre recommended the appointment of Patrick to replace him.

Patrick was consecrated as a bishop in 432, and departed forthwith for Ireland. When we try to trace the course of his labors in the land of his former captivity, we are confused by the contradictory accounts of his biographers; all are marked by a great deal of vagueness as to geography and chronology. According to tradition, he landed at Inverdea, at the mouth of the river Vautry, and immediately proceeded northwards. One chronicler relates that when he was again in the vicinity of the place where he had been a herdboy, the master who had held him captive, on hearing of Patrick’s return, set fire to his house and perished in the flames.

There is historical basis for the tradition of Patrick’s preliminary stay in Ulster, and his founding of a monastic center there. It was at this time that he set out to gain the support and favor of the powerful pagan King Laeghaire, who was holding court at Tara. The stories of Patrick’s encounter with the king’s Druid priests are probably an accretion of later years; we are told of trials of skill and strength in which the saint gained a great victory over his pagan opponents.

The outcome was royal toleration for his preaching. The text of the Senchus More, the old Irish code of laws, though in its existing form it is of later date, mentions an understanding reached at Tara. Patrick was allowed to preach to the gathering, “and when they saw Laeghaire with his Druids overcome by the great signs and miracles wrought in the presence of the men of Erin, they bowed down in obedience to God and Patrick.”

The Obstacles of the Pagan Druids

King Laeghaire seems not to have become a Christian, but his chief bard and his two daughters were converted, as was a brother, who, we are told, gave his estate to Patrick for the founding of a church. From this time on, Patrick’s apostolate, though carried on amid hardships and often at great risk, was favored by many powerful chieftains. The Druids, by and large, opposed him, for they felt their own power and position threatened. They combined many functions; they were prophets, philosophers, and priests; they served as councilors of kings, as judges, and teachers; they knew the courses of the stars and the properties of plants. Now they began to realize that the religion they represented was doomed.

Even before the Christian missionaries came in strength, a curious prophecy was current among them. It was written in one of their ancient texts: “Adze-head (a name that the shape of the monk’s tonsure might suggest) will come, with his crook-headed staff and his house (the word chasuble means also a little house) holed for his head. He will chant impiety from the table in the east of his house. All his household shall answer: Amen, Amen. When, therefore, all these things come to pass, our kingdom, which is a heathen one, will not stand.”

As a matter of fact, the Druids continued to exist in Christian Ireland, though with a change of name and a limited scope of activity. They subjected Patrick to imprisonment many times, but he always managed to escape.

In 439 three bishops, Secundinus, Auxilius, and Iserninus, were sent from Gaul to assist Patrick. Benignus, an Irish chieftain who was converted by Patrick, became his favorite disciple, his coadjutor in the see of Armagh, and, finally, his successor. One of Patrick’s legendary victories was his overthrow of the idol of Crom Cruach in Leitrim, where he forthwith built a church. He traveled again in Ulster, to preach and found monasteries, then in Leinster and Munster.

These missionary caravans must have impressed the people, for they gave the appearance of an entire village in motion. The long line of chariots and carts drawn by oxen conveyed the items needed for Christian worship, as well as foodstuff, equipment, tools, and weapons required by the band of helpers who accompanied the leader. There would be the priestly assistants, singers and musicians, the drivers, hunters, wood-cutters, carpenters, masons, cooks, horsemen, weavers and embroiderers, and many more.

When the caravan stopped at a chosen site, the people gathered, converts were won, and before many months a chapel or church and its outlying structures would be built and furnished. Thus were created new outposts in the struggle against paganism. The journeys were often dangerous. Once, Odrhan, Patrick’s charioteer, as if forewarned, asked leave to take the chief seat in the chariot himself, while Patrick held the reins; they had proceeded but a short way in this fashion when the loyal Odrhan was killed by a spear thrust meant for his master.

Patrick Goes to Rome

About the year 442, tradition tells us, Patrick went to Rome and met Pope Leo the Great, who, it seemed, took special interest in the Irish Church. The time had now come for a definite organization. According to the annals of Ulster, the cathedral church of Armagh was founded as the primatial see of Ireland on Patrick’s return. He brought back with him valuable relics. Latin was established as the language of the Irish Church. There is mention of a synod held by Patrick, probably at Armagh. The rules then adopted are still preserved, with, possibly, some later interpolations. It is believed that this synod was called near the close of Patrick’s labors on Earth. He was now undoubtedly in more or less broken health; such austerities and constant journeyings as his must have weakened the hardiest constitution.

Patrick's Forty Day Fast

The story of his forty-day fast on Croagh Patrick and the privileges he won from God by his prayers is also associated with the end of his life. Tirechan tells it thus: “Patrick went forth to the summit of Mount Agli, and remained there for forty days and forty nights, and the birds were a trouble to him, and he could not see the face of the heavens, the earth, or the sea, on account of them; for God told all the saints of Erin, past, present, and future, to come to the mountain summit-that mountain which overlooks all others, and is higher than all the mountains of the West-to bless the tribes of Erin, so that Patrick might see the fruit of his labors, for all the choir of the saints came to visit him there, who was the father of them all.”

Defender of the Faith

In all the ancient biographies of this saint the marvelous is continuously present. Fortunately, we have three of Patrick’s own writings, which help us to see the man himself. His Confession is a brief autobiographical sketch; the Lorica, also known as The Song of the Deer, is a strange chant which we have reproduced below. The Letter to Coroticus is a denunciation of the British king of that name, who had raided the Irish coast and killed a number of Christian converts as they were being baptized; Patrick urged the Christian subjects of this king to have no more dealings with him, until he had made reparation for the outrage. In his writings Patrick shows his ardent human feelings and his intense love of God. What was most human in the saint, and at the same time most divine, comes out in this passage from his Confession:

“It was not any grace in me, but God who conquereth in me, and He resisted them all, so that I came to the heathen of Ireland to preach the Gospel and to bear insults from unbelievers, to hear the reproach of my going abroad and to endure many persecutions even unto bonds, the while that I was surrendering my liberty as a man of free condition for the profit of others. And if I should be found worthy, I am ready to give even my life for His name’s sake unfalteringly and gladly, and there (in Ireland) I desire to spend it until I die, if our Lord should grant it to me.”

Magnificently Fruitful Ministry

Patrick’s marvelous harvest filled him with gratitude. During an apostolate of thirty years he is reported to have consecrated some 350 bishops, and was instrumental in bringing the faith to many thousands. He writes, “Wherefore those in Ireland who never had the knowledge of God, but until now only worshiped idols and abominations, from them has been lately prepared a people of the Lord, and they are called children of God. Sons and daughters of Scottish chieftains are seen becoming monks and virgins of Christ.” Yet hostility and violence still existed, for he writes later, “Daily I expect either a violent death, or robbery and a return to slavery, or some other calamity.” He adds, like the good Christian he was, “I have cast myself into the hands of Almighty God, for He rules everything.”

Patrick died about 461, and was buried near the fortress of Saul, in the vicinity of the future cathedral town of Down. He was intensely spiritual, a magnetic personality with great gifts for action and organization. He brought Ireland into much closer contact with Europe, especially with the Holy See. The building up of the weak Christian communities which he found on arrival and planting the faith in new regions give him his place as the patron of Ireland. His feast day is one of festivity, and widely observed. Patrick’s emblems are a serpent, demons, cross, shamrock, harp, and baptismal font. The story of his driving snakes from Ireland has no factual foundation, and the tale of the shamrock, as a symbol used to explain the Trinity, is an accretion of much later date.

Lorica―St. Patrick’s Breastplate

The Latin word lorica means a breastplate. Chants like the one below, almost in the form of incantations, or invocations of God and Christ, to protect the singer against the wiles of evil man, are not uncommon in early Irish literature.

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through a belief in the threeness,

Through a confession of the oneness

Of the Creator of Creation.

I arise today

Through the strength of Christ’s birth with His Baptism,

Through the strength of His crucifixion with His burial,

Through the strength of His resurrection with His ascension,

Through the strength of His descent for the judgment of Doom.

I arise today

Through the strength of the love of Cherubim,

In obedience of angels, In the service of archangels,

In hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

In prayers of patriarchs In predictions of prophets,

In preachings of apostles, In faiths of confessors,

In innocence of holy virgins, In deeds of righteous men.

I arise today

Through the strength of Heaven:

Light of sun

Radiance of moon,

Splendor of fire,

Speed of lightning,

Swiftness of wind,

Depth of sea,

Stability of earth,

Firmness of rock.

I arise today

Through God’s strength to pilot me:

God’s might to uphold me,

God’s wisdom to guide me,

God’s eye to look before me,

God’s ear to hear me,

God’s word to speak for me,

God’s hand to guard me,

God’s way to lie before me,

God’s shield to protect me,

God’s host to save me

From snares of devils,

From temptations of vices,

From everyone who shall wish me ill,

Afar and anear,

Alone and in a multitude.

I summon today all these powers between me and those evils,

Against every cruel merciless power that may oppose my body and soul,

Against incantations of false prophets,

Against black laws of pagandom,

Against false laws of heretics,

Against craft of idolatry,

Against spells of women and smiths and wizards,

Against every knowledge that corrupts man’s body and soul.

Christ shield me today

Against poison, against burning,

Against drowning, against wounding,

So that there may come to me abundance of reward,

Christ with me,

Christ before me,

Christ behind me,

Christ in me,

Christ beneath me,

Christ above me,

Christ on my right,

Christ on my left,

Christ when I lie down,

Christ when I sit down,

Christ when I arise,

Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me, Christ in every ear that hears me.

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through a belief in the threeness,

Through a confession of the oneness

Of the Creator of Creation.

We now come to Patrick’s apostolate. At this time Pelagianism was spreading among the weak and scattered Christian communities of Britain and Ireland, and Pope Celestine I had sent Bishop Palladius there to combat it. This missionary was killed among the Scots in North Britain, and Bishop Germanus of Auxerre recommended the appointment of Patrick to replace him.

Patrick was consecrated as a bishop in 432, and departed forthwith for Ireland. When we try to trace the course of his labors in the land of his former captivity, we are confused by the contradictory accounts of his biographers; all are marked by a great deal of vagueness as to geography and chronology. According to tradition, he landed at Inverdea, at the mouth of the river Vautry, and immediately proceeded northwards. One chronicler relates that when he was again in the vicinity of the place where he had been a herdboy, the master who had held him captive, on hearing of Patrick’s return, set fire to his house and perished in the flames.

There is historical basis for the tradition of Patrick’s preliminary stay in Ulster, and his founding of a monastic center there. It was at this time that he set out to gain the support and favor of the powerful pagan King Laeghaire, who was holding court at Tara. The stories of Patrick’s encounter with the king’s Druid priests are probably an accretion of later years; we are told of trials of skill and strength in which the saint gained a great victory over his pagan opponents.

The outcome was royal toleration for his preaching. The text of the Senchus More, the old Irish code of laws, though in its existing form it is of later date, mentions an understanding reached at Tara. Patrick was allowed to preach to the gathering, “and when they saw Laeghaire with his Druids overcome by the great signs and miracles wrought in the presence of the men of Erin, they bowed down in obedience to God and Patrick.”

The Obstacles of the Pagan Druids

King Laeghaire seems not to have become a Christian, but his chief bard and his two daughters were converted, as was a brother, who, we are told, gave his estate to Patrick for the founding of a church. From this time on, Patrick’s apostolate, though carried on amid hardships and often at great risk, was favored by many powerful chieftains. The Druids, by and large, opposed him, for they felt their own power and position threatened. They combined many functions; they were prophets, philosophers, and priests; they served as councilors of kings, as judges, and teachers; they knew the courses of the stars and the properties of plants. Now they began to realize that the religion they represented was doomed.

Even before the Christian missionaries came in strength, a curious prophecy was current among them. It was written in one of their ancient texts: “Adze-head (a name that the shape of the monk’s tonsure might suggest) will come, with his crook-headed staff and his house (the word chasuble means also a little house) holed for his head. He will chant impiety from the table in the east of his house. All his household shall answer: Amen, Amen. When, therefore, all these things come to pass, our kingdom, which is a heathen one, will not stand.”

As a matter of fact, the Druids continued to exist in Christian Ireland, though with a change of name and a limited scope of activity. They subjected Patrick to imprisonment many times, but he always managed to escape.

In 439 three bishops, Secundinus, Auxilius, and Iserninus, were sent from Gaul to assist Patrick. Benignus, an Irish chieftain who was converted by Patrick, became his favorite disciple, his coadjutor in the see of Armagh, and, finally, his successor. One of Patrick’s legendary victories was his overthrow of the idol of Crom Cruach in Leitrim, where he forthwith built a church. He traveled again in Ulster, to preach and found monasteries, then in Leinster and Munster.

These missionary caravans must have impressed the people, for they gave the appearance of an entire village in motion. The long line of chariots and carts drawn by oxen conveyed the items needed for Christian worship, as well as foodstuff, equipment, tools, and weapons required by the band of helpers who accompanied the leader. There would be the priestly assistants, singers and musicians, the drivers, hunters, wood-cutters, carpenters, masons, cooks, horsemen, weavers and embroiderers, and many more.

When the caravan stopped at a chosen site, the people gathered, converts were won, and before many months a chapel or church and its outlying structures would be built and furnished. Thus were created new outposts in the struggle against paganism. The journeys were often dangerous. Once, Odrhan, Patrick’s charioteer, as if forewarned, asked leave to take the chief seat in the chariot himself, while Patrick held the reins; they had proceeded but a short way in this fashion when the loyal Odrhan was killed by a spear thrust meant for his master.

Patrick Goes to Rome

About the year 442, tradition tells us, Patrick went to Rome and met Pope Leo the Great, who, it seemed, took special interest in the Irish Church. The time had now come for a definite organization. According to the annals of Ulster, the cathedral church of Armagh was founded as the primatial see of Ireland on Patrick’s return. He brought back with him valuable relics. Latin was established as the language of the Irish Church. There is mention of a synod held by Patrick, probably at Armagh. The rules then adopted are still preserved, with, possibly, some later interpolations. It is believed that this synod was called near the close of Patrick’s labors on Earth. He was now undoubtedly in more or less broken health; such austerities and constant journeyings as his must have weakened the hardiest constitution.

Patrick's Forty Day Fast

The story of his forty-day fast on Croagh Patrick and the privileges he won from God by his prayers is also associated with the end of his life. Tirechan tells it thus: “Patrick went forth to the summit of Mount Agli, and remained there for forty days and forty nights, and the birds were a trouble to him, and he could not see the face of the heavens, the earth, or the sea, on account of them; for God told all the saints of Erin, past, present, and future, to come to the mountain summit-that mountain which overlooks all others, and is higher than all the mountains of the West-to bless the tribes of Erin, so that Patrick might see the fruit of his labors, for all the choir of the saints came to visit him there, who was the father of them all.”

Defender of the Faith

In all the ancient biographies of this saint the marvelous is continuously present. Fortunately, we have three of Patrick’s own writings, which help us to see the man himself. His Confession is a brief autobiographical sketch; the Lorica, also known as The Song of the Deer, is a strange chant which we have reproduced below. The Letter to Coroticus is a denunciation of the British king of that name, who had raided the Irish coast and killed a number of Christian converts as they were being baptized; Patrick urged the Christian subjects of this king to have no more dealings with him, until he had made reparation for the outrage. In his writings Patrick shows his ardent human feelings and his intense love of God. What was most human in the saint, and at the same time most divine, comes out in this passage from his Confession:

“It was not any grace in me, but God who conquereth in me, and He resisted them all, so that I came to the heathen of Ireland to preach the Gospel and to bear insults from unbelievers, to hear the reproach of my going abroad and to endure many persecutions even unto bonds, the while that I was surrendering my liberty as a man of free condition for the profit of others. And if I should be found worthy, I am ready to give even my life for His name’s sake unfalteringly and gladly, and there (in Ireland) I desire to spend it until I die, if our Lord should grant it to me.”

Magnificently Fruitful Ministry

Patrick’s marvelous harvest filled him with gratitude. During an apostolate of thirty years he is reported to have consecrated some 350 bishops, and was instrumental in bringing the faith to many thousands. He writes, “Wherefore those in Ireland who never had the knowledge of God, but until now only worshiped idols and abominations, from them has been lately prepared a people of the Lord, and they are called children of God. Sons and daughters of Scottish chieftains are seen becoming monks and virgins of Christ.” Yet hostility and violence still existed, for he writes later, “Daily I expect either a violent death, or robbery and a return to slavery, or some other calamity.” He adds, like the good Christian he was, “I have cast myself into the hands of Almighty God, for He rules everything.”

Patrick died about 461, and was buried near the fortress of Saul, in the vicinity of the future cathedral town of Down. He was intensely spiritual, a magnetic personality with great gifts for action and organization. He brought Ireland into much closer contact with Europe, especially with the Holy See. The building up of the weak Christian communities which he found on arrival and planting the faith in new regions give him his place as the patron of Ireland. His feast day is one of festivity, and widely observed. Patrick’s emblems are a serpent, demons, cross, shamrock, harp, and baptismal font. The story of his driving snakes from Ireland has no factual foundation, and the tale of the shamrock, as a symbol used to explain the Trinity, is an accretion of much later date.

Lorica―St. Patrick’s Breastplate

The Latin word lorica means a breastplate. Chants like the one below, almost in the form of incantations, or invocations of God and Christ, to protect the singer against the wiles of evil man, are not uncommon in early Irish literature.

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through a belief in the threeness,

Through a confession of the oneness

Of the Creator of Creation.

I arise today

Through the strength of Christ’s birth with His Baptism,

Through the strength of His crucifixion with His burial,

Through the strength of His resurrection with His ascension,

Through the strength of His descent for the judgment of Doom.

I arise today

Through the strength of the love of Cherubim,

In obedience of angels, In the service of archangels,

In hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

In prayers of patriarchs In predictions of prophets,

In preachings of apostles, In faiths of confessors,

In innocence of holy virgins, In deeds of righteous men.

I arise today

Through the strength of Heaven:

Light of sun

Radiance of moon,

Splendor of fire,

Speed of lightning,

Swiftness of wind,

Depth of sea,

Stability of earth,

Firmness of rock.

I arise today

Through God’s strength to pilot me:

God’s might to uphold me,

God’s wisdom to guide me,

God’s eye to look before me,

God’s ear to hear me,

God’s word to speak for me,

God’s hand to guard me,

God’s way to lie before me,

God’s shield to protect me,

God’s host to save me

From snares of devils,

From temptations of vices,

From everyone who shall wish me ill,

Afar and anear,

Alone and in a multitude.

I summon today all these powers between me and those evils,

Against every cruel merciless power that may oppose my body and soul,

Against incantations of false prophets,

Against black laws of pagandom,

Against false laws of heretics,

Against craft of idolatry,

Against spells of women and smiths and wizards,

Against every knowledge that corrupts man’s body and soul.

Christ shield me today

Against poison, against burning,

Against drowning, against wounding,

So that there may come to me abundance of reward,

Christ with me,

Christ before me,

Christ behind me,

Christ in me,

Christ beneath me,

Christ above me,

Christ on my right,

Christ on my left,

Christ when I lie down,

Christ when I sit down,

Christ when I arise,

Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me, Christ in every ear that hears me.

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through a belief in the threeness,

Through a confession of the oneness

Of the Creator of Creation.

THE LIFE OF ST. PATRICK

Part 4

St. Patrick's Legacy!

Part 4

St. Patrick's Legacy!

Patrick died in Ireland and is traditionally believed to be buried on the Hill of Down in Downpatrick, in county Down. A stone marking the traditional burial spot was added in 1901 and the site is now a popular tourist attraction.

The Rise of Monasticism

The churches set up by Patrick and other missionaries were fairly simple affairs. During the late 400s, hundreds of churches were set up. They were unlike the churches that we would recognize today: most were small wooden buildings, with the occasional small stone structure and would not have accommodated more than a few dozen people at a time. Each tuath (petty kingdom) had a ‘bishop’ to oversee the church’s work in it.

In time, the Irish Church matured and by the 500s a number of monasteries were set up. Initially intended to be places of retreat from the world, they attracted the patronage of the kings and the rich and became influential institutions in their own right. Many extended control over other monasteries, with Armagh ultimately claiming primacy over all churches in Ireland. The network of buildings that eventually grew up on monastic settlements ― the hired workers, craftsmen and artisans ― were, in a sense, the first ‘towns’ in Ireland.

A Celtic monastery was not of the church-and-cloisters type that appeared in the Middle Ages. Rather, it usually consisted of an enclosure with a small stone church and a number of cells were the monks lived individually. By their nature, some were in the most remote areas imaginable. Sceilg Mhicil was perched on an outcrop of rock in the stormy north Atlantic off the coast of county Kerry. Many monasteries were set up in connection with the ministry of Patrick, for example the great monastery of Armagh.

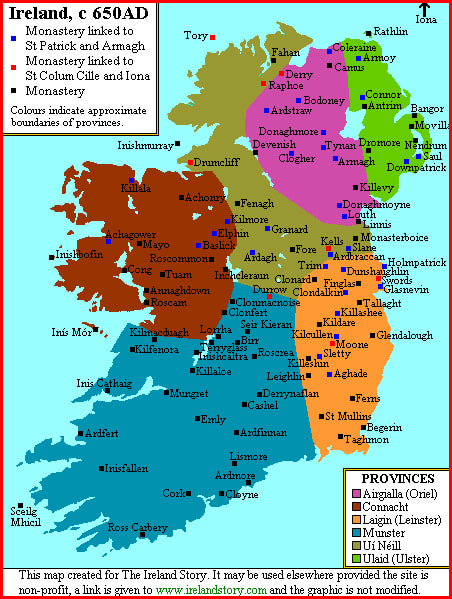

One of the most prominent Irish Saints was St. Colum Cille (also known as St. Columba and St. Colmcille). Colum Cille was of the province of the northern Uí Néill (in present-day Donegal), a prominent relative of the King who became a Christian and evangelized in the Irish colony of the Dal Riata in Scotland. Colum Cille believed in people becoming “Exiles for Christ”, by leaving their homes to go and live with other Christians in isolated places, thereby coming closer to God. He set up monasteries in Ireland, such as that at Derry, before setting up the monastery of Iona off the western Scottish coast in the year 563. Colum Cille’s establishment successfully converted the Dal Riata before converting Northumbria [Northern England] by 627. The great Northumbrian monastery of Lindisfarne was founded in 635. Thus, Britian was Christianized by a missionary from north-west Ireland. Iona and Armagh together became the most influential monasteries in Ireland. The map below shows the principal monasteries in Ireland as they were around the year 650 [5].

The Irish Church was fairly simple, because the hierarchical structure of the continental Church was found to be incompatible with the network of small kingdoms in Ireland. However, Roman missionaries had arrived in southern England and there were disagreements between the Celtic Church and the Roman Church. This was resolved at the Synod of Whitby of 664, in which it was decided that the Church in Britain would follow the Roman practices. However, the people in Ireland resisted the changes and so Romanism did not have much impact in Ireland.

The Rise of Monasticism

The churches set up by Patrick and other missionaries were fairly simple affairs. During the late 400s, hundreds of churches were set up. They were unlike the churches that we would recognize today: most were small wooden buildings, with the occasional small stone structure and would not have accommodated more than a few dozen people at a time. Each tuath (petty kingdom) had a ‘bishop’ to oversee the church’s work in it.

In time, the Irish Church matured and by the 500s a number of monasteries were set up. Initially intended to be places of retreat from the world, they attracted the patronage of the kings and the rich and became influential institutions in their own right. Many extended control over other monasteries, with Armagh ultimately claiming primacy over all churches in Ireland. The network of buildings that eventually grew up on monastic settlements ― the hired workers, craftsmen and artisans ― were, in a sense, the first ‘towns’ in Ireland.

A Celtic monastery was not of the church-and-cloisters type that appeared in the Middle Ages. Rather, it usually consisted of an enclosure with a small stone church and a number of cells were the monks lived individually. By their nature, some were in the most remote areas imaginable. Sceilg Mhicil was perched on an outcrop of rock in the stormy north Atlantic off the coast of county Kerry. Many monasteries were set up in connection with the ministry of Patrick, for example the great monastery of Armagh.

One of the most prominent Irish Saints was St. Colum Cille (also known as St. Columba and St. Colmcille). Colum Cille was of the province of the northern Uí Néill (in present-day Donegal), a prominent relative of the King who became a Christian and evangelized in the Irish colony of the Dal Riata in Scotland. Colum Cille believed in people becoming “Exiles for Christ”, by leaving their homes to go and live with other Christians in isolated places, thereby coming closer to God. He set up monasteries in Ireland, such as that at Derry, before setting up the monastery of Iona off the western Scottish coast in the year 563. Colum Cille’s establishment successfully converted the Dal Riata before converting Northumbria [Northern England] by 627. The great Northumbrian monastery of Lindisfarne was founded in 635. Thus, Britian was Christianized by a missionary from north-west Ireland. Iona and Armagh together became the most influential monasteries in Ireland. The map below shows the principal monasteries in Ireland as they were around the year 650 [5].

The Irish Church was fairly simple, because the hierarchical structure of the continental Church was found to be incompatible with the network of small kingdoms in Ireland. However, Roman missionaries had arrived in southern England and there were disagreements between the Celtic Church and the Roman Church. This was resolved at the Synod of Whitby of 664, in which it was decided that the Church in Britain would follow the Roman practices. However, the people in Ireland resisted the changes and so Romanism did not have much impact in Ireland.

|

One of the most important works of the Irish monasteries, besides catering for the needs of the local population, was in the production of books. These are the great illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells, which were hand written copies of the Bible and other books. Beautifully decorated by hand, these books were usually written in Latin, which was introduced by Patrick. The Latin alphabet was also introduced, replacing the more awkward Ogham scripts. Although Latin was the language of education, Celtic-Irish remained the language of everyday life.

Irish Influences in Europe As Ireland’s monastic establishments grew, they became centers of learning as well as of evangelism. It is for this reason that Ireland has been termed the land of “Saints and Scholars”. After Colum Cille, and his evangelical successor Aidan, had set up the monasteries in Scotland and Northumbria (northern England), the Irish turned their attention to southern England. St. Fursa preached in East Anglia (eastern England) in the 6th century, before travelling to Gaul (France) and setting up churches there. St. Columbanus, of Bangor Monastery in northern Ireland, went to Gaul in 591 and founded two monasteries in France, before travelling through modern Germany, Switzerland and Italy. He is buried in a Monastery he founded at Bobbio, in northern Italy. By the 9th century, Irish scholars followed the missionaries and managed to gain important academic roles in the courts of Kings such as Charlemagne of the Franks. Irish foundations can be found in France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Italy and their influence was been left in places as far afield as Vienna, Rome and eastern Germany. Dynastic Changes Of course, all through the early Christian period, the dynastic quarrels between the Celtic kings of Ireland continued. The Provinces were groups of kings who had submitted their tuath (petty kingdom) to the authority of one of the other kings. This king was the king of the province. Around the time of St. Patrick, the Ulaid ruled must of Northern Ireland, Munster was in the south, Laigin was in the south-east and Connacht was in the west. The Uí Néill ruled an area from central-eastern Ireland to the north-western corner. |

The southern Uí Néill spent the early Christian period expanding eastwards at the expense of Laigin. The power of the Ulaid, whose capital was at Emain Macha (near Armagh), was slowly diminished by the “Three Collas” who drove them out of their western lands and set up the Province of Airgialla (also known as Oriel). Airgialla eventually captured Emain Macha. In response to being driven eastwards, some of the Ulaid founded a colony in Scotland. This is the colony of the Dal Riata.

By the early 700s, the spread of Christianity and continued growth of the concept of a ‘province’ meant that the Kings of individual tuaths ceased to be regarded as kings, and were referred to increasingly as dukes or lords. The provinces evolved from being federations of dozens of tuaths, to being more closely knit units whose king was from one of the more prominent families. It became more common, then, for there to be dynastic disputes within provinces over which family held the kingship. A province can be almost regarded as an independent country, although without the well-delineated borders of today.

The period 700-850 marks the growth in the influence of the Uí Néill. Their northern half was dominated by the Cenel nEoghan dynasty, who lived in the east of the territory and they went on the offensive against the province of Airgialla, driving them out of their northern territories over the century 750-850. By 804, the Uí Néill had become the protectors of the monastery of Armagh. Meanwhile, the southern Uí Néill penetrated further into Laigin in the period 700-800, driving them out of the Boyne valley and taking control of the royal site of Tara.

In the 700s, the power of Connaght rose dramatically, and they began to expand eastwards, further dividing the northern and southern Uí Néill and founding the secondary province of Bréifne around present-day Cavan and Leitrim. This had the additional effect of splitting the Uí Néill into two parts, referred to simply as the Northern Uí Néill and the Southern Uí Néill.

It was around about this time that the kings of Ireland began to realize that it might be possible to extend control over the entire island ― a concept not previously considered. This gave rise to the term High King and, although nobody could yet legitimately use the term, it did not stop the Uí Néill eyeing it up.

By the early 700s, the spread of Christianity and continued growth of the concept of a ‘province’ meant that the Kings of individual tuaths ceased to be regarded as kings, and were referred to increasingly as dukes or lords. The provinces evolved from being federations of dozens of tuaths, to being more closely knit units whose king was from one of the more prominent families. It became more common, then, for there to be dynastic disputes within provinces over which family held the kingship. A province can be almost regarded as an independent country, although without the well-delineated borders of today.

The period 700-850 marks the growth in the influence of the Uí Néill. Their northern half was dominated by the Cenel nEoghan dynasty, who lived in the east of the territory and they went on the offensive against the province of Airgialla, driving them out of their northern territories over the century 750-850. By 804, the Uí Néill had become the protectors of the monastery of Armagh. Meanwhile, the southern Uí Néill penetrated further into Laigin in the period 700-800, driving them out of the Boyne valley and taking control of the royal site of Tara.

In the 700s, the power of Connaght rose dramatically, and they began to expand eastwards, further dividing the northern and southern Uí Néill and founding the secondary province of Bréifne around present-day Cavan and Leitrim. This had the additional effect of splitting the Uí Néill into two parts, referred to simply as the Northern Uí Néill and the Southern Uí Néill.

It was around about this time that the kings of Ireland began to realize that it might be possible to extend control over the entire island ― a concept not previously considered. This gave rise to the term High King and, although nobody could yet legitimately use the term, it did not stop the Uí Néill eyeing it up.

Web Hosting by Just Host