| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

- Sacred Heart

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Holy Ghost

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

CLICK ON THE NAME OF THE SAINT YOU WISH TO VIEW

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

(not all links are activated at this time)

THE ROMAN MARTYROLOGY FOR EACH MONTH OF THE YEAR

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | All 365 Days on One Page |

MARTYRED SAINTS

| Your Daily Martyr | The Age of Martyrdom (20th & 21st centuries) | The School of Martyrdom | St. Peter the Apostle | St. Paul of Tarsus | St. James the Great |

| St. Andrew | St. John the Baptist | The North American Martyrs | St. Christina | St. Afra | The Seven Holy Sleepers | The Cristeros of Mexico |

SAINTS OF MARY

| St. Louis-Marie de Montfort | St. Dominic | St. John Eudes | St. Maximilian Kolbe | St. Bernard | St. Alphonsus Liguori | St. Ephrem |

| St. Catherine Laboure | St. Bernadette | St. Bridget | St. Catherine of Siena | Pope St. Pius X |

DESERT SAINTS

| Saints of the Desert | St. Paul the Hermit | St. Anthony of Egypt | Desert Father Wisdom |

SAINTS FOR SINNERS

| St. Paul of Tarsus | St. Augustine | St. Mary Magdalen | Dismas the Good Thief |

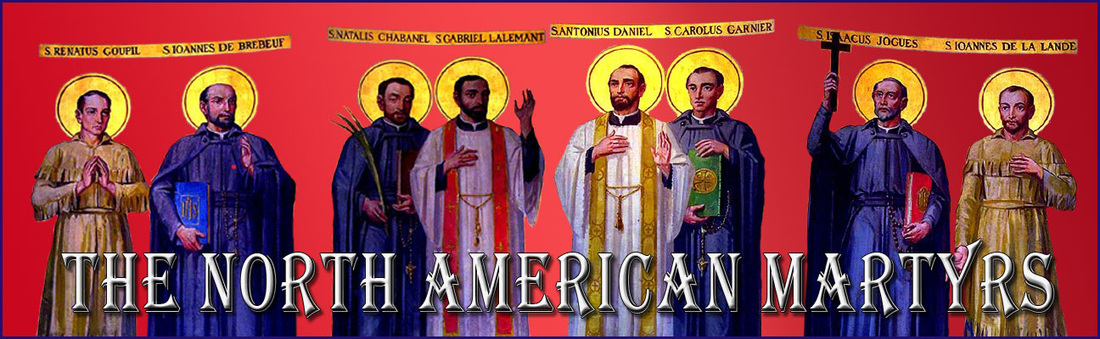

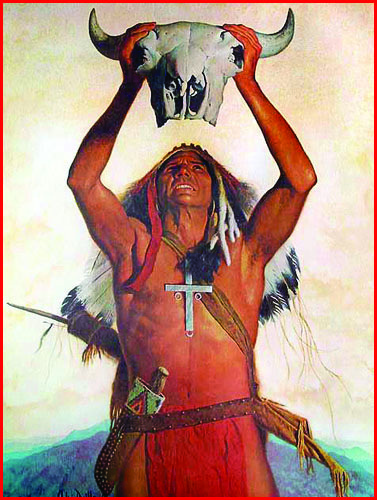

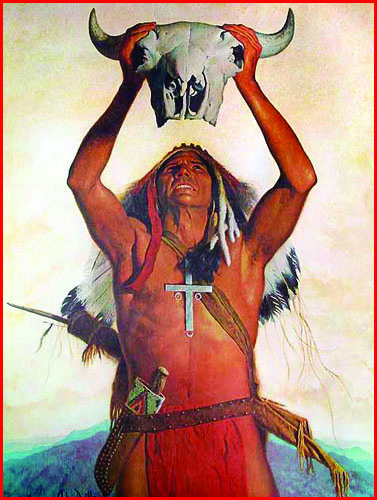

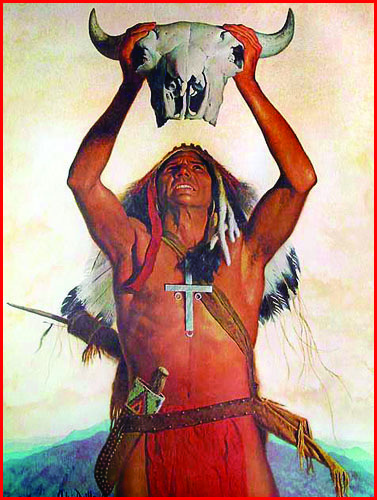

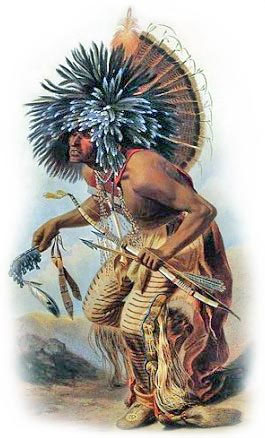

Their feast day is celebrated on September 26th in Canada and among traditional Roman Catholics. The feast day is celebrated on October 19th in the United States under the title of "The North American Martyrs." Below you will find a series of articles examining their lives and their heroism in resisting paganism and trying to bring the Faith to the North American continent. In our current times of ease and comfort, they are a beacon for the Faith, who show us an example of a deep love of God that forsakes ease and comfort and endures some of the most trying and most horrific tortures brought on by man, beast and nature. The first article is merely a roll-call, so to speak, or a listing of the cast, in what was to be an epic battle for the Faith on these shores. The successive articles enter more deeply into the particular struggles and sufferings undergone at the hands of the Indians they were trying so valiantly to convert.

THE EIGHT NORTH AMERICAN MARTYRS (Part 1)

|

OUR SOURCES OF KNOWLEDGE

The chief source of our knowledge of the life, customs, and languages of the Indians, and of the works and lives of the missionaries, colonists, traders, and others who entered upon the stage of New France from 1610 to 1672, is the letters and reports which the Jesuit missionaries sent to their superiors in France and Rome.

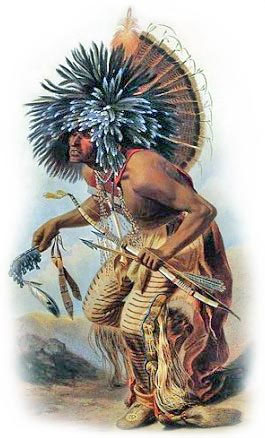

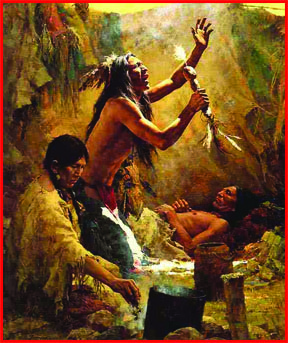

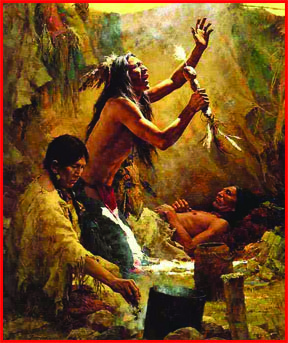

These letters and reports were published in a series of seventy-three volumes under the title The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, which have won unstinted praise from scholars throughout the world as a monumental contribution to American historical scholarship. The writers were highly educated men, acute observers, conscientious recorders of what they saw and did. Leaving the most civilized country in Europe, these Frenchmen plunged into the unknown American wilderness and came face to face with the American Indian, whom they often found to be of the utmost ferocity. To achieve the spiritual conquest of the Indian, in all his various nations, tribes, and dialects, the missionaries had first to attain thorough knowledge of his languages, customs, and ceremonies, to penetrate into his strange cults, and to secure insight into his habits of thought and action. The missionaries were the first students of the American Indian, and they had the best possible opportunity for pursuing their study, since they lived in his wigwams and traveled with him on long journeys through the wilderness and upon the myriad lakes and rivers. The missionaries had attended the best colleges and universities in France. They were versed in the sacred sciences and in many branches of secular knowledge. They were able to make astronomical and meteorological observations, to chart maps, and to note what was peculiar in forestry, vegetation, and animal life. They were shrewd observers of racial characteristics. Many of the missionaries’ letters were written in Indian huts and wigwams and at campfires, amid a chaos of distractions: dogs barking, mosquitoes swarming over face and hands, smoke covering the missionaries like a pall, and dogs and children crawling over them alternately. Frequently the writers were suffering from fatigue and hunger, from sickness, from wounds inflicted by rude hosts who, at the twinkling of an eye, could change into jailers and tormentors upon the whisper of a medicine man or sorcerer. The style of the letters is nearly always simple and direct, informal and factual. The narrators indulge in no self-glorification nor self-pity; they do not dwell needlessly upon the details of their own hardships but rather set forth the facts with candor and objectivity. Considering the difficulties, it is a wonder that anything at all was written and dispatched. Jogues wrote some of his letters with a hand on which there remained but one whole finger; blood from a wound stained the paper. Gunpowder was his ink; the earth, his table. Here we have but a brief and inadequate account of the labors, toils, hardships and sacrifices made by some of the men of God! BORN TO DIE — DIED TO LIVE

Among the men of the seventeenth century, whose life-work has had a lasting influence, and whose fame, exalted as it has been up to this, has now become sacred and imperishable, are the eight missionaries who are known as the Jesuit Martyrs of North America.

The singular distinction of being the first in this part of the New World to be so honored belongs to Isaac Jogues, John de Brébeuf, Noel Chabanel, Anthony Daniel, Charles Garnier, Gabriel Lalemant, priests, and their companions, René Goupil and John Lalande, laymen. They were all born in France. They left that country when equipped for their life’s work to dwell and labor in the vast and unattractive wilderness known as Canada or New France, three of them, Jogues, Goupil and Lalande, penetrating into territory now part of the State of New York and dying there for the Faith. The sole object of these intrepid missionaries was the conversion of the savages who occupied these countries, principally the Hurons, Petuns, Neuters, Algonquins and Iroquois. Never did mortal men work so persistently, nor with such optimism amid every form of privation, obstacle, hardship, danger and reason for discouragement. Only for testimony which inspires conviction, what they endured would be incredible. Like giants they stand out even among their own heroic associates. Their savage tormenters ate the hearts and drank the blood of Lalemant and Brébeuf, hoping to partake of their courage and endurance. With the exception of John de Brébeuf who was born March 25, 1593, these martyrs were born and died in the first half of the seventeenth century. He was the only one to exceed fifty years of age, dying in 1649. In that brief space they accomplished the work of long years. The preparation for their arduous careers was the same for all. We know very little of the earliest years of some of them, prior to their entrance into the Society of Jesus. After that their manner of life is known minutely, in their various habitations and occupations, up to the time when those who were to become priests received Holy Orders. The first-born of the group, Brébeuf, appears on the scene only at his entrance into the Jesuit novitiate at Rouen, in 1617, already twenty-four years of age. Little is known of his life prior to that moment. Next to Brébeuf in order of years was Anthony Daniel, also Norman, from the seaport of Dieppe, born May 27, 1601. He had finished his rhetoric and philosophy, and was studying law when he decided to become a Jesuit, following Brébeuf in the Rouen novitiate in 1621. Four years younger than Daniel, Charles Garnier was a Parisian, born on May 25, 1605. He was educated at Clermont, then one of the most notable colleges in France. His parents were rich, but the money they allowed him went for the relief of prison inmates. At nineteen he became a Jesuit, following the usual training courses still at Clermont. Jogues, the first of these priests to die a martyr, was born in Orleans, January 10, 1607. Finishing his college course at seventeen, in 1624 he became a Jesuit novice at Rouen. Paris was the birthplace of Gabriel Lalemant, the last of the Martyrs to reach New France. He was born October 10, 1610. After making his vows as a Jesuit, in Paris, in 1632, he added a fourth vow to devote his life to the Indians. Youngest of all these missionaries was Chabanel, born February 2, 1613, in southern France near Mende, soon after the Huguenots had devastated that region. A Jesuit at the age of seventeen, he followed the usual courses of philosophy and theology, teaching between them for an interval of five years. Goupil and Lalande, lay assistants of the missionaries, both died as companions of Jogues. They were called by the name donnés, literally meaning, given, or dedicated to their work, oblates as we would style them now, a factor in the success of the priests which we can scarcely appreciate. Goupil was born at Angers, the same year as Jogues. Lalande’s birthplace was Dieppe: only that is known of him, and where and how he died so nobly. Goupil tried hard to be a Jesuit and he actually entered the novitiate, but his health forced him to resign. He then studied surgery and found his way to Canada, where he offered his services to the missionaries, matching the most heroic of them by his fidelity, fortitude in suffering and martyrdom. |

THE EIGHT NORTH AMERICAN MARTYRS (Part 2)

|

THE SOCIETY OF JESUS

The Society of Jesus, of which the six martyr priests were members, was then nearing the completion of the first century of its existence. Founded in 1540 by St. Ignatius Loyola, who had planned to restrict its membership to sixty, in 1615 it numbered 13,112 and was distributed over thirty-two provinces, with over five hundred and fifty houses, and three hundred and seventy-two of these attached to as many colleges.

The chief factor in the training of a Jesuit is called the Spiritual Exercises, the system, or method, as it may be called, of religious formation devised by Ignatius. The name means activity of the soul or spirit, just as manual or physical exercise means activity of the body. This spiritual activity moreover has a very definite purpose. Just as well-regulated bodily exercise fits muscle and nerve, joint and limb to perform various tasks with ease and pleasure, so these spiritual exercises gradually enable the faculties, mental and moral, to accomplish difficult things without failure or fatigue, even with delight. For most people it is irksome and even distasteful to meditate, especially when the object of the meditation is unusual or above their comprehension. They are content with saying mere words, without weighing their meaning. God, life, soul, duty, death, are known to them, but not so as to inspire them. Christ is an object of veneration, but more as if He were of the past rather than an animating principle for the present. The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius would change all this. The Spiritual Exercises are only a means to an end, and the end is to follow Christ as leader closely, to know Him intimately and to love Him with an affection for which He set the measure—the love greater than which no man can have, even to the laying down of life for a friend—the friend being Christ Himself. Charles Lalemant, the novice-master of Jogues, Brébeuf and Daniel, whose writings are today used by those who value real mysticism, must have been delighted with the response of these generous souls as he made known to them the invitation of Christ to help Him establish His Kingdom on earth, and set before them the two standards, that of Christ and that of Satan, not to bid them choose, but to make them more ardently devoted to their Leader, Christ. An appeal to the emotions! Yes, but to emotions stirred by a calm and enlightened reasoning, emotions which no mind can resist that dares reason rightly about Christ. It was this that prepared them for their life’s work. Some of them, Gabriel Lalemant, for instance, had become Jesuits with the purpose of becoming missionaries. Here was an appeal to all. The appeal was not to the enchantment of distant lands, nor to the romance of adventure, but to the task of preparation, the slow, dull, relentless effort to qualify for fields which needed the spirit of martyrs. The Spiritual Exercises animated Jogues and his companions with this martyr spirit, the spirit of an Order which, since its foundation has been—like Christ, after Whom it is named—a sign for contradiction. Only men of hardy fiber would venture overseas in those days to lands, where life was far more difficult and beset with peril than some of the most remote parts of the world today. Prior to the year 1608, none but fishermen and fur-dealers, Breton, Norman and Basque, would go there more or less regularly for their profitable wares, and they only to the coast line, always during milder seasons, and never to remain. A stronger and more disinterested motive was needed to allure men to penetrate a wilderness inhabited by uncivilized peoples, and dwell there during the fierce winters with no thought of returning to the country which was then at the summit of civilization. THE BRUTAL LIFE AMONG THE INDIANS

Brébeuf was one of this first group, with Massé and Charles Lalemant. They did not go at once to the Hurons, as they could not trust them at the time. Instead, Brébeuf wintered with the Algonquins, learning their ways and their language. What manner of life this was, we have from one who was to lead it about ten years later and who describes it vividly in one of his famous “Relations”. Le Jeune will write in 1634:

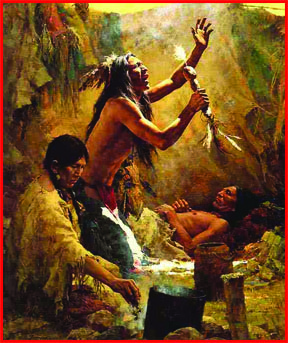

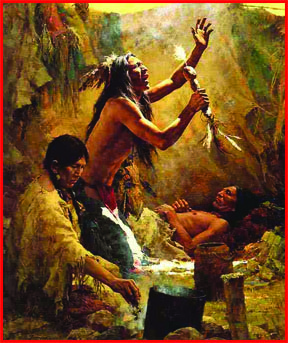

“Now, when we arrived at the place where we were to camp, the women, armed with axes, went here and there in the great forests, cutting the framework of the hostelry where we were to lodge; meantime the men, having drawn the plan thereof, cleared away the snow with their snowshoes, or with shovels which they make and carry expressly for this purpose. Imagine now a great ring or square in the snow, two, three or four feet deep, according to the weather or the place where they encamp. This depth of snow makes a white wall for us, which surrounds us on all sides, except the end where it is broken through to form the door. "The framework having been brought, which consists of twenty or thirty poles, more or less, according to the size of the cabin, it is planted, not upon the ground but upon the snow; then they throw upon these poles, which converge a little at the top, two or three rolls of bark sewed together, beginning at the bottom; and behold, the house is made. The ground inside, as well as the wall of snow which extends all around the cabin, is covered with little branches of fir; and as a finishing touch, a stretched skin is fastened to two poles to serve as a door, the doorposts being the snow itself. Now let us examine in detail all the comforts of this elegant mansion. “You cannot stand upright in this house, as much on account of its low roof as the suffocating smoke; and consequently you must always lie down, or sit flat upon the ground, the usual posture of the savages. When you go out, the cold, the snow, and the danger of getting lost in these great woods drive you in again more quickly than the wind, and keep you a prisoner in a dungeon, which has neither lock nor key. “This prison, in addition to the uncomfortable position that one must occupy on a bed of earth, has four other great discomforts, cold, heat, smoke, and dogs. As to the cold you have the snow at your head with only a pine branch between, often nothing but your hat, and the winds are free to enter in a thousand places. . . When I lay down at night I could study through this opening [in the roof] both the stars and the moon as easily as if I had been in the open fields. “Nevertheless, the cold did not annoy me as much as the heat from the fire. A little place like their cabins is easily heated by a good fire, which sometimes roasted and broiled me on all sides, for the cabin was so narrow that I could not protect myself against the heat. . . . “But, as to the smoke, I confess to you that it is martyrdom. It almost killed me, and made me weep continually, although I had neither grief nor sadness in my heart. It sometimes grounded all of us who were in the cabin; that is, it caused us to place our mouths against the earth in order to breathe. . . I sometimes thought I was going blind; my eyes burned like fire, they wept or distilled drops like an alembic; I no longer saw anything distinctly, like the good man who said, “I see men walking about like trees”, (Mark, 8:24). I repeated the psalms of my Breviary as best I could, knowing them half by heart, and waited until the pain might relax a little to recite the lessons; and when I came to read them they seemed written in letters of fire, or of scarlet. ... “As to the dogs, which I have mentioned as one of the discomforts of the savages’ houses, I do not know that I ought to blame them, for they have sometimes rendered me good service. True, they exacted from me the same courtesy they gave, so that we reciprocally aided each other, illustrating the idea of mutual benevolence. These poor beasts, not being able to live outdoors, came and lay down sometimes upon my shoulders, sometimes upon my feet, and as I only had one blanket to serve both as covering and mattress, I was not sorry for this protection, willingly restoring to them a part of the heat which I drew from them, It is true that, as they were large and numerous, they occasionally crowded and annoyed me so much, that in giving me a little heat they robbed me of my sleep, so that I very often drove them away. In doing this one night, there happened to me a little incident which caused some confusion and laughter; for, a savage having thrown himself upon me while asleep, I thought it was a dog, and finding a club at hand, I hit him, crying out, “Aché! Aché!” the words they use to drive away the dogs. My man woke up greatly astonished, thinking that all was lost; but having discovered whence came the blows, “You have no sense,” he said to me, “it is not a dog, it is I.” At these words I do not know who was the more astonished of us two; I gently dropped my club, very sorry at having found it so near me. “When I first went away with them, as they salt neither their soup nor their meat, and as filth itself presides over their cooking, I could not eat their mixtures, and contented myself with a few sea biscuits and smoked eel; until at last my host took me to task, because I ate so little, saying that I would starve myself before the famine overtook us. . . . It was not Our Lord’s will that they should be so long without capturing anything; but we usually had something to eat once in two days—indeed, we very often had a beaver in the morning, and in the evening of the next day a porcupine as big as a sucking pig. This was not much for nineteen of us, it is true, but this little sufficed to keep us alive. When I could have, toward the end of our supply of food, the skin of an eel for my day’s fare, I considered that I had breakfasted, dined, and supped well. “At first, I had used one of these skins to patch the cloth gown that I wore, as I forgot to bring some pieces with me; but, when I was so sorely pressed with hunger, I ate my pieces; and, if my gown had been made of the same stuff, I assure you I would have brought it back home much shorter than it was. Indeed, I ate old moose skins, which are much tougher than those of the eel; I went about through the woods biting the ends of the branches, and gnawing the more tender bark, as I shall relate in the journal. . . . “So these are the things that must be expected before undertaking to follow them; for, although they may not be pressed with famine every year, yet they run the risk every winter of not having food, or very little unless there are heavy snowfalls and a great many moose, which does not always happen. ... “It remains to me yet to speak of their conversation, in order to make it clearly understood what there is to suffer among these people. I had gone in company with my host and the renegade, on condition that we should not pass the winter with the sorcerer, whom I knew as a very wicked man. They had granted my conditions, but they were faithless, and kept not one of them, involving me in trouble with this pretended magician, as I shall relate hereafter. ... “. . . . Suffice it to say, that he sometimes attacked God to displease me; and that he tried to make me the laughingstock of small and great, abusing me in the other cabins as well as in ours. “He never had, however, the satisfaction of inciting our neighboring savages against me; they merely hung their heads when they heard the blessings he showered upon me. As to the servants, instigated by his example, and supported by his authority, they continually heaped upon me a thousand taunts and a thousand insults; and I was reduced to such a state, that, in order not to irritate them or give them any occasion to get angry, I passed whole days without opening my mouth. Believe me, if I have brought back no other fruits from the savages, I have at least learned many of the ‘insulting words of their language. . . "So these are some of the things that have to be endured among these people. This must not frighten anyone; good soldiers are animated with courage at the sight of their blood and their wounds, and God is greater than our hearts. One does not always encounter a famine; one does not always meet sorcerers or jugglers with so bad a temper as that one had; in a word, if we could understand the language, and reduce it to rules, there would be no more need of following these barbarians. As to the stationary tribes, from which we expect the greatest fruit, we can have our cabins apart, and consequently be freed from many of these great inconveniences.” THE HURON INDIANS

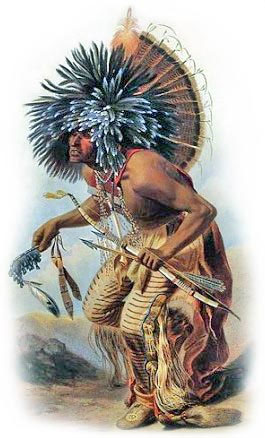

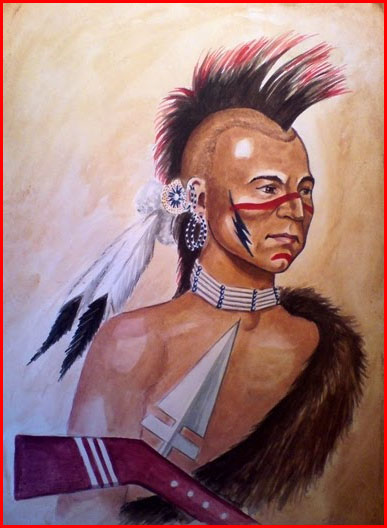

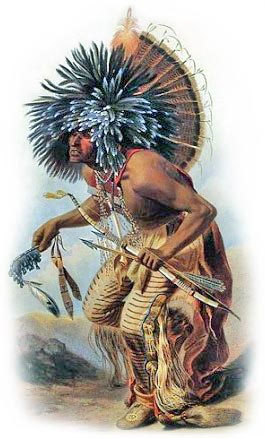

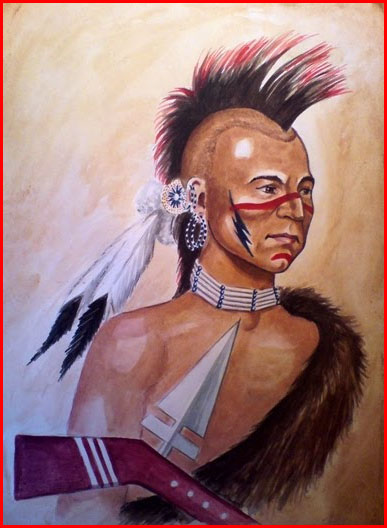

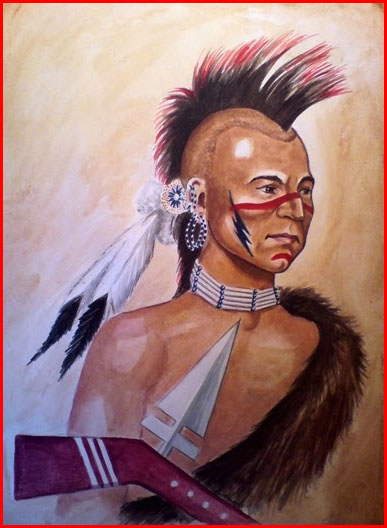

The Hurons were the original stock from which sprung the Iroquois family, Mohawks, Onondagas, Oneidas, Cayugas, Senecas and the Tuscaroras, Cherokees and Andastes. This has been established by all who have studied the derivation of the language of these tribes from that of the Hurons. Their real name was Wyandots, meaning “language [or land] apart”. Huron was a nickname given by French sailors who, on meeting some of them at Quebec with their hair furrowed and ridged like a boar’s bristles, exclaimed Quelle hure! (What boar heads!).

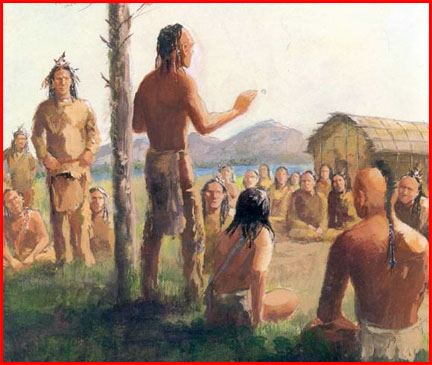

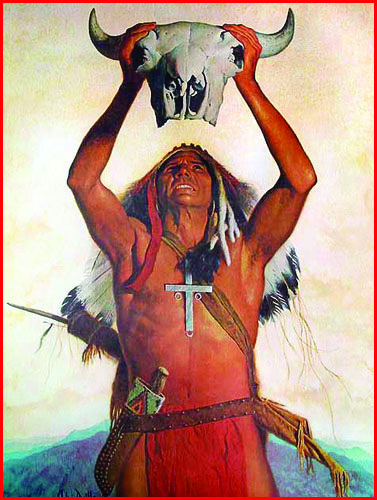

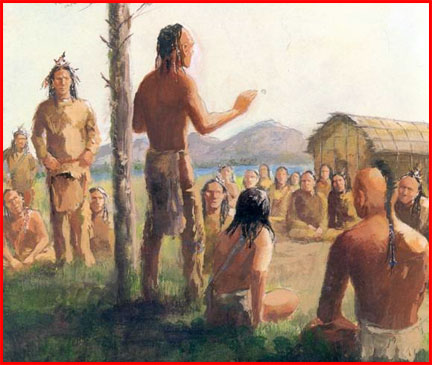

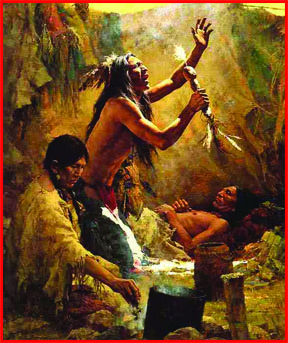

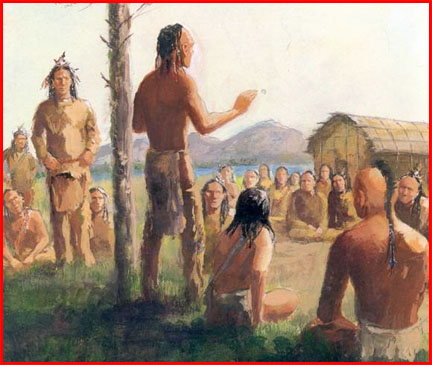

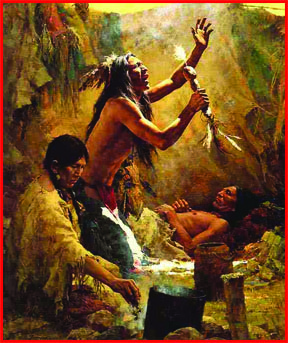

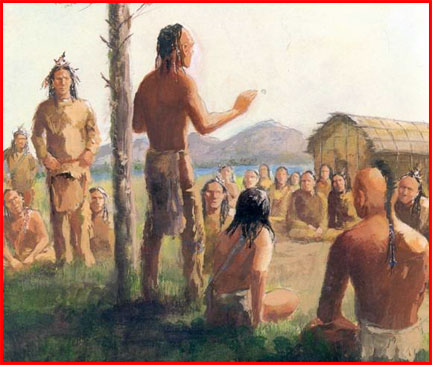

At the beginning of the seventeenth century the Hurons dwelt within the Province of Ontario, their main center being within Simcoe County. To the east and north were the Algonquins, to the south-west the Neutrals and Petuns, or Tobacco Nation. The number of Indians in Huronia in 1636 Brébeuf estimated at about thirty thousand, and the total number of all the tribes, Iroquois included, at more than three hundred thousand. It was not difficult to enumerate them, as they were not a wandering people. It was their settled habit of living that led the missionaries to have great hopes of civilizing and Christianizing them. War and pestilence were continually decreasing their number. Government, as we know it, was unknown among them. They lived in cabins divided into compartments on either side, like an enlarged sleeping car, a family to each compartment; and in the passage between the compartments a fire-place for every two families. They had councils for deliberation and political decisions, but there was no coercive power. It depended on the leaders, or captains, to persuade the tribesmen to submit to a decision, and on their power of invective to shame the guilty for his misdeeds. They had war chiefs to determine when there should be war and when peace. The affairs of each village, its games, festivals, ceremonies, funerals, were regulated by captains. These were chosen sometimes by election, sometimes by succession. They were all of equal grade: only mental or moral force, especially bravery, entitled any of them to impose his views on the others. Some of the missionaries, the Récollet Brother Sagard, for instance, and Jerome Lalemant, agreed with Champlain that the Hurons knew no God; that they worshipped a demon or Oki. Sagard was of the opinion that they had a good and bad Oki, and that they believed in a creator Iouskeha, though they did not offer him sacrifice. Brébeuf who lived closest to them concluded that they had a faint and hazy notion of God, but not impressive enough to make-them serve or honor Him. They believed that the soul survived the body, but soul for them was not a spiritual substance. They did not look forward to reward or punishment after death. They did, however, fear in this life the displeasure of the great Oki, the power which, in their view, regulated seasons, storms, tempests and other forces. They sought to propitiate this power by throwing tobacco into the flames and pleading for aid, for cures and for other needs. They appeased it by offering the flesh of the victims of violent death. They sacrificed living animals. This confirms Brébeuf’s view that they had a perverted notion of God, and that they were a degenerate people who were clinging to the remnant of a revelation their ancestors had once possessed. The Hurons were depraved and degraded. Vice ran riot among them. They were proud beyond conception, lustful, deceitful, thieving, cruel, brutal, filthy and repulsive. They were treacherous and hypocritical. Lavish in hospitality, they would feast to the full the victim they were to torture like demons as soon as the repast was over. The men wore scarcely anything; the women were covered from shoulder to knee. They held to the principle of marriage to one only, but they violated it in practice by the most promiscuous license. They were jealous of their traditions, and bound down by tribal customs and conventions. When inclined to follow a better instinct of decency, pity, honor, they were cowed into doing the opposite by fear of the tribal usage and sentiment. They taught their young to cultivate their vices. They believed in sorcery, and practiced it incessantly. Indeed they were constantly under the influence of those who pretended to be sorcerers. They were so given over to it; they believed that the missionaries must live by it also. This for many years was the chief obstacle to their conversion to Christianity. Indeed, it was the cause of the martyrdom of many a missionary at the hands of the Iroquois, who believed in it even, if possible, more than the Hurons. Brébeuf showed extraordinary physical courage in dwelling alone with these people. His moral courage was greater still. Not only did he fail to make any converts among them; he soon discovered that they were suspicious of everything about him. There was a drought, the crops were withering, and a contagious disease attacked them. They attributed their misfortunes to his presence and the most sacred things in his cabin. The cross on top of the chapel section of his cabin was the particular object of their dread. |

THE EIGHT NORTH AMERICAN MARTYRS (Part 3)

|

PLEA FOR HELP

There was so much work to be done that Brébeuf wrote a letter, to his superiors in Europe, asking for more help. Before Brébeuf’s letter reached France, recruits were already on the way, who would soon be with him in Huronia. His dream was to come true. The Jesuits in France had engaged to supply missionaries, and their engagement was like that of a nation pledging troops for war. The number eager to enlist, in this case, made it difficult for superiors to name who would be first to venture overseas. Early in 1636, they chose five among them, Jogues who was to be apostle to a new Indian nation, and martyr also, along with Garnier, another of the choice company. The others were Adam, Ragueneau and Chastellain, with a brother Cauvet.

Isaac Jogues wrote his farewells to his mother, of which the following is an extract: “I hope, as I said on another occasion, that if you take this little affliction in a proper spirit, it will be most pleasing to God, for whose sake it would become you to give, not one son only, but all the others, nay, life itself, if it were necessary. Men, for a little gain, cross the seas, enduring, at least, as much as we; and shall we not, for God’s love, do what men do for earthly interests! “Goodbye, dear mother. I thank you for all the affection which you have ever shown me, and above all at our last meeting. May God unite us in His holy paradise, if we do not see each other again on earth! “Your most humble son and obedient servant in Our Lord, Isaac Jogues. Dieppe, April 6, 1636.” He wrote to her after arriving at Quebec: “I do not know what it is to enter paradise; but this I know, that it is difficult to experience in this world a joy more excessive and more overflowing, than that I felt on my setting foot in New France, and celebrating my first Mass here, on the day of the Visitation. I assure you it was indeed a day of the visitation of the goodness of God and Our Lady. I felt as if it were a Christmas Day for me, and that I was to be born again to a new life, and a life in God.” Before leaving for the Huron mission he wrote still another letter on August 20th, as follows: “My health has been so good, thank God, at sea and on land that it has been a matter of wonder to all, it being very unusual for anyone to make such a long voyage, without suffering a little from sea-sickness, or nausea. The vestments and chapel service have been a great comfort to me, as I have offered the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass every day that the weather was favorable -- a happiness I should have been deprived of, had not our family provided me with them. It was a great consolation to me, and one which our Fathers did not enjoy the preceding years. Officers and crew have profited by it; as, but for that, the eighty persons on board could not have been present at the Holy Sacrifice for two months, whilst, owing to the faculties I enjoyed, they all confessed and received Communion at Whit Sunday, Ascension, and Corpus Christi. God will reward you and Madam Houdelin, for the good you have enabled me to do. “You shall have letters of mine every year, and I shall expect yours. It will ever be a consolation for me to hear from you and our family, as I have no hope of seeing you in our lifetime. May God in His goodness unite us both in His holy abode to praise Him for all eternity!” JOGUES SENT TO THE HURONS

It was not intended at first that Jogues should go immediately to the Hurons. For a time Brébeuf was there alone. He went through all the excitement of a threatened Iroquois invasion, and he had to witness the revolting scene of an Iroquois tortured unto death. He was powerless to prevent this, but, as he had baptized the captive shortly before his ordeal, he was determined to stand by, console and encourage him through such hellish treatment. It was then he witnessed an exhibition of Indian character which was new to him. Their mockery of the victim was fiendish. The more they burned his flesh and crushed his bones, the more they flattered and even coddled him. It was an all-night tragedy. Brébeuf was witnessing what he himself would afterwards suffer.

Le Mercier and Pijart had gone up, while Daniel and Davost were on their way down; Garnier and Chastellain went there directly, meeting Daniel on the way. Five would be enough for the time being. Providence had other designs. About August 20th, Daniel’s canoe came into Three Rivers with his young charges, and Jogues was there to witness his arrival. “Father Daniel was in this first company, Father Davost in the rear guard, which did not yet appear; and we even began to doubt whether the island savages had not made them return. At the sight of Father Daniel, our hearts melted; his face was joyful and happy, but greatly emaciated; he was barefooted, had a paddle in his hand, and was clad in a wretched cassock, his Breviary suspended to his neck, his shirt rotting on his back. He saluted our captains and our French people; then we embraced him, and, having led him to our little room, after having blessed and adored Our Lord, he related to us in what condition was the cause of Christianity among the Hurons, delivering to me the letters and the Relation sent from that country, which constrained us to sing a Te Deum, as a thanksgiving for the blessings that God was pouring out upon this new Church. I shall not speak of the difficulties of his voyage, all that has been already told; it was enough for him that he baptized a poor wretch they were leading to his death, to sweeten all his trials.” The Indians begged that a priest should accompany them homeward, and Jogues was selected for this errand. They left on St. Bartholomew’s Day, August 24th. At his first opportunity for getting a letter through, June 1st the following year, he wrote to his mother describing the journey with the same detail as Brébeuf, but more briefly, and with a story in addition about a sick Indian child, whom he had to look after, lifting him out of the canoe, carrying him over the portages. Now he is with his Indians and he can speak freely with a mother. He writes the following lines: “Nothing can equal the satisfaction enjoyed in our hearts, while we impart the knowledge of the True God to these heathen. About two hundred and forty have received baptism this year; among them I have baptized some who surely are now in Heaven, as they were children, one or two years old. “Can we think the life of man better employed than in this good work? What do I say? Would not all the labors of a thousand men be well rewarded in the conversion of a single soul gained to Jesus Christ? I have always felt a great love for this kind of life, and for a profession so excellent, and so akin to that of the Apostles. Had I to work for this happiness alone, I would exert myself to my utmost, to obtain a favor, for which I would fain give a thousand lives. “Should you receive these lines, I entreat you, by the bonds of the love of Jesus Christ, to give thanks to the Lord for this extraordinary favor He has bestowed upon me—a favor so earnestly wished and craved by many servants of God, endowed with qualities far above what I possess.” ILL-RECEIVED

An epidemic was raging in the village and Jogues was its first victim, among the missionaries. Garnier, Adam, Ragueneau and Chastellain followed. For a while Jogues lay at death’s door. As a desperate remedy bleeding was resorted to, and Jogues acted successfully as his own surgeon. He made a rapid recovery. In October he was up and about again. The others came round more slowly. All, even the convalescing, did what they could to minister to the afflicted Indians. Even in that time medical attention to the body was a way of approach to the soul. The Indians took what relief was afforded them, but ungratefully blamed the Fathers for having brought on their illness. The village sorcerer Tonneraouanont had offered to cure the Fathers by his incantations. He resented their declining. When he saw them grow well without his aid, he was convinced that they were greater sorcerers than himself.

It was not difficult for him and others like him to spread the impression that, by evil arts, the priests had brought this affliction on the village. Fortunately, on this occasion, the missionaries could prove that the village was the source of the contagion, but they could not remove every lurking suspicion, as the sequel will show. The plague was so persistent; the chiefs convoked a council at Ossossané, to deliberate on measures for eradicating it. Brébeuf and Jogues were present. Brébeuf began with prayer, distributed tobacco for the calumets, and, backed with presents, his proposal that the Indians give up superstitious practices, implore God’s mercy and adopt the Faith. The immediate thing to do was to erect a chapel. They all seemed to agree. They held their banquet, but their resolution was by no means stable. At Ihonatiria the missionaries had to face a new outbreak of suspicion and prejudice. The hostility to the Jesuits, especially in the Lutheran countries of Europe, followed them into Huronia through the Dutch settlement at Rensselaerswyck, now Albany. The Protestant burghers did not mean to incite the Hurons to molest their missionaries. This they proved later by their persistent efforts to obtain the release of Jogues from his Mohawk captors, and their pride in aiding his escape. They meant to warn them against accepting what the Catholic missionaries preached, giving as a reason that these men had brought on a blight in every country that tolerated them. Some of the Indians, who disliked the opposition of the missionaries to their superstitions, interpreted this to mean that the Jesuits had been the cause of their misfortunes. Everything they had and everything they did became suspect, their crucifix, their Breviary, clock, magnetic needle, the Sign of the Cross, kneeling to pray, writing a letter. Sorcerers themselves, the Indians adjudged everyone else the same. The situation became so trying that Jerome Lalemant wrote in the “Relation” for 1639: “I begin to doubt whether any other martyrdom is requisite for the end for which we labor; and I have not the least doubt that many would be found who would rather feel, at once, the keen edge of a hatchet on their head, than endure for years a life such as we have to live here every day.” Dreams go by contraries. With all this agitation against them the missionaries maintained their usual calmness. Jogues’ mind apparently was not disturbed by it. Life at Ihonatiria became impossible for the missionaries. Their work was hampered. The people were decimated by the epidemic. They were urged to settle in Ossossané (near Point Varwood on Nottawasaga Bay), and also at Teanaustayé, inland (near Hillsdale, in Medonté township), known as St. Joseph II. A chapel was built for them at the former place, eighty feet in length, with real boards and doors, and it was soon the scene of the baptism of Tsiouendaentaha, the first adult in good health admitted to baptism in that mission, after three years’ labor of an average of five men! There was humor as well as fitness in the name given him, Peter, since he was to be the corner-stone of Christianity in that remote region. The ceremony was solemn. The Indians, who loved ceremonial, flocked to it. The enemies of the missionaries made it an occasion of renewed hostility. The Fathers were unmoved. Brébeuf had the sachems call an assembly, appeared before it, and convinced them, apparently at least, that they were wrong in attributing sorcery to the priests. With quiet restored for a time, the work of the mission prospered. Like all untutored minds, the Indian’s was one of fixed ideas. Once seized with a belief, right or wrong, it was useless to argue with him. Early in August another council was called, ostensibly to consider tribal affairs, but in reality to determine the fate of the Jesuits. Twenty-eight villages were represented. Brébeuf was present. The first day was given to indifferent matters; on the second the session was in the evening, lasting until midnight. It was plain to Brébeuf that he and his companions were doomed. He was on trial. They abused and accused him. He defended himself fearlessly. Their decision was deferred until the return of their tribesmen from Quebec. An attempt was made to burn the mission cabin; the young men of the tribe harassed the Fathers wherever they met them. On October 4th, they were summoned to meet the elders of the tribe and informed that they should die. Brébeuf went about among the captains to obtain a stay of proceedings, but to no purpose. It was at this juncture he wrote a statement as heroic as any contained in the Acts of the Martyrs. Everyone at the mission signed it. Those who were absent made known their assent. |

THE EIGHT NORTH AMERICAN MARTYRS (Part 4)

|

LETTER TO THE SUPERIOR

“My Reverend Father,

“We are, perhaps, upon the point of shedding our blood and of sacrificing our lives to the service of our good Master, Jesus Christ. It seems that His goodness consents to accept this sacrifice from me for the expiation of my great and innumerable sins, and to crown from this time on, the past services and the great and ardent desires of all our Fathers who are here. “What makes me think that this will not happen is, on the one hand, the excess of my past wickedness, which renders me utterly unworthy of so signal a favor; and, on the other, that I do not believe His goodness will permit His workmen to be put to death, since through His grace there are still some good souls who eagerly receive the seed of the Gospel, notwithstanding the evil speech and persecutions of all men against us. And yet I fear that Divine justice, seeing the obstinacy of the majority of these barbarians in their follies, may very justly permit them to come and take away the life of the body from those who with all their hearts desire and procure the life of their souls. “Be this as it may, I will tell you that all our Fathers await the outcome of this affair with great calmness and contentment of mind. And, for myself, I can say to your reverence with all sincerity that I have not yet had the least apprehension of death for such a cause. But we are all sorry for this-that these poor barbarians, through their own malice, are closing the door to the Gospel and to grace. Whatever conclusion they reach, and whatever treatment they give us, we will try, by the grace of Our Lord, to endure it patiently for His service. It is a singular favor that His goodness extends to us, to make us endure something for His sake. It is now that we consider ourselves truly to belong to His Society. May He be forever blessed for having appointed us to this country, among many others better than we, to aid Him in bearing His Cross. In all things, may His holy will be done! If He will that at this hour we should die, oh, fortunate hour for us! If He will to reserve us for other labors, may He be blessed! If you hear that God has crowned our insignificant labors, or rather our desires, bless Him; for it is for Him that we desire to live and to die, and it is He who gives us grace therefor. For the rest, if any survive, I have given orders as to all they are to do. I have deemed it advisable for our Fathers and our domestics to withdraw to the houses of those whom they regard as their best friends; I have charged them to carry to the house of Pierre, our first Christian, all that belongs to the sacristy—above all, to be especially careful to put our dictionary, and all that we have of the language, in a place of safety. As for myself, if God grant me the grace to go to heaven, I will pray Him for them, for the poor Hurons, and I will not forget your reverence. “And finally, we supplicate your reverence and all our Fathers not to forget us in your holy Sacrifices and prayers, to the end that, in life after death, He may grant us mercy. We are all, in life and in eternity, Your Reverence’s Very humble and very affectionate servants in Our Lord, Jean De Brébeuf ; François Joseph Le Mercier; Pierre Chastellain; Charles Garnier; Paul Ragueneau. In the Residence of la Conception at Ossossané, this 28th of October. “I have left Fathers Pierre Pijart and Isaac Jogues in the Residence of Saint Joseph, with the same sentiments.” READY FOR DEATH

After that Brébeuf does the redoubtable thing which meant in Indian custom that all was ready for the execution. He invited them to his farewell feast, his Atsataion, the banquet they themselves gave when they were near death. They filled the cabin. He harangued them not about himself but about life after death. They departed gloomy and irresolute. The missionaries were left in peace. Brébeuf was adopted by the tribe and made a captain. Occasional attacks were made on some of the missionaries, on du Peron, Le Mercier, Chaumont and Ragueneau, but they were the frenzy of individuals, not of the tribe nor of its leaders.

Later when the contagion was at an end, in 1639 Jogues wrote to his brother: “During the epidemic the Fathers baptized more than one thousand two hundred persons. Even in the village where they were the most exposed to the perversity of the people, there were always some anxious to follow the instructions of our Fathers; about one hundred have been regenerated in the waters of baptism, amongst them twenty-two little children.” The new arrivals were busy with the language. In Brébeuf they had an excellent master and they all made quick progress. They made regular visits to the cabins, following as best they could the daily order detailed in a letter of François du Peron three years later: “The importunity of the savages—who are continually about us in our cabin, and who sometimes break down a door, throw stones at our cabin, and wound our people—this importunity, I say, does not prevent our observance of our hours, as well regulated as in one of our colleges in France. At four o’clock the rising-bell rings; then follows the morning meditation, at the end of which the Masses begin and continue until eight o’clock; during this period each one keeps silent, reads his spiritual book, and says his lesser hours. “At eight o’clock, the door is left open to the savages, until four in the evening; it is permitted to talk with the savages at this time, as much to instruct them as to learn their language. In this time, also, our Fathers visit the cabins of the town, to baptize the sick and to instruct the well; as for me, my employment is the study of the language, watching the cabin, helping the Christians and catechumens pray to God, and keeping school for their children from noon until two o’clock, when the bell rings for examination of conscience. “Then follows the dinner, during which is read some chapter from the Bible; and at supper Reverend Father du Barry’s Philagie of Jesus is read; the Benedicite and grace is said in Huron, on account of the savages who are present. We dine around the fire, seated on a log, with our plates on the ground. “At noon I open the school for the children who happen to be there up to two o’clock; sometimes I only have one, two, or three pupils. On Sundays, Tuesdays, and Thursdays, school closes at one o’clock, when instruction is given to the most prominent people of the village, whether Christians or not; on Thursdays, to Christians and catechumens only; on Sunday morning, to Christians only. “During the parochial Mass, the sermon is preached; before the Mass, the water is blessed while they are singing; and at, the offertory the bread, which the savages present in turn, is blessed. On great holy days, High Mass is celebrated. “After dinner on Sundays, at one o’clock, vespers are sung; then follows the instruction of Christians and catechumens; at five o’clock Compline is sung, and on Saturday evening the Salve, with the litanies of the Virgin. On this same day, at the close of school, a short catechetical instruction is given to the children; and once a month a public catechism is given to the whole village besides the daily instruction given them in their cabins. “At four o’clock in the evening, the savages who are not Christians are sent away, and we quietly say, all together, our matins and lauds, at the end of which we hold mutual consultation for three-quarters of an hour about the advancement of and the hindrances to the Faith in these countries; afterwards we confer together about the language until supper, which is at half-past-six; at eight o’clock, the litanies, examination of conscience, and then we retire to sleep.” This is what a visit to the cabins meant: “If you go to visit them in their cabins—and you must go there oftener than once a day, if you would perform your duty as you ought—you will find there a miniature picture of hell—seeing nothing, ordinarily, but fire and smoke, and on every side naked bodies, black and half roasted, mingled pell-mell with the dogs, which are held as dear as the children of the house, and share the beds, plates, and food of their masters. Everything is in a cloud of dust, and, if you go within, you will not reach the end of the cabin before you are completely befouled with soot, filth, and dirt.” ERA OF MARTYRDOM

Huronia was in distress. The mission itself was in great need. Harvests had been poor. Illness abounded. Clothing was scarce. The new mission stations needed vestments and altar-ware. Quebec was the only source of supplies. Raymbault’s illness required him to go there, but someone must accompany him. The Iroquois were on the warpath.

They were willing to make peace with the French, but not with the Hurons or Algonquins. The route lay through the villages of both. Jogues was chosen to lead the expedition. He started early in June, 1642, arriving safely about mid-July. It took about two weeks for his Indian companions to transact business and see what was of interest. Many of them were Christians, or preparing to be. They would naturally wish to see the Indian Catholic settlement at Sillery, the convents, hospitals, and churches. The Fathers encouraged this, as it was an object lesson which impressed on them the strength and dignity of religion. On August 1st he started homeward with about forty in the company, four of them Frenchmen, the canoes heavily laden with goods for the Mission. They were scarcely a day on the way when they were ambushed and taken captive by the Iroquois. The story of their ill-treatment, torture, captivity, and, in some instances, death has been frequently told, but never more impressively than by the principal victim, Jogues. Comment or paraphrase would spoil it. It is more like the “Confessions” of St. Augustine than a description of torture. Usually those who attempt to repeat the story in their own words apologize fastidiously for depicting such revolting cruelty. The language of Jogues lifts the imagination above gross details and center the attention more on his own spiritual elevation than on his bodily suffering. His letter was written to his provincial, or chief superior, in France. It is dated from the Mohawk village then located near the site of the present village of Auriesville, New York. To appreciate its contents one need only recall that the Iroquois were the fiercest Indian tribes in the cast at that time, that they were bitterly opposed to the French, implacable to the Hurons, hateful of the Black Robe, as the missionary was called on account of his clerical garment. There were five tribes or nations, Mohawks, Onondagas, Oneidas, Cayugas and Senecas, situated in this order along the Mohawk Valley, between Schenectady and Lake Erie. They numbered about twenty-five thousand and had twenty-five hundred warriors. The Auriesville village was the easternmost, and it was there Jogues was tortured and kept in captivity for fourteen months. It was near there he wrote what follows of this chapter, being at the time in the Dutch settlement Rensselaerswyck, now Albany. |

THE EIGHT NORTH AMERICAN MARTYRS (Part 5)

|

LETTER OF FR. ISAAC JOGUES TO HIS PROVINCIAL, FR. JOHN FILLEAU

August 5th, 1643 A Letter from the Past, that may Help Us in the Future! PART ONE OF TWO “When desiring to write to Your Reverence, the first doubt that I had was, in which language I ought to do so—Latin or French; then, having almost forgotten them both, I found equal difficulty in each.

Two reasons have moved me to use Latin. The first, for the sake of being able sometimes to employ certain sentences from the Sacred Scripture, from which I have received great consolation in my adversities. The second, because I desire that this letter may not be too common. Your Reverence’s great charity will excuse, as it has done at other times, my failings; especially since for eight years now I have been living among barbarians, not only in usages, but also in a costume similar to theirs. But I fear ‘that I am unskilled in speech and in knowledge’; not knowing the precious time ‘of my visitation’: first, then, I beg you, if this letter shall come unto your hands, to aid me with your Holy Sacrifices and prayers by the whole Province—as being among people no less barbarous by birth than in manners. And I hope you will do this gladly, when you shall have seen by this letter the obligation under which I am to God, and my need of spiritual help. We started from the Hurons on the 13th of June, 1642, with four canoes and twenty-three persons—eighteen barbarians, and five Frenchmen. The journey—besides the difficulties, especially of portages—was dangerous by reason of the enemies, who, seizing every year the highways, take many prisoners; and I know not how Father Jean de Brébeuf escaped them last year. They, being incensed against the French, had shortly before declared that, if they should capture any one of them, they would, besides the other torments, burn him alive by a slow fire. The Superiors, aware of the dangers of this journey—necessary, however, for the glory of God—spoke to me of them, adding that they did not oblige me thereto. But I did not gainsay them, ‘nor have I gone back’. I embraced with good courage that obedience put before me for the glory of God; and if I had excused myself, some one else, of greater ability would have been substituted in my place, with more detriment to the mission. We made the journey not without fear, dangers, losses, and shipwrecks, and, thirty-five days after our departure, we arrived safe and sound at the residence of Three Rivers; due thanks being there rendered to God, we spent twenty-five days partly there, partly at Kebek, according to necessity. Having finished our business, and celebrated the feast of our holy Father Ignatius, we embarked again on the first of August for the Hurons. On the second day of our journey, some of our men discovered on the shore fresh tracks of people who had passed there—without knowing whether or not they were enemies. Eustache Ahatsistari, famous and experienced in war, believes them enemies. ‘But, however strong they may be deemed,’ he says, ‘they are not more than three canoes; and therefore we have nothing to fear.’ We then continue the journey. But, a mile beyond, we meet them to the number of seventy, in twelve canoes, concealed in the grass and woods. They suddenly surround us, and fire their arquebuses, but without wounding us. The Hurons, terrified, abandon the canoes, and many flee to the deepest part of the woods; we were left alone, we four Frenchmen, with a few others, Christians and catechumens, to the number of twelve or fourteen. Having commended themselves to God, they stand on the defensive; but, being quickly overwhelmed by numbers, and a Frenchman named René Goupil, who was fighting among the first, being captured with some Hurons, they ceased from the defense. I, who was barefoot, would not and could not flee—not willing, moreover, to forsake a Frenchman and the Hurons, who were partly captured without baptism, partly near being the prey of the enemies, who were seeking them in the woods. I therefore stayed alone at the place where the skirmish had occurred, and surrendered myself to the man who was guarding the prisoners, that I might be made their companion in their perils, as I had been on the journey. He was amazed at what I did, and approached not without fear, to place me with them. I forthwith rejoiced with the Frenchman over the grace which the Lord was showing us: I roused him to constancy, and heard him in confession. After the Hurons had been instructed in the Faith, I baptized them; and as the number increased, my occupation of instructing and baptizing them also increased. There was finally led in among the captives the valiant Eustache Ahatsistari, a Christian; who seeing me, said: ‘I praise God that He has granted me what I so much desired—to live and die with thee.’ I knew not what to answer, being oppressed with compassion, when Guillaume Cousture also came up, who had come with me from the Hurons. This man, seeing the impossibility of longer defending himself, had fled with the others into the forests; and, as he was a young man not only of courageous disposition, but strong in body, and fleet in running, he was already out of the grasp of the one who was pursuing him. But, having turned back, and seeing that I was not with him, ‘I will not forsake,’ he said to himself, ‘my dear Father alone in the hands of enemies;’ and immediately returning to the barbarians, he had of his own accord become a prisoner. Oh, that he had never taken such a resolution! It is no consolation in such cases to have companions of one’s misfortunes. But who can prevent the sentiment of charity? Such is the feeling toward us of those laymen who, without any worldly interest, serve God and aid us in our ministrations among the Hurons. This one had slain, in the fight, one of the most prominent among the enemies; he was therefore treated most cruelly. They stripped him naked, and, like mad dogs, tore off his nails with their teeth, bit his fingers, and pierced his right hand with a javelin; but he suffered it all with invincible patience—remembering the nails of the Savior, as he told me afterward. I embraced him with great affection, and exhorted him to offer to God those pains, for himself and for those who tormented him. But those executioners although admiring me at the beginning, soon afterward grew fierce, and, assailing me with their fists and with knotty sticks, left me half dead on the ground, and a little later, having carried me back to where I was, they also tore off my nails, and bit with their teeth my two forefingers, causing me incredible pain. They did the same to René Goupil—leaving unharmed the Hurons, who were now made slaves. Then, having brought us all together again, they made us cross the river, where they divided among themselves the spoil—that is, the riches of the poor Hurons, and what they carried, which was church utensils, books, etc., things very precious to us. Meanwhile, I baptized some who had not yet received that rite—and, among others, an old man of eighty years, who, having had orders to embark with the others, said: ‘How shall I, who am already decrepit, go into a distant and foreign country?’ Refusing, then, to do so, he was slain at the same place where he had been baptized—losing the life of the body where he had received that of the soul. Thence, with shouts proper to conquerors, they depart, to conduct us into their countries, to the number of twenty-two captives, besides three of our men already killed. We suffered many hardships on the journey, wherein we spent thirty-eight days amid hunger, excessive heat, threats, and blows—in addition to the cruel pains of our wounds, not healed, which had putrefied, so that worms dropped from them. They, besides, even went so far—a savage act—as in cold blood to tear out our hair and beards, wounding us with their nails, which are extremely sharp, in the most tender and sensitive parts of the body. I do not mention the inward pains caused at the sight of that funereal pomp of the oldest and most excellent Christians of the new Church of the Hurons, who often drew the tears from my eyes, in the fear lest these cruelties might impede the progress of the Faith still incipient there. On the eighth day of our journey, we met two hundred barbarians, who were going to attack the French at the fort which they were building at Richelieu; these, after their fashion, thinking to exercise themselves in cruelty, and thus to derive prosperous results from their wars, wished to travel with us. Thanks being then rendered to the sun, which they believe to preside in wars, and their muskets being fired as a token of rejoicing, they made us disembark, in order to receive us with heavy blows of sticks. I, who was the last, and therefore more exposed to these beatings, fell, midway in the journey which we were obliged to make to a hill, on which they had erected a stage; and I thought that I must die there, because I neither could, nor cared to, arise. What I suffered, is known to One for Whose love and cause it is a pleasant and glorious thing to suffer. Finally, moved by a cruel mercy—wishing to conduct me alive to their country—they ceased beating me, and conducted me, half dead, to the stage—all bleeding from the blows which they had given me, especially in the face. Having come down from it, they loaded me with a thousand insults, and with new blows on the neck and on the rest of the body. They burned one of my fingers, and crushed another with their teeth; and the others, already bruised and their sinews torn, they so twisted that even at present, although partly healed, they are crippled and deformed. A barbarian twice took me by the nose, to cut it off ; but this was never allowed him by that Lord Who willed that I should still live—for the savages are not wont to give life to persons enormously mutilated. We spent there much of the night, and the rest of it passed not without great pain, and without food, which even for many days we had hardly tasted. Our pains were increased by the cruelties which they practised upon our Christians—especially upon Eustache, both of whose thumbs they cut off; and, through the midst of the wound made on his left hand they thrust a sharp skewer, even to the elbow, with unspeakable pain; but he suffered it with the same—that is, invincible—constancy. The day following, we encountered other canoes, which were likewise going to war; those people then cut off some fingers from our companions; not without our own fear. On the tenth day, in the afternoon, we left the canoes, in order to make the remainder of the four days’ journey on foot. To the customary severities was added a new toil, to carry their goods, although herein they treated me better than I expected, whether because I could not, or whether because I retained in captivity itself, and near to death, a spirit haply too proud. Hunger accompanied us always; we passed three days without any food, but on the fourth we found some wild fruits. I had not provided myself sufficiently when we abandoned the canoes, for fear lest my body should be too robust and vigorous in the fire and in the torments, not to dissimulate ‘about my infirmities’. On the second day, they put a kettle on the fire, as if to prepare something to eat; but there was nothing in it but warm water, which each one was allowed to drink at his pleasure. Finally, on the 18th day, the eve of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin, we arrived at the first village of the Hiroquois. I thanked the Lord that, on the day on which the Christians celebrate so solemn a feast, He had called us to share His pains. We had anticipated that day as truly bitter and calamitous; and it had been easy for René Goupil and for me to avoid it, because often, when unbound about midnight, we were able to flee—with the hope, if not of returning to ours, at least of dying more easily in the woods. But he refused to do so, and I would rather suffer every pain than abandon my French and Huron Christians to death, and deprive them of the consolation which they could receive from a priest at that time. So, on the eve of the Assumption, about the twentieth hour, we arrived at the river which flows past their village. Here were awaiting us, on both banks of the river, the old Huron slaves and the Hiroquois, the former to warn us that we should flee, for that otherwise we would be burned; the latter to beat us with sticks, fists, and stones, as before—especially my head, because they hate shaven and short hair. Two finger nails had been left me; they tore these out with their teeth, and tore off that flesh which is under them, with their very sharp nails, even to the bone. We remained there, exposed to their taunts a few moments; then they led us to the village situated on another hill. |

THE EIGHT NORTH AMERICAN MARTYRS (Part 6)

|

LETTER OF FR. ISAAC JOGUES TO HIS PROVINCIAL, FR. JOHN FILLEAU

August 5th, 1643 A Letter from the Past, that may Help Us in the Future! PART TWO OF TWO “Before arriving, we met the young men of the country, in a line, armed with sticks, as before, but we, who knew that, if we had separated ourselves from the number of those who are scourged, we would be separated from the number of the sons, ‘for He scourgeth every son whom He receiveth’, offered ourselves with ready will to our God, Who became paternally cruel to the end that He might take pleasure in us, as in His sons.