| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

The Greatest and Most Important Week in the Church's Liturgical Year

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

CLICK ON ANY HOLY WEEK LINK BELOW

Also lots of LENTEN & HOLY WEEK DOWNLOADS on the downloads page (click here)

LITURGICAL PRAYERS FOR EACH DAY OF THE WEEK DURING LENT

| Sundays of Lent | Mondays of Lent | Tuesdays of Lent | Wednesdays of Lent | Thursdays of Lent | Fridays of Lent | Saturdays of Lent |

HOLY WEEK PAGES

| Daily Thoughts | Holy Week Main Page | Before Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday | Last Days of Christ |

| Holy Thursday Last Supper Novena | Good Friday Passion Novena |

| Monday of Holy Week | Tuesday of Holy Week | Wednesday of Holy Week | Holy Thursday (Last Supper) | Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest) |

| Night Vigil With Christ | Good Friday (Pilate & Herod) | Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion) | Holy Saturday |

THE CHIEF CHARACTERS OF THE PASSION

| Characters of the Passion Mainpage | The Sanhedrin | Pharisees | Scribes | Saducees | Jewish Crowd | Roman Rulers |

| Judas | Annas & Caiphas | Pontius Pilate | Herod | Barabbas | Dismas the Good Thief | St. Peter | St. John | Mary Magdalen |

THE FOURTEEN STATIONS OF THE CROSS

| Introduction to the Stations of the Cross | Short Version of the Stations of the Cross (all 14 on one page) | 1st Station | 2nd Station | 3rd Station |

| 4th Station | 5th Station | 6th Station | 7th Station | 8th Station | 9th Station | 10th Station | 11th Station | 12th Station | 13th Station | 14th Station |

THE LAST SEVEN WORDS OF JESUS FROM THE CROSS

| Seven Last Words on the Cross (Introduction) | The 1st Word on the Cross | The 2nd Word on the Cross | The 3rd Word on the Cross |

| The 4th Word on the Cross | The 5th Word on the Cross | The 6th Word on the Cross | The 7th Word on the Cross |

PRAYERS AND DEVOTIONS TO THE SEVEN SORROWS OF OUR LADY

| Seven Sorrows Meditations | Short Prayers & Short Seven Sorrows Rosary | Longer Seven Sorrows Rosary |

| 1st Sorrow of Our Lady | 2nd Sorrow of Our Lady | 3rd Sorrow of Our Lady | 4th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| 5th Sorrow of Our Lady | 6th Sorrow of Our Lady | 7th Sorrow of Our Lady |

| Novena #1 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary | Novena #2 to the Sorrowful Heart of Mary |

LENTEN PAGES

| ASH WEDNESDAY COUNTDOWN | LENT (MAIN PAGE) | DAILY THOUGHTS | DAILY LENTEN LITURGY | DAILY LENTEN PLANNER |

| LENTEN PRAYERS | THE 7 PENITENTIAL PSALMS | IDEAS FOR PENANCE | LENT WITH AQUINAS | LENT WITH DOM GUERANGER |

| HISTORY OF PENANCE | PENANCES OF THE SAINTS | HOW EXPENSIVE IS SIN? | CONFESSION OF SINS | ARE FEW SOULS SAVED? |

| VIRTUES FOR LENT | FROM COLD TO HOT | LENTEN LAUGHS | SERMONS FOR LENT | LETTER TO FRIENDS OF THE CROSS |

| STATIONS OF THE CROSS (INDIVIDUALLY) | ALL 14 STATIONS OF THE CROSS |

| THE LAST DAYS OF CHRIST | SPECIAL HOLY WEEK PAGES |

ANNAS & CAIPHAS

|

First―A Word About the Priesthood

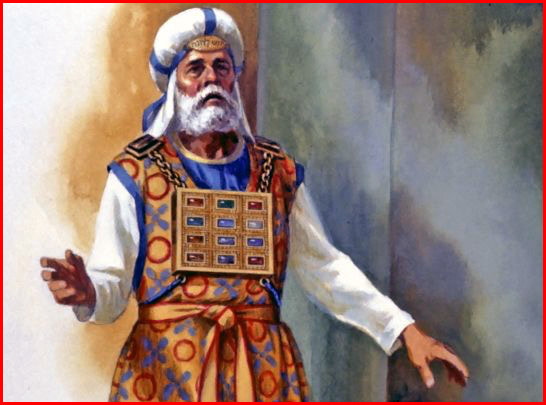

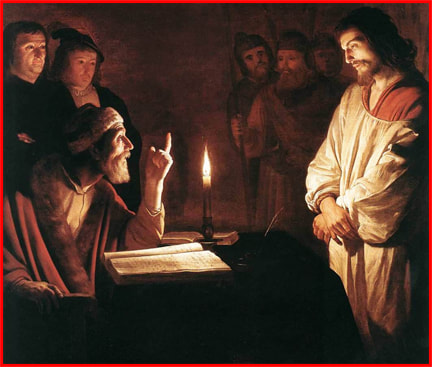

The Levitical priesthood, with the high priest at its head, presided over the Temple. Because of the theocratic organization of Judaism (meaning God was king, as opposed to a monarchy where one man in king), the high priest was also head of the whole Jewish nation in God’s Name (much like the Pope is, in God’s Name, the vicar or head of the Catholic Church today). In the high priest were joined the supreme religious and civil authority. This was true in theory, but in practice, especially at the time of Jesus, the actual power of the high priest was not that great. At that time the high priests were almost always chosen from among certain particularly influential sacerdotal families which formed a privileged and aristocratic group within the sacerdotal class. The high priest was chosen for life and, in ancient times, it had been the exception when he was deposed, but from the time of Herod the Great, the exception became the rule, and a high priest rarely died in office. From the beginning of the reign of Herod the Great to the death of Jesus, about sixty-five years, there were approximately fifteen high priests, several of whom held office only a year or less. The former high priests, with the other members of their privileged families, formed the group to which the Gospels and Flavius Josephus refer as “the chief priests.” Once elected, the high priest was the chief minister of public worship and head of all the services in the Temple. He had to celebrate personally only the ceremony of the Day of Atonement, but he sometimes officiated on other solemn feast days also, such as the Pasch. With regard to civil matters the high priest functioned principally as head of the Sanhedrin, the presidency of which was automatically his. But here especially his actual power dwindled under Herod the Great, who pointed out with his sword the road the head of the Sanhedrin was to follow. The Roman procurators were less brutal about it, but they watched his actions and reviewed his most important decisions to remind him, among other things, that the miter of the priest was no royal crown. In fact, even the high priest's vestments were kept by the Romans in the Antonia (the Roman fortress in Jerusalem), to be taken out only on the principal feast days and immediately returned to the fortress. But in 36 AD, after Pontius Pilate was deposed, the Romans renounced this practice, which was hateful to the religious sensibilities of the Jews. The fact that the high priests were always Sadducees (read more here) was another reason why the moral prestige, if not actually the official authority, of the high priests was at a very low ebb at the time of Jesus. Not only was this aristocratic faction cordially disliked by the common people, but its doctrinal tendencies were opposed by the democratic Pharisees (read more here) and therefore by the Scribes (read more here), the majority of whom were also Pharisees. Now, the high priest should have sat on the chair of Moses as supreme moderator and interpreter of the theocratic Law, but in reality “the Scribes and the Pharisees have sitten on the chair of Moses” (Matthew 23:2) ; in other words, they set up another chair in opposition to that of the high priest, turning the multitude from him and leaving him only his self-interested Sadducees. The high priests who figure directly in the story of Jesus are two―Annas and Caiphas. ANNAS Annas was the first High Priest of the newly formed Roman province of Judea in 6 AD; just after the Romans had deposed Archelaus, Ethnarch of Judea, thereby putting Judea directly under Roman rule. Annas officially served as High Priest for ten years (6–15 AD), when, at the age of 36, he was deposed by the procurator Valerius Gratus. Yet, while having been officially removed from office, he remained as one of the nation’s most influential political and social individuals, aided greatly by the use of his sons and his son-in-law Caiphas as puppet High Priests. No less than seven members of his family held the office of High Priest―his five sons, namely, Eleazar, Jonathan, Theophilus, Matthias, and Annas the younger; his grandson, the son of Theophilus; and also his son-in-law, Caiphas. It is not surprising, therefore, that he wielded great influence. Some maintain that the two, Annas and Caiaphas, were together at the head of the Jewish people―Caiaphas as actual high priest, Annas as resident of the Sanhedrin (Acts 4:6). Other historians think that Annas held the office of sagin, or substitute of the High Priest; while some hold that Annas held the title of High Priest and was really the ruling power. His death is unrecorded, but his son, Annas the Younger, also known as “Ananus the son of Ananus” was assassinated in 66 AD for advocating peace with Rome. The Jewish historian of that day, Flavius Josephus, says Annas was a “most happy man” for two reasons: he himself had been High Priest for a very long time, and then he had been succeeded in office by five of his sons. Josephus might have mentioned that his son-in-law Joseph, called Caiphas, also succeeded him, which brings out even more clearly the monopoly of the High Priesthood exercised by the influential families mentioned before. Annas still had very great authority even after he was removed from office, for he secretly, or openly, controlled the pontificates of his five sons and his son-in-law. In the modern age, you could compare Annas to a Mafia “godfather”, who typically has absolute or nearly absolute control over his subordinates, is greatly feared by his subordinates for his ruthlessness and willingness to take lives to exert his influence. Even though Flavius Josephus says that the people considered him happy and fortunate; but his reputation did not match his supposed happiness, for he was known to be grasping and overbearing, vices which were common to other great priestly families such as those of Boethus, Phabi and Camithus, as well as that of Annas. Of these priests Josephus tells us that “they stirred up riots in the city, and that their avarice and arrogance reached such extremes that they sent their servants to the threshing floors to exact on their account the tithes which were due to the ordinary priests, leaving the latter to die of hunger.” And, it was commonly said, that they bought the dignity of the High Priesthood for gold and added to their wealth by evil means. We also know that the High Priest, Annas, son of the Annas mentioned in the Gospel, had St. James the Less stoned; therefore, some authors conclude, he had the power to pass sentence of death. But Josephus notes that Annas’ procedure was unlawful. CAIPHAS Joseph Caiphas was the son-in-law of Annas, who had been High Priest from 6 to 15 AD. Annas was at the head of a family that would control the High Priesthood for most of the first century. Annas is also mentioned in the Biblical accounts of the arrest and trial of Jesus. It is highly likely that he, as a former High Priest, might have served at the side of Caiphas in the Sanhedrin called to resolve the fate of Jesus. Annas’s son-in-law, Joseph, Caiphas had been appointed 18 AD, by Valerius Gratus, the Roman procurator for Judea, who had deposed his father-in-law, Annas, from his position as High Priest . After his appointment in 18 AD, Caiphas remained in office until 36 AD―thus reigning for around 19 years, almost twice as long as Annas had reigned. He was, therefore, the reigning High Priest when Jesus was condemned, although on that occasion Annas wielded the actual authority behind the scenes. As High Priest and chief religious authority in the land, Caiphas had many important responsibilities, including controlling the Temple treasury, managing the Temple police and other personnel, performing religious rituals, and--central to the passion story―serving as president of the Sanhedrin, the Jewish council and court, that examined the case of Jesus. The High Priest had another, more controversial function in first-century Jerusalem: serving as a sort of liaison between Roman authority and the Jewish population. High priests, drawn from the Sadducean aristocracy, received their appointment from Rome since the time of Herod the Great, and Rome looked to High Priests to keep the Jewish populace in line. We know from other cases (such as one incident in 66 AD) that Roman prefects might demand that High Priests arrest and turn over Jews seen as agitators. After the death of Jesus, Caiphas continued to persecute His followers. When Peter and John were brought before the Council, after the cure of the lame man at the Beautiful Gate of the Temple (Acts 4:6 sqq.), Caiphas was still High Priest, since he was only removed around 36 or 37 AD. We can say with almost equal certainty that he was the High Priest before whom St. Stephen appeared (Acts 7:1), and that it is from him that Saul obtained letters authorizing him to bring the Christians of Damascus to Jerusalem (Acts 9:1-2). We know little about Caiphas’ life, but from his conduct in our Lord’s trial we can gather that he was both violent and unscrupulous. And it would not be rash to suspect that he attained and kept his high office by shameless bribery, fawning flattery and base compromise. Although little is known of Caiphas, historians infer from his long term of office as High Priest, from 18 to 36 AD, that he must have worked well with Roman authority. For ten years, Caiphas served alongside the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate (who governed from 25-36 AD). The two presumably had a close relationship. It is likely that Caiphas and Pilate had standing arrangements for how to deal with subversive persons. Caiphas’s motives in turning Jesus over to Pilate are a subject of speculation. Some historians suggest that he had little choice. Others argue that Caiphas saw Jesus as a threat to the existing religious order. He might have believed that if Jesus wasn’t restrained, or even executed, that the Romans might end their relative tolerance of Jewish institutions. That might well be true—but you can surely add a possible personal dislike for Jesus, since Jesus was preaching against the very kind of lifestyle that Caiphas was leading. Unlike other Temple priests, Caiphas, as a High Priest, lived in Jerusalem’s Upper City, a wealthy section inhabited by the city’s powers-that-be. His home almost certainly was constructed around a large courtyard. High priests, including Caiphas, were both respected and despised by the Jewish population. As the highest religious authority, they were seen as playing a critical role in religious life and the Sanhedrin. At the same time, however, many Jews resented the close relationship that High Priest maintained with Roman authorities and suspected them of taking bribes, or practicing other forms of corruption. In the year 36 AD, both Caiphas and Pilate were dismissed from office by Syrian governor, Vitellius, according to Jewish historian Flavius Josephus. It seems likely that the cause of their dismissal was growing public unhappiness with their close cooperation and likely corruption. Rome might have perceived the need for a conciliatory gesture to Jews, whose sensibilities had been offended by the two leaders. Flavius Josephus described the High Priests of the family of Annas as “heartless when they sit in judgment.” |

Web Hosting by Just Host