| Devotion to Our Lady |

|

- Homepage

-

Daily Thoughts

- 2023 October Daily Thoughts

- Daily Thoughts Lent 2020

- Daily Thoughts for Advent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for October 2019

- Daily Thoughts for September 2019

- Daily Thoughts for August 2019

- Daily Thoughts for July

- Daily Thoughts for June

- Daily Thoughts for Easter 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Lent 2019

- Daily Thoughts for Christmas

- Daily Thoughts Easter 2022

- Sacred Heart

- Holy Ghost

-

Spiritual Life

- Holy Mass Explained

- First Friday Devotions

- First Saturday Devotions

- The Mercy of God

- Vocations

- The Path Everyone Must Walk >

- Gift of Failure

- Halloween or Hell-O-Ween?

- Ignatian Spiritual Exercises >

- Meditation is Soul-Saving

- Spiritual Communion

- Miraculous Medal

- Enrollment in Miraculous Medal

- St. Benedict Medal

- Holy Water

- Advice on Prayer

- Your Daily Mary

-

Prayers

- September Devotions

- Seven Sorrows of Our Lady

-

Novenas

>

- NV-Help of Christians

- NV-Nativity of Our Lady

- NV-Seven Sorrows

- NV- Sorrowful Heart

- NV-Pope St Pius X

- NV-La Salette

- NV-St Michael Archangel

- NV-Immaculate Heart

- NV-Assumption

- NV-Novena for Fathers

- NV-Novena for Your Mother

- NV-St Raphael Archangel

- NV-Souls in Purgatory

- NV-All Saints Day

- NV-Christ the King

- NV-Divine Motherhood

- NV-Guardian Angels

- NV-Rosary

- NV-Mirac Med

- NV- Imm Conc

- NV - Guadalupe

- NV - Nativity of Jesus

- NV-Epiphany

- NV-OL Good Success

- NV-Lourdes

- NV-St Patrick

- NV-St Joseph

- NV-Annunciation

- NV-St Louis de Montfort

- NV-OL Good Counsel

- NV-Last Supper

- NV-Passion

- NV-Pentecost

- NV-Ascension

- NV-Sacred Heart

- NV-Sacred Heart & Perpetual Help

- NV-Corpus Christi

- NV-OL of Perpetual Help

- NV-Queenship BVM

- NV-OL of Mount Carmel

- NV-St Mary Magdalen

- NV- Im Hrt

- August Devotions to IHM

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Litany of Dependence

- Prayers to St Mary Magdalen

- Prayers in Times of Sickness Disease & Danger

- Holy Souls in Purgatory

- Meditations on the Litany of Our Lady

- Special Feast Days

- Prayers to Mary (Mon-Sun)

- Litanies to Our Lady >

- Various & Special Needs

- Our Lady of the Rosary

- Our Lady of Mt. Carmel

- Our Lady of Perpetual Help

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Other titles of Our Lady

-

Rosary

- Downloads

- Consecration

- Easter Season

-

Holy Week

- Last Seven Words of Jesus >

- Characters of Passion >

- The Last Days of Christ

- Before Palm Sunday

- Palm Sunday

- Monday in Holy Week

- Tuesday in Holy Week

- Wednesday in Holy Week

- Holy Thursday (Last Supper)

- Holy Thursday (Agony & Arrest)

- Night Vigil with Christ

- Good Friday (Pilate & Herod)

- Good Friday (Way of Cross & Crucifixion)

- Saturday in Holy Week

-

Lent

- Ideas for Lent

- Daily Lenten Planner

- Daily Lenten Liturgy

- From Cold to Hot

- Lent with Aquinas

- Lent with Dom Gueranger

- Virtues for Lent

- History of Penance

- How Expensive is Sin?

- Confession of Sins

- Letter to Friends of the Cross

- Sermons for Lent

- Stations of the Cross >

- Lenten Prayers

- 7 Penitential Psalms

- Lenten Psalms SUN

- Lenten Psalms MON

- Lenten Psalms TUE

- Lenten Psalms WED

- Lenten Psalms THU

- Lenten Psalms FRI

- Lenten Psalms SAT

- Lenten Laughs

- Septuagesima

-

Christmas

- Epiphany Explained

- Suggestions for Christmas

- Food For Thought

- Christmas with Aquinas

- Christmas with Dom Gueranger

- Christmas Prayers

- Candles & Candlemas

- Christmas Sermons

- Christmas Prayers SUN

- Christmas Prayers MON

- Christmas Prayers TUE

- Christmas Prayers WED

- Christmas Prayers THU

- Christmas Prayers FRI

- Christmas Prayers SAT

- Twelve Days of Christmas >

-

Advent Journey

- Purgatory

- Christ the King

- Legion of Mary

- Scapular

-

Saints

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Your Daily Martyr >

- All 365 Days of Martyrs

- Cristeros

- St Valentine & Valentine's Day

- Martyrs--Thomas Becket

- Martyrs--John the Apostle

- Holy Machabees

- Age of Martyrdom

- Carmelites of Compiegne

- Martyrs--Peter & Paul

- Martyrs--John the Baptist

- Martyrs--Andrew

- Martyrs--James the Great

- Martyrs--North American

- Martyrs--Seven Holy Sleepers

- Martyrs--Afra

- School of Martyrdom

- Martyrs--Christina

- Desert Saints >

- Saints for Sinners >

- Saints of Mary >

- History of All Saints Day

-

Martyrs for the Faith

>

- Precious Blood

- Synod 2023

-

Catechism

- Catechism Lesson 1

- Catechism Lesson 2

- Catechism Lesson 3

- Catechism Lesson 4

- Catechism Lesson 5

- Catechism Lesson 6

- Catechism Lesson 7

- Catechism Lesson 8

- Catechism Lesson 9

- Catechism Lesson 10

- Catechism Lesson 11

- Catechism Lesson 12

- Catechism Lesson 13

- Catechism Lesson 14

- Catechism Lesson 15

- Catechism Lesson 16

- Catechism Lesson 17

- Catechism Lesson 18

- Catechism Lesson 19

- Catechism Lesson 20

- Catechism Lesson 21

- Catechism Lesson 22

- Bible Study

-

Calendar

- Miracles

- Apparitions

- Shrines

- Prophecies

- Angels Homepage

- Hell

-

Church Crisis

- Conspiracy Theories

- Amazon Synod 2019 >

- Liberalism & Modernism

- Modernism--Encyclical Pascendi

- Modernism & Children

- Modernism--Documents

- The Francis Pages

- Church Enemies on Francis

- Francis Quotes

- Amoris Laetitia Critique

- Danger of Ignorance (Pius X)

- Restore all In Christ (Pius X)

- Catholic Action (Pius X)

- Another TITANIC Disaster?

- The "Errors of Russia"

- CRISIS PRAYERS

- Election Novena 2024

- The Anger Room

- War Zone

- Life of Mary

- Spiritual Gym

- Stupidity

- Coronavirus and Catholicism

- History & Facts

- Books

- Catholic Family

- Children

- Daily Quiz

-

Novena Church & Pope

- Day 01 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 02 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 03 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 04 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 05 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 06 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 07 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 08 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 09 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 10 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 11 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 12 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 13 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 14 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 15 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 16 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 17 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 18 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 19 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 20 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 21 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 22 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 23 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 24 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 25 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 26 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 27 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 28 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 29 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 30 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 31 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 32 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 33 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 34 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 35 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 36 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 37 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 38 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 39 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 40 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 41 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 42 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 43 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 44 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 45 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 46 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 47 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 48 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 49 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 50 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 51 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 52 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 53 Church-Pope Novena

- Day 54 Church-Pope Novena

- Penance Novena

- Daily WeAtheR Forecast

TO VISIT A SHRINE

click on the shrine you would like to view

| Bethlehem | Nazareth | Lanciano | Lourdes | La Salette | Fatima | Guadalupe | Walsingham | Mount Carmel |

| Our Lady of Perpetual Help | St. Patrick's Purgatory |

click on the shrine you would like to view

| Bethlehem | Nazareth | Lanciano | Lourdes | La Salette | Fatima | Guadalupe | Walsingham | Mount Carmel |

| Our Lady of Perpetual Help | St. Patrick's Purgatory |

The Lough Derg Pilgrimage is a penitential retreat on an island in County Donegal, on the northwestern tip of Ireland. The pilgrimage is also referred to as "St Patrick's Purgatory." It is believed that St Patrick stayed in a cave there. Legend has it that St Patrick was subjected to many temptations and was also given a vision of Hell, hence the title "St Patrick's Purgatory. "

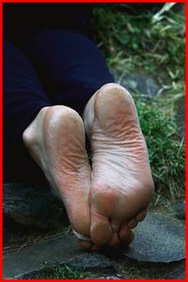

In recent decades, the pilgrimage has become popular with hundreds of thousands of people making the trip to Donegal. The pilgrimage is based on the theme of Purgatory. Pilgrims undertake a three-day fast for the period of the retreat. No food is taken except for black tea/coffee and dry toast. On arrival at the island, pilgrims remove their footwear and complete the pilgrimage bare-footed.

The Pilgrimage Exercises consist of a prayer sequence called a "Station." It is a familiar form of prayer in the Celtic tradition and involves moving around from Station to Station while saying certain prayers. Over the three-day period, a total of nine Stations are completed — five in the open air on the Pentitential Beds and four inside the Basilica. Each Station outside is dedicated to a saint — Brigid, Brendan, Catherine, Columba, Patrick, Davog and Molaiste.

Below, you can read more a detailed account of the history of the shrine and the procedure of the retreat.

|

THE BASIC FACTS

This page introduces you to Saint Patrick’s Purgatory on Lough Derg, County Donegal, where 20,000 pilgrims come every year between 1st June and 15th August to follow an organized three-day program of prayer and penance.

ST. PATRICK

BRIEF LIFE STORY Saint Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, is one of Christianity’s most widely known figures, which is also a clear indication of the Irish influence throughout the world.

Is St. Patrick Irish? No, it is presumed that his birthplace is somewhere in Scotland, the son of a Roman family who had migrated to England. he was born around 390 A.D., and his real name was Succat Maewyn, however, he was baptized as Patricius, meaning “noble”. His parents, Calpurnius and Concess, were high ranking Romans. Although, his family had significant involvement with the church, Maewyn was not particularly religious. In his mid-teens, his village was invaded by Irish raiders. leading the raid was the great High King Niall of the nine hostages, during the raid and plunder, Maewyn’s father was killed and many people were taken as slaves, including Maewyn himself and his two sisters, Lupida and Daererca. Upon the return of King Niall to Ireland with his hostages, Maewyn was sold to Milchu, who was either a king or a chief. It is not known what happened to his sisters. Maewyn who had known a life of luxury and comfort spent six years in Ireland under severe conditions as a slave, attending to the livestock of his new master. During this period he became fluent in the Irish language. During this time, Maewyn felt forgotten, lonely and desperate. He started to pray and found God. Later he wrote: “Thus was I purged by the Lord; and He made me fit so that I might be now what was once far from me, that I should care and labor for the salvation of others, whereas then I did not even care about myself.” Later, Maewyn told about a dream which he had in his mid-twenties. A voice was saying: “Lo, your ship is ready.” He knew, the voice came from God telling him to leave Ireland. Maewyn ran away from Milchu and went to the South Coast of Ireland to a town called Wexford, were he got a boat in which he escaped to Gaul in France. Maewyn pleaded to the captain to give him free passage, but the captain refused, Maewyn then prayed to God for guidance. As if a miracle, the crew called him to come on-board, as the captain had changed his mind. He further endured hardship in France and decided to return to Britain. Maewyn seemed destined not to have an easy life. During his travel in Britain, he was captured by a band of brigands, and again he was sold into slavery. The second time he heard a voice in his dream reassuring him that “Two month will you be with them.” He escaped after sixty days. Maewyn traveled throughout England and Europe for the next seven years, trying to determine what his purpose was. He came to the conclusion that he would study to become a priest. He studied at the Lerin Monastery, of the island of Cote d’Azur. At his ordination he took on the name of Patrick (Patrick Magonus Sucatus). Now a priest, he returned to Britain and remained there until he heard a voice again begging him, “We beseech thee, holy youth, to come and walk once more amongst us.” Patrick now seemed to know his purpose in life—to convert the Irish people to Christianity. Patrick decided to further his education which was limited due to his slavery. He decided to return to France, to the monastery of Auxerre, where he was already known for his dedication and enthusiasm. Later, the monks decided to send a missioner to Ireland. To his disappointment they chose Palladius and not him. But not long after, news reached the monastery that Palladius had died. The monks decided to send another mission to Ireland which Patrick would lead. Patrick was called to Rome in 432 A.D., where Pope Celestine bequeathed the honor of bishop upon him before he was to go on his holy mission to Ireland. Now a bishop, he arrived in Ireland in the winter of 432 A.D. with 25 followers. A local landowner, with the name of Dichiu, provided food and shelter for the band of religious crusaders. Dichiu was among the first who converted to Christianity. The following year, in springtime, Patrick decided to address Laoghaire, the High King of Tara, who ruled Ireland and was the most powerful man. Patrick knew, if he wanted to crusade through Ireland and spread Christianity, he would need the King’s support, he also knew, he needed to make a dramatic impression. King Laoghaire had a tradition to start spring with a huge bonfire (the Irish were used to honor their Gods with fire). King Laoghaire personally would light the first fire before everybody else could. Patrick and his supporters lit a massive bonfire on March 25, 433 A.D., before King Laoghaire. When King Laoghaire saw the distant high flames in the air, he gathered the princes with their war chariots around him and raced towards the fire to see who had challenged his authority. When King Laoghaire arrived at the fire, the contrast between those two groups was quite dramatic. King Laoghaire and his princes wore rich garments with jewelry in comparison to the plain cloth worn by Patrick and his followers. Patrick spoke in a calm, concise and very confident voice, stating that he had no intention of defying his authority, but only to spread the Gospel among the Irish people. King Laoghaire was impressed by Patrick’s composure and invited him to the Royal Court at Tara the next day. Patrick arrived with a massive cross, accompanied by his followers. They were singing hymns that are still known as the Breastplate of St. Patrick. Patrick approached King Laoghaire saying: “Here I am.” The king in response took Patrick’s hands and kissed him on the cheek. Legend says, that the druids, worried that the king would accept Patrick’s religion, asked Patrick if he could make it snow. Patrick sensing a trap replied, that it was only God who could determine the weather. Yet, at that moment, it began to snow in the middle of a sunny spring day. Patrick made the sign of a cross and, miraculously, the snow disappeared and sunshine resumed. It is said that King Laoghaire, wanted to know more about the religion which St. Patrick intended to spread throughout Ireland. Patrick stated that unlike the Gaels, Christians only worshiped one God. And when St. Patrick desperately tried to explain the Trinity (the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost), the druids started to laugh at his attempts, which they believed to be ridiculous. Patrick, in his desperation, took a shamrock and told the audience: “There is one stem but there are three leaves on it. So it is with the Blessed Trinity. there is one God, but three persons stemming from the same divinity.” King Laoghaire allowed St. Patrick to spread the Gospel throughout Ireland, but he said he would refuse to accept Christianity for himself, as it would betray his ancestors, who entrusted him with the land and his tradition. St. Patrick was on his way and spread the gospel throughout Ireland. St. Patrick is also known for driving the snakes out of Ireland. We know as a fact that there never were snakes in Ireland. The Church explains that it was meant as a symbol, and that St. Patrick was driving out paganism. When St. Patrick reached the age of 50, he made a pilgrimage to Croagh Patrick. In his devotion, the devil tried to tempt him, but Patrick resisted. Patrick was rewarded by God, who send an angel to grant him a wish. He asked that the Irish should keep the Christian faith for all time and that they should be spared the horrors of judgment day. When that time came, Patrick could judge his beloved Irish himself. It is from this time that the legend arose that Ireland would be drowned under a sea of water seven years before the Last Day originates. In the year of 441 A.D., Patrick returned to Rome to pay homage to the new Pope, Leo I. He was given relics from Saints Peter and Paul which, on his return to Ireland, he placed in his new chapel at the Metropolitan See in Armagh. St. Patrick died on March 17th, in the (assumed) year of 461 A.D., at the age of 76. The clans of Ireland began to bicker over who should receive the honor of providing the final resting place. To avoid this sacrilegious end to his life, his friends secreted his body away to bury it in a secret grave. Many believe this to be in Down Patrick, County Down. BASIC RETREAT RULES

1. The pilgrimage season begins each year on June 1st and ends on August 15th.

2. Pilgrims may begin their pilgrimage on any day of the season until August 13th inclustve. 3. No advance booking is necessary. 4. Pilgrims must arrive at the lake shore before 3.00 p.m. 5. They must have fasted from all food and drink (plain water excepted) from the midnight prior to arrival. 6. They must be over 14 years of age. 7. Only pilgrims are admitted to the island during the pilgrimage season. 8. On performing the spiritual exercises of the pilgrimage, pilgrims are granted a Plenary Indulgence applicable to the souls in Purgatory. 9. Information may be had at any time by writing to the Prior. THE PILGRIMS

Women pilgrims exceeded men in 1977 by 7 to 2; pilgrim priests numbered 190, of whom one was a bishop. In recent years religious sisters have come in greater numbers. The majority of pilgrims still come from the northern half of the country, but with more buses and cars on the road nowadays one hears more and more the softer accents of Munster and South Leinster. Dublin and Belfast are well represented, especially at weekends.

There are always pilgrims from overseas on an Irish holiday, most of them of Irish parentage or origin. A number of English and Scottish pilgrims make the very considerable financial sacrifice of coming specially to Ireland to make the Lough Derg pilgrimage. Many pilgrims too, follow a long family tradition. Many come annually or once every two, or three years. Priests often bring parish groups with them and there are several pilgrimages organized every year by church organizations like the Legion of Mary. |

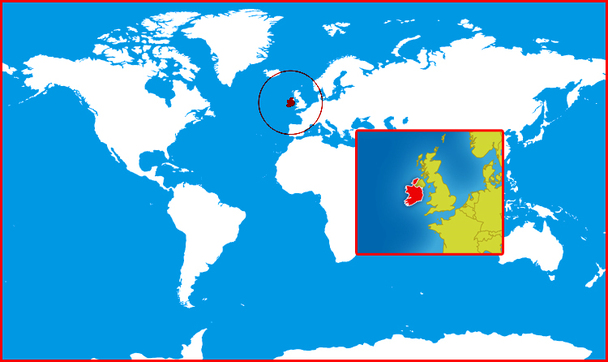

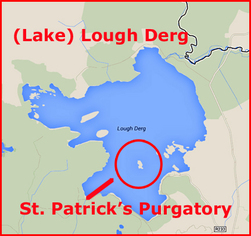

WHERE ON EARTH IS ST. PATRICK'S PURGATORY?

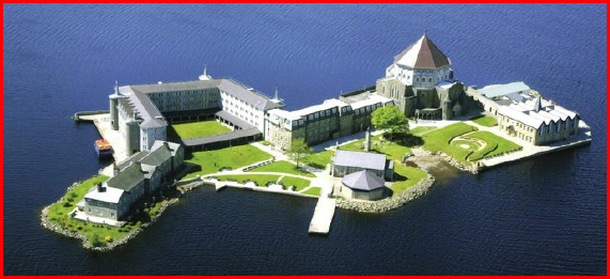

Lough Derg, Ireland. This celebrated sanctuary in Donegal, in the Diocese of Clogher, dates from the days of St. Patrick, but it is also known as the Lough Derg pilgrimage, so named from Lough Derg, a sheet of water, measuring 6 miles by 4 miles and covering 2200 acres, with a circumference of about thirteen miles, and standing 450 feet above sea level, on which are eleven islands, the principal of which are Saints Island and Station Island.

The sanctuary lands on Saint Island were known in the Middle Ages as Termon Dabheoc (from the sixth-century St. Dabheoc who presided over the retreat), and were subsequently called Termon Magrath from the family of Magrath, who were coarbs or stewards of the place from 1290. St. Patrick’s connection with the purgatory which bears his name is not only a constant tradition, but is supported by historical evidence, and admitted by the Bollandists. Like many of the sites of the old Irish monasteries, the natural surroundings of Lough Derg capture the unspoiled peace of the place. The lake is extensive, six miles by four, and is surrounded on all sides by low heather-clad mountains which have been partly forested in recent years. Only one good road leads to the lake, from thesmall town of Pettigo, four miles away on the Donegal—Fermanagh border. This road brings all pilgrims to St. Patrick’s Purgatory and ends at the ferry where there is a house and offices. The pilgrim looks around him in vain for any other sign of dwelling or cultivation. But he sees at once from the lake shore the many clustered buildings of the island purgatory, dominated by the green dome of the main church. It is to this island, called Station Island, the pilgrim comes as the many thousands have come since the days of St. Patrick. The peace of the natural surroundings is caretully preserved on the island. There is no commercialisation of any kind. No tourists or sightseers are permitted during the pilgrimage season; pilgrims may not bring cameras, radios or musical instruments. The only concession to commerce is a small unobtrusive shop where the pilgrim gets the leaflet of instructions and where Rosary beads, prayer books, postcards and cigarettes are on sale. The privacy of the pilgrim is respected at all costs and he may remain anonymous and observe silence if he wishes. There are no community exercises apart from those of prayer. In general, the pilgrim is encouraged to absorb the pervasive calm of the island in his mind and heart in order that he may with greater ease make his peace with God. The buildings on the island harmonize with this atmosphere. Two churches and two hospices form an enclosure for the penitential cells, traditionally called “beds”. The buildings belong to different periods over the last hundred years while the beds are remnants of an ancient monastery.

As the pilgrim walks up the island from the boat-quay he passes the beds on his right and approaches the larger church which he has already seen from the mainland shore. Built over the edge of the island with local stone, its robust design takes full account of the expansive and simple setting of lake and mountain. The eight-sided shape of the interior makes community worship as intimate as possible in a church which seats 1,200 people. This church, dedicated to St. Patrick, was consecrated in 1931 and was then the only church in Ireland with the title of Basilica. The original design was by Professor W. A. Scott and the stained-glass windows depicting Our Lady, St. Paul and the Twelve Apostles, each carrying one of the Stations of the Cross, were the work of the Dublin artist, Harry Clarke. Less obvious artistic details in the Basilica are the symbols of the four evangelists inset in colorful mosaic in the pillars of the altar rails and the coat of arms of Pope Pius Xl over the main entrance doors.

Every day during the pilgrimage season the stillness of the island is broken by the gentle sound of an open-air bell in a stone tower above the beds. This bell-tower is built on the site of the original cave where pilgrims formerly kept vigil and which gave the name “purgatory” to the island. About 1780 the cave was finally closed and replaced by a church on the site of the present Basilica called the “prison chapel”. The ritual closing of the huge Basilica doors at the beginning of the vigil every night preserves this idea of being imprisoned for a time in Purgatory and of awaiting with Christ the dawn of the Resurrection.

Our Lady, the greatest of all the saints, is also honored on Lough Derg. St. Mary’s Chapel was originally built by the Franciscan Father, Anthony O’Doherty, in 1763 and was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Angels. The present building dates from 1870 and was greatly enlarged with new confessionals in 1976. Special features of St. Mary’s are a glass reliquary and a mounted ‘penal’ crucifix which was found in the hands of one of the victims of the drowning tragedy of 1795. BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SHRINE

St. Patrick’s Purgatory, located on what is called Station Island on Lough Derg (Lake Derg), was the principal landmark on

the medieval maps of Ireland. It was, for example, the only Irish site named on

a world map of 1492. We know, from the multitude of written literature of the

period, that many distinguished pilgrims from all parts of Europe — France,

Hungary, Spain, England and Holland — came to Lough Derg from the twelfth to

the fifteenth centuries. But the vast majority of pilgrims in these years, as

always, were Irish men and women.

A monastery probably existed on the islands in Lough Derg from the fifth century and it probably included anchorites who lived in beehive cells – which may be preserved in some form in the penitential beds that can still be seen on Station Island. Around 1130 the monastery was given to Augustinian Canons Regular by the authority of the cathedral in Armagh, under Saint Malachy. The monastery on nearby Saints Island offered hospitality to pilgrims, who would visit in a spirit of penance and prayer. It also served as a place where pilgrims could prepare themselves for visiting St. Patrick's Purgatory on the neighboring Station Island. Documents report that pilgrims who wanted to visit the St. Patrick's Purgatory would arrive with letters of permission from a bishop, either from their own region, or from the nearby see of Armagh. They would then spend fifteen days fasting and praying to prepare themselves for the visit to Station Island, a short boat ride away. At the end of the fifteen days, pilgrims would confess their sins, receive communion and undergo a few final rituals before being locked in the cave for twenty-four hours. The next morning the prior would open the door, and if the pilgrim were found alive, he would be brought back to Saints Island for another fifteen days of prayer and fasting. From the time of St. Dabheoc (sixth century), it appears that this region attracted pilgrims from far and wide. By the twelfth century they came from all over continental Europe, most likely sailing from England and landing at Dublin or Drogheda. From those ports they would make their way by foot, stopping at monasteries along the way on what would probably be a two-week journey across the Irish countryside to their destination. In this period many sinners and criminals were sent on pilgrimage to atone for their deeds and seek forgiveness. St. Patrick’s Purgatory would be a likely destination for these penitential pilgrims, or exiles, since communities of anchorites were often considered to have special power to absolve them. In 1470, Thomas, Abbot of Armagh, got the priory in commendam, and in 1479 the community had almost died out, the revenues being farmed by Neill Magrath. Pope Alexander VI ordered the cave to be closed on Saints Island, the papal decree was executed on St. Patrick’s Day, 1497. A few years later, in 1502, the station was transferred to Station Island, where the Purgatory had originally existed. The cave was visited by a French knight in 1516, and by the papal nuncio, Chiericati, in 1517. Though formally suppressed by the English Government in 1632, the lay owner permitted the Austin Canons to resume their old priory, and in 1660 we find Rev. Dr. O’Clery as prior, whose successor was Father Art Maccullen (1672-1710). The Franciscan Friars were given charge of the Purgatory in 1710, but did not acquire a permanent residence on the Island till 1763, at which date they built a friary and an oratory dedicated to St. Mary of the Angels. In 1780 St. Patrick’s Church was built, and was subsequently remodeled. From 1785 the priory has been governed by secular priests appointed by the Bishop of Clogher. In 1813 St. Mary’s Church was rebuilt, but it was replaced by the present Gothic edifice in 1870, and a substantial hospice was opened in 1882. The number of pilgrims from 1871 to 1911 has been about 3000 annually, and the station season lasts from June to 15 August. The station or pilgrimage lasts three days, and the penitential exercises, though not so severe as in the days of faith, are austere in a high degree, and are productive of lasting spiritual blessings. By 1710 the Franciscans were present on the island in the summer to administer to the needs of the pilgrims. They built a church, St. Mary of the Angels, on Station Island in 1763. In 1785, administration of Station Island came into the hands of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Clogher. THE CAVE UNDER THE BELL TOWER

It is said that Jesus showed St. Patrick a cave on Station Island (sometimes described as a “pit” or “well”, of which there are a few shallow ones remaining), in which the saint received visions of the punishments of Hell. It was described by pilgrims of the time as a small pit or cave, the floor of which was reached by about six steps. Most of it was only high enough to kneel in. After many days of fasting and spiritual preparation, pilgrims could opt for spending time locked in the cave for twenty-four hours. It is said that, during those twenty-four hours of being locked in the cave, many saw the torments of Hell or Purgatory that awaited them if they did not repent of their sins.

Every day during the pilgrimage season the stillness of the island is broken by the gentle sound of an open-air bell in a stone tower above the penitential beds. This bell-tower is built on the site of the original cave where pilgrims formerly kept vigil and which gave the name “Purgatory” to the island. About 1780 the cave was finally closed and replaced by a church on the site of the present Basilica called the “prison chapel”. The ritual closing of the huge Basilica doors at the beginning of the vigil every night preserves this idea of being imprisoned for a time in Purgatory and of awaiting with Christ the dawn of the Resurrection.

PROGRAM OF PRAYER AND PENANCE

Pilgrims arrive on the island any time before 3.00 p.m., having fasted from midnight from all food and drink except plain water. The leaflet which is always available at the shop beside the pier gives full details of the fasting regulations and of the timetable. The pilgrim then goes to the hospice and takes off all footwear before beginning the first station.

At 10.15 p.m. pilgrims assemble in the Basilica to begin their vigil. They will not be allowed to sleep at all on this their first night of the retreat. The vigil means keeping awake for twenty-four consecutive hours and is by far the most difficult part of the ascetic program. It begins with a holy hour of preparation in common for Confession followed after an interval by the Rosary, both of which invite reflection and mental prayer. Four stations are recited in common in the Basilica during the night, with intervals between the stations for taking fresh air and relaxing outside or in the night shelter. Pilgrims walk around the interior of the Basilica during the stations, as much as the numbers permit. Gradually the long night melts into dawn and all pilgrims re-unite for Morning Prayer and Mass.Morning Prayer and Mass, Confession, Stations of the Cross, Evening Mass, Night Prayer and Benediction complete the timetable of spiritual exercises. The pilgrim makes a station outside on the second day and one on the third day before leaving. He goes to bed on the island on the second night but keeps the fasting regulations until the end of the third day.

During his stay here the pilgrim is surrounded by symbols from the Bible and the Liturgy. The three-day retreat from the world is a sharing in the paschal mystery of Christ who died to the world and rose again on the third day. The crossing by water is a reminder of the Baptism ceremony which is the beginning of the Christian life. Bare feet for Moses and Joshua in the Old Testament were a sign of reverence and respect for the presence of God. The gathering of pilgrims for Mass is a real experience of belonging to the Church through which we work out our salvation. When we renounce the World, the Flesh and the Devil with outstretched arms, we have the Church at our back, morally as well as physically. The shared fast and vigil bind pilgrims together and unite them with suffering souls in Purgatory and throughout the world. The over-all program leads pilgrims to participate more fully in the sacraments of Penance and the Eucharist. By prayer and penance we imitate Jesus who prepared himself for his total giving to the Father by his ascetic life. In the sacrament of Penance we acknowledge the Father’s welcome and accept again the privileges of sonship. At Mass we take our place with our brothers at the table of Christ’s sacrifice. The whole process is one of conversion, renewed and continuing conversion from self to God through Jesus Christ Our Lord. THE "PENITENTIAL BEDS"

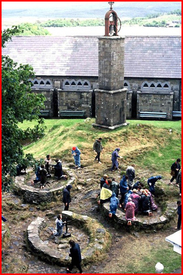

The ‘Penitential Beds’ are one of the most prominent features associated with the Lough Derg pilgrimage. The seven Penitential Beds – small low circular walled structures – are the remnants of monastic beehive huts. The Penitential Beds on Station Island belong to the Celtic monastic period. They were reconstructed remains of monastic cells or oratories where monks might spend time alone to pray. They are called “lecti poenosi”, or penitential beds, in the earliest records.

Today, what remains, are rings of boulders and rough stones embedded up-end in the soil, some on a steep incline and in the centre of each stands a crucifix. They form a central part of the Stations which pilgrims perform during their stay on the island. This post is a collage of images and texts which centre on the beds. At each of the beds, pilgrims walk barefoot three times around the outside; kneel at the entrance, walk the interior three times and kneel at the cross; during each of these they say three Our Fathers, three Hail Marys and one Creed. The penitential beds are dedicated to seven saints, each having some association with the area. A Franciscan Friar, Michael O’Cleary recounted that the pilgrimage was being performed in 1600- the earliest systematic account to survive. For the first time the prayers are detailed in this account as are the saints to whom the penitential beds are dedicated. St. Brigid: The first bed is dedicated to St. Brigid for there was a special devotion to St. Brigid in this part of Donegal. Another relic on the island is St. Brigid’s Cross, which is cut in a block of stone and inset in the left-hand outer wall of the Basilica. The cross is of Roman type and probably dates from the 12th century. On the mainland, by the lakeshore there is Brigid’s Well and Brigid’s Chair. Adjacent to the Visitor Centre on the lakeshore, a small chapel, dedicated to St. Brigid, was built in 1995. St. Brendan: A native of Coonty Kerry, St. Brendan was renowned for his voyages. He was the founder of the monastery at Clonfert. St. Catherine: It is generally held that the Catherine to whom this bed is dedicated is St. Catherine of Alexandria, the patron saint of wheelwrights in the Middle Ages. St. Columba: Born in Gartan, County Donegal, St. Columba (or St. Columcille in the Irish language) founded many monasteries including Durrow and Derry. He spent most of his life on the island of Iona. St. Patrick: St. Patrick is reputed to have visited Lough Derg in 445 when he spent time there alone in prayer and penance. St. Davog: St. Davog is said to have been a disciple of St. Patrick and was the first Abbot of the monastery at Lough Derg. St. Molaise: St. Molaise was a local saint who died about 563. The earliest recorded mention of the seven saints of the beds occurs in an Irish poem from about 1590. SAINTS ISLAND

Saints Island may be easily seen from the rear of the Basilica. This was the center of the monastery which was founded in the time of St. Patrick and continued by the Canons Regular of St. Augustine, who came in the 1130’s. The Canons were here about fifteen years when they were visited by the Knight Owen, the man who made the cave on Lough Derg famous all over Europe. The cave at this time was, as always, on Station Island, but some time later a second cave for pilgrims to keep vigil was opened on Saints Island. This second cave was suppressed by Papal order in 1497 without interfering with the original.

Saints Island was originally called St. Davog’s Island, after the first abbot of the monastery. St. Davog is the local patron of Lough Derg and one of the beds on Station Island preserves his name. He is said to have been a disciple of St. Patrick and to have come from Wales. He is listed among the Twelve Apostles of Ireland in the legend that describes the cursing of Tara and his name was widely revered as late as the 13th century. A great boulder called St. Davog’s Chair on the top of one of the mountains near the ferry on the mainland, gives the best aerial view of Station Island. The pilgrim will note from the leaflet that Davog’s name on the bed is linked with another local saint, Malaise of Devenish. Malaise (pronounced mo-lash-eh) died about 563, outliving Davog by forty-seven years. It is said that his monastery on Devenish on neighbouring Lough Erne adopted the rule of Davog. |

Web Hosting by Just Host